16 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Ukraine

(Photo: Anatolii Stepanov / Demotix)

The Ukrainian parliament has adopted a new repressive law that seriously restricts freedom of expression and assembly, in a move the country’s civil society calls “a constitutional coup d’état”.

Law No. 3879, which enters into force tomorrow, criminalises libel (with a maximum sentence of two years of limited freedom), introduces criminal liability for “distribution of extremist materials”, allows blocking of websites and creates a Russian-style “foreign agent” definition for NGOs that use foreign funding.

Criminal liability for defamation and dissemination of extremist materials includes content posted online. The National Commission of State Regulation of Communication and Informatisation has the right to restrict access to websites “that are considered by experts to contain information that breaks the law.” Internet service providers will be obliged to buy special equipment to allow security services to monitor the internet and to restrict the access “to websites of information agencies that have no state registration.”

The law also requires mobile operators to identify SIM-cards owners; to buy a mobile contract one will have to present a passport and sign a formal contract.

The freedom of peaceful assembly is also threatened. In particular, the law forbids taking part in protests while wearing a helmet or a mask. Participating in a motorcade of five or more cars will lead to a fine and confiscation of the cars.

As the opposition tried to block the adoption of the draft law, the pro-government majority voted for the new legislative act with a simple show of hands, and without any discussion. The urgency of the law was explained by “a significant aggravation of [the] political and social crisis” in Ukraine.

“The law has been adopted by breaking all procedure rules. In fact it is a constitutional coup d’état that restricts fundamental freedoms and rights in Ukraine,” Olexandra Matviychuk, the chairperson of the Centre for Civil Liberties, told Index.

The restrictions outlined by the new law are aimed at civil society activists involved in the peaceful protests that started in Ukraine in November 2013 after the government refused to sign an association agreement with the EU.

This article was posted on 16 Jan 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

6 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News

In France, Bob Dylan is being officially investigated for “incitement to hatred” against Croats for comparing their relationship to Serbs with that between Nazis and Jews in an interview.

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression.

Freedom of information

Freedom of information is an important aspect of the right to freedom of expression. Without the ability to access information held by states, individuals cannot make informed democratic choices. Many EU member states have failed to adequately protect freedom of information and the Commission has been criticised for its failure to adequately promote transparency and uphold its commitment to freedom of information.

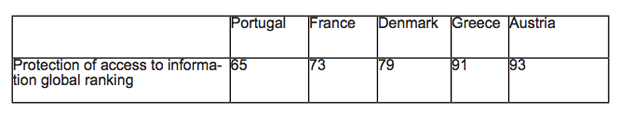

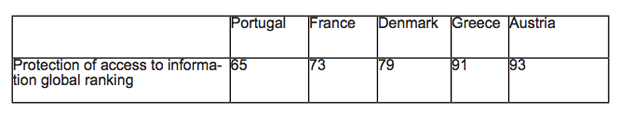

When it comes to assessing global protection for access to information, not one European Union member state ranks in the list of the top 10 countries, while increasingly influential democracies such as India do. Two member states, Cyprus and Spain, are still without any freedom of information laws. Of those that do, many are weak by international standards (see table below).

In many states, the law is not enforced properly. In Italy, public bodies fail to respond to 73% of requests.

The Council of Europe has also developed a Convention on Access to Official Documents, the first internationally binding legal instrument to recognise the right to access the official documents of public authorities. Only seven EU member states have signed up the convention.

Since the Lisbon Treaty came into force, both member states and EU institutions are both bound by freedom of information commitments. Article 42 (the right of access to documents) of the European Charter of Fundamental Rights now recognises the right to freedom of information for EU documents as a fundamental human right Further, specific rights falling within the scope of freedom of information are also enshrined in Article 41 of the Charter (the right to good administration).

As a result, the European Commission has embedded limited access to information in its internal protocols. Yet, while the European Parliament has reaffirmed its commitment to give EU citizens more access to official EU documents, it is still the case that not all EU institutions, offices, bodies and agencies are acting on their freedom of information commitments. The Danish government used their EU presidency in the first half of 2012 to attempt to forge an agreement between the European Commission, the Parliament and member states to open up public access to EU documents. This attempt failed after a hostile response from the Commission. Attempts by the Cypriot and Irish presidencies to unblock the matter in the Council also failed.

This lack of transparency can and has impacted on public’s knowledge of how decisions that affect human rights have been made. The European Ombudsman, P. Nikiforos Diamandouros, has criticised the European Commission for denying access to documents concerning its view of the United Kingdom’s decision to opt out from the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. In 2013, Sophie in’t Veld MEP was barred from obtaining diplomatic documents relating to the Commission’s position on the proposed Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA).

Hate speech

Across the European Union, hate speech laws, and in particular their interpretation, vary with regard to how they impact on the protection for freedom of expression. In some countries, notably Poland and France, hate speech laws do not allow enough protection for free expression. The Council of the European Union has taken action on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by promoting use of the criminal law within nation states in its 2008 Framework Decision. Yet, the Framework Decision failed to adequately protect freedom of expression in particular on controversial historical debate.

Throughout European history, hate speech has been highly problematic, from the experience and ramifications of the Holocaust through to the direct incitement of ethnic violence via the state run media during wars in the former Yugoslavia. However, it is vital that hate speech laws are proportionate in order to protect freedom of expression.

On the whole, the framework for the regulation of hate speech is left to the national laws of EU member states, although all member states must comply with Articles 14 and 17 of the ECHR.[1] A number of EU member states have hate speech laws that fail to protect freedom of expression –- in particular in Poland, Germany, France and Italy.

Article 256 and 257 of the Polish Criminal Code criminalise individuals who intentionally offend religious feelings. The law criminalises public expression that insults a person or a group on account of national, ethnic, racial, or religious affiliation or the lack of a religious affiliation. Article 54 of the Polish Constitution protects freedom of speech but Article 13 prohibits any programmes or activities that promote racial or national hatred. Television is restricted by the Broadcasting Act, which states that programmes or other broadcasts must “respect the religious beliefs of the public and respect especially the Christian system of values”. In 2010, two singers, Doda and Adam Darski, where charged with violating the criminal code for their public criticism of Christianity.[2] France prohibits hate speech and insult, which are deemed to be both “public and private”, through its penal code[3] and through its press laws[4]. This criminalises speech that may have caused no significant harm whatsoever to society, which is disproportionate. Singer Bob Dylan faces the possibility of prosecution for hate speech in France. The prosecutor’s office in Paris confirmed that Dylan has been placed under formal investigation by Paris’s Main Court for “public injury” and “incitement to hatred” after he compared the relationship between Croats and Serbs to that of Nazis and Jews.

The inclusion of incitement to hatred on the grounds of sexual orientation into hate speech laws is a fairly recent development. The United Kingdom’s hate speech laws contain specific provisions to protect freedom of expression[5] but these provisions are not absolute. In a landmark case in 2012, three men were convicted after distributing leaflets in Derby depicting a mannequin in a hangman’s noose and calling for the death sentence for homosexuality. The European Court of Human Rights ruled on this issue in its landmark judgment Vejdeland v. Sweden, which upheld the decision reached by the Swedish Supreme Court to convict four individuals for homophobic speech after they distributed homophobic leaflets in the lockers of pupils at a secondary school. The applicants claimed that the Swedish Supreme Court’s decision to convict them constituted an illegitimate interference with their freedom of expression. The ECtHR found no violation of Article 10, noting even if there was, the interference served a legitimate aim, namely “the protection of the reputation and rights of others”.

The widespread criminalisation of genocide denial is a particularly European legal provision. Ten EU member states criminalise either Holocaust denial, or the denial of crimes committed by the Nazi and/or Communist regimes. At EU level, Germany pushed for the criminalisation of Holocaust denial, culminating in its inclusion from the 2008 EU Framework Decision on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by means of criminal law. Full implementation of the Framework Decision was blocked by Britain, Sweden and Denmark, who were rightly concerned that the criminalisation of Holocaust denial would impede historical inquiry, artistic expression and public debate.

Beyond the 2008 EU Framework Decision, the EU has taken specific action to deal with hate speech in the Audiovisual Media Service Directive. Article 6 of the Directive states the authorities in each member state “must ensure by appropriate means that audiovisual media services provided by media service providers under their jurisdiction do not contain any incitement to hatred based on race, sex, religion or nationality”.

Hate speech legislation, particularly at European Union level, and the way this legislation is interpreted, must take into account freedom of expression in order to avoid disproportionate criminalisation of unpopular or offensive viewpoints or impede the study and debate of matters of historical importance.

[1] ‘Article 14 – discrimination’ contains a prohibition of discrimination; ‘Article 17 – abuse of rights’ outlines that the rights guaranteed by the Convention cannot be used to abolish or limit rights guaranteed by the Convention.

[2] The police charged vocalist and guitarist Adam Darski of Polish death metal band Behemoth with violating the Criminal Code for a performance in 2007 in Gdynia during which Darski allegedly called the Catholic Church “the most murderous cult on the planet” and tore up a copy of the Bible; singer Doda, whose real name is Dorota Rabczewska, was charged with violating the Criminal Code for saying in 2009 that the Bible was “unbelievable” and written by people “drunk on wine and smoking some kind of herbs”.

[3] Article R625-7

[4] Article 24, Law on Press Freedom of 29 July 1881

[5] The Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006 amended the Public Order Act 1986 by adding Part 3A[12] to criminalising attempting to “stir up religious hatred.” A further provision to protect freedom of expression (Section 29J) was added: “Nothing in this Part shall be read or given effect in a way which prohibits or restricts discussion, criticism or expressions of antipathy, dislike, ridicule, insult or abuse of particular religions or the beliefs or practices of their adherents, or of any other belief system or the beliefs or practices of its adherents, or proselytising or urging adherents of a different religion or belief system to cease practising their religion or belief system.”

19 Nov 2013 | Europe and Central Asia, Macedonia, News

The government of Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski has been heavily criticised for the state of media freedom in Macedonia (Image Toni Arsovski/Demotix)

Media freedom in Macedonia has been deteriorating for some time. The latest case is the arrest of Zoran Bozinovski, the owner of website critical of the government, Burevesnik on espionage charges. Below, Tamara Causidis, President of the Trade Union of Macedonian Journalists and Media Workers and Dragan Sekulovski, the Executive Director of Association of Journalists of Macedonia, chronicles the challenges facing the free press, in their submission to the upcoming International Federation of Journalists conference in Kiev.

—

The media business in Macedonia has been increasingly under attack over the past few years. The EU and the US State Department, as well as renowned non-governmental organisations like Freedom House and Reporters Without Borders, have all called attention to the decline of media freedom in the country. The challenges most often highlighted include imprisoned journalists, restrictive draft media laws, the government’s large advertising share, the lack of transparent ownership, and the polarisation of the media along lines of political and business affiliation. In light of this, freedom of the media and freedom of speech have been marginalised.

Macedonia has almost 200 media outlets, but unfortunately, that does not make the situation better. They all compete in a small, distorted market, covering just over 2 million citizens, where they cannot survive financially unless they align their interests with the governing parties and politically connected, large businesses. Apart from state media, the vast majority of the country’s press is in private hands. However, the government come out top among the 50 biggest advertisers in the country in 2012. The latest European Commission report raised this as a serious concern, and the DG Enlargement report of June says that at least 1% of the annual national budget (20 million Euros) is invested in media outlets through government campaigns and advertising. This highlights the authorities’ huge influence in the media sphere. Bearing in mind that there are no criteria for how to distribute these funds, “governmental friendly” media outlets are favoured over others. Professionals are fired and people with personal integrity are replaced by obedient mouthpieces, while a huge number of journalists are living in professional insecurity. Behind the veil of “economic reasons”, critical media is vanishing.

One of the most striking example of the situation Macedonian media finds itself in, took place on 24 December last year. Journalists reporting on the parliamentary session were expelled from Parliament by security forces without any reasonable explanation. The Association of Journalists of Macedonia (AJM) used all national legal measures to fight this, but so far no public official has been held liable for this breach of Article 16 of the constitution, which guarantees citizens the right to objective information. The next step would be submission of an appeal to the Court in Strasbourg.

In April the government announced a draft media law, now in its final stages within Parliament, which has the potential to further negatively affect media independence and freedom of expression. International and local organisations are concerned about the same issues regarding the bill – the intention to have one regulator for all types of media and the powerful role of this regulator, the issues concerning political independence, sustainable financing and high and disproportionate fines for the media, as well as the messy attempt to adopt definition of a journalist. The main Council of Europe, OSCE and AJM recommendations have not been accepted. In fact, the latest version of the law was updated with amendments which makes the text even more restrictive the before. For instance, it envisaged that authorities to decide which national association of journalists is legitimate, and will have the right to nominate a member to the council of the regulator and the public broadcaster.

In October 2013 Macedonia became the only country in south-east Europe with imprisoned journalists. Tomislav Kezarovski, from the daily Nova Makedonija, was sentenced to four and a half years in prison for in 2008 revealing the identity of a protected witness in a murder trial. The witness recently testified that he had given false evidence against the accused killers. The Trade Union of Macedonian Journalists and Media Workers (SSNM) and AJM organised two protests in front of court in Skopje, raising the issue in the international community, but despite this Kezarovski was sentenced on October 21.

It should also be noted that at the time, he was investigating the mysterious death of prominent journalist Nikola Mladenov, founder of the weekly Fokus and one of the biggest activists for press freedom in the country. AJM is taking daily initiatives to raise the visibility of this case, to try to convince authorities that this sends terrifying message to all journalists and endangers freedom of press even more.

Finally, many colleagues in the media cannot rely on any of the basic rights guaranteed by the Labour Law. They are working without contracts, insurance, paid vacation, overtime hours and sick leave, and minimum wage is not regulated. There aren’t any internal rules or statutes defining the rights and obligations of owners, editors and journalists, and there are instances of both direct and indirect bans for organising into workers unions. The journalists themselves are barely educated about what a union is and how they can organise through it. In the face of fierce criticism from AJM, the government has developed the Macedonian journalists association, designed not only to diminish critics and open confrontation but also to impose artificial support for the proposed media laws.

This text is drafted based on a draft report on the media situation in Macedonia by Tamara Causidis, President of the Trade Union of Macedonian Journalists and Media Workers and Dragan Sekulovski, Executive Director of Association of Journalists of Macedonia. It will be published at the upcoming conference organised by the International Federation of Journalists in Kiev.

This article was originally published on 19 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Oct 2013 | Campaigns, Europe and Central Asia, Events

Index on Censorship wants Europe’s leaders to place the issue of surveillance on the agenda for the European Council Summit. Our petition calling for this, backed by 39 organisations and thousands of individuals, was this week sent to Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaitė, who currently hold the Presidency of the Council of the EU, and Herman van Rompuy, President of the European Council.

Since the petition targets all 28 EU leaders, we wanted each of them to have their own copy. But as revelations continue to emerge about the scale to which electronic mass surveillance has been taking place, we didn’t think email would be the safest way to distribute it. Instead, we decided to send our intern Alice to deliver the petitions to embassies around London – the old fashioned way.

Marek Marczynski, Index’s Director of Campaigns and Policy, explains how mass surveillance infringes on your right to freedom of expression, and why we must oppose it.