Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

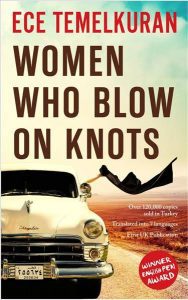

Index on Censorship contributor Ece Temelkuran’s latest novel is Women Who Blow on Knots.

Turkish author Ece Temelkuran is growing increasingly anxious about life under President Erdogan, she told Index on Censorship.

“After the failed coup attempt, the crackdown began on journalists, but we thought that writing fiction would provide a safe shelter,” she said. “Now we are seeing even the novelists are being targeted, and it makes you think there is no haven for anyone with critical thought.”

Asked whether her worries have begun to affect her own work, she paused before adding: “There is no justice in Turkey as we know it in the West. We don’t know what tweet, what thing you write could be the thing that puts you under the spotlight. The unhappiness in Turkey is so big, so palpable that you can touch it. It paralyses the human mind. Turkey does not let you do any intellectual work.”

However, Temelkuran, speaking to Index in London at an event to promote her new book The Women Who Blow on Knots, insisted that she would never allow Erdogan to force her to flee her homeland.

“The idea of leaving Turkey permanently is horrible because it deprives you of home, which I believe is inhumane. The supporters of Erdogan are constantly claiming that they are the ‘real people’ of Turkey, and I feel we have to constantly remind them that we are also real people.”

With the country heading down an authoritarian path following Erdogan’s success in a recent referendum that granted him vast new powers, Temelkuran believes Turkey faces a long road back. “It’s not easy to be hopeful, but one can be easily inspired by the people who are resisting,” she said, giving the example of two educators, Nuriye Gulmen and Semih Ozakca, who went on hunger strike in March 2017 in protest at losing their public sector jobs in the post-coup purge. Soon after Temelkuran’s interview, the pair were arrested and charged with membership of a terrorist organisation. They vowed to continue striking in prison.

The Women Who Blow on Knots tells the story of a group of women travelling through the Middle East during 2011’s Arab Spring. In conversation with author Diana Darke, Temelkuran explained that the title of her book is a reference to a passage from the Koran warning of the evil of women who performed witchcraft by blowing onto knotted rope, inverting the idea into an acknowledgement of female power.

“If our breath is so strong why not use it,” she said. “The main idea is that women blow life into things, into men, into children, into anything. They create life.”

The novelist also referred to one scene in which a group of Libyan militia women are watching Sex and the City, saying that she believes cultural divisions are overrated. “We’re watching the same TV series, using the same brands, reading the same books, we are watching the same Trump, whatever. The world is not completely like one village, but the cultural references are getting more and more common.”

However, in the context of a divided Turkey, she said that “it is as if there is this soundproof wall” in the middle of the country, with neither east nor west caring to learn about life on the other side. “This is something that I learned in early ages – the ones who stand in the middle get shot by both sides.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1496743531699-19a91ff0-06b4-6″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

It took me three tries to watch the video, which has since been removed from YouTube by the user. The first pass was simply because it was one of the most popular videos during the latest war of words Europe-Turkey crisis. On the second pass, I got over my initial disgust and watched it fully. The third pass allowed me to step back and think about the question of how its creator is part of a social phenomenon.

In the video, a Turkish man of about 25 or so with an Islamic beard is phoning the Dutch police while proudly telling the viewer what he is up to with a wicked smile. As soon as the call is answered, he begins speaking in Turkish while in the background a friend blares an Ottoman war march from another smartphone. He tells the police: “Get your grannies ready! Because our grandfathers are coming for them!” He does not use the F word. He doesn’t need to. His obscene smile makes that clear.

This man is a fellow citizen of Turkey. As an educated Turk, I am supposed to understand him, even respect him and his point of view. Otherwise I would be categorised as part of the “oppressive, arrogant elite”. He, on the other hand, has no such responsibility. He just is. He’s free to carry on in his chauvinist bubble secure in the righteousness of his cause.

Soon the world might be full of such men and women, who are proud to be vulgar and carrying unleashed banality as a political identity. All over the globe, these individuals claim to be “real people”. If they are the “real”, then anyone who is astonished by their inane antics of this reality show is “unreal”.

Unfortunately, these “real people” like the men in the video have been the social and psychological stronghold of Turkey’s government and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. They are also the leading actors in the Europe-Turkey crisis playing out on the streets of the continent’s cities. They have become internationally visible due to the demonstrations in The Netherlands and elsewhere. A European citizen who sees such videos and such people may think that these “real people” represent all Turks. They do not.

As a matter of fact, these people simply were not. They did not exist. They were manufactured during the AKP’s time in power. It is as if the concept of shame has been removed from the social lexicon. This loosening of morals has allowed these individuals to become the dominant figures and even role models in society. As the AKP and Erdogan evolved to become borderless, so did their followers.

When the AKP was vying to come to power in 2002, I went on an election tour to meet this new brand of conservative. It was a new social movement — a movement of the righteous, if you will — being born before our eyes. I met local representatives of the party who were usually the most respected figures in their town or neighbourhood. Each of them was exceedingly polite, presentable and moderate in their conservative lifestyle. Although the conventional wisdom had it that these new kids on the block couldn’t possibly pull off an election win, some of us were aware that there was something new in the air and that the political scene would never be the same. Abdullah Gül, an AKP founder and former president was the balanced and well-educated figure who described this young force by saying: “We are the WASPs of Turkey.”

And then it happened. The AKP wasp won the election in a landslide. In my column written after Erdogan’s first, unexpected victory, I wrote:

“Erdogan somehow magically made himself be seen as the underdog and managed to identify himself with the masses. Throughout the election period, he made himself look like he was never allowed to speak by the old guards of the secular regime, which made the voters suffer for and with him. Now he is the winner and we will see for how long he will be able to sustain the role of ‘the sole oppressed’. And we also will have to think what the political answer could be to this spectacle of the fabricated oppressed.”

The column was printed in November 2002. Since then Turkey’s political opposition has struggled to formulate a response to Erdogan’s “underdog politics”. Now he’s playing it on an international stage with much higher stakes.

So if Europeans or Americans are wondering whether or not the argument of the “oppressed and neglected real people are coming to power” farce is sustainable, the answer is it sustained in Turkey for 15 years and still there is no light at the end of the tunnel. For the last fifteen years rebranding the lumpenproletariat as “the real people” in Turkey first legitimised, then exhilarated and finally sanctified all the eccentricities, banality and the ultimate vulgar and now all Europe is watching the spectacle of this fabricated mass. Meanwhile Erdogan, who still is “the man who is not allowed to speak”, is giving endless speeches about how he and his people are silenced.

During the first half of these 15 years, one of the most popular stories circulating on Facebook was about that old cliché: boiling the frog slowly. Before the Turkish and Kurdish opposition were deep fried in prison cells, Erdogan was excelling in making different and sometimes opposite sectors of the social and political spectrum believe that he was actually their man in Ankara. The Kurds fell for it. The liberal democrats fell for it. Some feminists and some LGBT people did as well, not to mention the conservative nouveau riche and radical Islamists.

However, on the day that his second term began in 2007, he was already very clearly hinting at what he would do. In his victory speech on the election night, he said: “All those who did not vote for us are also the colours of this country.” Somehow many intellectuals saw this as an “all-embracing” speech. But I wasn’t. My article on that day infuriated many. From my point of view, Erdogan was making people like me “the embellishment on the plate that could be removed if not wanted”. Somehow, as with the USA today, the masses have a tendency to woolgathering, to think that things cannot be that bad even when the leaders make it crystal clear they actually will be. Yes, that wall could really happen. What’s worse, children could have teachers loyal to Trump’s doctrine, Americans could be glued to Trump TV and neighbours could turn on neighbours for disloyalty.

A country’s leadership sets the tone, but can also penetrate the very fabric of the public’s existence, igniting a metamorphosis that creates political clones. Power doesn’t just stun people but also hypnotises them into becoming little creatures at the command of the leader.

So now I am watching a video produced by my fellow citizen, a Frankenstein monster, who thinks that the idea of our Ottoman grandfathers raping European grandmothers is not only amusing but also a way to educate infidel Westerners. He was just about 10 when the AKP came to power. He grew up imbibing the belief that he could do anything if portrayed himself as the underdog. He thinks that educated people are evil because it has been drilled into his little mind by the political machine. He has been ruthlessly force-fed Turkey’s rewritten history, which is a bizarre combination of the greatness of our illustrious ancestors and how the secular elite paired with Westerners to steal Turkey’s greatness through devilish tricks. He believes that if one man rules the country all the confusion will be gone, Turkey will be great again and everything will be awesome.

Today I wonder what happened to those polite and proper AKP representatives I met in 2002. But more importantly what will happen to these newly fabricated people if — and when — Erdogan is gone? What will happen to these creatures after their creator has left the scene? Will some future leader be trolling through video channels to hunt them down?

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1489681834044-91157d11-36c9-7″ taxonomies=”55″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/LzWBgzJrQdo”][vc_column_text]As tens of thousands of women took to the streets around the world on 21 January, another woman, the Turkish MP Şafak Pavey was being treated in hospital for injuries sustained during a physical assault on the floor of the Grand National Assembly during debates on constitutional amendments.

Pavey had just delivered a moving speech in which she warned that the presidential system being considered would bring about unchallenged one-man rule. The “bandits”, as she called them, a group of women MPs belonging to the ruling AKP, attacked her and two other MPs, Aylin Nazlıaka, an independent, and Pervin Buldan from the Kurdish HDP. The AKP MPs were said to be acting under a male colleague’s orders.

The attack contrasted sharply with the pictures of enthusiastic women from around the United States and the world committed to sisterhood and equality. The distance between the two extremes might seem to be yawning but isn’t. In Turkey, the gap opened up in just four short years.

The empowered mood created by women marching for equal rights and uniting their voices in opposition reminded me of the heady days of 2013 when the anti-government Gezi Park protests rocked Turkey. Like the demonstrators in DC and London, people all over Turkey took to the streets to raise a chant against our own Trump: President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. In Gezi, the seeds of dissent spread through social media and bloomed across the country just as the women’s march did across the globe. It was just the beginning, or so we thought.

After a brutal suppression that left at least 10 dead and over 8,000 injured, the Gezi spirit, that united voice, faded away. The most significant political heritage was the “Vote and Beyond” organisation, which launched an incredibly effective election monitoring network during the June 2015 elections. Thanks to that group and the popular young Kurdish leader Selahattin Demirtaş’s energy, the outcome of the polls reflected the full and complete picture of Turkey’s population in parliament. The combined opposition parties were the majority in the assembly and to continue governing, the AKP would be forced to form a coalition. Then things happened.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”85130″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]As the ceasefire with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) collapsed and armed conflict resumed, coalition negotiations ground into political deadlock as the summer wore on. Erdogan called a snap election for that November that lined up with his political ambitions. Less than a month before the election, a staggering terror attack rocked Ankara and ongoing deaths of security personnel in the country’s south-east added to a grim mood. At the polls, the AKP regained its majority in parliament. Though the governing party was nominally back in full control, it lacked political legitimacy and popular support, both of which would be delivered by the rogue military units that staged the failed July 15 coup and paved the way for Erdogan’s emergency rule.

Witch hunts are a strange thing. Even if you spot one when it’s getting underway, it’s always too late to stop it.

After the election, the political opposition was locked out of enacting change through parliament. It was further paralysed by Erdogan’s “shock and awe” tactics, which saw the leaders of the parties assaulted on the floor of the assembly or imprisoned on fabricated terror charges. Opposition voters are too depressed now to remember the confident and exhilarating days of the Gezi protests.

It would be a mistake to dismiss Turkey’s experience as a unique case. There are parallels with the unfolding situations in Russia, Poland, Hungary and now the USA. The bullies of our interesting times are singing from the same hymn sheet, using identical language and narratives — power to the right people, experts and intellectuals are overrated, overturn the establishment. The forces of resistance must now share strategies as well. Opposition to the growing threat of illiberal democracy needs to network and be vocal or else our initial responses to the horrors and human rights violations — including the purge of Turkey’s press under emergency rule — would be a waste of time.

Here’s a small taste of where we failed in Turkey — a warning to Europeans and Americans of what not to do.

“No” is an intoxicating word that gives emotional fuel to the masses. After swimming in the slack waters of identity politics or concerning yourself with whether or not your avocados are fair trade, taking to the streets en masse for a proper cause is like a fresh breeze. But as we learned in Turkey, “No” can also be a dead end. It exists in a dangerous dependency on the what those in power are up to. It shouldn’t be mistaken for action as it is only a reaction.

“No” is unable to create a new political choice. It is an anger game that sooner or later will exhaust all opposition by splitting itself into innumerable causes intent on becoming an individual obstacle to the ruling power.

Make no mistake: the bullies of the world are united in a truly global movement. It is sweeping all before it. And it’s not just Putin, Trump, Erdogan or even Orban, it’s their minions, millions of fabricated apparatchiks that invade the political, social and digital spheres like multiplying gremlins.

What the opposition must do — what Turkey’s protesters failed to do — is strengthen the infrastructure, harden networks and open strong lines of communication between disparate groups whether at home or abroad. All those lefty student movements, marginalised progressive newspapers or resisting communities that are labelled as naïve or passé until now must coalesce around core campaigns and goals.

Failure to move beyond “No”, in Turkey’s case, has made alternative and potential political movements all but invisible. There are just three leftist newspapers in Turkey, three ghosts to break news about women MPs being beaten up. And that’s because we can’t move past “No” when others were shut down or silenced.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1485771885900-d32a2643-5934-8″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

This is the second instalment of Ece Temelkuran’s periodic diary of developments in Turkey’s age of emergency rule.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]23 November: The women around me are more alert to the Turkey’s situation than the men are. The comfortable male universe is full of denial encased in a constantly refreshed argument: “It cannot go on like this; this is not sustainable.” And my reiterated response to this denial: “What will stop it?” There are neither domestic nor international limits to the resident’s ambitions. While the world is rightly horrified by the jailing of writers and journalists, the objections fall on the president’s deaf ears. Turkey’s opposition is spent, its strength consumed by endless court appearances. A handful of lawyers are trying to catch their breath while running between courtrooms to represent or witness the trials of Turks caught up in the witch hunt that swept the nation in the wake of the failed 15 July coup.

24 November: Just another day in a land of insanity. The EU Parliament announced its decision to freeze Turkey’s accession talks due to the government’s suppression. Three soldiers were killed by a Syrian jet, interestingly on the anniversary of Turkish jets bringing down a Russian plane last year. There was no news due to the traditional news ban so we don’t know if there will be a war tomorrow. And Ahmet Türk, the most prominent and dovish figure of Kurdish politics was jailed. He is 74 years old. Turkish lira dipped to a new record.

On the streets, the humour is in accordance with the insanity: “Make Turkey so-so again!”

25 November: Castro dies. As with everything else, this also becomes a subject of dispute between opposition and government supporters. Nothing can escape being the object of polarisation in the country. After some people say goodbye to Castro on social media, government supporters revolt: “How can you support a dictator?” If the partisanship can make you defend child rapists, which happened recently due to a child abuse case in a government-affiliated charity foundation, it can make you do anything.

25 November: Castro dies. As with everything else, this also becomes a subject of dispute between opposition and government supporters. Nothing can escape being the object of polarisation in the country. After some people say goodbye to Castro on social media, government supporters revolt: “How can you support a dictator?” If the partisanship can make you defend child rapists, which happened recently due to a child abuse case in a government-affiliated charity foundation, it can make you do anything.

26 November: President Erdogan is threatening the European Union. “We will open the borders for refugees and you will see,” he says. His reckless statements are on one side, Europe’s ethical failure about refugees on the other. Erdogan now seems to be the bull abducting Europa. As the fundamentals of Western civilisation and democratic values come to pieces, the bulls around the globe find their way to the top.

One perfect Balkan noir scene at a Zagreb cafe. At each table there is a grumpy old man reading a newspaper while the young waiter plays high volume Riders on the Storm at high volume. He asks where I am from. “Oh Istanbul! Never been there,” he says. I smile. “Go before it is too late.” He smiles back with sarcasm: “I am from Bosnia. Everywhere is too late.” Maybe true. Maybe it’s a bulls’ world now.

27 November: I was avoiding this piece of news for two days. I have finally read it. A nine-year-old girl died of a heart attack because she couldn’t take the pressure of facing her rapist during her hearing in court. One friend asked: “Why have the men all of sudden became so evil in this country?” My answer is “Because they can!” When the rule of law is damaged and basic human values are shaken, they can. And we, stunned like a beaten dog, just murmur: “It cannot go on like this.” But it does.

28 November: Came to Copenhagen for NewXChange, the meeting point for the world of journalism. I will be speaking in a panel with the title Are we out of Touch? Well, Trump is tweeting: “CNN is so embarrassed by their total (100%) support of Hillary Clinton, and yet her loss in a landslide, they won’t know what to do.” He knows that attacking established media will get him more points than anyone can imagine. While talking about Operation Euphrates Shield president Erdogan said: “We entered Syria for nothing else but to end cruel reign of Al-Assad” It is as if Turkey declared war on Syria. People are asking, “How can he say that?” Well, shall I repeat it once more? Because he can.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1485774671069-2b48111f-e2eb-10″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]