Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Hello, readers. This is Sarah Dawood here, the new editor of Index on Censorship. Every week, we bring the most pertinent global free speech stories to your inbox.

This week, headlines have been dominated by the ongoing devastation of the war in the Middle East, where the death toll is now more than 42,000 in Gaza, and more than 2,100 in Lebanon. Monday also marked a painful milestone for Israelis and Jewish people everywhere, as the first anniversary of Hamas’s attacks, which killed 1,200 people. You can read Jerusalem correspondent Ben Lynfield’s forensic analysis on the region’s risks to journalists and press freedom below.

Attention has also been on the destructive Hurricane Milton in Florida, which has killed at least 16 people. The climate event has resulted in human tragedy, physical damage and the distortion of truth, with false information and AI-generated images accumulating millions of views on social media, including a fabricated flooding of Disney World in Orlando. Such imagery has been seized upon by hostile states, far-right groups, and even US politicians to advance their own aims: Russian state-owned news agency RIA Novosti reposted the fake Disney World photos to its Telegram channel, whilst Republican members of Congress have proclaimed conspiracy theories of government-led “storm manufacturing”. This emphasises how crises can be manipulated and monopolised to stir up division.

But while disinformation can undermine democracy, so too can information blockades. This brings us to some important stories coming out of Latin America. In Brazil, the social media platform X is now back online after a shutdown in September. The platform was banned by a top judge during the country’s presidential election campaign, in an attempt to prevent the spread of misinformation. But as Mateus Netzel, the executive director of Brazil-based digital news platform Poder360 told Reuters, social media bans not only restrict public access to information, but can undermine journalists’ ability to gather and report on news. Elon Musk himself was using X to post about the development of the ban, but this was inaccessible to Brazilian journalists. “In theory, there are journalists and outlets who do not have access to that right now and this is a very important restriction because they need to report on this issue and they will have to rely on indirect sources,” said Netzel.

We also heard frightening news from Mexico, where a local politician was murdered and beheaded just days after being sworn in as city mayor of Chilpancingo. Whilst we don’t yet know the reason that Alejandro Arcos Catalán was killed, his murder is yet another example of journalists, politicians, and other public figures being routinely targeted by criminal gangs. Bar active war zones, Mexico has consistently been the most dangerous country in the world for journalists, topping Reporters Without Borders’ list in 2022.

Meanwhile, in El Salvador, climate activists are being silenced through false imprisonment. Five protesters, who fronted a 13-year grassroots campaign to ban metal mining due to its devastating environmental impacts are now facing life in prison for the alleged killing of an army informant in 1989. The charge has been condemned by the UN and international lawyers as baseless and politically motivated, and echoes heavy-handed prison sentences being handed to climate protesters globally, including in democratic countries. As Index’s Mackenzie Argent reported last month, human rights lawyers have called out the UK’s hypocrisy in claiming egalitarianism whilst disproportionately punishing environmental activists, pointing specifically to the sentencing of Just Stop Oil’s Roger Hallam to five years in prison in July. These two stories, although taking place 5,000 miles away from each other, underline how climate defenders are currently on the front line of attempts to be silenced.

Who could have predicted that Donald Trump would unite George Orwell and Taylor Swift in the form of an Index newsletter? But that’s the strange world in which we’re living.

This week I’ve been obsessively telling my Index colleagues about Laura Beers’ excellent book Orwell’s Ghosts, which is full of insights about today’s political climate through the lens of the Animal Farm author’s wisdom. One part that’s really stuck with me is the relationship between free speech and the truth, as Orwell saw it.

“Orwell could never endorse a world in which ‘alternative facts’ were given free rein,” Beers writes, reminding her readers about the famous Nineteen Eighty-Four line where Orwell describes freedom as the right to say that 2 + 2 = 4. As Beers points out, it is very much not the right to say that 2 + 2 = 5. Objective truth matters.

Anyone with even a passing interest in the US election will know that this week has been a goldmine for talking points on truth, lies and misinformation. It is the perfect moment to be reading this book.

When ABC News hosted a debate between Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump this week, it was also the first time they’d met in person. After shaking hands, the debate began with gusto, Harris quickly getting under Trump’s skin. What was particularly interesting about this debate though was the on-the-go fact-checking live on air. It’s something we’ve never seen to this degree, and the fact that ABC feel it is needed now is telling.

On the issue of abortion, Trump asserted — not for the first time — that babies in the USA are being executed after being born. Moderators took down the false claim: “There is no state in this country where it is legal to kill a baby after it’s born.”

Commentators on the right were quick to denounce this new era of fact-checking. It was unfairly skewed towards Trump and they were picking him apart more than Harris. There is of course a simple explanation for that, which is that he told more lies. According to CNN, Trump delivered more than 30 false claims while Harris gave one, although additional claims of hers were misleading or lacking in context.

The award for top untruth of the night goes perhaps to Trump’s claim that Haitian migrants in Springfield, Ohio, are eating people’s pet cats and dogs. The internet quickly got to work with memes of The Simpsons’ dog Santa’s Little Helper giving the side eye to cat Snowball II. But ABC moderators were speedier than the meme-makers and set the story straight live on air, confirming that there had been “no credible reports” of this alleged neighbourhood pet buffet.

Of course, the lie didn’t come out of thin air. As The Economist breaks down, the “allegation had been circulating in right-wing circles on social media, boosted by Elon Musk”. Amid anti-immigrant sentiment in some circles, a Facebook post “cited fourth-hand knowledge” about the cat-eating claim. A half-truth is still a lie. And when it comes to a Facebook post based on fourth-hand knowledge being pedalled by a would-be (and former) president, we’re not even close to the realms of a half-truth. Two plus two does not equal four. Two plus two equals Lassie for lunch.

Social media has played a starring role in the misinformation story. Perhaps now is a good time to move on to X owner and tech billionaire Elon Musk’s post directed at pop superstar Taylor Swift.

Following the TV debate, Swift endorsed Harris in an Instagram post to her 284 million followers (to Trump’s 26.5 million and Harris’s 16.9 million, just to demonstrate the sway she has), where she talked about her concern over AI-generated content claiming to show her endorsing Donald Trump. Beneath a picture of the Shake It Off singer holding her ragdoll cat Benjamin Button, she wrote: “The simplest way to combat misinformation is with the truth,” and signed off “Taylor Swift, Childless Cat Lady,” riffing off the sexist trope used by Republican vice presidential nominee JD Vance towards Harris and others.

While not distracted by SpaceX (one of his other companies), which yesterday launched the first ever privately-funded spacewalk, Musk found the time to post: “Fine Taylor … you win … I will give you a child and guard your cats with my life.” If we know anything about Swift it’s that Musk is about to become the villain in an upcoming hit single.

Trump also reacted to Swift endorsing Harris. He said the popstar would “probably pay a price for it in the marketplace”.

Swift might say: “Haters gonna hate”. But when powerful billionaires and presidential candidates are deriding cultural figures for having a political voice, and objective truth becomes optional in a democracy, there is a problem. As this and other elections continue to unfold, it’s everyone’s responsibility to make sure that two plus two continue to equal four.

When Turkey’s Kahramanmaraş province was hit by two powerful earthquakes on 6 February 2023, the government responded by attacking the country’s already beleaguered press and journalists. It is time now to take stock, lay bare abuses and ask the right questions.

Over 55,000 people died in the earthquakes in Syria and Turkey and thousands are still missing. In Turkey alone, there was a devastating effect on at least 10 provinces, wiping several cities off the map.

The harrowing aftermath of the earthquake was compounded by the government’s inadequacy in providing disaster relief. Beyond that came a series of measures to stop the media from reporting on the earthquake, ranging from detentions and intimidation to physical attacks.

In the time between the earthquakes hitting on 6 February and the first week of March, 10 journalists were taken into custody, with two of them arrested for their reports from the disaster ground. In addition to that, 26 journalists were targets of physical attacks or attempted attacks in the earthquake region, initiated by security forces and unidentified groups. A state agency gave three independent news stations astronomical fines, and journalists working in pro-government media have targeted at least three journalists for their work in the disaster region.

On 9 February, the day after the government declared a state of emergency in the affected regions, it blocked Twitter for up to 12 hours. This move didn’t only hinder the coordination of relief efforts, but also led to hundreds, maybe even thousands of lives being lost, as many earthquake victims were tweeting their status and asking for help from under the rubble in those most crucial hours.

Even for a government known for its repressive policies, why did shutting down social media and stopping the press take precedence over rescue efforts?

In Turkey, where the vast majority of media is in government hands and internet access restrictions are common, the earthquake laid bare the disastrous consequences of two decades of the Justice and Development Party (AKP).

Following the earthquakes, thousands of buildings collapsed, with yet thousands more severely damaged — believed by many construction experts to be a result of a series of amnesties which legalised unregistered developments, and the support for government-friendly construction companies.

The media exposed the links between the government and construction companies, which could easily obtain licenses for unfit buildings. This strictly contradicts the government’s narrative of the earthquake being the “disaster of the century”.

News reports on buildings — including that of the Kahramanmaraş Chamber of Civil Engineers, which survived the two quakes without so much as the glass of a window shattering — stood testimony to the fact that although the earthquakes were natural, the disaster was man-made.

Covering up these incidents by stopping journalism took precedence over saving lives.

The first earthquake-related detention occurred as early as 7 February, when Evrensel Daily’s Adana correspondent Volkan Pekal was taken into custody by police officers while filming at Adana City Hospital on charges of recording “without permission”.

By the third day after the earthquake, four journalists had been detained while filming or interviewing in the affected cities. Many journalists now face investigations under Turkey’s newest “fake news” law which makes “spreading misleading news publicly” a crime punishable by up to three years in prison.

On 27 February, local journalists and brothers Ali İmat and İbrahim İmat from the earthquake-stricken town of Osmaniye were arrested on the same charge. They exposed how hundreds of tents in Osmaniye were kept in storage houses, instead of being distributed to survivors.

There were also threats. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan told journalists the government was monitoring those who were critical of Turkey’s handling of the disaster. Turkey’s state broadcast monitoring agency, the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK), issued Halk TV, Tele 1 TV and Fox TV with five programme suspensions and administrative fines for their news reports on the disaster.

More than one month after the earthquake, many cities still don’t have running water; debris and rubble haven’t been cleared up in many places. Survivors still don’t have access to tents, let alone housing. With general elections due in two months, instead of addressing the needs of survivors and putting in place procedures to ensure that the next earthquake will not result in a similar outcome, the government of Turkey still chooses to demonise and punish independent journalism.

FEATURING

Author

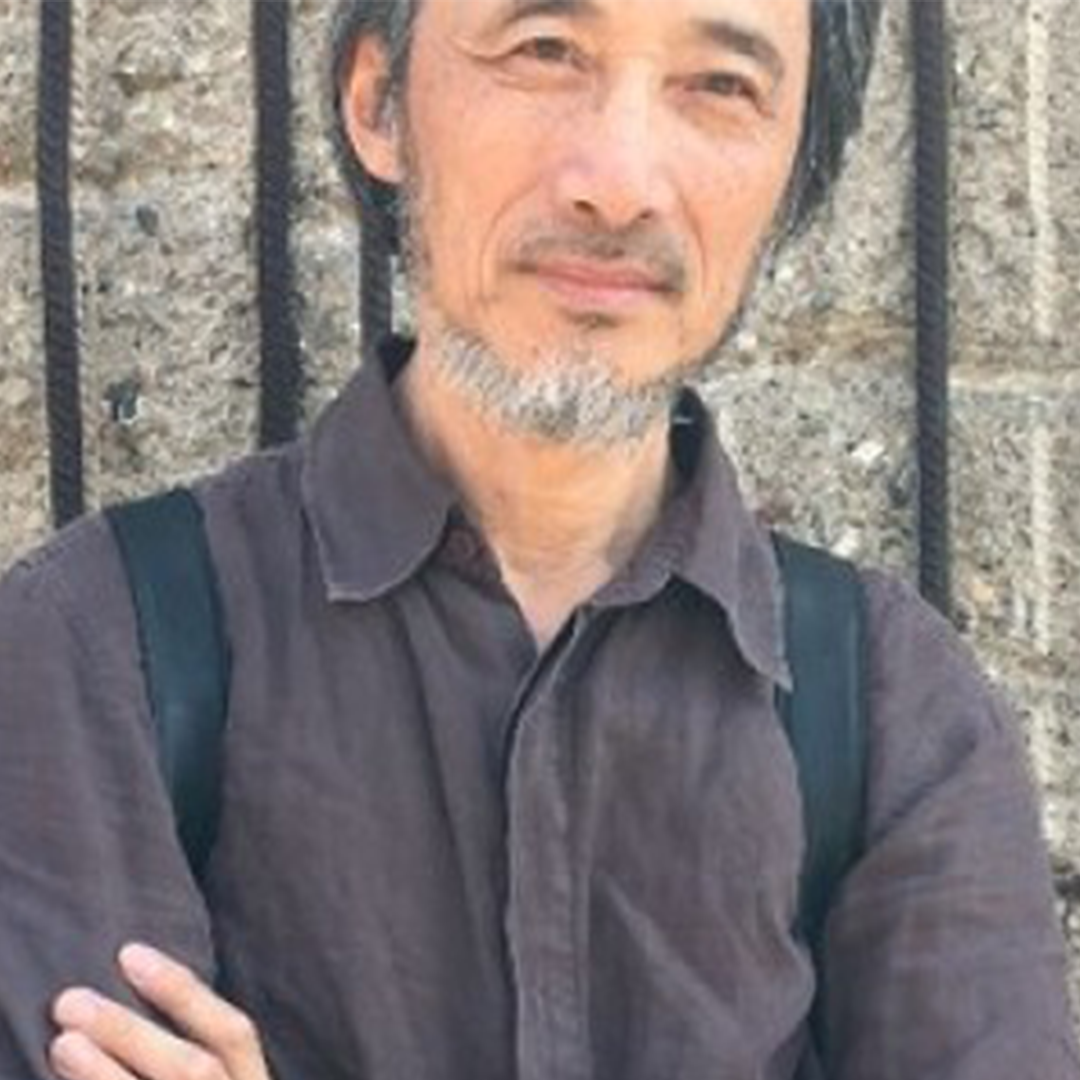

Ma Jian is an award-winning Chinese writer. His latest novel is China Dream. His work is banned in China

Singer

Journalist

Sarah Sands is Chair of the Gender Equality Advisory Council for G7 and a board member of Index on Censorship. Sands was the former editor of BBC’s Today programme