25 Feb 2025 | Asia and Pacific, Australia, News

Petrina Harley likens direct action to giving birth.

“My body knew it had a job to do, so I got on and focused on my inner strength,” the 53-year-old mother of two told Index via phone from Perth. “I find it really empowering.”

Harley is a climate activist of eight years facing trial in June for repeatedly blocking entry to Australia’s biggest gas hub to be built in a decade, a AU$16.5 billion ($10.35 billion) project in the Pilbara on the Burrup Peninsula of Western Australia (WA) by sector giant Woodside.

It may come as a surprise to some, but not to Harley, that new research from the University of Bristol released in December showed that Australia is now the world’s top country for arresting climate and environmental protesters.

“I’ve been arrested four times now,” said Harley. Alarmingly, arrest is now a common response in 20% of all climate and environmental protests in Australia, with the international average being 6.3%.

This is also part of a broader crackdown in the country, where new measures in the state of Victoria purportedly aimed at tackling recent cases of anti-Semitism could be used to target climate protesters, human rights lawyers have now warned.

There’s particular concern that a potential ban on “lock on” devices such as glue, chains or locks, could be used to take aim at environmental campaigners. Similar laws have been announced in New South Wales (NSW).

“The arrests [in Australia] are one dimension of criminalisation,” said Oscar Berglund, senior lecturer in International Public and Social Policy in the School for Policy Studies at the University of Bristol.

“There have also been multiple new anti-protest laws passed. What we are seeing currently is an intensifying criminalisation of protest in both democratic countries and less democratic countries.”

Harley, who began protesting after she had children, said that she had tried “everything under the sun” including running for the Senate in the lower house with the Socialist Alliance party, holding weekly stalls in town and gathering petitions, before she took part in two blockades in WA.

In the first one, in November 2021, Harley and another Scarborough Gas Action Alliance activist, Elizabeth Burrow, used a caravan to obstruct entry to the Woodside project. The activists bonded their arms into a concrete drum inside the vehicle. Harley was “locked on” for 16 hours. When she refused to move, she was arrested in the caravan and after being taken to hospital for injuries locked up overnight and charged. Harley said it was “complete overreach” by police.

The pair pleaded not guilty and used an emergency defence – normally reserved for cases like murder – arguing that the activities of Woodside are directly putting lives at risk. In 2023 they were found guilty by a magistrate’s court in Karratha in the Pilbara region of failing to obey an order given by an officer, obstructing public officers, and unreasonably obstructing or preventing the free passage on a path or carriageway.

They received a six-month community-based order, with a requirement to complete 100 hours of community service and were also handed a $600 fine each. Police initially sought more than $33,000 in compensation from the activists for removing them from the caravan, but this application was later dismissed.

Last July, Harley and another activist, Emma, a high school student, used a car and a boat to block the only access road to the same project, in a bid to stop its operations. Harley was “locked on” for 12 hours. She is now facing three obstruction charges over this.

At her trial in Perth in June, she will again plead not guilty using the extraordinary emergency defence.

“I’m very excited, I’ve got a really ethical lawyer who’s keen to test the case because it would be a precedent,” Harley said. “People have tried it before, but no one’s actually won. I’ve got some very high-profile witnesses to testify.”

David Mejia-Canales is a Sydney-based senior human rights lawyer at Australian group Human Rights Law Centre (HRLC). He said that an analysis of two decades’ worth of anti-protest legislation in Australia from 2003 onwards found that out of 49 pieces of legislation introduced, most target environmental protesters in the streets, at mines or logging sites. But laws are broad and vague despite peaceful protest being protected under international law.

“In Australia you just have to look out the window to notice that the climate crisis is getting worse and the thing that our governments are appearing to do is to jail climate protesters instead of actually doing anything that is meaningful and quick and long lasting about this,” said Mejia-Canales.

He said HRLC wasn’t aware of any activists in Australia who have been acquitted on an emergency defence. But framing the necessity defence (breaking the law to prevent greater harm) as an “extraordinary emergency defence” could allow protesters to use the growing acceptance of climate change as an emergency that requires urgent attention, he said.

However, just last week a climate activist in Melbourne was told that he cannot rely on evidence from climate experts following charges relating to an Extinction Rebellion protest.

Mejia-Canales said that Australia urgently needs a Human Rights Act, which could be crucial for climate activists, reinforcing arguments that their actions seek to uphold fundamental rights rather than merely disrupt public order.

A WA government spokesperson told Index: “Everyone is entitled to protest peacefully in WA, however police will respond to violent or threatening behaviour.”

Index approached the minister for climate change and energy for comment, but did not receive a reply.

Woodside said that it supported respectful debate. But it said acts intended to threaten, harm, intimidate or disrupt employees, their families or any other member of the community going about their daily lives “should be met with the full force of the law”.

Read more: UK journalists fall victim to new police tactics

4 Nov 2022 | Egypt, Middle East and North Africa, News

The 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference, or COP27 as it is better known, opens this Sunday, 6 November, in the Egyptian Red Sea resort of Sharm El Sheikh.

As has become customary, COP27 will become the focus of protest. Yet not all protests at COP27 will be about the environment.

One protester at the event, Sanaa Seif, says that the world leaders attending will have “blood on their hands” if they do not secure the release of her brother, the British-Egyptian writer and activist Alaa Abd El-Fattah. Abd El-Fattah is a pro-democracy activist and founder, with his wife Manal Hassan, of the Arabic blog aggregator Manalaa. He has been held in the country’s prisons on and off for nine years for his part in the 25 January protests that rocked the country in 2011.

In 2013, the writer was jailed by the government of Egypt’s military ruler Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and has been in prison most of the time since where he has been both tortured and offered only limited communication with his family.

In order to bring attention to his plight, Abd El-Fattah went on a partial hunger strike on 2 April this year, limiting his intake to just 100 calories a day, sipping tea with a spoonful of honey. After six months on hunger strike, his body is seriously weakened and his health is in a precarious state. Four days ago, he stopped even that meagre daily allowance and is now taking only water.

On the opening day of COP27, he will stop even that.

Since 18 October, Sanaa and her sister Mona, have been holding a sit-in as part of their Free Alaa campaign outside the UK’s Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office to draw the attention of incoming Foreign Secretary James Cleverly to their brother’s plight.

On Wednesday this week, Cleverly finally spoke to the pair and vowed that the Government would “continue to work tirelessly for his release”.

In a Facebook post, the sisters said: “We were so relieved to finally get to speak to James Cleverly and hear his assurance that Alaa’s safe release is top priority. I hope this translates to tangible action that actually saves Alaa before it is too late.”

At a press conference on the street outside the FCDO the following day, Sanaa said: “Alaa will escalate his hunger strike as he stops taking water as world leaders head to Egypt to attend COP27. I want to tell these officials that if you don’t save him you will have blood on your hands. I want to call on Rishi Sunak – you are going to be in the same land as a British person dying and if you don’t show that you care then it will be interpreted as a green light to kill him.”

Sanaa’s sister Mona added: “Alaa is in a very critical state but he is not desperate to die. These are the actions of a man who is desperate to end this ordeal he has been sucked into for nine years and desperate to be reunited with his family.”

The British-Egyptian writer and activist Alaa Abd El-Fattah in happier times with his wife and baby son Khalid

Speaking to Index, Mona said: “In the eyes of the Egyptian regime Alaa is one of the symbols of 25 January [2011 revolution] and therefore one of those calling for an end to the leadership of the military regime. In some people’s minds he is a British national. For others he is a writer, or an activist. Most importantly, he is an amazing brother and a son. And most importantly of all what seems to be forgotten is that he is a father to a 10-year-old, Khalid.”

She added: “Khalid and his father have a unique and extraordinary relationship. Khalid is on the autistic spectrum and is non-verbal. We found out his diagnosis back in 2014 when Alaa was serving his first five sentences. Alaa was briefly released in 2019, although he had to spend every night in a police cell, and Alaa and Khalid formed an amazingly strong bond. We were worried about how Khalid would receive his father because he was not used to him in his life. We were honestly surprised. He and Khalid bonded immediately. He flourished under Alaa’s presence and Khalid’s doctors and teachers all noted a massive difference.”

“When Alaa was taken again in September 2019, the one hit the hardest was Khalid. When Alaa appeared before the state security prosecution, Khalid was angry with his father for disappearing. Since then, it has been particularly difficult to sustain Alaa’s presence in Khalid’s life. A very big part of why Alaa has taken such extreme measures is that he feels Khalid has been orphaned.”

Mona and family will hold a candlelit vigil for Alaa outside Number 10 Downing Street at 4pm on 6 November. Meanwhile, Sanaa will fly out to Egypt to take part in an event with the German climate envoy, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International at COP27 next Tuesday.

“This will serve as an embarrassing reminder to everyone,” Sanaa said.

Mona has another message to the leaders attending COP27. In another Facebook post this week, she wrote the following.

“Regardless of how it ends Alaa has already won this battle. If he makes it out alive and joins us, his family, in safety. Then he would have done it using only his body and words. If he doesn’t make it and dies in prison, his body will tell the whole world what a bunch of liars you all are, ruthless inhumane creatures that should not be trusted with one plant let alone people and the future of this planet.

31 Aug 2022 | FEATURED: Martin Bright, News, Russia

Mikhail Gorbachev in 2008. Photo: European Parliament, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

In 2000 Mikhail Gorbachev wrote a short piece for Index on Censorship about the dangers to free expression in 21st century Russia. It followed raids carried out by masked, armed police on the offices of the Media-MOST consortium, then one of the most powerful media organisations in Russia. It was a show of force by the incoming president, Vladimir Putin, and a chilling sign of things to come.

The article, entitled Citizens’ Watch, expressed the best of the former President’s instincts in support of democracy and freedom: “Without a free press people don’t have a voice. They can be used as the authorities see fit; they can be manipulated”.

It was also prophetic in its concerns that the Russian people were sleepwalking into an authoritarian disaster: “I’m… worried and dispirited by the apathy of the public. The journalists are having to defend themselves on their own. It’s time we understood we shall never be a democratic state until we have learned to be citizens.”

He concluded: “It is not easy to live as a free man; without democratic institutions and rules, freedom often becomes its opposite.”

But the piece also demonstrates Gorbachev’s fatal weakness. As a good man with good intentions, he was too willing to give those with bad intentions (such as Vladimir Putin) the benefit of the doubt. Musing on who might be ultimately responsible for the crackdown, he wrote: “I find it hard to believe that raids like these can take place with the president’s knowledge. If, indeed, it is with his knowledge, I personally feel very disappointed.”

Disappointment defined Mikhail Gorbachev. As the last leader of the Soviet Union, he was quite possibly the most influential political figure of the post-war period, but from the moment the Berlin Wall fell, his life was marked with a series of disappointments. He had hoped the break-up of the Soviet Union would lead to democratic transformation and the introduction of a market economy with social safeguards. In many countries of the former Eastern bloc, this was indeed the case, but he also witnessed the rise of tyranny and corruption in many of the former Soviet republics. In his beloved Russia itself, he saw his liberal economic reforms hijacked first by the oligarchs and then by the state itself. This man of peace, whose childhood had driven him towards dialogue with the West, stood by as his country descended into an increasingly aggressive foreign policy with wars in Chechnya, Georgia, Syria and latterly in Ukraine. History will judge him harshly for his support of the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, although in his mind it was consistent with his lifelong support for national self-determination.

But possibly his greatest disappointment was what he saw as the catastrophic failure of world leaders to deal with the environmental crisis. In an interview with the Russian publication Dos’e na Tesnzuru reprinted in this magazine in 1998 he noted that “ecology” sprang to the top of the agenda in Russia thanks to his policy of glasnost (openness). As a result, 1,300 polluting enterprises were closed. It was his dream to establish a global environmental organisation to address the combined challenges of security poverty and environmental destruction and following the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 he established Green Cross International in Geneva.

His words in Index sounded an important warning: “Everyone can see that the forests are retreating, rivers becoming polluted. The reasons are obvious – people rule the earth, but they are not looking after it, only making demands: give me cotton, give me wood, give, give, give. We have to manage things differently.”

The end of the Cold War was Gorbachev’s greatest legacy and he knew that the freedoms he helped establish were built on the work done by the dissident intellectuals that came before him. He also knew that complacency was not an option.

A quarter of a century ago he told Dos’e na Tesnuru (which means Index on Censorship in Russian): “I am not a pessimist. All over the world the last dictators are leaving the political scene; attempts to impose dictatorship are ridiculous. Only one thing can protect us from such attempts – freedom of speech. That’s why any defence of freedom of speech is so important. Without it we could find ourselves once again caught in the trap.” His prediction of the demise of dictatorships was perhaps premature, but he was never wrong about the antidote.

29 Sep 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Editions, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021

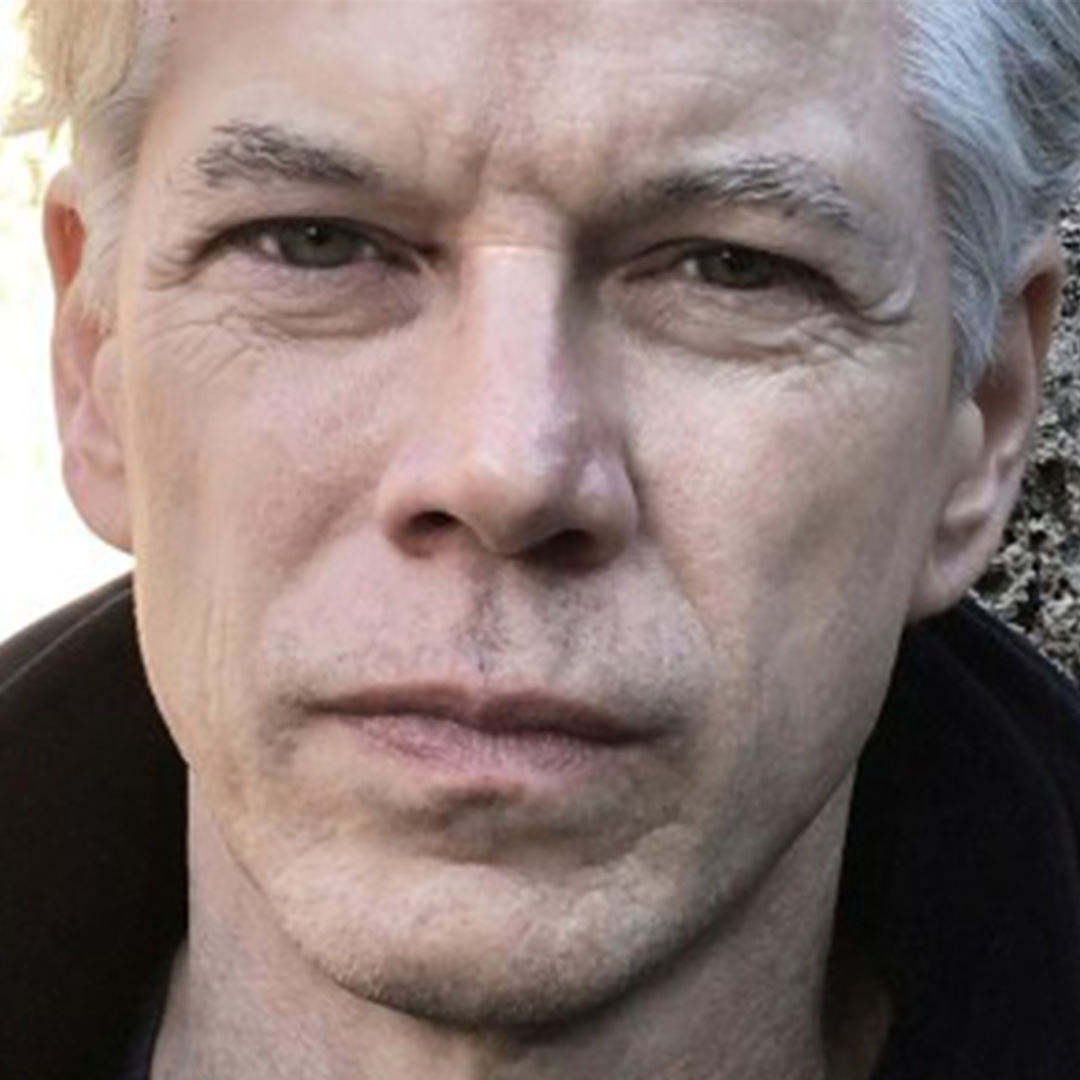

Journalist

John Sweeney is a writer and journalist who has investigated Scientology and Russian interference in the US elections. He is the host of the Hunting Ghislaine podcast.

Activist and producer

Kelly Duda is an activist and producer and director of the documentary Factor 8: The Arkansas Prison Blood Scandal.