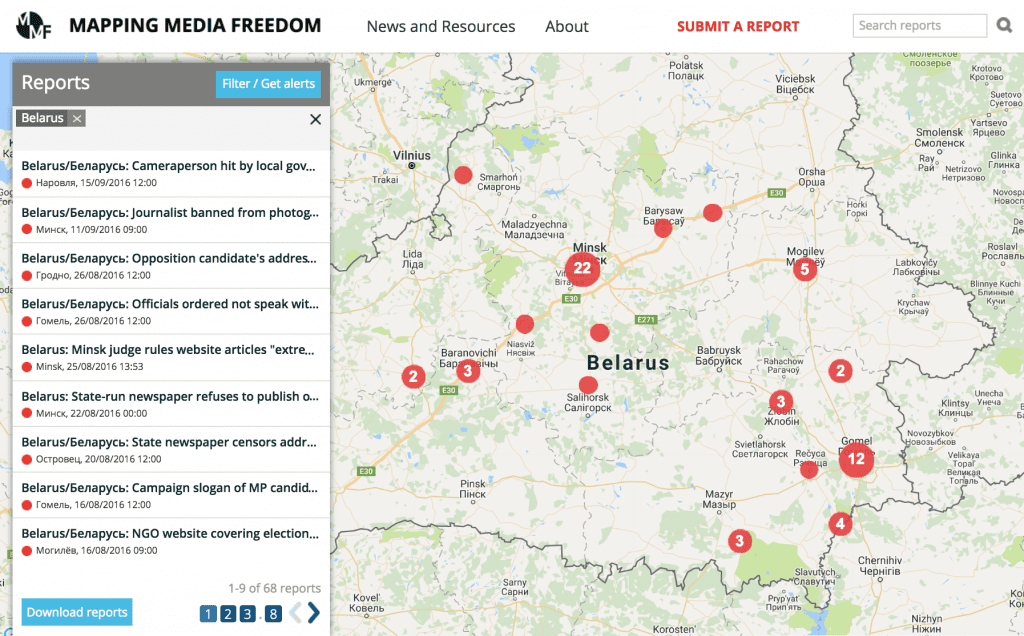

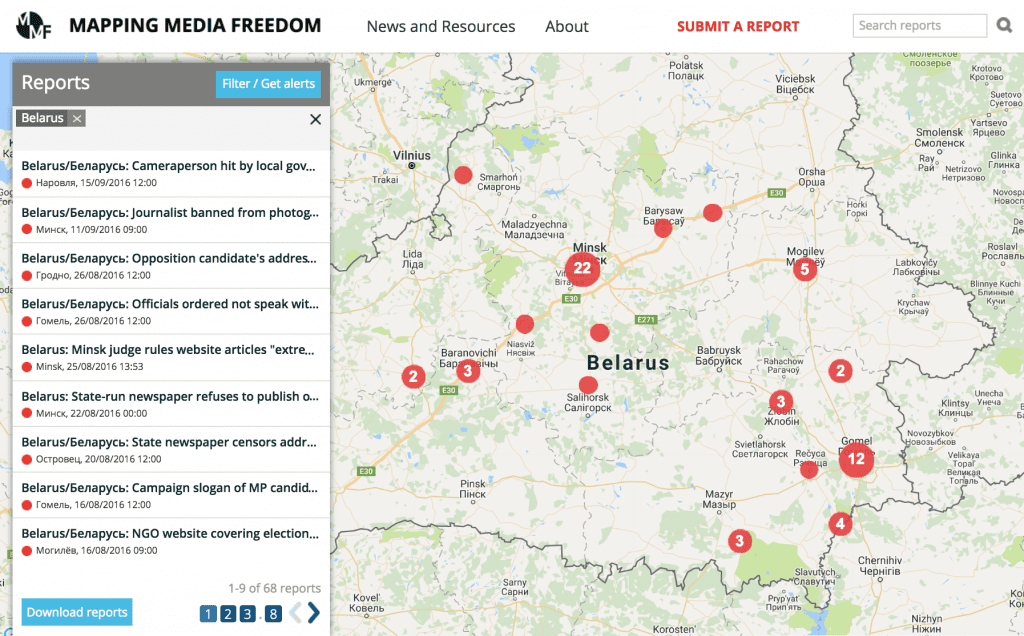

1 Nov 2016 | Belarus, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

On 11 September, the people of Belarus elected the lower house of parliament, the House of Representatives.

Speaking about the media environment surrounding the elections, the United Nations special rapporteur on human rights in Belarus, Miklós Haraszti, said: “It is regrettable that Belarus did not take into account real changes towards equal media access, verifiable turnout, honest vote count, and a pluralistic parliament. These changes have been recommended for many years by the OSCE, and my own reports.”

As in previous elections, independent journalists were denied access to information about the work of electoral commissions. On 10 August, during a district election commission meeting in the town of Barysau, the deputy chairman refused to answer a question about the candidates for the lower chamber of the Belarusian parliament posed by editor-in-chief of local independent newspaper Borisovskiye novosti, Anatol Bukas. A complaint filed by Bukas to the Central Election Commission was dismissed.

On election day, a correspondent for the independent newspaper Nasha Niva was forbidden to take photos at the polling station where the president of Belarus, Alexander Lukashenka, was supposed to vote. Security guards in civilian clothes said the journalist had not been accredited.

Opposition candidates faced arbitrary bans and censorship in publishing their “election programmes”, which lay out their platforms. Under Belarusian law, state-run media outlets should give an equal opportunity to all candidates to publish their programmes, but editors of state-run media refused to publish some which contained criticism of the authorities. The candidates referenced the election law, but have not been told of any specific violations in the texts. Complaints by the MP candidates have not been responded to by officials.

State-run newspaper Vecherniy Minsk refused to publish an election programme by opposition activist and Belsat TV’s anchorman Yury Khashchavatski. Vecherniy Minsk’s editor-in-chief Syarhei Protas wrote that the election programme “cannot be published because it does not comply with the requirements of Articles 47 and 75 of the Electoral Code of the Republic of Belarus”.

These articles state that “a candidate’s program must not contain propaganda for war, incitement to violent change of the constitutional order or violation of territorial integrity of the Republic of Belarus, to social, national, religious and racial hatred”.

A candidate’s programme must also not encourage or call up to obstruction, cancellation, or postponement of elections and there should be no insults or slandering against Belarusian officials or other candidates. However, the editor of Vecherniy Minsk did not indicate which statements of Khashchavatski were supposedly illegal.

According to Yury Khashchavatski, he never violated the law in his election programme and the editor might not have liked some his words about president Lukashenka.

A candidate from the United Civil Party Mikalay Ulasevich found himself in the same situation when local state-run newspaper Astravetskaya Prauda in Astravets, in Hrodna region, refused to publish his election programme referring to the same grounds. Moreover Hrodna regional state television did not broadcast Ulasevich’s speech. In his address to electors, which was recorded but not aired at the scheduled time, Ulasevich opposed the construction of a nuclear power plant in Belarus and spoke about a corruption problem in the country. Mikalay Ulasevich is behind the public initiative Astravets Nuclear Power Plant Is A Crime. According to Belarusian law, all candidates have a right to broadcast election speeches on state-run TV during the election campaign.

Giving an assessment of media freedom during the last parliamentary election Andrei Bastunets, Chairperson of BAJ, said: “We explain some easing of pressure on journalists during the elections with the desire of the Belarusian authorities to obtain a positive assessment of the election campaign by the international structures. It follows on the need to seek credits in the conditions of economic crisis and does not expel resumption of the previous practice of persecution of journalists after the elections.”

22 May 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Politics and Society, Ukraine

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

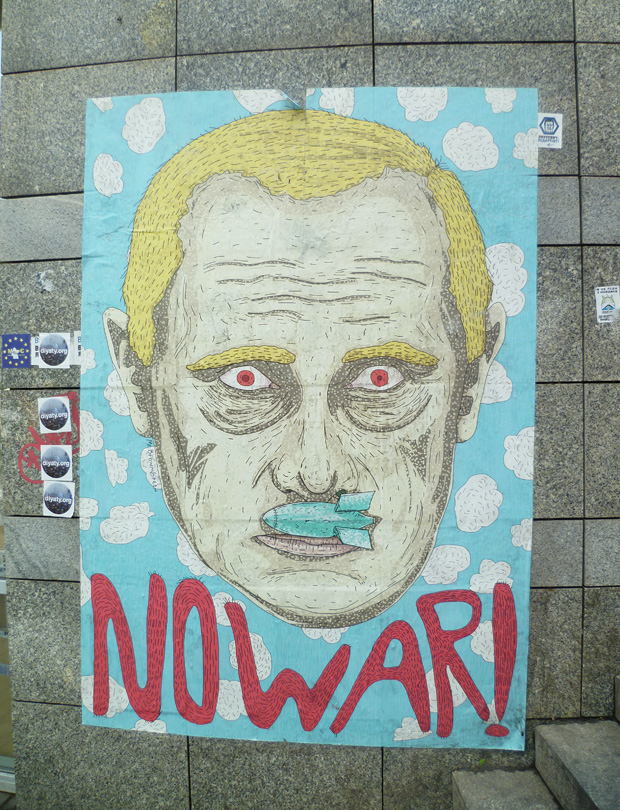

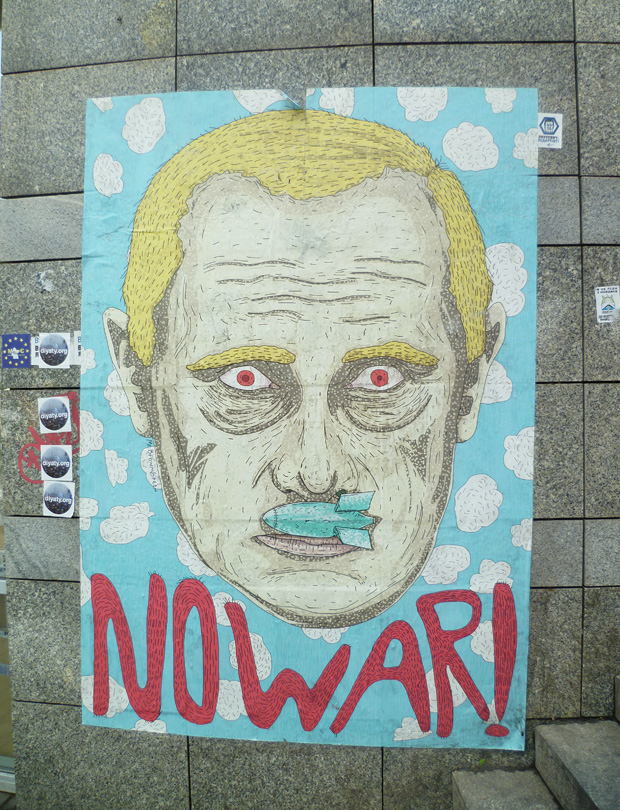

Walking around Kiev’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti square, months after the protest that enveloped the city and toppled the corrupt government of Viktor Yanukovych died down, is a strange experience. International attention has understandably shifted, the images now beamed across the world are from the ongoing crisis in eastern Ukraine. The capital is calm these days, so I don’t know exactly what I was expecting as I made my way down Mykhailivska street.

Tents still populate Maidan, with young and old lounging, talking and cooking in the May sunlight. I walked past sandbag barricades, and ones made of tyres painted in the blue and yellow of the Ukrainian flag. There were flags were everywhere — EU, American, British, and many more. I walked past the independence monument, juxtaposed against the new year tree, covered by protesters in posters, and yet more flags. Music was blaring out from the small stage facing these towering structures. The lyrics I couldn’t understand, apart from the cry of “Ukraina” in the chorus. I made my way past the Maidan press centre, towards a bridge which had a large banner emblazoned with names and faces hanging from it. The Hotel Ukraina behind me, I looked out over the square.

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

The only thing missing was the crowds. It felt like they had just taken a break — gone for lunch, to return at any moment. Perhaps I arrived with a naive “out of sight, out of mind”, mentality, subconsciously assuming that the square would to an extent have been cleared out. But Maidan seems to be, for now at least, a living monument to the profound change, and crisis, Ukraine is going through.

It was against this backdrop, and with the country’s general elections set for this Sunday, I travelled to Kiev to take part in the conference Ukraine: Thinking Together. The brainchild of Yale University history professor Timothy Snyder and the New Republic’s Leon Wieseltier, its purpose was “to meet Ukrainian counterparts, demonstrate solidarity, and carry out a public discussion about the meaning of Ukrainian pluralism for the future of Europe, Russia, and the world.” The guest list included academics like Bernard-Henri, Lévy Timothy Garton Ash and Ivan Krastev, and journalists like The New York Times’ Roger Cohen and The Atlantic’s David Frum. Former Swedish prime minister Carl Bildt also made an appearance at the welcome reception.

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

One could question what, if any, effect the discussions of a group of intellectuals might have on the very real crisis on the ground. Over the weekend, there were among other things, a Crimean Tartar journalist was detained in Simferopol, while the Ukrainian military arrested two Russian reporters. But Kiev-based journalist Maxim Eristavi told me, and tweeted, that it was “surreal” to have the “intellectual powerhouse of the West in one room in Kyiv”. If nothing else, organising a big-name gathering to talk about Ukraine, in Ukraine, makes a bold statement — and one likely to be heard all the way to Moscow.

A range of topics were tackled in five days of panel debates and public lectures. The Maidan protest was applauded, with Wieseltier in his opening remarks calling it “one of the primary sites of the modern struggle for democracy”. Carl Gershman, President of the National Endowment for Democracy, called Maidan a geopolitical move, but by a people rather than a government.

(Image: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

Bernard-Henri Lévy spoke of his recent visits to eastern Ukraine, explaining that while they might be fewer than in the Maidan, there are people in these areas who support a unified Ukraine. He contested what he believed to be the image presented in western media that people in the east are all separatists. While the point was made that flags, national symbols and the Maidan movement is not perceived as positively in all parts of the country as in Kiev, Constantin Sigov, professor at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla, argued that the Ukrainian crisis is first and foremost civil and political, not one of identity.

Russia’s foreign policy and Russian President Vladimir Putin were unsurprisingly recurring themes. “He has values. They are not our values, but they are values,” said François Heisbourg, chairman of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, talking on the panel of geopolitics after Crimea. Writer Paul Berman argued, in the same panel, that Putin is acting from a position of weakness, and fear that Russia is not stable. Others, meanwhile, were uncomfortable with the term geopolitics, saying it legitimises Putin’s world view.

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

Russia’s propaganda strategy was also a hot topic and elicited strong responses, with one audience member referring to it as a weapon of mass destruction. “Propaganda is the beginning of bloodshed, it precedes bloodshed,” said Alexandr Podrabinek, editor-in-chief of Prima information agency, on the panel discussing whether rights make us human. State-run news channel RT, formerly Russia Today, got several mentions. Academic Anton Shekhovtsov argued that RT gives space to democratic consensus in its coverage, but also to left-wing, far right and libertarian narratives, and even conspiracy theories. Because each is treated in roughly the same way, the democratic narrative becomes just one of many. He said this explains why RT appeals to some people in the west, but stressed that they’re pushing an overall Russian agenda.

Podrabinek, despite dubbing RT “hateful”, argued that while there might be a temptation to shut down views we don’t like, this is not a good way of confronting them. If we want freedom of expression, he said, we can’t do that. On a related note, Carl Gersham argued that while Ukraine needs to be supported economically and militarily, they also need support in modernising the media landscape, to foster internal dialogue.

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

And while the regime was criticised by speaker after speaker, ordinary Russians and their rights were not forgotten. Sergei Lukashevsky, director of the Sakharov Museum and Public Centre, put the support for Putin into the context of fear. When people see that the state is cracking down on human rights again, he argued, they make themselves fit in — go into survival-mode. While rights exist formally in Russia, he explained the practical situation through an old Soviet joke: “Do I have the right? Yes. Can I? No.”

In a weekend of intellectuals discussing how to solve a crisis, novelist and non-fiction writer Slavenka Drakulic gave a sobering lecture on the role of intellectuals in causing crises, specifically the Balkan wars. To be able wage war, to kill, you have to create an enemy and dehumanise it, she argued. Here is where academics, poets, journalists came in handy in former Yugoslavia — by preparing people psychologically for conflict, “using words almost like bullets”.

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

And this leads well into the final panel of the conference, on the role of history and memory in politics, the difference between official history and collective and personal memories of the people, and how especially the former can be manipulated. We’re arguably seeing that today already, with Timothy Snyder saying that with events in Ukraine, a European revolution is being contested even as it’s happening. The Russian Ministry of Education is already writing new chapter to explain Crimea, said acclaimed Ukrainian novelist Andrey Kurkov. “And Ukraine might have their version.”

After my trip to Maidan, I asked a Ukraine-based AP journalist what the future might bring for the square. There are only a specific type of people still there, she explained, and they might see how the elections go before they decide to stay or leave.

Or as Myroslav Marynovych, the founder of Amnesty International Ukraine, said during the conference — when there is democracy, there will be no need to go to Maidan.

This article was published on May 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

21 Jan 2014 | Asia and Pacific, Bangladesh, News and features

Election day in Bangladesh (Image: Md Manik/Demotix)

It is a story worthy of great theatre: the bitter rivalry between two women that is tearing apart a country.

Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia head the two main political parties of Bangladesh, and have swapped power back and forth for the last 20 years.

The relationship between the two “battling begums” has come under international scrutiny recently, after Bangladesh suffered the most violent election in its short history. More than 100 people died during the campaign, with the country disrupted by strikes, blockades, and violent clashes between police and opposition supporters.

The controversy started well before the country went to the polls on 5 January. Since 1996, Bangladesh has held elections under a neutral caretaker government. In 2010, Hasina’s Awami League party, buoyed by a strong parliamentary majority, decided to abolish the provision. The opposition, Zia’s Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) took issue with this, saying that a fair election could not be guaranteed without a neutral body overseeing it. The Awami League would not set up a caretaker government. The BNP boycotted the election.

Hasina decided to go ahead with the poll. Inevitably, her party – unopposed in 153 of the country’s 300 constituencies – won. But, equally inevitably, the validity of a contest in which there was only one real option has been questioned. The election result was also undermined by an unusually low turnout, with the government putting the figure at under 40 per cent and others reporting far less than that.

This was not just to do with voters choosing not to vote, but with a systematic campaign of intimidation and violence by supporters of the opposition BNP. Enforcing blockades, strikes, and boycotts, supporters of the BNP and their allies, the Jamaat-e-Islami, petrol bombed buses carrying workers, and set fire to shops that had opened in defiance of the strikes.

“The violence perpetrated against people who have not complied with the opposition call is a criminal act and it is the responsibility of the government to bring the attackers to justice,” says Abbas Faiz, Bangladesh researcher for Amnesty International. “But the majority of people who died during the two months of elections died from gunshot wounds. There is a strong possibility the police may have used excessive force.” Amnesty is calling for immediate investigations to identify the perpetrators of attacks, and to establish whether the force used by police was lawful. In a statement, UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon called on “all sides to exercise restraint and ensure first and foremost a peaceful and conducive environment, where people can maintain their right to assembly and expression.”

Elections in Bangladesh tend to be big public events, with people getting up early to join famously long queues and proudly displaying their ink stained fingers. Yet people in the capital Dhaka during this year’s election described an eerie calm. Voting took place in just nine of 20 seats in the city. There were vicious attacks on the country’s Hindu minority, who make up around 10 per cent of the population and tend to support the Awami League.

The consensus seems to be that both of the main parties are equally culpable for the farce that the election has descended into. An editorial in the country’s Daily Star newspaper said that the Awami League had won “a predictable and hollow victory, which gives it neither a mandate nor an ethical standing to govern effectively”. Its verdict on Zia and her associates was no better: “Political parties have the right to boycott elections. But what is unacceptable is using violence and intimidation to thwart an election.”

The election chaos comes after a year of ugly political violence in Bangladesh: around 500 people were killed in political clashes during 2013, making it one of the most violent years since independence in 1971. This began with a mass popular movement against religious fundamentalism. Named the Shahbag movement, after the area of Dhaka where it began, the protests swiftly triggered a backlash from the religious right and their supporters. Much of this polarisation – between secularists and Islamists – had been precipitated by the government’s war crimes tribunal. Prosecuting people for crimes committed during the war of independence in 1971, the tribunal has reopened old tensions. Islamists claim it is being used to shut down the opposition, while secularists argue that the sentences (which include the death penalty) are not harsh enough.

Now, several weeks after the election, the political system remains in crisis. Zia is effectively under house arrest, while Hasina’s victory is seen across the board as empty. International and domestic observers alike say that the only way forward is for the two women to sit down together and hammer out a compromise. With early elections expected within the next 18 months, and with political uncertainty and violence continuing, this is ever more pressing.

This article was published on 21 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

2 Sep 2013 | Belarus, News and features

For the first time since the 2010 presidential election Belarusian independent journalists can catch their breath. In March the criminal case against Andrzej Poczobut, a journalist accused of libel against the president, was dropped. ARCHE magazine, which was close to being shut down was finally re-registered by the Ministry of Information in May. OSCE Representative for Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatovic was allowed to enter the country in June, and authorities even met with her. Following her visit charges against Anton Suriapin for posting pictures of the famous Teddy Bear pictures, were dropped. Award-winning journalist Iryna Khalip has reached the end of her two-year sentence.

For the first time since the 2010 presidential election Belarusian independent journalists can catch their breath. In March the criminal case against Andrzej Poczobut, a journalist accused of libel against the president, was dropped. ARCHE magazine, which was close to being shut down was finally re-registered by the Ministry of Information in May. OSCE Representative for Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatovic was allowed to enter the country in June, and authorities even met with her. Following her visit charges against Anton Suriapin for posting pictures of the famous Teddy Bear pictures, were dropped. Award-winning journalist Iryna Khalip has reached the end of her two-year sentence.

On the other hand, we should not be deceived by these positive developments. Negotiations with Mijatović did not prevent Belarusian authorities from seizing a whole print run of Nash Dom newspaper, accusing journalist Alena Sciapanava of cooperation with foreign media without a relevant accreditation, or detaining a number of reporters covering a street action by opposition activist in July.

So, is there a thaw for Belarusian media? Can further changes be expected?

One step forward after two steps back

Belarus is ranked 157th in Reporters Without Borders’ 2013 World Press Freedom Index, rising 11 places compared with their 2011/2012 rating. But this only means the country has restored the situation to where it had been before the severe clampdown on free media and civil society in December 2010. Independent journalists and online activists still run risks.

“The authorities have made a small step forward after they made two huge leaps back. The situation improved a little if we compare it with the one we had after the 2010 presidential election. But on a systemic level neither media-related legislation, nor its implementation have changed,” says Andrei Bastunets, a media lawyer and a vice chairman of the Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ).

The positive developments are welcome – but history suggests they are not irreversible. In 2008-2009 similar period of “liberalisation” was marked with two big conferences in Minsk co-organised by the Belarusian authorities with the office of OSCE Representative for Freedom of the Media. There, the decision was made to return two national independent newspapers, Narodnaya Volia and Nasha Niva, to the wide reaching state run systems of press distribution. But the ‘good times’ turned into a renewed period of repression after 2010.

Sviatlana Kalinkina, chief editor of Narodnaya Volia, says life is easier for the publication now than it was five years ago when it had to be printed in Russia and was not allowed to be sold at newsstands or via subscription catalogues in Belarus.

“The approach of the authorities is to make the situation worse, then to return it to where it was and thus claim there have been improvements and ‘democratisation’. But in fact even after we were allowed to be printed and distributed in Belarus we were not able to come back to where we used to be. Narodnaya Volia used to be a daily, now we publish our newspaper twice a week and cannot get a permission to be printed even three times a week. Printing houses and distribution networks keep telling us it is impossible, although it is obvious these are just lame excuses. These problems are clearly orchestrated by the authorities,” says Sviatlana Kalinkina.

It is difficult for a journalist of an independent newspaper to receive a comment from state officials; they are afraid to talk to non-state press.

According to Yanina Melnikava, the editor of the online publication Mediakritika.by, the situation inevitably affects the quality of work of Belarusian journalists.

“One the one hand it makes a journalist’s work really hard. But working in the conditions of an ‘information war’ leads to a ‘barricade mind-set’ that can be used to justify mistakes and lack of professionalism,” says the editor.

Screws to be tighten again before elections

Sviatlana Kalinkina of Narodnaya Volia does not think conditions for her newspaper will significantly improve in the nearest future, because the next presidential election is scheduled for 2015.

“Political campaigns are not the best time for journalists in Belarus. People are getting more interested in independent news which makes authorities start to panic, resulting in more oppression,” Sviatlana Kalinkina says.

So why would the government allow some minor improvements of the situation? The answer is simple – just to have some “room for manoeuvre” when the screws are to be tightened again.

“The closer elections are, the more we are likely to feel freedom and democratic change is possible. But this is just an illusion. The reality is different. The authorities see election campaigns as a threat to their power and they are ready to protect their power whatever it takes,” says Yanina Melnikava.

Not ready for the first step

During her press conference in Minsk on 5 June, Dunja Mijatović said time had come for serious change in the freedom of expression situation in Belarus. She called on journalists to “work with the authorities and bother them in order to let the government of the country know about the importance of laws for development, not for oppression of the media.”

“But the real change requires a totally different relationship between the authorities and the media. Such change of an attitude should take place on an ideological level, as well as on economic and legal levels”, Yanina Melnikava admits, adding that she sees no signs of such changes at the moment.

Andre Bastunets suggests there should be a road map the authorities can keep to in order to liberalise the media field. The first step would be ceasing of economic discrimination of independent media: all non-state newspapers should be allowed back on to state-run distribution systems, restrictions of circulations and advertising in them should be lifted.

“About half of independent newspapers face problems like these now. And there is no need to change the law to solve the problem – on the contrary, we just need to implement the law,” says BAJ vice chairman.

The second step would be to ensure access to information for all journalists. The restriction to work without a special accreditation for reporters of foreign media should be lifted. The third one is to stop differentiating between state and non-state media at all.

“I am sure there should be no state-owned media in a democratic country except for bulletins with legal acts adopted by state bodies. All media should be private or public,” says Andrei Bastunets.

However, the authorities of the country show no signs they are ready event to make that first step, which means the current not-so-bad situation is always under threat of a set-back.