27 Dec 2013 | News

In a new sign that Egypt’s military-backed regime is widening its crackdown on dissent, three prominent activists and symbols of the January 2011 Revolution were sentenced to 3-year jail terms by a Cairo court this week.The court also ordered the activists to pay a fine of LE 50,000 each .The case has fuelled fears of increased government repression in a country wracked by violence since the toppling of Islamist President Mohamed Morsi by military-backed protests in July.

In a new sign that Egypt’s military-backed regime is widening its crackdown on dissent, three prominent activists and symbols of the January 2011 Revolution were sentenced to 3-year jail terms by a Cairo court this week.The court also ordered the activists to pay a fine of LE 50,000 each .The case has fuelled fears of increased government repression in a country wracked by violence since the toppling of Islamist President Mohamed Morsi by military-backed protests in July.

On Thursday, founder of the April 6 Youth Movement Ahmed Maher, member of the group’s political bureau Mohamed Adel and political activist Ahmed Douma began a hunger strike to protest “harsh treatment” at Cairo’s Torah Prison where they are being held. The pro-democracy activists were among 51 activists detained last month after organizing a demonstration to protest a controversial new law that the government claims will “regulate protests”. They were accused of allegedly “assaulting police officers, thuggery and organizing a protest without obtaining a permit from the authorities.” Rights groups have condemned the jail sentences, expressing concerns that the Egyptian authorities were “reversing the hard-earned gains of free speech and assembly acquired following the January 2011 uprising that toppled Hosni Mubarak.

In a statement posted on the April 6 website, the activists denounced the “inhumane conditions” they have endured in prison . They also complained of maltreatment and abuse by fellow inmates.

The activists’ statement coincided with a government announcement that the Muslim Brotherhood had been declared a “terrorist organisation”–a move signaling further marginalisation of the Islamist group in the bitterly polarized country .The government decision came a day after a fatal suicide bombing that targeted the Security Directorate in the Nile Delta city of Mansoura. At least 12 people were killed and 130 others were wounded in the attack for which a Jihadi group – Ansar Beit al Maqdis–later claimed responsibility. Despite the Muslim Brotherhood’s denunciation of the terror attack on their official website Ikhwanweb, the government announced plans to criminalize the group’s activities and freeze its funds–a move the analysts feared would lead to greater radicalization of the group and plunge the country into civil strife.

General Coordinator of the April 6 Youth Movement, Amr Aly criticised the government decision saying that ‘branding the Brotherhood a terrorist organisation would not halt the attacks but would end hopes for stability, plunging the country in a state of chaos.”

As Egyptians were still reeling from the shock of Tuesday’s deadly bombing in Mansoura, news broke of a second blast in Cairo’s residential neighborhood of Nasr City on Thursday . The latest explosion–caused by a homemade bomb–injured five passengers on a bus.raising fears of a fresh spate of attacks ahead of a popular referendum on the new constitution scheduled for mid January.

Hours after Thursday’s attack, 16 Muslim Brotherhood supporters were arrested in the Nile Delta province of Sharkiya on charges of “promoting the ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood group, distributing leaflets, and inciting violence against the army and police.” Egypt’s privately-owned TV channel CBC meanwhile, announced the numbers for a new Hotline, urging citizens to report people they suspect of having links to the “terrorist group.”

The recent repressive measures have been described by analysts as a “dramatic escalation in a long-running feud between Egypt’s security agencies and the Islamist group intended to paralyse the latter and block any space for the Brotherhood in the political process.” But with the crackdown now expanding to target secular revolutionary activists, many are concerned that Egypt’s “democratic transition” may have taken a wrong turn, leaving the country on the brink of a civil war that may tear it apart.

12 Dec 2013 | Egypt, Middle East and North Africa, News

An Egyptian appeals court on Saturday revoked harsh 11-year jail sentences handed down in November to 14 girls and women for staging a protest in Alexandria demanding the reinstatement of toppled President Mohamed Morsi. The 14 defendants were given suspended sentences of one year in prison each after the earlier verdicts provoked a public outcry and drew fierce criticism from local and international rights groups.

An Egyptian appeals court on Saturday revoked harsh 11-year jail sentences handed down in November to 14 girls and women for staging a protest in Alexandria demanding the reinstatement of toppled President Mohamed Morsi. The 14 defendants were given suspended sentences of one year in prison each after the earlier verdicts provoked a public outcry and drew fierce criticism from local and international rights groups.

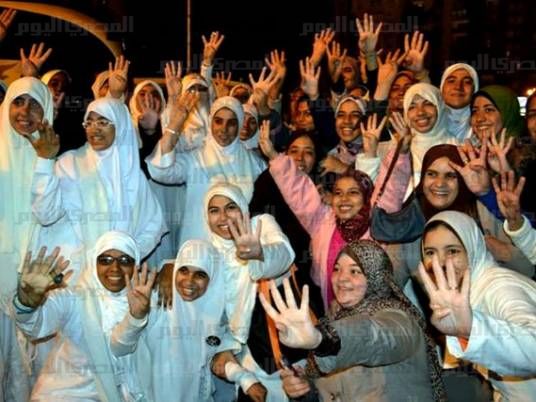

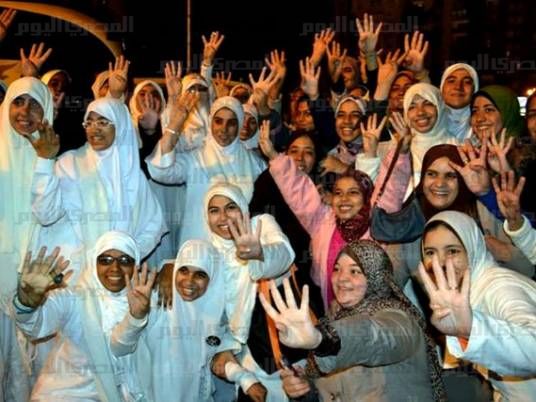

Seven minors — aged 15 and 16 — who had also taken part in the Alexandria 31 October protest were acquitted by the court but are to remain on probation for the next three months.The young defendants who were released on Saturday after a month in custody, had previously been ordered detained in a juvenile centre until they turned 18 . The girls are members of the so-called “7am movement” that had recurrently held early morning “anti coup” protests outside a school in the Mediterranean port city.

All 21 defendants had been charged with ” thuggery, vandalism , illegal assembly and use of weapons” — charges that rights groups insist were “politically motivated”. In a statement condemning the November verdicts, Amnesty International described the girls as “prisoners of conscience” and said their detention reflects the Egyptian authorities determination to punish dissent. Human Rights Watch , HRW, meanwhile said “the court had violated the right to free trial as witnesses were barred from testifying in the girls’ defence.” Little evidence was provided for the charges the girls faced”, HRW added.

Egyptian rights groups also expressed concern over the jail terms and agreed that the defendants faced “trumped up charges”

“Such verdicts raise doubts about the independence of the judiciary in Egypt and signal a return to the Mubarak era when the courts were often used as a political tool against the opposition,”the Cairo-based Arab Network for Human Rights Information, ANHRI, said in a statement released after the verdicts were announced by a Misdemeanour Court. In a statement issued on the Muslim Brotherhood’s official website Ikhwanweb , the Freedom and Justice Party, the political arm of the Islamist group also denounced “the unjust “verdicts sentencing the girls to long jail terms for what the FJP said were “peaceful protests”.

Images of the young defendants clad in white prison garments and headscarves were widely circulated on social media networks, fuelling the anger of Egyptian activists–including many who participated in the June 30 uprising demanding that President Morsi step down. In a message posted on Twitter on 27 November (the day the verdicts were announced), blogger Zeinobia stated “Today Egypt jailed 14 girls for holding balloons at a protest!”.

Other activists expressed their dismay saying they believe the convictions are “part of a nationwide crackdown on Muslim Brotherhood supporters and efforts by the interim government to silence dissent.” They drew comparisons between police officers accused of killing protesters escaping justice while the girls were convicted for exercising their right to protest peacefully. In a Twitter post, rights lawyer and Head of the AHRNI Gamal Eid wrote ” the same judiciary that released Wael El-Komi, an Alexandria police officer accused of killing no fewer than 37 protesters, has sentenced 14 girls to 11 years in prison.”

“The state where there is respect for rule of law welcomes you!” he sarcastically added .

Egyptian authorities insists they are “waging a war against terrorists seeking to destabilize the country”. Thousands of Islamists have been detained since Morsi’s overthrow by military supported protests on 3 July and hundreds of pro-Morsi protesters were killed when security forces dispersed two Cairo sit-ins in mid-August, in what rights advocates have described as “the worst massacre in modern Egyptian history.”

In recent weeks the military-backed government has widened its crackdown, detaining dozens of secular pro-democracy activists who have helped the military consolidate its power by participating in the June 30 uprising against the previous Islamist government. Prominent political activists Alaa Abdel Fattah, Ahmed Maher and Ahmed Douma were among protesters detained two weeks ago for violating a new law regulating protests. They face investigations and have been referred to military courts on charges of allegedly “inciting protests, thuggery and resisting security forces”.

The excessive use of force by security forces in dispersing the recent protests and the harsh verdicts for the Alexandria girls signal a return of rights violations reminiscent of the Mubarak era, serving as a warning message that the authorities will stop at nothing to silence dissent.

This article was posted on 12 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

3 Dec 2013 | Egypt, News, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

Egyptians gathered on the in Corniche near Qasr Nil Bridge in July 2013 to celebrate news of the announcement by the Egyptian Army Chief General el Sisi, that President Morsi had been removed from power in “response to the will of the people.” (Photo: Sharron Ward / Demotix)

Last week, when Egyptian security forces violently dispersed activists rallying against a controversial new anti-protest law, Egyptian media was full of praise for them the following day. Instead of condemning the excessive use force by riot police who beat, sexually assaulted and detained scores of opposition protesters, newspaper editors portrayed the Interior Ministry as “the victor” in the confrontation over the new gag law.

“The Interior Ministry has passed the test on the anti-protest law,” read Wednesday’s bold red headline in the semi-official Al Ahram daily. The independent Al Watan, meanwhile, declared on its front page that the Ministry of Interior had “decidedly resolved the battle over the anti-protest law.”

Headlines, editorials and articles labelling democracy activists “anarchists and “thugs” signal that most Egyptian media has reverted to its old pre-revolution ways, siding with the military-backed government against the opposition. During the January 2011 mass uprising that toppled former President Hosni Mubarak, Egyptian media had vilified the opposition activists, describing them as “foreign agents” and “hired thugs.”

Media discourse in Egypt today is reminiscent of the Mubarak era. Then, almost all media outlets had adopted the state line and carefully avoided crossing the so-called ‘red lines’. The only difference is that today, the media has voluntarily and ungrudgingly aligned itself with the military-backed government. During Mubarak’s tenure journalists were motivated by fear of falling out of favour with the authoritarian regime. Ironically, since Muslim Brotherhood President Mohamed Morsi was toppled by military-backed protests last July, the Egyptian media’s support for the country’s powerful military has come with little coercion from the generals who are riding a wave of popularity and ultra-nationalist sentiment.

Since Morsi’s ouster, the Egyptian media has glorified the military while persistently demonising both the Muslim Brotherhood and the deposed Islamist President, continuing the vilification trend it had started when the former president was still in power. Morsi’s supporters have consistently been branded “terrorists” and “liars” by Egypt’s state-owned and private media alike. As Morsi’s supporters staged a sit in last July demanding “the reinstatement of the legitimate president”, Youssef El Husayni, a presenter on the privately-owned channel ON TV accused the protesters of murder, saying that they “deserved to be hanged.” Other TV talk show hosts also accused the anti-coup protesters of “getting paid to stay on the streets”. On November 4, the day Morsi’s trial began, the former president was labelled “hysterical” by several Egyptian newspapers including the independent El Youm el Sabe’e and El Masry El Youm for insisting he was still the country’s legitimate president and could not be tried by the court. He was also criticized by journalists for refusing to wear his prison uniform to court–a decision that drew unfavourable comparisons with his predecessor Hosni Mubarak who had previously appeared in court in the white garment.

Earlier this month, the privately-owned network CBC suspended satirist Bassem Youssef’s wildly popular show Al Bernameg (The Programme) after an episode that poked fun at the public fervour for the military and in particular, at the ‘Sissi-mania’ gripping the country. Egypt’s De facto ruler El Sissi earned the adoration of millions of Egyptians when he ousted Morsi, positioning himself as the “guardian of the people’s will” and claiming he had “saved the country from a looming civil war.” He has since been compared by some Egyptian media to Egypt’s former ultra-nationalist leader Gamal Abdel Nasser. In recent months, there have increasingly, been calls for El Sissi to run in the next presidential election.

Surprisingly, the decision to take Youssef’s show off the air came from CBC’s senior management not–as many had initially believed–from strongman El Sissi. Youssef’s last episode met with a public outcry and almost immediately after the broadcast, CBC issued a statement distancing itself from the comedian’s views. The station blamed the suspension of the show on “technical” and “business” issues rather than on the show’s editorial content. CBC’s decision has led to fierce public criticism of the network which had previously given Youssef a free hand to mock former President Mohamed Morsi and his Islamist group. Throughout Morsi’s one year term in office, Youssef had relentlessly kept up his attacks on the former President despite repeated threats of legal action against him. Many of Youssef’s fans have threatened to boycott CBC after the TV satirist quit the channel over the suspension of the show.

Meanwhile, the “red lines” are back at Egyptian State TV where show presenters and anchors have kept up the pro-military rhetoric in recent months for fear of being stigmatized as “pro-Muslim Brotherhood ” and “fifth columnists.” The latter is a term that is being widely used to describe sympathizers or supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood whose activities were banned by a court ruling in November. Presenters who are suspected of being sympathetic to the outlawed Islamist group are being deprived of air time. Several presenters have faced investigations in recent weeks over “their shameful links to the enemy Islamist group”. Journalists have been repeatedly accused of “destroying the country and wreaking havoc to abort the goals of the revolution.” A list of names of so-called “fifth column TV presenters and activists” has gone viral on social media networks Facebook and Twitter after being posted on several local websites with the declared aim of “exposing and sidelining the traitors.” Those on the list–which includes reform leader El Baradei, revolutionary activists and prominent TV journalists known for their objectivity–have also being accused of receiving foreign funding.

Many journalists have again resorted to practising self-censorship for fear of being labelled “enemies of the state.” Ironically, the pressure on them has come from fellow-journalists rather than from the generals themselves. Those piling the pressure are journalists who were either appointed by the ousted Mubarak regime or others with strong links with the country’s notorious security services. In September, controversial talk show host Tewfik Okasha, who is also the owner of the private El Fara’een Satellite Channel, gave Defence Minister El Sissi “an ultimatum to purge the media of fifth columnists”. Abdel Rahim Ali, the chief editor of El Bawaba news site, meanwhile told Al Midan TV in September that “those who oppose the reinstatement of state security are from the fifth column.” He did not hesitate in naming the activists and political figures he suspected had links with the “Islamist terror organization.” Responding to a list of suspect-fifth columnists published in the state-owned Al Ahram El Arabi in September, veteran columnist Fahmi Howeidi warned that “such accusations only serve to further empower the country’s notorious state security service, the SSS.” The SSS, known in Egypt as “Amn El Dawla” was a symbol of police oppression under ousted President Hosni Mubarak. It was disbanded in March 2011 only to return a month later, albeit under a different name–the National Security Service.

The “Fifth Column Campaign” targeting government critics with the aim of silencing voices of dissent, has succeeded in fulfilling its objective, lament rights campaigners.

“In this atmosphere of deep political divisions and at a time when anyone can be accused of espionage for merely mentioning such ‘taboo’ words as ‘coup’ and ‘reconciliation’, many in our profession have opted to play it safe by siding with the stronger power–the military. This is an indirect way of muzzling the press and unfortunately, it is working,” Sameh Kassem, Cultural Editor who works for the independent Al Dostour said.

In the ‘new Egypt’ –now once again under the tight grip of military rule — where scores of journalists have been assaulted and detained for covering the anti-coup protests, the critics are falling silent.

This article was published on 3 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

29 Nov 2013 | Academic Freedom, News, United Kingdom

In bid to address the issues surrounding people with extremist views giving talks at British campuses, Universities UK recently released new guidelines on external speakers. “Universities have to balance their obligation to secure free speech with their duties to ensure that the law is observed — which includes promoting good campus relations and maintaining the safety and security of staff, students and visitors,” says the body, which represents vice-chancellors.

This is not the first time they have spoken out about the topic. However, a set of guidelines from 2011 reads: “It is the law alone which can set restrictions on freedom of speech and expression and on academic freedom — it is for the law and not for institutions or individuals within institutions to set the boundaries on the legitimate exercise of those rights”. It appears they are calling for somewhat stricter regulation this time around. The current guidelines are also more in line with the view of the National Union of Students, which maintains that “(…) many students’ unions may wish to go further than the law on securing ‘freedom from harm’ when restricting some speaker activity.” The NUS’ own “No Platform” policy, banning certain speakers from their events, puts this theory into practice.

This is one of those topics that seems to come up at fairly regular intervals, and the outline of the debate is familiar by now. One side argues that speakers with outwardly hateful or discriminatory views don’t deserve a platform through which to legitimate them; while the other side argues that to deny them this is to deny them the right to freedom of expression, which also extends to those with whom we disagree. The following speakers have been responsible for at one point reigniting the debate, each in their own way.

1) Nick Griffin

Nick Griffin outside the Old Bailey court on the first day of the trial of the murder of Lee Rigby (Image: Velar Grant/Demotix)

The most famous case in recent years was the 2007 appearance of BNP leader Nick Griffin (and Holocaust-denying historian David Irving) at an Oxford Union debate on free speech. The invitation caused massive uproar, with protesters picketing the event. “It is not just an Oxford issue, this will have ramifications for other places where the BNP are active… this is going to give legitimacy and credibility to their views,” said Student Union President Martin McClusky at the time. “I find the views of the BNP and David Irving awful and abhorrent but my members agreed that the best way to beat extremism is through debate,” argued Oxford Union president Luke Tryl. This is not only time the Nick Griffin has caused controversy as a potential university speaker. Trinity College Dublin cancelled plans to include him in a debate immigration, saying “it could not guarantee the safety and wellbeing of staff and students”.

2) Mufti Ismail Menk

Mufti Ismail Menk giving a lecture (Image: soukISLAM/YouTube)

Islamic preacher Mufti Ismail Menk spoke at Liverpool University earlier this month. He has previously stated that gay people are “filthy” and “worse than animals”. The event was initially reported to be part of a longer tour stopping at Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool, Leicester, Cardiff and Oxford universities. However, all except Liverpool, where he was hosted by the Islamic Society, revoked their invitation or said he had not been officially invited in the first place. Liverpool responded that it is “not the role of the university to censor people’s views”.

3) Mohamed El-Nabawy

A video captured the protest that erupted when Mohamed El-Nabawy was due to speak at SOAS (Image: YouTube)

A representative of Tamaroud, the grassroots movement which played a significant role in the ousting of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood-backed elected government, was chased away by angry protesters prior to a scheduled talk at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). The protesters, who were not students, chanted and brandished posters associated with the Muslim Brotherhood at the open lecture. SOAS security had to escort El-Nabawy off campus using an emergency exit . A spokeswoman for the Palestinian Society, which had organised the talk, said: “In the pursuit of freedom of speech and expression, some people may find some of the views expressed at our events objectionable.”

4) David Gale

David Gale on the BBC’s Sunday Politics Show (Image: UKIPDerby/YouTube)

In 2012 the Student Union at the University of Derby banned David Gale, UKIP’s candidate for Police and Crime Commissioner, from taking part in a Q&A session at the university. The Union has a no platform policy for “individual(s) who they believe to be a member of a group with racist, fascist or extremist views”, a category the Union believed was applicable to UKIP . UKIP leader Nigel Farage weighed in on the issue at the time, saying: “It is frightening that a Derby student body is so frightened of free speech and public opinion.”

5) George Galloway

George Galloway attends an anti-war rally in 2011 (Image: Paul Soso/Demotix)

In March, George Galloway was set to speak at an event organised by the University of Chester Debating Society. However, the invitation was revoked by the Student Union, acting in line with the NUS’ No Platform policy on Galloway. This move came after the Respect Party MP was involved in a string of controversial incidents, including refusing to debate with an Israeli student at an Oxford University panel discussion. Galloway’s camp have called the policy “idiotic, anti-democratic and politically-motivated”.

6) Julie Bindel

In September, the Debating Union at Manchester University (MDU) invited feminist writer and campaigner Julie Bindel to speak at their discussion on pornography. A number of people objected due to Bindel’s reported views about transexual people, which have led to the NUS implementing a No Platform policy for her. Some transexual students and their supporters “felt Julie Bindel’s transphobic statements and views made them both unwelcome at the event, and unsafe on campus, as it seemed that transphobia was being allowed and possibly encouraged,” said Loz Webb, the university’s Trans* representative. Despite this, MDU refused to replace Bindel, though she eventually chose to drop out after receiving death threats.

This article was originally posted on 29 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

In a new sign that Egypt’s military-backed regime is widening its crackdown on dissent, three prominent activists and symbols of the January 2011 Revolution were sentenced to 3-year jail terms by a Cairo court this week.The court also ordered the activists to pay a fine of LE 50,000 each .The case has fuelled fears of increased government repression in a country wracked by violence since the toppling of Islamist President Mohamed Morsi by military-backed protests in July.

In a new sign that Egypt’s military-backed regime is widening its crackdown on dissent, three prominent activists and symbols of the January 2011 Revolution were sentenced to 3-year jail terms by a Cairo court this week.The court also ordered the activists to pay a fine of LE 50,000 each .The case has fuelled fears of increased government repression in a country wracked by violence since the toppling of Islamist President Mohamed Morsi by military-backed protests in July.

An Egyptian appeals court on Saturday revoked harsh 11-year jail sentences handed down in November to 14 girls and women for staging a protest in Alexandria demanding the reinstatement of toppled President Mohamed Morsi. The 14 defendants were given suspended sentences of one year in prison each after the earlier verdicts provoked a public outcry and drew fierce criticism from local and international rights groups.

An Egyptian appeals court on Saturday revoked harsh 11-year jail sentences handed down in November to 14 girls and women for staging a protest in Alexandria demanding the reinstatement of toppled President Mohamed Morsi. The 14 defendants were given suspended sentences of one year in prison each after the earlier verdicts provoked a public outcry and drew fierce criticism from local and international rights groups.