30 Sep 2024 | Egypt, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

In his book You have not yet been defeated, the 42-year-old British-Egyptian imprisoned activist, software engineer, and writer, Alaa Abd el-Fattah writes: “I am in prison because the regime wants to make an example of us.” Yesterday, 29 September 2024, was due to be the end of his five-year sentence – but as this milestone passes with him still behind bars, his words remain true.

“[Alaa] is extremely nervous that this unprecedented move takes him beyond even arbitrary detention into something worse and that he may never be released,” Omar Hamilton, Abd el-Fattah’s cousin told Index on Censorship.

Abd el-Fattah has been imprisoned in Egypt for most of the last decade, aside from a brief period of release in 2019.

During President Hosni Mubarak’s regime, he became a vocal pro-democracy campaigner via his blog, Manalaa, which he ran with his wife, Manal Hassan. This increased during the 2011 Egyptian Revolution where he rose to prominence for his on-the-ground activism and political discourse.

Abd el-Fattah was arrested in November 2013, following the military coup led by now-President Abdel-Fattah el Sisi. He was sentenced to five years in prison for organising a protest.

After briefly being released, on 29 September 2019, he was once again detained along with his lawyer, Mohamed Baker, on several charges including “joining a terrorist group”, “funding a terrorist group”, “disseminating false news”, and using social media “to commit a publishing offence”. The pair were subjected to a grossly unfair trial and held in pretrial detention for 31 months. Yesterday, Abd el-Fattah completed his five-year sentence, which included his pretrial detention. However, the authorities show no signs of letting him go.

“I’m in detention as a preventative measure because of a state of political crisis – and a fear that I will engage with it,” said Abd el-Fattah in his statement to the prosecutor in January 2020.

During his time behind bars, Abd el-Fattah has been subjected to both physical and psychological torture. In 2022, the activist underwent an extended hunger strike and then refused water as COP27 began in Egypt. The strike was ended by force after prison authorities intervened.

In an interview with Index on Censorship in 2022, Abd el-Fattah’s sister, Mona Seif said: “In the eyes of the Egyptian regime Alaa is one of the symbols of [the] 25th January [2011 revolution] and therefore one of those calling for an end to the leadership of the military regime.

This much is true. While a few political prisoners in Egypt have been released over the years, Abd el-Fattah and Baker continue to be held with no sign of release. After all, it was President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi who personally ratified their verdicts in January 2022.

Abd el-Fattah is a British citizen and his family, also British citizens, have dedicated much of their campaign for his release to encouraging the UK government to take action.

“The Labour Government needs to show that it is not a continuation of the Conservatives, and David Lammy needs to prove that he did not make strident statements and promises to Alaa’s family when he was in opposition that he can just drop once in power,” Hamilton explained.

The Free Alaa campaign is calling on the British government to take real action to secure the release of one of its citizens. They are encouraging UK nationals to write to their MPs demanding that Abd el-Fattah is released.

The campaign claims that despite Foreign Minister David Lammy pledging his support for Abd el-Fattah’s release prior to the Labour government coming into power earlier this year, he has done little to secure his release.

“Alaa is a British citizen, and it is urgent that the UK government intervene now to stop this new violation of his human rights. The Foreign Secretary David Lammy has spoken up for Alaa in the past, but he must now turn those words into action,” Laila Soueif, Abd el-Fattah’s mother, wrote today via the Free Alaa campaign.

Soueif also announced that she will begin a hunger strike until Abd el-Fattah is free.

“My son had hope that the British government would secure his release. If they do not I fear he will spend his entire life in prison. So I am going on hunger strike for him, and I would rather die than allow Alaa to continue to be mistreated in this way.”

With international attention intensely focused on Israel, Gaza, and Lebanon, and Egypt’s Western allies content on overlooking el-Sisi’s human rights abuses to ensure security and stability within the region, it is hard to imagine that Abd el-Fattah’s case will be at the top of their agendas.

However, after 10 years of near-constant campaigning for his release, Abd el-Fattah’s family are not giving up and neither should we.

24 Sep 2024 | News and features

Banned Books Week is here once again. And so too are more stories of books being censored across the world. This week, Pen America reported that the number of book bans in public schools has nearly tripled in 2023-24 from the previous school year.

While the week-long Banned Books Week event, supported by a coalition including Index on Censorship, looks largely towards bans in the USA, we’re taking a moment to reflect on global censorship of literature. We asked the Index team to share what they think is the most ridiculous instance of book censorship, from the outright silly to the baffling but dangerous. Some of these examples verge on amusing — the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s aversion to talking animals, for example — but the bans that have ended in attempted murders just go to show that the practice of book banning itself is completely nonsensical, and can lead to real harm.

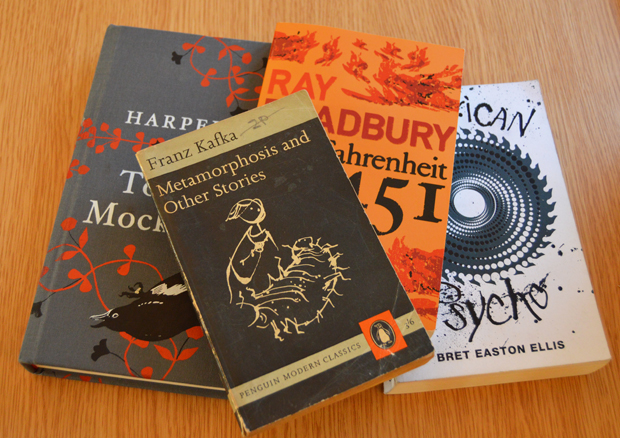

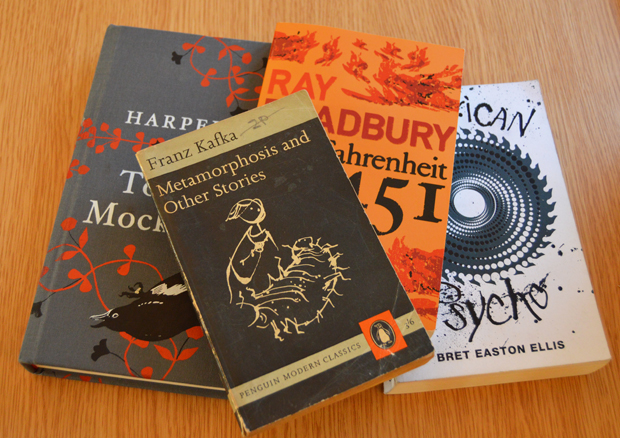

Banned Books (Photo by Aimée Hamilton)

Too many talking animals

You don’t have to have children to imagine what a clichéd kids book might look like. Yes, you’ve guessed right – animated animals. Tigers, mice, dogs – they’re all common in children’s literature. But the Chinese authorities have an uncomfortable relationship with our furry friends.

In 2022 a Hong Kong court sent five people to prison for publishing a series of books called Sheep Village (and of course they banned the books too). To be fair these illustrated books, aimed at kids aged four to seven, didn’t code their political messages well: a flock of sheep (stand-in for Hong Kongers) peacefully resist a savage wolf pack (the guys in Beijing). So this might not be the most absurd example, though it did feel like an absurdly low moment.

However, what was clearly absurd on all levels was the 1931 ban of Alice in Wonderland by the governor of Hunan Province. The book’s crime? Talking animals. Apparently they shouldn’t have used human language and putting humans and animals on the same level was “disastrous”. What unites the CCP with the Republic of China that came before it? Unease around anthropomorphised animals it would seem.

Too many banned books

Ban This Book by Alan Gatz, a book about book bans, has been banned by the state flying the banner for banning books. This is not a tongue twister, riddle or code. It is the crystallisation of the absurdity of banning books.

In January 2024, the book was banned in Indian River County in Florida after opposition from parents linked to Moms for Liberty. According to the Tallahassee Democrat, the school board disliked how the book “referenced other books that had been removed from schools” and accused it of “teaching rebellion of school board authority”. When you are trying to reshape the world in line with your own blinkered view it is probably best not to draw attention to it by calling out reading as an act of rebellion. Just a thought.

The book tells the story of Amy Anne Ollinger’s fight to overturn a book ban in her fictional school library. The book’s conclusion leads Amy Anne “to try to beat the book banners at their own game. Because after all, once you ban one book, you can ban them all”.

This tells us something – the self-harming absurdity of book bans is apparent to kids like Amy Anne but not to the prudish administrators and thuggish groups wielding their mob veto like a weapon. Groups like Moms for Liberty and their fellow censors obscure the darkness of our shared history by removing any reference to it and by pretending it did not happen — not by addressing the root causes or working to ensure it does not happen again.

- Nik Williams, policy and campaigns officer

Too Belarusian

In Belarus, numerous books in the Belarusian language by the country’s best classical and modern writers have been banned, especially following the 2020 presidential election and pro-democracy protests. Unbelievably, Lukashenka’s regime — often called the last dictatorship in Europe and backed by Russia — views Belarusian historical, cultural and national identity as a threat.

Many books in Belarusian have been labelled extremist and even destroyed from the National Library’s collection since the protests started in August 2020. This includes Dogs of Europe by Alhierd Baharevich, works by 19th century writer Vincent Dunin-Marcinkievich and 20th century poet Larysa Hienijush, among others.

- Jana Paliashchuk, researcher on Index’s Letters from Lukashenka’s Prisoners project

Too decadent and despairing

Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, possibly the greatest short story ever written, was banned by both the Nazis and the Soviets. Being a Jewish author, the Nazis burned Kafka’s books on their “sauberen” (cleansing) pyres. But in the Soviet Union, his books were banned as “decadent and despairing”. This was clearly a judgement made by officials without much knowledge of the history of the novel, where so many titles are filled with human despair. Without these, we would not get the contrasting light of decadent writers like Oscar Wilde and JK Huysmans.

- David Sewell, finance director

Too mermaidy

One of my favourite books to read with my son is Julian is a Mermaid by Jessica Love. It’s a beautiful picture book where a young boy dreams of becoming a mermaid after seeing a school / pod (collective noun to be determined) of merfolk on the way to the Coney Island Mermaid Parade, then rummages around his nana’s home for a costume.

In various parts of the USA, Julian has been banned. In a school district in Iowa, it was flagged for removal under a law that “bans books that depict or describe sex acts”, which apparently also covers gender identity — there are definitely no sex acts in this book. In other districts, it’s been fully banned due to representing the LGBTQ+ community.

If book banners in the USA are really worried about kids becoming mermaids, then I’d like to know on what grounds. Because, quite frankly, I always wanted to be a mermaid, and if it turns out it was a viable option, I have some regrets. Personally, I’d be more concerned about Julian ripping down his nana’s curtains to make a tail, à la Julie Andrews making costumes for the Von Trapp children.

- Katie Dancey-Downs, assistant editor

Too accurate

In Egypt, Metro, the country’s first graphic novel by Magdy El Shafee, was quickly banned after publication in 2008 for “offending public morals”. This was likely due to the novel’s depiction of a half-naked woman, inclusion of swear words and general portrayal of poverty and corruption in Egypt during the former president Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year rule. The author was charged under article 178 of the Egyptian penal code for infringing “upon public decency” and fined 5,000 LE. It was eventually republished in Arabic in 2012.

- Georgia Beeston, communications and events manager

Too dystopian

Aldous Huxley’s 1932 dystopian classic Brave New World explores an imagined future centred on productivity and enforced “happiness” at the expense of individual freedom. Set in 2540, society has been stripped of families, with babies manufactured synthetically with specific characteristics, then forced into a predetermined “caste” system. People are encouraged to prioritise short-term gratification through casual sex and taking a “happiness” drug called soma, making them blissfully unaware of their imprisonment within the system.

Since its publication nearly 100 years ago, the novel has caused controversy globally. It was initially banned in Ireland and Australia in 1932 for eschewing traditional familial and religious values, then later banned in India in 1967 for its sexual content, with Huxley even being referred to as a “pornographer” for depicting a society that encourages recreational sex. It is still banned in many classrooms and libraries across America for a range of wild reasons, from use of offensive language and sexual explicitness to racism and “conflict with a religious viewpoint”.

But Huxley’s imagined future is one of horror. He uses themes of enforced, unfettered pleasure and a twisted genetic-based class system to express how humans’ complex problems and moral quandaries cannot be solved by scientific advancement alone. The main point of dystopian fiction is to tell a cautionary tale of the levels of exploitation that society could sink to, in order to save the world at large. While it was undoubtedly shocking and crass for its time, the fact that Huxley’s novel still ruffles feathers reveals a complete misunderstanding of allegory.

Too many lesbians

I first read Radclyffe Hall’s legendary lesbian novel, The Well of Loneliness, published in 1928, with bated breath as a young, closeted queer person. Her portrayal of young woman ‘Stephen’ Gordon and her romance with Mary Llewellyn was wildly liberating and satisfying to read. Of course, as a product of its time it is in many ways outdated and of course laced with problematic values, for example biphobia and misogyny. But it was hugely important in terms of normalising queer relationships over a century ago.

Shortly after publication, the book went to trial in Britain on the grounds of “obscenity” and was subsequently banned — but this is no Lady Chatterley’s Lover. There are no real ‘hot under the collar moments’. The only ‘obscenity’ was the portrayal of two women in a romantic relationship, even though (unlike male homosexuality), lesbianism wasn’t actually illegal in 1928.

- Anna Millward, development officer

Too friendly

The award-winning writer and painter Leo Lionni’s first children’s book Little Blue and Little Yellow (1959) is a short story for young children about two best friends who, one day, can’t find each other. When they meet again, they give each other such a big hug that they turn green.

Despite its important message about the power of love and friendship, the mayor of Venice decided to ban it from all preschools in the province for “undermining traditional family values”. It was one of more than 50 children’s books to have been banned just days after he took up the post after his election in 2015.

- Jessica Ní Mhainín, head of policy and campaigns

Too uncensored

As ironies go, the banning of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 may be the strangest. The novel describes a dystopian future in which books are banned and “firemen” burn any that are found – its title comes from the ignition temperature of paper.

In 1967, a new edition of the book aimed at high schools, known as the Bal-Hi edition, was substantially altered to remove swear words and references to drug use, nudity and drunkenness. Somehow, the censored text came to be used for the mass-market edition in 1973 and “for the next six years no uncensored paperback copies were in print, and no one seemed to notice”, wrote Jonathan R. Eller in the introduction to the 60th anniversary edition of the book.

Readers eventually realised and alerted Bradbury. He demanded that the publisher retract the censored version, writing that he would “not tolerate the practice of manuscript ‘mutilation’”.

- Mark Stimpson, associate editor

Too unflattering

It’s not altogether surprising that UK authorities attempted to prevent the autobiography of former MI5 officer Peter Wright, Spycatcher (co-written by Paul Greengrass), from hitting the shelves. The book did not present British intelligence agencies in a flattering light, and the government’s claims that they were suppressing its publication in the interests of security — rather than to save face — were eventually dismissed by the courts.

However, the ridiculous part about this book banning was that it only applied to England and Wales and the book was freely accessible elsewhere — including Scotland. This led to an absurd situation where newspapers around the world were reporting on the book’s contents while the press in England was subject to a gagging order, despite the information having already been revealed and books being easily shipped into the country. The ban was eventually lifted after it was acknowledged that the book wasn’t exposing any secrets due to its overseas publication.

- Daisy Ruddock, CASE coordinator

Too blasphemous

The most absurd book banning is also, arguably, the most serious in recent history. The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie was published in 1988 to deserved critical acclaim. It is a playful and complex novel that examines, among other things, the origins of Islam. The death sentence imposed on the author by Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini was fuelled by, and in turn itself fuelled an ideology that believes that a novel can be blasphemous and its author should be killed. It would be laughable if the consequences weren’t so deadly.

- Martin Bright, editor at large