Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Richard Patterson/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[streamquiz id=”6″][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Governments are using the Covid-19 crisis to change freedom of information laws and, unless we are very careful, important stories could get unreported. Since the beginning of the crisis, governments from Brazil to Scotland have made changes to their FOI laws; some of the changes are rooted in pragmatism at this unprecedented time; others may be inspired by more sinister motives.

FOI laws are a vital part of the toolkit of the free media and form a strong pillar that supports the functioning of open societies.

According to a 2019 report by Unesco – published some two and a half centuries after the first such law was introduced in Sweden – 126 countries around the world now have freedom of information laws. These typically allow journalists and the general public the right to request information relating to decisions made by public bodies and insight into administration of those public bodies.

US president Thomas Jefferson once wrote: “Whenever the people are well informed, they can be trusted with their own government; that whenever things get so far wrong as to attract their notice, they may be relied on to set them to rights.”

Now in this time of crisis, freedom of information processes are being shut down, denied unless they relate specifically to the crisis or the deadlines for responses are being extended.

When the Covid-19 crisis first erupted, we made a decision to monitor attacks on media freedom. It wasn’t just a random idea; we know that in similar times of crisis, repressive governments often attack the work that journalists do – sometimes the journalists themselves – or introduce new legislation they have wanted to do for some time and now see a time of crisis as an opportunity to do so without proper scrutiny.

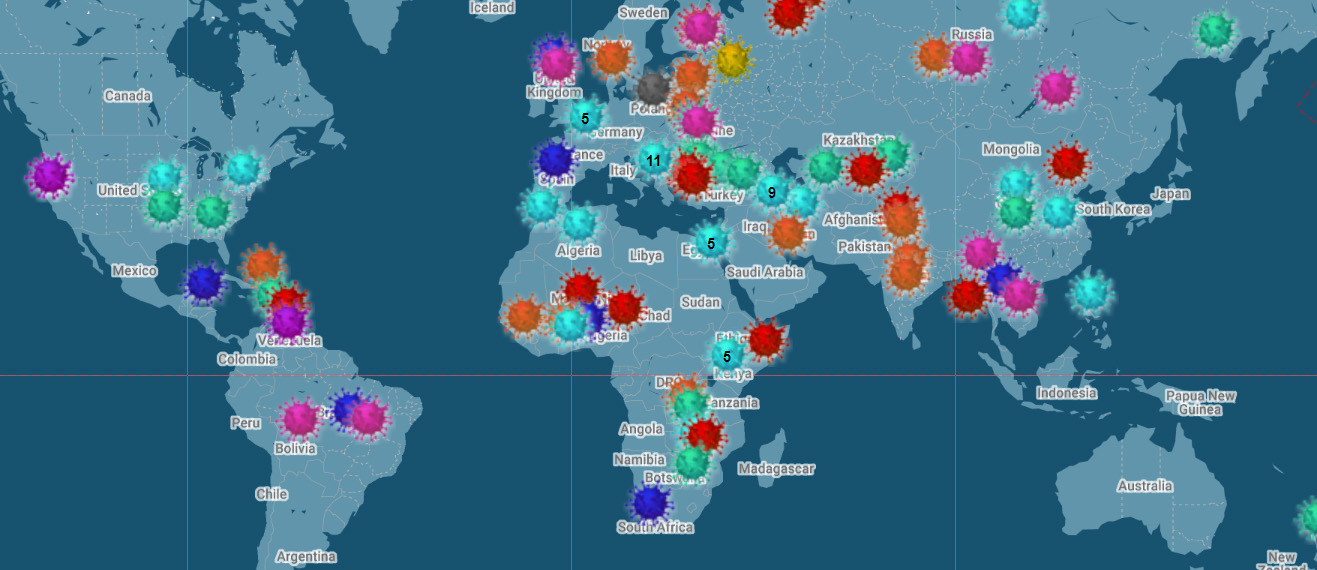

Since the start of the crisis, we have been collecting reports on attacks on media freedom through an innovative, interactive map. More than 125 incidents have been reported by our readers, our network of international correspondents, our staff in the UK and our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation. Many relate to changes to FOI legislation.

Let us be clear there can be legitimate reasons for amending legislation in times of international crisis. With many public officials forced to work from home, many do not have access to the information they need or the colleagues they need to consult to be able to answer journalists’ requests. Others need more time to be able to put together an informed response.

Yet both restrictions and delays are worrying. They allow politicians and public bodies to sweep information that should be freely available and subject to wider scrutiny under the carpet of coronavirus. News that is three months old is, very often, no longer news.

In its Coronavirus (Scotland) Bill, the Scottish government has agreed temporary changes to the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 that extend the deadlines for getting response to information requests from 20 to 60 working days. The initial draft wording sought to allow some agencies to extend this deadline by a further 40 days “where an authority was not able to respond to a request due to the volume and complexity of the information request or the overall number of requests being dealt with by the authority”. However, this was removed during the reading of the bill following concerns raised by the Scottish information commissioner.

The bill was passed unanimously on 1 April and became law on 6 April. As it stands the new regulations remain in force until 30 September 2020 but can be extended twice by a further six months.

In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro has issued a provisional measure which means that the government no longer has to answer freedom of information requests within the usual deadline. Marcelo Träsel of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism says the measure is “dangerous” as it gives scope for discretion in responding to requests.

The decree compelled 70 organisations to sign a statement requesting the government not to make the requested changes, saying “we will only win the pandemic with transparency”.

Romania and El Salvador are among the other countries which have stopped FOI requests or extended deadlines. By contrast, countries such as New Zealand have reocgnised the importance of FOI even in a crisis. The NZ minister of justice Andrew Little tweeted: “The Official Information Act remains important for holding power to account during this extraordinary time.”

FOI law changes are not the only trends we have noticed.

Index’s deputy editor Jemimah Steinfeld has noted how world leaders are ducking questions on coronavirus while editorial assistant Orna Herr has written about how the crisis is providing pretext for Indian prime minister Narendra Modi to increase attacks on the press and Muslims.

If you are a journalist facing unreasonable delays in receiving information from public bodies at this time, do report it to us at bit.ly/reportcorona.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Gang member Jonathan Martínez Castro was sentenced to 30 years in prison by a San Salvador court on 31 May for the murder of Canal 33 cameraman Alfredo Hurtado. Two gunmen shot Hurtado while he was visiting Ilopango, on the outskirts of the Salvadorian capital, on 25 April 2011. Hurtado had often covered gang member arrests, and it has been reported that the Mara Salvatrucha gang, of which Martínez Castro was a member, had suspected Hurtado had identified two of its members to the police as the murderers of another gangster. Martínez Castro’s alleged accomplice, Marlon Abrego Rivas, is currently a fugitive.

Last week, the online newspaper El Faro ran a story on how the Salvadoran government negotiated a truce with criminal gangs, known as “maras”, just before recent midterm elections. According to El Faro, the recent transfer of dangerous gang leaders from high security prisons to low security facilities was part of the deal. In exchange, the gangs, which contribute much to the high violence statistics in El Salvador, reduced their murder rate, the publication claimed.

But as soon as El Faro published the story all hell broke lose. The mnister of Justice and Security, General David Munguia Payes, held a press conference, to which El Faro was not invited. After denying the existence of a pact between the government and the criminal gangs, the minister said the work of El Faro was dangerous.

El Faro maintained that the job of a news organisation is to question government policies and challenge views held up by the powers at be. However, the outlet added, in weak democracies like El Salvador this could bring on added problems.

Carlos Dada, director of El Faro, said the government has told them they have intercepted messages between gang leaders where they have expressed their dissatisfaction with El Faro’s reporting. “But the government has not offered us any protection,” he said.

El Faro has been in the eye of the storm since it criticized the selection of military officers to run the police and security offices — something they say is forbidden under El Salvador´s 1992 peace accords, which ended a 12-year civil war.