Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

David Miranda (Image: Elza Fiúza/Agência Brasil/Wikimedia Commons)

Index on Censorship today expressed disappointment at the High Court’s dismissal of David Miranda’s application for a judicial review of the use of anti-terror laws to detain him at Heathrow Airport.

“This ruling represents a dangerous elision of terrorist activity and legitimate journalistic practice,” said Kirsty Hughes, Chief Executive of Index on Censorship. “We must hope that it will not stand as precedent, as it could seriously endanger journalists working in the public interest.”

Mr Miranda, the spouse of journalist Glenn Greenwald, was stopped and searched under Schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act 2000 on 18 August 2013. He had been carrying encrypted files and documents originating from Edward Snowden’s leak of information on the National Security Agency’s mass surveillance programme.

A coalition of media and free speech organisations, including Index on Censorship, argued that it is inappropriate to use terror laws against someone such as Miranda, who was engaged in journalistic activity in transporting the documents intended to be used as source material for news stories in the public interest.

But the High Court today ruled that the use of the Terrorism Act did not infringe David Miranda’s right to free speech, or the rights of journalists to protect sources and materials. In his judgment, Lord Justice Laws ruled that the Schedule 7 detention of Miranda had been proportionate and did not “offend” his right to free speech under the European Convention on Human Rights.

This article was published on 19 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

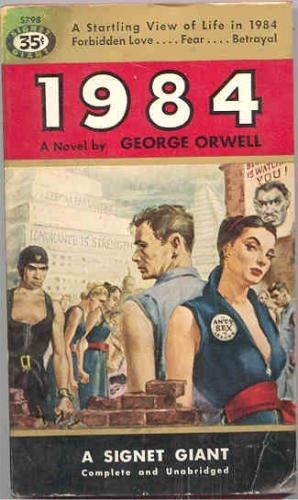

George Orwell died on this day in 1950. This article, from Index on Censorship magazine (volume 42,no 3), looks at one legacy he may not have liked.

Subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine here

The revelation that US intelligence services have allegedly been monitoring everyone in the entire world all the time was good news for the estate of George Orwell, who guard the long-dead author’s copyright jealously.

Sales of his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four rocketed in the United States in June as Americans sought to find out more about the references to phrases such as “Big Brother” and “Orwellian” that littered discussions of the National Security Agency’s PRISM programme.

The Wall Street Journal even went so far as to describe this profoundly bleak novel as “one of the hottest beach reads this summer”. And web editors, hankering after a top ten Google ranking for their articles, quickly commissioned articles on the Orwellian theme.

Meanwhile, news website Business Insider published a plot synopsis that managed to run through the events of the book without describing what the book was about at all. The nadir of this frenzy was reached by an Associated Press correspondent, who wrote of his “Orwellian” experience of being stuck airside at the same Moscow airport as whistleblower Edward Snowden for a few hours (for added awfulness, an editor’s note on the piece suggested that this deliberate exercise in boredom was “surreal”).

Nineteen Eighty-Four (not 1984) has become the one-stop reference for anyone wishing to make a point. CCTV? Orwellian. Smoking ban? Big Brother-style laws. At the height of the British Labour Party’s perceived authoritarianism while in government, web libertarians squealed that “Nineteen Eighty-Four was a warning, not a manual”.

It was neither. It’s a combination of two things: a satire on Stalinism, and an expression of Orwell’s feeling that world war was now set to be the normal state of affairs forever more.

A brief plot summary, just in case you haven’t taken the WSJ’s advice on this summer’s hot read: Nineteen Eighty-Four tells the story of an England ruled by the Party, which professes to follow Ingsoc (English Socialism). Winston Smith, a minor party member, thinks he can question the totalitarian party. He can’t, and is destroyed.

While Orwell was certainly not a pacifist, descriptions of the crushing terror of war, and the fear of war, run through much of his work. In 1944, writing about German V2 rockets in the Tribune, he notes: “[W]hat depresses me about these things is the way they set people off talking about the next war … But if you ask who will be fighting whom when this universally expected war breaks out, you get no clear answer. It is just war in the abstract.”

It’s hard for us to imagine now, but Orwell was writing in a world in which the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was not yet formulated, and where the Soviet Union seemed unstoppable. Orwell had long been sceptical of Soviet socialism, and for his publisher Frederic Warburg Nineteen Eighty-Four represented “a final breach between Orwell and Socialism, not the socialism of equality and human brotherhood which clearly Orwell no longer expects from socialist parties, but the socialism of Marxism and the managerial revolution”. Warburg speculated that the book would be worth “a cool million votes to the Conservative party”.

This is the context in which Nineteen Eighty-Four was written, and the context that should be remembered by anyone who reads it.

But too often it is imagined there is a “lesson” in Nineteen Eighty-Four as, drearily, it seems there must be a lesson in all books. There is not. The brutality of Stalinism was hardly a surprise to anyone by 1949. The surveillance, the spying, the censorship and manipulation of history were nothing new. Orwell was not so much warning that these things could happen as convinced that they would happen more. He offers no way out, no redemption for his characters. If this book were to have a lesson, Winston would prevail in his fight against the Party; or Winston would die in his struggle but inspire others. We would at least get far more detail on the rise of Ingsoc (the supposed secret book Winston is given, The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism, goes some way in explaining how the Party rules, but doesn’t really explain why it rules). As it is, we get an appendix on the development of “Newspeak”, the Party’s successful project to destroy language and, by extension, thought. This addition is designed only to assure us that the Ingsoc system still thrives long after Winston has knocked back his last joyless Victory gin.

There is no system in the world today, with the possible exception of North Korea (which has barely changed since it was founded just after Nineteen Eighty-Four was published), that can genuinely be said to be “Orwellian”. That is not to say that authoritarian states do not exist, or that electronic surveillance is not a problem. But to shout “Big Brother” at each moment the state intrudes on private life, or attempts to stifle free speech, is to rob the words, ideas and images created by Orwell of their true meaning – the very thing Orwell’s Ingsoc party sets out to do.

This article was posted on 21 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

(Photo: David von Blohn / Demotix)

German and British MPs last night called for NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden to be granted asylum in Germany.

Addressing a meeting called to support the Guardian newspaper in the face of threats from the British government, Conservative MP David Davis said that safeguards for whistleblowers were the only way to protect civilians from an overreaching surveillance and security apparatus, adding that “If whistleblowers can look forward to a life in Germany rather than a life in Moscow, I think that would improve things for everybody.”

German Green Party MP Konstantin Von Notz had earlier said that his country “needed to grant political asylum to Edward Snowden.”

The issue of surveillance has been hotly debated in Germany since it was revealed that the United States’ National Security Agency had been monitoring Chancellor Angela Merkel’s phone.

But speakers at the London meeting, convened by Observer and Vanity Fair journalist Henry Porter, expressed concern that a similar debate was not taking place in the United Kingdom.

Conservative MP Rory Stewart suggested that parliament’s intelligence and security committee should be openly elected and led by an opposition MP, thereby encouraging greater scrutiny of the security services’ actions.

“You are never going to have a government backbencher chairing a committee that is going to criticise the government properly,” said Stewart, a member of the Foreign Affairs Committee and a former diplomat.

Addressing Prime Minister David Cameron’s suggestion that measures would need to be taken to prevent the Guardian from publishing further revelations about surveillance by US and UK authorities, Davis said that no government in any other country where the stories had been published had attacked newspapers in the way the UK government had attacked the Guardian. He said “the only reason [the government] is doing this is out of embarrassment.”

The meeting, held at the Royal Institute for British Architects, heard from English PEN director Jo Glanville, who criticised David Cameron’s dismissal of civil liberties concerns about surveillance as “la-di-da” and “airy-fairy”. Davis echoed that sentiment, saying he delighted in being called “la-di-da” by old Etonian Cameron.

(Photo: David von Blohn / Demotix)

This article was originally published at Indy Voices

What’s happened to Edward Snowden and his revelations about the National Security Agency’s surveillance programme? As stories keep emerging from one of the largest leaks in US history, we learn more and more about the Americans’ ability to monitor communications, but seem less sure how to respond. Most people would acknowledge that the state does retain some right to monitor suspect activities. But this is a very different proposition from the population-wide mass surveillance suggested by the documents leaked by Snowden. Clearly the balance has tipped much too far in favour of default data gathering. So how do we move it back?

This is a complex discussion, and it’s not really being had in the UK right now. The Guardian’s Simon Jenkins has suggested an establishment conspiracy has kept the public from talking about this – it’s certainly true that the response here has not been on the level of that in other countries (not least in Brazil, where a national Internet redesign to avoid US surveillance is being considered).

But part of the problem here is not simply that people have been shielded from the discussion on surveillance, or that people don’t care. It is that people do not know what we are supposed to do about this. Who do we appeal to? What do we want?

This is where the European Union can come into its own. An Englishman’s home may be his castle, but nowhere is protection of privacy given more credence than in Brussels and Berlin. A horror of Soviet-style surveillance of citizens runs deep in many European institutions and nation states, particularly those that had hands-on experience. The most powerful person in Europe, Angela Merkel, remember, was a citizen of Stasiland.

The European Parliament’s Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs Committee (Libe), has set out to investigate claims of surveillance and examine what the EU can do about it. UK Labour MEP Claude Moraes has been charged with reporting on the Committee’s findings by the end of the year.

The parliament will be considerably aided by a 36-page briefing by independent surveillance researcher Caspar Bowden, who was helpfully mapped out the history of US and UK surveillance, and overlap with the European Union, all the way back to Alan Turing’s work with US spies in 1942.

Bowden comes up with several recommendations for Europe: the development of a “European cloud”, the revoking or renegotiation of mechanisms that allow US companies to gather data from European users, and, significantly in the case of the Snowden revelations, “systematic protection and incentives for whistleblowers”.

The European parliament investigation is welcome. But in reality, there is only a certain amount the parliament can actually achieve. The real power will, in the end, rest in the will of the governments of the respective European Union countries to act. Europe’s cyber strategy already states that “increased global connectivity should not be accompanied by censorship or mass surveillance”. But it’s time EU leaders acted on this.

That’s why Index on Censorship, along with dozens of other groups, including Amnesty, Reporters Without Borders and the Electronic Frontier Foundation, as well as stars and activists such as Bianca Jagger, Stephen Fry and Cory Doctorow, is petitioning European leaders directly. The next European Council Summit takes place at the end of October. We want every European government head there to publicly take a stand against mass surveillance.

The European Union, founded in part as a democratic bulwark against the authoritarianism of the eastern bloc, has a chance to stand out in the world against surveillance and for the rights of free speech and privacy. In the coming decades, power will be defined by who controls information: Europe, as a powerful democratic force, should work to ensure that its own ordinary citizens and people around the world are not left impotent.

Sign the petition telling EU leaders to stop mass surveillance here