Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”107951″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]“One of the things that motivated me to come forward was to…see the gap, the distance between what the public understood the laws…to mean…and also what our capabilities were, and how those were being applied,” Edward Snowden said.

Snowden was giving the keynote speech of Open Rights Group’s OrgCon 2019 on 13 July 2019, and he was at pains to emphasise to his listeners the importance of public understanding and awareness of the limits on digital freedom and privacy. “People think of 2013 as a surveillance story, but it was really a democracy story.”

Proponents of increasing democratic accountability would be pleased to see Snowden’s words reaching the public. The Open Rights Group reported a record-setting seven hundred or more attendees. Equally impressive were the number and quality of discussions and workshops available, all with the overarching purpose of educating participants about violations of privacy rights online. The Secret Life of Your Data workshops, for example, traced personal data from its collection on personal devices to the edges of the internet ecosystem, and a discussion of Dragonfly outlined the implications of allowing Google to create a censored search engine for China.

As participants in these workshops and presentations explored data exchanges and databases of trackers, they wanted to know what they could do to protect themselves. Here OrgCon’s offerings, united by their focus and thoughtfulness, began to diverge. Services like the Crypto Bar, which cheerfully urged attendees to “reclaim your rights online!”, coexisted uneasily with presentations illustrating the power and pervasiveness of the system opposing any individual wishing to do so. In the main lecture hall, a panel discussed the reality of facial recognition in the UK, while another space advertised an exploration of government power over children in “A Safeguarding Dystopia”.

Snowden was aware of the tension inherent in such seeming contradictions. However, he was convinced that a committed group of individuals could resolve it. During the Q&A period, he was asked by an audience member what hope there could be of securing data privacy and internet freedoms when the internet’s younger users were apathetic about both. He replied that understanding your rights online is difficult and time-consuming, so the goal of activists cannot be a universal understanding of the system which deprives internet users of their rights. Instead, it must be a new system which will protect those rights, even for the uninformed. For OrgCon’s attendees, informed by the day’s excellent events, leading the way to such a system might be the best self-protection.[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1563194731392-5cbccecb-ae6e-6″ taxonomies=”4883″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Although the USA is considered to have relatively generous freedoms of speech and the press protected under the First Amendment to the US Constitution, these freedoms have their limits. Many whistleblowers are not afforded protection in the USA and are subjected to lengthy prison terms after disclosing classified information to the public.

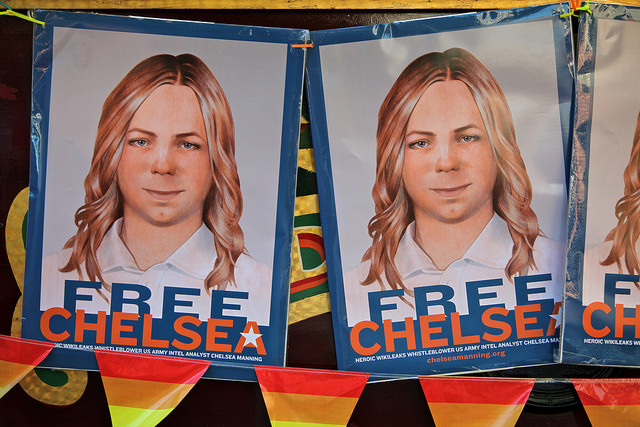

Chelsea Manning’s suicide attempt on 5 July, six years into her 35-year sentence, highlights the severity the USA practices when sentencing whistleblowers. Manning was responsible for the leaks of classified US military information to Wikileaks including videos, incident reports from the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, information on detainees at Guantanamo and thousands of Department of State cables. She was sentenced on 21 August 2013 to 35 years at the maximum-security US Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth.

Manning’s case appears to be the rule, not the exception, in the USA.

Jeffrey Sterling

Considered to be a whistleblower by some, Jeffrey Sterling, who worked for the CIA from 1993 to 2002, was charged under the Espionage Act with mishandling national defense information in 2010. Sterling was sentenced to three and a half years in prison for his contributions to New York Times journalist James Risen’s book, State of War: The Secret History of the CIA and the Bush Administration, which detailed the failed CIA Operation Merlin that may have inadvertently aided the Iranian nuclear weapons program. Risen was subpoenaed twice to testify in the case United States v Sterling but refused, resulting in a seven-year legal battle.

On 11 May 2015, at Sterling’s sentencing, judge Leonie Brinkema stated that although she was moved by his professional history, she wanted to send a message to other whistleblowers of the “price to be paid” when revealing government secrets.

Stephen Jin-Woo Kim

Stephen Kim is a former US Department of State contractor who, on 11 June 2009, spoke to Fox News reporter James Rosen about North Korean plans for a nuclear bomb test. Kim allegedly sought Rosen out after becoming frustrated that there was little being done in the Department of State in response to the threats of nuclear tests in North Korea, tests that were ultimately carried out. Fox News published Rosen’s article, North Korea Intends to Match U.N. Resolution With New Nuclear Test, which resulted in an FBI investigation. Kim subsequently pleaded guilty to a single felony count of unauthorised disclosure of national defense information and was sentenced to 13 months in prison on 7 February 2014.

John Kiriakou

John Kiriakou, a former CIA officer, was charged with disclosing information to journalists on several occasions, including revealing the use of torture on Abu Zubaydah and connecting a covert operative to a specific undercover operation. Kiriakou accepted a plea bargain that spared the journalists he had spoken with from having to testify by pleading guilty to one count of violating the Intelligence Identities Protection Act.

On 28 February 2013, Kiriakou began serving his 30-month sentence. He has stated that his case was more about punishment for exposing torture than leaking information and that he would “do it all over again”.

Edward Snowden

Although the most famous whistleblower on this list has not been tried and sentenced, Edward Snowden could face up to 30 years in prison for his multiple felony charges under the World War I-era Espionage Act. Snowden was charged on 14 June 2013 for his role in leaking classified information from the National Security Agency, notably a global surveillance initiative.

Snowden has expressed a willingness to go to prison for his actions but refuses to be used as a “deterrent to people trying to do the right thing in difficult situations” as so many whistleblowers often are.

Barrett Brown

The political climate in the US has become so hostile towards leaks that even journalists can face repercussions for their involvement with whistleblowers. American journalist and essayist Barrett Brown’s case became well-known after he was arrested for copying and pasting a hyperlink to millions of leaked emails from Stratfor, an American private intelligence company, from one chat room to another. The leak itself had been orchestrated by Jeremy Hammond, who is serving 10 years in prison for his participation, and did not involve Brown. Brown faced a sentence of up to 102 years in prison, once again for sharing a hyperlink, before the 12 counts of aggravated identity theft and trafficking in stolen data charges were dropped in 2013.

Although the dismissal of these charges was heralded as a victory for press freedom, Brown was still convicted of two counts of being an accessory after the fact and obstructing the execution of a search warrant. On 22 January 2015, Brown was sentenced to 63 months in prison and ordered to pay $890,250 in fines and restitution to Stratfor.

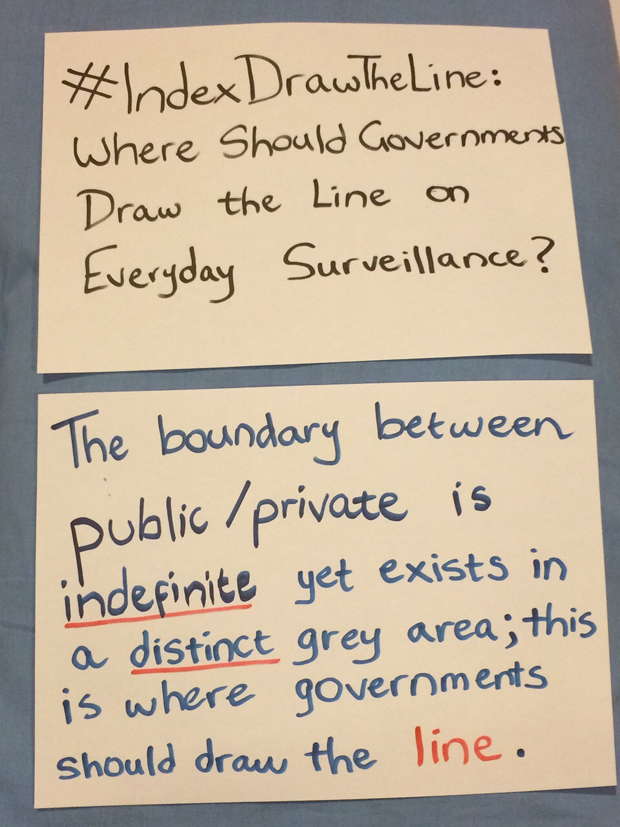

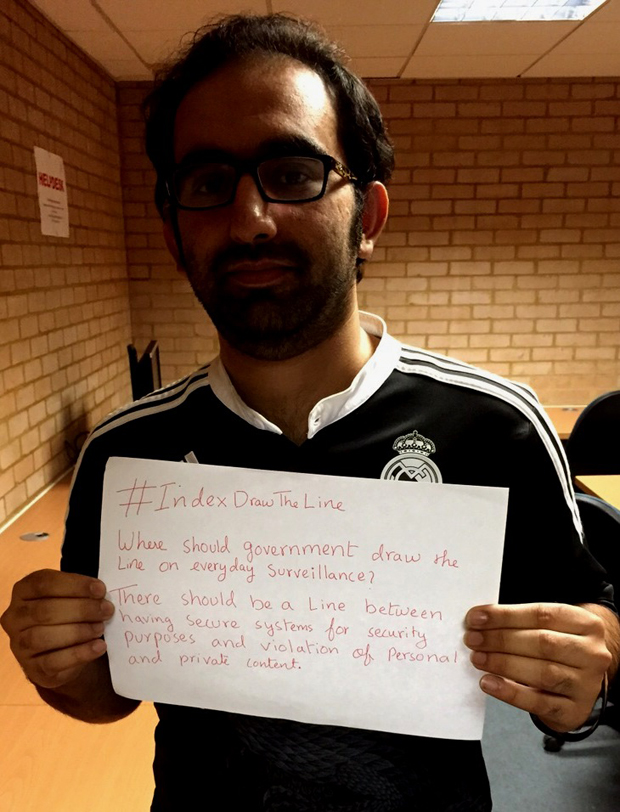

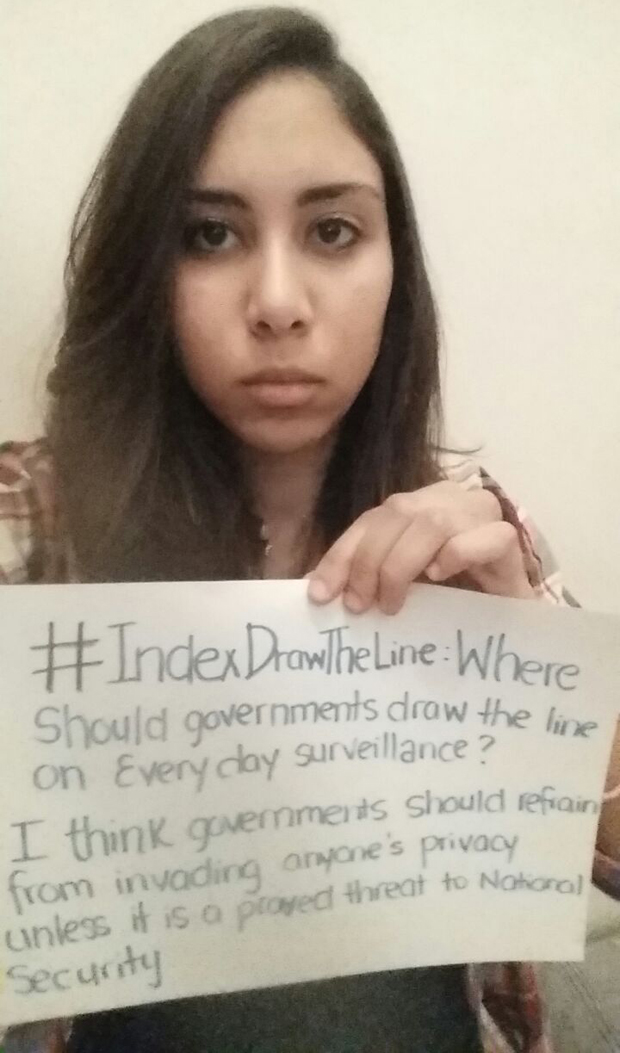

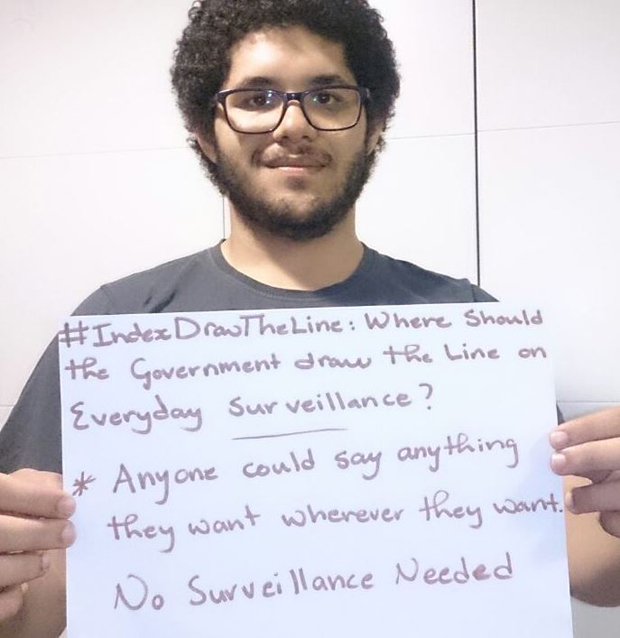

In the latest #IndexDrawtheLine, we’ve been asking the question: where should governments draw the line on everyday surveillance?

Mass surveillance has been a controversial issue, notably since former contractor for the US National Security Agency (NSA) Edward Snowden leaked information about the agency’s domestic spying. Today, some governments worldwide monitor phone calls, text messages and/or social media communications within the countries. Granted, mass surveillance may well be beneficial for governments to fight terrorism and ensure national security, but some people are concerned about the invasion of their privacy and personal life.

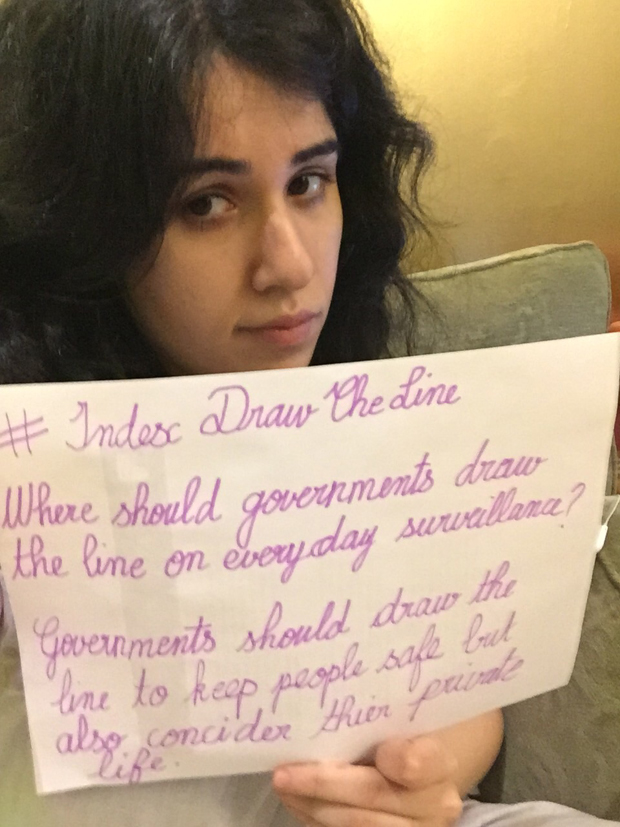

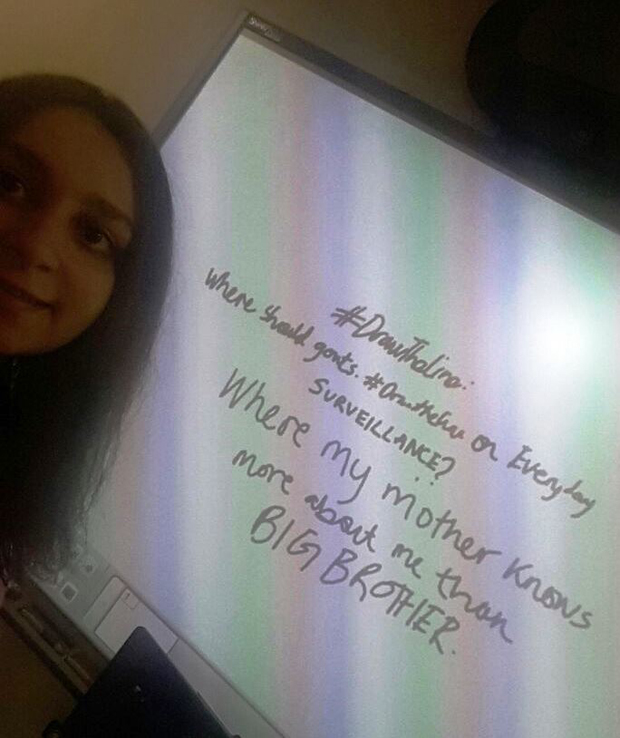

As well as the debate about this question on Twitter, we asked some students based around the world to give us their views. The students and their respective views can be seen in the form of photographs below.

One user on Twitter argued that the line should be drawn as per the law and added, “This right of OURS ‘…shall not be violated and no warrants shall issue but upon probable cause'” referring to the fourth amendment to the United States constitution.

Other responses suggested that governments should be able to ensure national security without invading the privacy of the people. One of the students below argues that the line should be drawn so that “my mother knows more about me than BIG BROTHER”, referring to the leader of the fictitious state from George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.

The general consensus seems to be that government surveillance should not happen unless it is proved there is a genuine threat to the safety and security of the people.

This article was posted on 6 June 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

Former NSA contractor Edward Snowden attempted to explain mass surveillance through a conversation around dick pics during an interview with John Oliver on Last Week Tonight, a satirical current affairs show aired by American network HBO.

“Even if you sent it to somebody within the United States, your wholly domestic communication between you and your wife can go from New York to London and back and get caught up in the database,” Snowden said in the interview, conducted in his temporary residence in Russia after the United States cancelled his passport for leaking details about NSA domestic spying in June 2013.

The elimination of complicated terminology in the discussion has allowed us to understand that although emails sent between Gmail accounts are encrypted and unidentifiable to outsiders as they move from Google’s data centres in the US and across the world, in reality the racy pictures embedded in these emails can actually be stored in several data centres worldwide as a way to provide backups in case one centre fails.

These encryption techniques have been around since 1991, when hacker Philip Zimmermann uploaded a free encryption program called Pretty Good Privacy – better known today as PGP – to the internet. Using a form of cryptography developed in the 1970s known as public-key cryptography, users are given a public key that can be shared which encrypts messages that are sent to them, and another one they keep private to decrypt messages they receive.

As public-key cryptography was generally reserved for military and government use prior to the release of PGP, the availability of these advanced encryption algorithms to the general public was a significant step in the realm of free expression at the time. But while web-based communication has become part of daily life, the average citizen is only beginning to grapple with the idea of mass surveillance let alone the tools associated with it.

Should individuals accept the surveillance environment, allowing – for example – government officials to obtain personal photographs shared between two consenting adults through a corporate service, as raised by Snowden?

Just months before Snowden blew the whistle, India began implementing a Centralised Monitoring System in April 2013 to monitor all phone and internet communications in the country. Following his disclosures on mass US secret surveillance programs, other governments around the world such as Brazil and Russia began debating on how to pressure companies to store user data locally. During this period, Turkey began drafting new regulations that would make it easier to get data from internet companies following the eruption of Gezi Park protests.

To what extent is it possible to escape everyday surveillance amidst these developments and how would this affect our communications? And even if technological advancement brings us newer tools providing stronger privacy protection, where should governments draw a line in monitoring what we share with friends and family?

Join the discussion on twitter with #IndexDrawTheLine