24 Jul 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

People gather in support of the Cumhuriyet defendants as the trial got underway.

Executives and columnists of Turkey’s critical Cumhuriyet daily go on trial this week, beginning Monday 24 July. The indictment seeks prison sentences for the defendants varying between 7.5 to 43 years. The charges for those on the board of the Cumhuriyet Foundation, which oversees the newspaper, include “abuse of power in office,” but all are accused of “supporting terrorist organisations” mainly through changes that have occurred in the paper’s editorial policy following the election of a new board to the foundation in 2013.

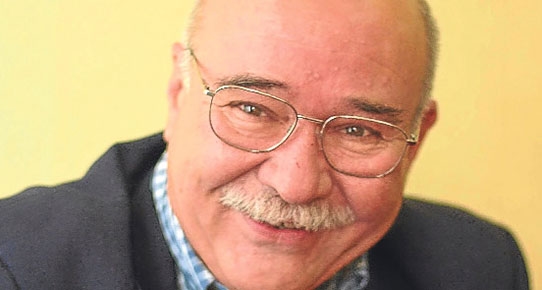

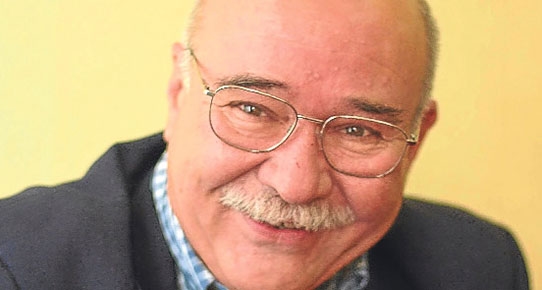

The prosecution’s claims are supported by views of several media experts — most of whom are former executives or employees terminated from various positions, according to Aydın Engin, a Cumhuriyet columnist who is also a defendant in the case although he was released pending trial due to his advanced age.

As Engin says “Cumhuriyet changed its editorial policy: this is the essence of the indictment.”

Indeed, the 435-page long document laments, page after page, that Cumhuriyet ditched its traditional, Kemalist, unyieldingly secularist and statist editorial policy and became a more open-minded newspaper.

The prosecutor states that by altering its editorial stance, the newspaper became a supporter of the so-called Fethullahist Terrorist Organization (FETÖ/PYD) — the name Turkish authorities give to the Fethullah Gülen network, which they say was behind last year’s coup attempt –, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK/KCK) and the Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (DHKP-C); three organizations with unrelated if not completely opposing worldviews.

“A newspaper changing its editorial policy cannot possibly be the subject of an indictment,” Engin says.

But did Cumhuriyet really change its editorial policy to legitimise the actions of FETÖ/PDY; PKK/KCK and DHKP/C as the prosecutor claims? “Every newspaper makes editorial policy changes as life unfolds. Cumhuriyet also did this. The paper caught up with the general tendencies in society such as increasing demand for freedoms, human rights and a stronger civil society.”

Engin says many of the witnesses who have testified against the Cumhuriyet journalists have been discredited as media professionals. “When I told the prosecutor that I will not respond to claims by people who have no reputation as journalists, he showed me a post by Professor Halil Berktay, who tweeted that ‘Cumhruiyet has become FETÖ’s media outlet.’ The prosecutor said, ‘This from a professor. Who are you to deny its validity?’

Engin: old and tired

Will any of the Cumhuriyet journalists be released at the end of this week? “I don’t even want to being to make any assumptions. This is not a legal trial; it is entirely political,” Engin replies, adding: “I strongly need them, personally, because I am 76 and tired,” says the energetic-looking journalist, who, as he speaks, is interrupted by someone asking him to sign a financial document. “See, I don’t even know what I just signed, I don’t know anything about these things.”

According to Engin, because those imprisoned are the key people to the newspaper’s operations, Cumhuriyet is now “half-paralyzed.”

But really, who are those in prison?

“Our brightest colleagues are in the can. Akın Atalay, is our CEO and I am a first-hand witness of how he has managed to keep the newspaper on its feet. Murat Sabuncu, he is perhaps one of the two or three finest journalists I know who can smell the news. He is publicly unheard of but Önder Çelik: he has been with Cumhuriyet for 35 years, he is the finest expert at things such as analyzing circulation reports, maintaining relations with printing houses; following paper prices..”

“I really need them to get out, but I don’t want to be dreaming.”[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Turkey” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:30|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fmappingmediafreedom.org%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship monitors press freedom in Turkey and 41 other European area nations.

As of 24/07/2017, there were 496 verified reports of media freedom violations associated with Turkey in the Mapping Media Freedom database.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”94623″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://mappingmediafreedom.org/#/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]The journalists on trial for the first time on 24 – 28 July:

Akın Atalay (Cumhuriyet Foundation Executive President; imprisoned since Nov. 12, 2016): Facing 11 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust”

Akın Atalay (Cumhuriyet Foundation Executive President; imprisoned since Nov. 12, 2016): Facing 11 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust”

Atalay graduated from İstanbul University Law School in 1985. He has acted as the founding member of a number of civil society organisations and his academic studies on press freedom and the law have appeared in a large number of academic journals and newspapers. Since 1993, he has represented Cumhuriyet columnists and reporters as legal counsel. Currently, he is the newspaper’s executive president.

Bülent Utku (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board Member, attorney representing Cumhuriyet; imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust”

Bülent Utku (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board Member, attorney representing Cumhuriyet; imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust”

Utku has worked as an attorney for 33 years. Since 1993, he has worked as a lawyer for Cumhuriyet columnists and journalists. He is also a member of the Cumhuriyet Foundation’s Board of Directors.

Murat Sabuncu (editor-in-chief, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” [Turkish Penal Code (TCK) Article 314/2]

Murat Sabuncu (editor-in-chief, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” [Turkish Penal Code (TCK) Article 314/2]

Sabuncu has been a journalist for 20 years. He started working at Cumhuriyet in 2014 as the newsroom coordinator. In July 2016, he took the helm as editor-in-chief.

Kadri Gürsel (publications advisor, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

Kadri Gürsel (publications advisor, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

A journalist of 28 years, Gürsel started writing columns in Cumhuriyet in May 2016. He assumed the position of publications advisor for the newspaper in September 2016.

Güray Öz (board member, news ombudsman, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 8.5 to 22 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”

Güray Öz (board member, news ombudsman, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 8.5 to 22 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”

Öz has been a journalist for 21 years. He has worked at Cumhuriyet since 2006. He is a columnist for the newspaper and has been its ombudsman since 2013. Öz is also on the board of directors of the Cumhuriyet Foundation.

Önder Çelik (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and four counts of “abuse of power in office”

Önder Çelik (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and four counts of “abuse of power in office”

Önder Çelik has been a newspaper administrator for 35 years. He has worked as the print coordinator for the newspaper between 1981 – 1998. He returned to the same position in 2002 after a hiatus. He has been an executive board member since 2014 as well as a board member of the foundation.

Turhan Günay (editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet’s book supplement, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 8.5 to 22 years for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”

Turhan Günay (editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet’s book supplement, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 8.5 to 22 years for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”

A journalist for 48 years, Günay has been with Cumhuriyet since 1987. For the past 25 years, he has worked as the chief editor for Cumhuriyet’s literary supplement, the country’s longest running weekly publication on books. The indictment insists he is a board member of the foundation; although he isn’t; a fact he reiterated in his testimony to the prosecutor.

Musa Kart

Musa Kart (Cartoonist, board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016) Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust”

Musa Kart, one of Turkey’s most renowned cartoonists, has been drawing political cartoons for 33 years. He has been a Cumhuriyet journalist since 1985. For the past six years, Kart has drawn the front-page cartoons for Cumhuriyet.

Hakan Karasinir (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Hakan Karasinir (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Hakan Karasinir has been a journalist for 34 years. He has been with Cumhuriyet for 34 years. In the past he has held various editorial positions, including serving as the newspaper’s managing editor between 1994 and 2014. Since 2014, he has also written columns in the newspaper.

Mustafa Kemal Güngör (attorney, board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”; two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Mustafa Kemal Güngör (attorney, board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”; two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Mustafa Kemal Güngör has been a lawyer for 31 years. He has defended Cumhuriyet journalists and columnists in court since 2013.

Can Dundar

Can Dündar (former editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet, currently resides abroad). Facing 7.5 to 15 years for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

Perhaps the most internationally famous of all Cumhuriyet defendants, Can Dündar was the editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet until August 2016. He was arrested in November 2015 after Cumhuriyet published footage suggesting that the Turkish government sent weapons to armed jihadi groups in Syria. He was released in February 2016, a few months after which he moved to Germany where he currently resides.

Orhan Erinç (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board President, columnist). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member” ; four counts of “abuse of power in office”

Orhan Erinç (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board President, columnist). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member” ; four counts of “abuse of power in office”

Veteran journalist Orhan Erinç, who worked for Cumhuriyet as a young reporter, returned to the newspaper in 1993 as its publications advisor. For nearly half a decade, Erinç also held the position of vice president at Turkish Journalists’ Association. He is also a columnist for Cumhuriyet.

Aydın Engin (columnist, released under judicial control measures). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”

Aydın Engin (columnist, released under judicial control measures). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”

Cumhuriyet columnist Aydın Engin has been a journalist since 1969. He has participated in the founding process for many news outlets, including Turkey’s Birgün daily. He worked as a columnist and reporter for Cumhuriyet between 1992 and 2002. He returned to the newspaper in 2015.

Hikmet Çetinkaya (columnist, board member, released under judicial control). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”; two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Hikmet Çetinkaya (columnist, board member, released under judicial control). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”; two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Çetinkaya has been with Cumhuriyet for three decades. In the past, the columnist worked as the İzmir Bureau Chief of the newspaper. He was also tried in 2015 along with Cumhuriyet columnist Ceyda Karan for reprinting the Charlie Hebdo cartoons in his column.

Ahmet Şık (Correspondent, imprisoned since Dec. 30, 2016). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

Ahmet Şık (Correspondent, imprisoned since Dec. 30, 2016). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

No stranger to Turkish prisons, Ahmet Şık worked as a reporter for Cumhuriyret, Evrensel, Yeni Yüzyıl, Nokta and Reuters between 1991 and 2007. He remained in prison for a year in 2011 in an investigation about a shady gang called Ergenekon, believed to be nested within Turkey’s state hierarchy. He is known as one of the most vocal critics of the Fethullah Gülen network.

İlhan Tanır (former Washington correspondent, resides abroad). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

İlhan Tanır (former Washington correspondent, resides abroad). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

İlhan Tanır previously reported from Washington for Cumhuriyet. His reports and analyses have appeared in many national and international publications. He currently resides in the United States.

Bülent Yener (Finance Manager). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”

Bülent Yener (Finance Manager). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”

A former financial affairs manager with Cumhuriyet, Bülent Yener was released after one day in custody.

Günseli Özaltay (Accounting Manager). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”

Günseli Özaltay, the newspaper’s accounting manager, was released after one day in custody.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1500894514864-6349d62e-4ed7-3″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

6 Jun 2017 | Academic Freedom, Mapping Media Freedom, News, Turkey

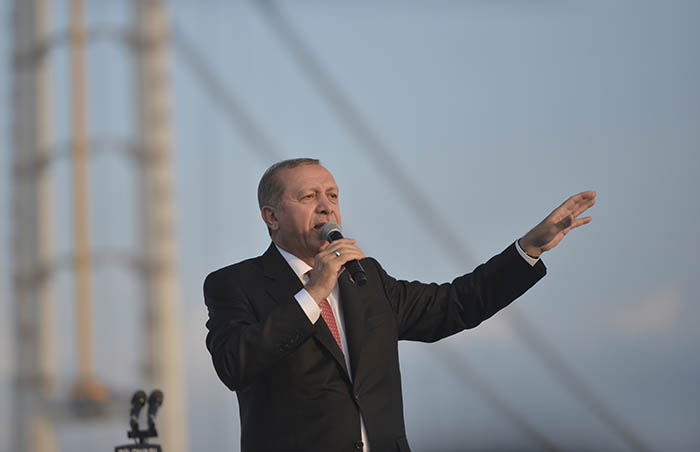

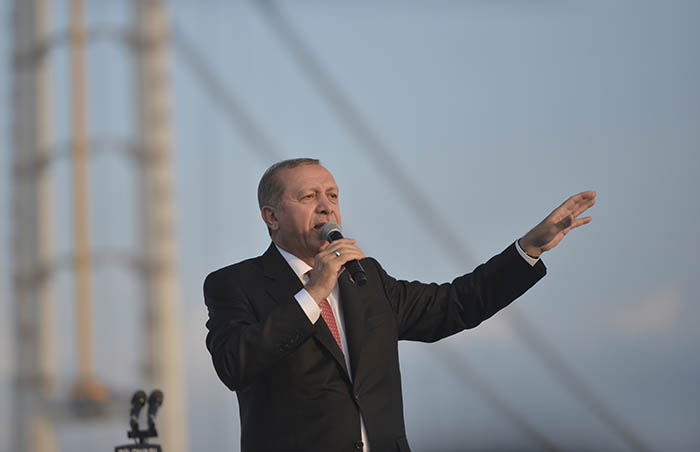

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”91204″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Turkey’s authoritarian shift has been unmistakable this past year. Following the coup attempt in July 2016, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s purge of state institutions has led to mass dismissals, including over 8,000 academics. Similarly, over 2,000 schools, dormitories and universities have now been shut down, causing great concern for Turkish education.

Nuriye Gulmen, a professor of literature, and Semih Ozakca, a primary school teacher, were both fired following the issuing of emergency decree 675 by Erdogan’s government. Shortly afterwards the pair joined forces demanding that academics across Turkey get their jobs back. Since they began protesting over six months ago with the slogan “I want my job back”, Gulmen and Ozakca have been detained by Turkish authorities over 30 times, most recently on 22 May. It is being reported that they will be tried for “membership of a terror organisation”.

The pair embarked on a hunger strike on 9 March 2017, which is now in its 90th day. While their story has now gained much international attention, they have little recognition from their own government.

“Amid a nationwide crackdown on freedom of expression, a hunger strike is the form Nuriye and Semih have chosen to protest the dire situation faced by academics in Turkey,” Index on Censorship’s head of advocacy Melody Patry said. “Index calls for their immediate release and for all charges against them to be dropped.”

Due to the massive number of arrests of journalists, academics and others within the last year, there is a serious backlog in the Turkish courts which means it could be a year from now before their case is even heard.

After protesting in various forms, from collecting signatures, distributing flyers and going door to door to share their story, Gulmen and Ozakca found little success. Instead, they were continuously detained by authorities before being released soon after.

Throughout their current hunger strike, there has been a significant deterioration in their health, and Ozakca has lost over 37 pounds from a diet consisting of salt water and sugar solutions with a single B vitamin. Gulmen says she experienced heartburn and a drastic drop in blood pressure which then lead to aching muscles, difficulty moving, loss of tissue, sensitivity to light and trouble concentrating. Eventually, the pair experienced severe difficulty walking as well as muscle atrophy, and are now both confined to wheelchairs.

This has not, however, hindered their hope of victory in their battle with the government. In a video released earlier in May, Gulmen stated that the solidarity and support of the public was making her feel better and that the pair’s “resistance is continuing and we will not stop until we gain our rights again.”

Similarly, they stated their latest detention will not halt their hunger strike, as they promised to continue it in prison.

The solidarity and support, which they have expressed thanks for, has come in many forms. David Harvey, professor of anthropology and geography at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, released a video providing support in which he said: “I want to express my solidarity with my friends and colleagues who are on a hunger strike in Turkey. I think that the sooner we enter a democratic process in Turkey, the better. I support all the actions made for this purpose with all my heart.” Turkish singer, Sezen Aksu, has also offered support and called on the Turkish government to take action and “listen to their voices”

Over 145,000 public workers have been fired since the failed coup, resulting in an array of protests and public demonstrations by activists and the general public throughout the world. Many Turkish public workers have protested on their own behalf in an attempt to regain their jobs and draw attention to the government crackdown.

Many, including Efe Sevin, a Turkish post-doctoral researcher at the University of Fribourg, believe the coup has become an excuse for Erdogan to do anything he wants, including stamping out opponents and potential opponents by labelling them as enemies of the state and members of terrorist organisations.

“Erdogan is very dismissive of intellectual capital and opposition,” Sevin added. “The only reason one may oppose him is if they have some secret/hidden agenda to overthrow the government or they are terrorists or they are supported by foreign powers to do so.”

Thinking about the overall impacts of these dismissals on Turkish academia depresses Sevin both personally and professionally depressed. “Especially with the most recent decrees that dismissed peace petition signatories that had no known ties with Gulen, I think ‘will there be a new decree with my name on it?’ is a fear all Turkish faculty members share.”

“Even though it is becoming more and more difficult to defend academic freedom under the current regime, we should not pretend that Erdogan took over an academic freedom utopia,” Sevin said. “Especially after the coup in 1980 and the establishment of Council on Higher Education, academic freedom was at best questionable in Turkey.”

Similarly to Gulmen and Ozakca, one of Turkey’s most prominent academic reformers, Kemal Guruz, was sentenced to thirteen years and eleven months in prison by a criminal court in Turkey on 5 August 2013. His ordeal began in 2009 when he was accused of being a member of a secret terrorist organisation and ”reached a climax” in 2012 when a further charge of attempting to forcibly overthrow the government was levelled at him.

Guruz, who served 438 days of his sentence before being released, told Index: “The two cases, though seeming to have fizzled out, are still continuing in courts. I use the qualifier ‘seeming to’ because you never know how things will turn out in the Turkish courts of today.”

“All of the prosecutors who prepared the indictments against me and all but one of the judges who presided over my trials in the past are either in jail or fired or have fled the country,” he added. “I understand what is going on today is a struggle between the legitimate government and the Gulenists who appear to have attempted a coup last summer, but I must add that the two sides were in cahoots in the past, especially in my two court cases.”

“Apparently, both sides hate my me for my staunchly secular and pro-Western stand.”

As Gulmen and Ozakca’s hunger strike continues, efforts to get the Turkish government to acknowledge them are growing more urgent. Index urges prominent public figures to follow the actions of David Harvey and speak out on Nuriye’s and Semih’s behalf in the form of a short video expressing solidarity. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/c9pyXZ8pTGc”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1496766579296-290161d0-415f-4″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Apr 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

What is usually the first pledge made by a politician who has won an election in his victory speech?

Erdogan’s was the death penalty.

Before the result of the 16 April referendum, which ended neck and neck, was even clear he came out onto the balcony and gave the “good news” to his supporters shouting “we want the death penalty!” that they would soon get their wish.

By abolishing the death penalty at the start of the 2000s, Turkey overcame an important obstacle in its negotiations with Europe. Now Erdogan is planning to bring back the death penalty, bombarding relations with Europe which are already at breaking point. And it was not just this. Two days after the referendum the government took the decision to extend the State of Emergency by three months. The extension of this emergency regime, which has been in force since 15 July 2016, was a concrete response to those expecting Erdogan to loosen the reins after the referendum. Sadly, Turkey now awaits not a time of relative peace, but a much more intense and chaotic period of repression.

There are a few different reasons for this.

The first is that it has become understood that Erdogan actually lost the referendum… Had the Supreme Electoral Board not taken the decision to count invalid votes as valid before the voting had even ended, Erdogan would not now be an executive president: he would be a leader who had lost a referendum. Since that day, hundreds of thousands of people have protested in the streets, shouting that their votes had been stolen. These protests have frightened the government, afraid they might turn into the Gezi uprisings of four years before. This is one reason for the increase in repression…

Another reason is that Erdogan has lost the big cities for the first time… The AKP, which has held onto key cities such as Istanbul and Ankara throughout its 15 years of power, has been beaten in these cities for the first time in this referendum. If we consider that Istanbul is the city in which Erdogan began his political career, it’s possible to say that his fall has also begun there. This is something that Erdogan will be losing sleep over…

Add to this disgruntlement an economy in the doldrums, especially with the wiping out of tourism revenues, and the withdrawal of the support from European capitals that had been given in pursuit of a refugee agreement, and you can understand why Erdogan is under so much pressure.

Now his only support comes from the Trump regime, which needs their help in Syria, from international capital which prefers authoritarian power to democratic chaos and from the social democratic opposition, still searching for a solution through a legal system that has long ago passed into Erdogan’s hands…

Can Erdogan balance out his shunning by Europe with the relationships he is striving to build with Trump and Putin?

By being part of the Syrian war, can he undo the tensions that are mounting at home?

Can he rein in the growing Kurdish problem by keeping jailed the co-presidents and around 10 MPs belonging to the HDP, the political representatives of the Kurds?

Can he hide the repression, lawlessness, and theft by jailing 150 journalists, silencing hundreds of media organs, throwing the foreign press out of the country and even punishing those who tweet?

I don’t think so.

All the data points to this last referendum being the beginning of the end for Erdogan. He will not go quietly, because he can guess what will happen to him if he loses power. But from here on in, he will pay a heavy price for every repressive act.

Just before the referendum, Theresa May visited Turkey and, turning a blind eye to the human rights violations, signed a contract for the construction of warplanes. Things in Ankara may have changed a great deal by the time those planes are ready.

Maybe in London too…

Yet those in Turkey fighting at the cost of their lives for democracy, a free media, and gender equality will never forget that the leader of a country accepted as “the cradle of these principles” did not even once mention them when she arrived in Ankara to trade arms.

Erdoğan için sonun başlangıcı

Seçim kazanmış bir siyasetçinin zafer konuşmasında ilk vaadi ne olabilir?

Erdoğan’ınki idam cezası oldu.

16 Nisan’da yapılan ve neredeyse başabaş sona eren referandumun kesin sonuçları açıklanmadan, sarayının balkonuna çıktı ve “İdam isteriz” diye bağıran taraftarlarına, istediklerine çok yakında kavuşacakları “müjdesini” verdi.

Türkiye, idam cezasını 2000’lerin başında kaldırarak, Avrupa ile müzakerelerin önündeki önemli bir engeli aşmıştı. Şimdi Erdoğan, idam cezasını yeniden getirerek Avrupa ile zaten kopma noktasındaki ilişkileri bombalamaya hazırlanıyor.

Sadece o da değil, referandumdan iki gün sonra Hükümet, Olağanüstü Hal’i üç ay daha uzatma kararı aldı. 15 Temmuz darbe girişiminden beri uygulanan sıkıyönetim rejiminin uzatılması, referandumdan sonra Erdoğan’ın ipleri gevşeteceğini bekleyenlere somut bir cevap oldu.

Ne yazık ki, Türkiye’yi huzur değil, çok daha ağır ve kaotik bir baskı dönemi bekliyor.

Bunun birkaç nedeni var:

Birincisi, referandumu Erdoğan’ın aslında kaybettiğinin anlaşılması… Henüz sandıklar kapanmadan, Yüksek Seçim Kurulu’nun aldığı bir kararla, geçersiz oylar geçerli sayılmasa, Erdoğan şu an Başkan değil, referandum kaybetmiş bir liderdi. O günden beri, yüzbinlerce insan caddelerde oylarının çalındığını haykırarak protesto gösterisi yapıyor. Bu protestoların, 4 yıl önceki Gezi ayaklanmasına dönüşmesi, iktidarı korkutuyor. Baskının artırılmasının bir nedeni bu…

Bir başka neden, Erdoğan’ın ilk kez büyük kentleri kaybetmiş olması… 15 yıllık iktidarı boyunca İstanbul, Ankara gibi kilit kentleri elinde tutan AKP, ilk kez bu referandumda bu şehirlerde yenildi. İstanbul’un, Erdoğan’ın siyasi kariyerine başladığı kent olduğu düşünüldüğünde, düşüşünün de oradan başladığını söylemek mümkün. Bu da, Erdoğan’ın uykularını kaçıran bir unsur…

Bu huzursuzluğa bir de özellikle turizm gelirlerinin sıfırlanmasıyla düşüşe geçen ekonomiyi ve Avrupa başkentlerinin mülteci anlaşması uğruna verdikleri desteği çekmesini ekleyin; Erdoğan’ın neden bu kadar sıkıştığını anlarsınız.

Şimdi tek dayanağı, Suriye’de kendisine ihtiyaç duyan Trump rejimi, demokratik bir kaos yerine otoriter bir istikrarı tercih eden uluslararası sermaye ve çareyi çoktan Erdoğan’ın eline geçmiş yargı sisteminde arayan sosyal demokrat muhalefet …

Erdoğan, Avrupa’dan dışlanışını, Trump ya da Putin’le kurmaya çabaladığı ilişkiyle dengeleyebilir mi?

Suriye savaşına dahil olarak, içerde yaşadığı gerilemeyi tersine çevirebilir mi?

Kürtlerin siyasi temsilcisi olan HDP’nin eşbaşkanlarını ve 10’u aşkın milletvekilini hapiste tutarak tırmanan Kürt sorununu dizginleyebilir mi?

150 gazeteciyi hapsedip, yüzlerce medya organını susturarak, yabancı basını ülkeden kovup tweet atanları bile cezalandırarak, yaşanan baskıları, hukuksuzlukları, hırsızlıkları saklayabilir mi?

Bence hayır.

Bütün veriler, son referandumun Erdoğan için sonun başlangıcı olduğunu ortaya koyuyor. Düşerse başına gelecekleri tahmin ettiği için kolay çekilmeyecektir. Ancak bundan sonra her yapacağı baskı için ağır bedel ödeyecektir.

Başbakan Theresa May’in tam referandum öncesi yaptığı Türkiye ziyaretinde, insan hakları ihlallerini görmezden gelerek yapımına imza attığı savaş uçakları hazır olduğunda, Ankara’da işler hayli değişmiş olabilir.

Belki Londra’da da…

Yine de demokrasi için, özgür medya için, laiklik için, kadın-erkek eşitliği için canı pahasına mücadele veren Türkiyeliler, “bu ilkelerin beşiği” kabul edilen ülkenin liderinin silah ticareti için geldiği Ankara’da, bu ilkeleri ağzına bile almamasını asla unutmayacaktır.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1493982838323-862a9fef-6b14-3″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

21 Apr 2017 | Event Reports, News, Turkey

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Alp Toker of the 2017 Freedom of Expression Digital Activism Award-winning Turkey Blocks and Index on Censorship head of advocacy, Melody Patry. (Photo: Centre for Turkey Studies)

The Centre for Turkey Studies (CEFTUS) and Index on Censorship held a public forum at the House of Commons on Thursday 20 April 2017 to discuss the impact of the recent Turkish referendum as part of the 2017 Freedom of Expression Awards.

The referendum held on 16 April 2017 saw President Recep Tayyip Erdogan secure 51.3% of the vote to obtain sweeping presidential powers.

Chaired by former PEN International director Sara Whyatt, the debate focused on Turkey’s domestic and foreign policies and what the outcome of the referendum now means for freedom of expression in the European nation. The panel included Guney Yildiz, special adviser to the Foreign Affairs Select Committee, Alp Toker, founder of internet shutdown monitoring organisation Turkey Blocks, winner of the 2017 Freedom of Expression Digital Activism Award, and Index on Censorship’s head of advocacy, Melody Patry.

In his presentation, Yildiz took a broad stance in his observations on the referendum outcome.

The special adviser opposed the view that Turkey’s referendum primarily concerned Erdogan and his drive for increased powers. He claimed that “the movement towards a presidential system was already underway even before the referendum”.

“Something even more important is going on in Turkey, it’s a massive restructuring of the state and it goes beyond Erdogan,” the select committee adviser said.

Yildiz also argued that it was wrong for Turkey to be described as a “polarised society”, or to deem President Erdogan a “polarising figure” following the referendum results. He described Turkey as a “multi-polar country” with a “fragmented opposition” who were already divided among themselves over a host of other issues, divisions which they were unlikely to overcome.

“The proposition that this referendum is the beginning of the end of President Erdogan, in my opinion, is mistaken,” Yildiz said.

Yildiz went on to discuss the impact of the referendum on the Kurdish population, foreign policy and the future of Turkey.

The special adviser concluded: “Winning the presidency is a huge step, but it doesn’t mean that Erdogan is in any lack of challenges. I would say that these challenges are coming mostly from regional tensions, the Turkish economy and other structural changes rather than the Turkish opposition.”

Index’s head of advocacy Melody Patry spoke on the implications of the Turkish referendum on freedom of expression.

Patry explained that before the coup attempt in July 2016, Turkey was “not quite what we’d call a safe haven for free speech”. However, the onset of the coup accelerated the pace and widened the scope of the crackdown on both media freedom and freedom of expression more generally, with the government resorting to methods of intimidation. “We are now talking about not just thousands, but tens of thousands of academics, journalists, students having lost their jobs or being fired or detained,” Patry expressed.

Index’s head of advocacy also highlighted that, since July of this year, 150 journalists have been jailed and 159 media outlets closed in Turkey. These are only the cases that have been recorded due to the difficulties surrounding the monitoring of attacks on the press. “Because it is difficult to monitor, it is also difficult to hold Turkish government to account.”

Before the coup attempt, many journalists were arrested for crimes relating to defamation and terrorism. “These kinds of charges are all the more concerning at a time when after the referendum, Erdogan is talking about reestablishing the death penalty,” said Patry. “We know that being associated with terror and terrorism could potentially put a target on the back or the forehead for the death penalty.”

In presenting his views on the referendum, Turkish-British technologist Alp Toker began by looking at the positives arising from the election. “A huge turnout means huge engagement; people are interested in voting, they are engaged with the political process,” he said.

In contrast to the stance adopted by Yildiz, Toker felt that Turkey had indeed become more polarised. However, the technologist made it clear that this was not a conclusion that should be reached through opinion, but through independent observation — something which Turkey currently lacked. “We’re missing out on something which you might call truth,” he said.

When turning to the work of his organisation Turkey Blocks, which was used to monitor the internet during the election weekend, Toker confirmed that no incidents of mass scale internet shutdowns were identified. This, however, did not equate to the “all clear” for media freedom and security in Turkey. “In fact, some could interpret it as the opposite,” the technologist said. “One of the opinions I heard is that they [Turkish government] don’t feel the need to control the internet because it has other means of controlling opinions.”

In drawing to a close, Toker argued that a better understanding of what kind of freedom was expected in Turkey needed to be established before progress could be made. The technologist said that this was “not a problem to be fixed from the outside” and that a “multi-pronged approach” would need to be adopted in order to solve it. “It’s not going to help if we continue this post-election polarisation,” he concluded. [/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=obmYZsDBu6s”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Akın Atalay (Cumhuriyet Foundation Executive President; imprisoned since Nov. 12, 2016): Facing 11 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust”

Akın Atalay (Cumhuriyet Foundation Executive President; imprisoned since Nov. 12, 2016): Facing 11 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust” Bülent Utku (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board Member, attorney representing Cumhuriyet; imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust”

Bülent Utku (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board Member, attorney representing Cumhuriyet; imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust” Murat Sabuncu (editor-in-chief, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” [Turkish Penal Code (TCK) Article 314/2]

Murat Sabuncu (editor-in-chief, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” [Turkish Penal Code (TCK) Article 314/2] Kadri Gürsel (publications advisor, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

Kadri Gürsel (publications advisor, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”  Güray Öz (board member, news ombudsman, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 8.5 to 22 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”

Güray Öz (board member, news ombudsman, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 8.5 to 22 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”  Önder Çelik (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and four counts of “abuse of power in office”

Önder Çelik (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and four counts of “abuse of power in office”  Turhan Günay (editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet’s book supplement, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 8.5 to 22 years for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”

Turhan Günay (editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet’s book supplement, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 8.5 to 22 years for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”

Hakan Karasinir (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Hakan Karasinir (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and two counts of “abuse of power in office” ![]() Mustafa Kemal Güngör (attorney, board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”; two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Mustafa Kemal Güngör (attorney, board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”; two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Orhan Erinç (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board President, columnist). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member” ; four counts of “abuse of power in office”

Orhan Erinç (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board President, columnist). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member” ; four counts of “abuse of power in office”  Aydın Engin (columnist, released under judicial control measures). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”

Aydın Engin (columnist, released under judicial control measures). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”  Hikmet Çetinkaya (columnist, board member, released under judicial control). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”; two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Hikmet Çetinkaya (columnist, board member, released under judicial control). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”; two counts of “abuse of power in office”  Ahmet Şık (Correspondent, imprisoned since Dec. 30, 2016). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

Ahmet Şık (Correspondent, imprisoned since Dec. 30, 2016). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”  İlhan Tanır (former Washington correspondent, resides abroad). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

İlhan Tanır (former Washington correspondent, resides abroad). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”  Bülent Yener (Finance Manager). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”

Bülent Yener (Finance Manager). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”