22 Aug 2011 | Uncategorized

The German state of Schleswig-Holstein is pressuring websites to remove the Facebook “like” button, designed to link their content to the social networking site, by the end of September or face a fine of up to €50,000. Thilo Weichert, the spokesman for the regional office for data protection, has claimed that the button breaches German and EU privacy laws.

Weichert argues that the button permits Facebook to trace users’ internet activity and opinion of pages counts as illegally filing a collection of their browsing activity. “Facebook can trace every click on a website, how long I’m on it, what I’m interested in,” he told the Deutche Presse Agentur (German Press Agency). He also claimed that the US-based company would even collect data on those surfing who weren’t Facebook members, although how or why they would then use the “like” option is unclear.

Weichert has neglected to address precisely how the state is going to tackle this issue: will only sites based in Schleswig-Holstein be required to do this? An overall impression of Schleswig-Holstein as far from being an internet-hotspot (surely most sites have their servers or bases abroad?) doesn’t dispel the problem that policing this problem may require more of an intrusion into individual privacy than the “like” button supposedly presents in the first place. Schleswig-Holstein has further neglected to point out why the rest of Germany or the EU are yet to be up in arms about this; perhaps because most German or EU citizens realise that cure may be worse than the disease.

Facebook, for its part, defended itself by saying that the button is able to transport user data such as IP addresses, but that this data is kept for the 90 days that the industry permits, not permanently, and that all of its plug-ins comply with EU data protection law.

There is also the matter that the Facebook “like” button seems like a rather arbitrary target. This is a function where users are relatively well versed as to how it works, as the choice of when to it is made clear, rather than the altogether more invisible Google Analytics, which monitors users activity before and after clicking on websites and collects far more “intimate” data, such as the length of time spent on the page and the number of clicks. Granted, this doesn’t match up with a personal profile, making the data anonymous, so if privacy concerns are at the forefront then it would seem less pernicious at first glance. However, the data is given away entirely unawares, anxieties over which are really the crux of a privacy concern in the first place. If users volunteer their data, which they are already doing in droves to the anti-privacy behemoth that is Facebook, then surely concerns over privacy are null and void.

Privacy concerns are frequently the stick that the German government uses to beat the internet with, a cultural hang-up from the dark days of the GDR or even Nazi 20th century where extensive collection of individual data was the lynchpin of both oppressive regimes.

Ruth Michaelson is a freelance journalist living and working in Berlin

19 Aug 2011 | Uncategorized

Plenty are worried by the inconsistent sentences across England being handed down by a justice system tasked to crack down on participants in last week’s mass riots — years in jail for some, community service orders for others.

It raises fundamental questions about the independence of the judicary and its response to crimes one judge called “completely outside the usual context of criminality”. For most of the English court system, that seems particularly true of Facebook, Twitter and Blackberry “thought crimes”.

Thousands of connected citizens poured views, fears and news into social media during the night of August 9. A few exploited it to instigate — organise is barely the word — fast moving raiding parties to loot whole neighbourhoods amidst self-replicating chaos.

They wrongfooted a police force geared to manage public disorder usually scheduled around fixed objects — football games, nightclubs, the Houses of Parliament. The yobs moved faster on bikes than officers in body armour. Social media and encrypted messages by Blackberry greased their criminal intent.

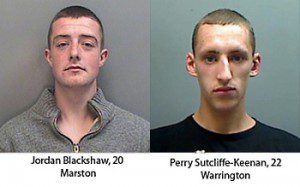

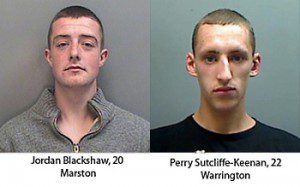

Then came the reckoning. Not Robespierre, but English magistrates and judges. Among the punished, Jordan Blackshaw and Perry Sutcliffe-Keenan, jailed for four years for using Facebook to fuel riots in Cheshire that never actually happened. In contrast, a 17-year-old who posted a Facebook message saying “come on rioters” was banned from social networking sites for 12 months and given a 120 hour community service order.

The disparity is attributed to the justice system running around sending, chasing and acting on false messages itself: “There has been a strong kneejerk reaction and lots of misinformation, including apparent orders, which turned out not to be true, that all parties should be given custodial sentences,” noted one defence lawyer.

This is the now notorious “directive” that sought to overturn sentencing guidelines that are standard in cases of major public disorder. Set after the 2001 Bradford riots by England’s Sentencing Council of experts and the Lord Chief Justice, it sets binding guidelines that allow judges to measure prospective punishment against actual harm done, culpability, remorse and early guilty pleas.

As the former Solicitor General for England and Wales Vera Baird writes, when the community is rightly angry it is the court’s duty to punish more severely, but it must still distinguish “the professional criminal from the easily led and every shade of culpability in between — and make the punishment fit the criminal”.

This is the nuance demanded by the sentencing guidelines. A similar nuance is required in applying principles of free expression, not an absolute human right, but one qualified by “certain restrictions provided by law“, including the protection of public order.

There is a straightforward difference between words and deeds. Measures in law that distinguish between expressions of hate and the incitement of an actual act of violence, that are provable in court and appropriately punishable.

But this week’s riot sentences come at the end of a decade of equal inconsistency in punishment of thought crimes — where no windows or bones are broken or property damaged, but public sensibilities have been battered.

Most of these cases are post-9/11, such as the jailing of six British demonstrators against the Danish Mohammed cartoons — for making an impractical threat to “Bomb Denmark” and “Kill British Soldiers in Iraq” — under England’s 1861 Offences against the Person Act. Or former airport worker and self-styled “lyrical terrorist” poet Samina Malik, convicted on terrorism charges later quashed on appeal.

Writing about Malik’s case, Index trustee Matthew Parris discussed her thought crime:

It’s all about that dividing line, so fragile and disputable yet so precious to those who believe in liberty, between what we may say, write or think, and what may be so directly linked to action as to deserve the name of action. One is the proper preserve of the individual; the other the rightful business of the police. Where we draw that line is critical and can only be a matter of opinion.

Sentencing is a matter of judicial opinion. Sentencing guidelines are there to guide it, says Baird, carefully guided analysis that produces sentences “compatible with legislation and appropriate to the five purposes of sentencing: punishment, protection of the public, deterrence, reform and rehabilitation and reparation to the public”.

Britain needs sentencing guidelines on punishments for these kinds of offences. The judge making the judgment in the case of Samina Malik, subsequently overturned on appeal, admitted that she was an “enigma” to him. How many judges would admit the same view of the world of social media communications?

Rohan Jayasekera is Associate Editor at Index on Censorship

19 Aug 2011 | Uncategorized

Plenty are worried by the inconsistent sentences across England being handed down by a justice system tasked to crack down on participants in last week’s mass riots — years in jail for some, community service orders for others.

It raises fundamental questions about the independence of the judicary and its response to crimes one judge called “completely outside the usual context of criminality”. For most of the English court system, that seems particularly true of Facebook, Twitter and Blackberry “thought crimes”.

Thousands of connected citizens poured views, fears and news into social media during the night of August 9. A few exploited it to instigate — organise is barely the word — fast moving raiding parties to loot whole neighbourhoods amidst self-replicating chaos.

They wrongfooted a police force geared to manage public disorder usually scheduled around fixed objects — football games, nightclubs, the Houses of Parliament. The yobs moved faster on bikes than officers in body armour. Social media and encrypted messages by Blackberry greased their criminal intent.

Then came the reckoning. Not Robespierre, but English magistrates and judges. Among the punished, Jordan Blackshaw and Perry Sutcliffe-Keenan, jailed for four years for using Facebook to fuel riots in Cheshire that never actually happened. In contrast, a 17-year-old who posted a Facebook message saying “come on rioters” was banned from social networking sites for 12 months and given a 120 hour community service order.

The disparity is attributed to the justice system running around sending, chasing and acting on false messages itself: “There has been a strong kneejerk reaction and lots of misinformation, including apparent orders, which turned out not to be true, that all parties should be given custodial sentences,” noted one defence lawyer.

This is the now notorious “directive” that sought to overturn sentencing guidelines that are standard in cases of major public disorder. Set after the 2001 Bradford riots by England’s Sentencing Council of experts and the Lord Chief Justice, it sets binding guidelines that allow judges to measure prospective punishment against actual harm done, culpability, remorse and early guilty pleas.

As the former Solicitor General for England and Wales Vera Baird writes, when the community is rightly angry it is the court’s duty to punish more severely, but it must still distinguish “the professional criminal from the easily led and every shade of culpability in between — and make the punishment fit the criminal”.

This is the nuance demanded by the sentencing guidelines. A similar nuance is required in applying principles of free expression, not an absolute human right, but one qualified by “certain restrictions provided by law“, including the protection of public order.

There is a straightforward difference between words and deeds. Measures in law that distinguish between expressions of hate and the incitement of an actual act of violence, that are provable in court and appropriately punishable.

But this week’s riot sentences come at the end of a decade of equal inconsistency in punishment of thought crimes — where no windows or bones are broken or property damaged, but public sensibilities have been battered.

Most of these cases are post-9/11, such as the jailing of six British demonstrators against the Danish Mohammed cartoons — for making an impractical threat to “Bomb Denmark” and “Kill British Soldiers in Iraq” — under England’s 1861 Offences against the Person Act. Or former airport worker and self-styled “lyrical terrorist” poet Samina Malik, convicted on terrorism charges later quashed on appeal.

Writing about Malik’s case, Index trustee Matthew Parris discussed her thought crime:

It’s all about that dividing line, so fragile and disputable yet so precious to those who believe in liberty, between what we may say, write or think, and what may be so directly linked to action as to deserve the name of action. One is the proper preserve of the individual; the other the rightful business of the police. Where we draw that line is critical and can only be a matter of opinion.

Sentencing is a matter of judicial opinion. Sentencing guidelines are there to guide it, says Baird, carefully guided analysis that produces sentences “compatible with legislation and appropriate to the five purposes of sentencing: punishment, protection of the public, deterrence, reform and rehabilitation and reparation to the public”.

Britain needs sentencing guidelines on punishments for these kinds of offences. The judge making the judgment in the case of Samina Malik, subsequently overturned on appeal, admitted that she was an “enigma” to him. How many judges would admit the same view of the world of social media communications?

Rohan Jayasekera is Associate Editor at Index on Censorship

17 Aug 2011 | Uncategorized

Two men jailed for four years over Facebook messages inciting disorder — their cases spark criticism of “disproportionate” sentences. Sara Yasin reports

(more…)