13 Jun 2017 | Digital Freedom, News, Pakistan

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Journalist Azaz Syed said that reporters are being told to self-censor. (Photo: YouTube)

Nine Pakistani citizens have filed a constitutional petition in Pakistan’s Sindh High Court in response to recent harassment and arrests of journalists and activists. The petition was filed Monday 5 June, naming the Federation of Pakistan and Federal Investigation Agency as respondents.

The petitioners, who are journalists and activists, include Farieha Aziz. Aziz is the director of Bolo Bhi, a Pakistani nonprofit that promotes digital freedom and gender rights through advocacy and research, though the group was not part of the petition. Bolo Bhi won Index on Censorship’s 2016 Freedom of Expression Campaigning Award.

“We’ve approached court because as citizens we believe the government has acted unlawfully and its actions are creating an environment of fear, in turn causing a chilling effect on speech,” Aziz told Index. “As citizens and professionals we believe we must collect to take such initiatives in the interest of democracy and to ensure that rule of law is upheld.”

The petitioners are responding to government actions that they claim have a “chilling effect on freedom of speech”. Pakistan’s government has been using cyber crime laws to crackdown on activists who criticise the military. On 10 May, the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority texted citizens a message cautioning against blasphemous online content and suggesting that they report any such content. Pakistan’s cyber crime laws allow the government to censor material online. This followed an order in March from the Islamabad High Court to remove blasphemous material from all websites, even if that meant blocking those websites.

Pakistan has become an increasingly hostile environment for journalists and critics of government actions. In January, five prominent online critics of Pakistan’s military went missing within a few days of each other, and their websites were immediately blocked. Last week, Geo news journalist Azaz Syed escaped an attempted kidnapping in Islamabad, and the perpetrators have not yet been identified. Another journalist from Geo TV, Hamid Mir, was seriously wounded in a gun attack last year.

This is not the first time Syed has been confronted with threats and attacks because of his work. In 2010 he received threatening phone calls and his home was attacked, and although he was able to name his assailants the police have yet to lodge an official complaint. This time, Syed has avoided naming his attackers as he fears for the security of his family.

Syed describes the changing environment for journalists as moving away from physical attacks. News organisations are encouraging journalists not to anger those in power, even pushing them to avoid posting on social media. According to Syed, only those who do not listen and continue to post are at risk of physical attack. “This is happening because the culprits involved in attacking the journalists never face the long arm of law,” Syed told Index. “Everything ultimately goes to the imbalance of civil-military relations in the country.”

On 14 May, the minister of the interior ordered the FIA to take action against individuals suspected of carrying out anti-military campaigns online. The FIA has continued to detain people suspected of participating in this type of campaign.

Activist Adnan Afzal Qureshi was arrested by FIA on 31 May for “anti-military tweets” and “abusive language against military personnel and political leaders,” according to the FIA. He was charged under sections of the law relating to “offence against the dignity of a natural person” and “cyberstalking”.

The FIA has sent notices to other activists instructing them to report to the counter-terrorism wing of the police station. The notices do not include any suspected offences, or the type of information FIA is seeking.

The petitioners called the government and the FIA’s actions violations of due process. In their statement, they condemn the government’s actions as “coercive acts to intimidate, harass and threaten not just targeted individuals but citizens at large,” which they accuse of attempting to inhibit the public’s exercise of rights.

The respondents were instructed to file a response by 15 June, which was later adjourned to 25 June.

In another development, an anti-terrorism court in Pakistan sentenced Taimoor Raza to death on 11 June for committing blasphemy in a Facebook post. His offence consisted of disparaging the Prophet Muhammad and other religious figures.The exact contents of the post have not been released, but Raza was arrested following a debate about Islam on Facebook with a counter-terrorism agent last year. He was charged with the maximum sentence under laws punishing derogatory remarks about religious figures, and a law concerning derogatory remarks about Prophet Muhammad. This is the first death sentence for a social media post in Pakistan.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1497944568388-6fea101c-dfb2-3″ taxonomies=”23″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” content_placement=”middle”][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”91122″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/05/stand-up-for-satire/”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

5 Oct 2016 | Asia and Pacific, Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2016, News, Pakistan

Farieha Aziz, director of 2016 Freedom of Expression Campaigning Award winner Bolo Bhi (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Pakistan’s Prevention of Electronic Crimes Bill 2015, better known as the cyber crimes bill, has severe implications for freedom of expression and the right to access information in the country.

After a lengthy process, the bill was signed into law on 22 August 2016. Bolo Bhi, the Pakistani non-profit promoting digital freedoms and winner of the 2016 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression award for campaigning, has been fighting the bill through all it’s stages and will continue to do so even now it has been approved.

“We are looking at what will be the right approach and the current debate is whether we jump to court and challenge it on constitutional grounds or wait for there to be an executive review and then build a case around it,” Farieha Aziz, director of Bolo Bhi, told Index on Censorship.

Bolo Bhi has reached out to other organisations and individuals, including the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan and several lawyers, during its campaign against the bill, and if legal action is to be taken it will be a class action involving all of all of these parties.

“We’ve gotten some of the best constitutional minds in the country to start looking at the law and where we go from here,” Aziz said.

Such action would be costly and, as pro bono doesn’t always guarantee success, the group have begun reaching out to people who may be able to provide support.

At this early stage amendments to the bill won’t be possible. “So we want to build pressure through public dialogue in terms of what’s wrong with the bill and what needs to be fixed,” Aziz said. “We will also raise awareness of how this law can be used against various communities.”

Pakistan has a large youth population – they very people having most conversations online – and they need to know how the bill will impact them, Aziz explained, so Bolo Bhi has been doing a lot of work with students. “We want to see the youth take ownership of this issue and see that discussion around such laws should not be relegated to the legal fraternity or the legislature.”

In terms of building pressure, the movement needs that student community voice. “It’s something we can’t leave untapped,” said Aziz.

Fighting the bill took up a lot of Bolo Bhi’s time over the past year and the organisation doesn’t currently have a staff beyond Aziz and fellow director Sana Saleem, nor an office in which to work from.

But fortunes may be changing. As Index spoke with Aziz, a possible fund to cover operational costs and salaries for a year was on the cards for Bolo Bhi. The organisation has always been small and even with this funding it would remain so, allowing it to stay focused on certain issues.

“And maybe in the next month or two we will even have an operational office again,” Aziz added.

With this in mind, Aziz is hopeful that Bolo Bhi will be send more time on its gender work. “We’re members of the Women’s Action Forum and with the recent passing of the anti-domestic violence bill there’s been a lot of discussion on the provincial protection of women, so that’s something we are focusing on,” she said.

On a case-by-case basis, a lot of victims and survivors of abuse get in touch with the network. “Just yesterday we spoke to a young girl who was forcibly married at 15, is now divorced with a young child and is being harassed by her own family,” Aziz explained. “We’re now trying to get protection and see what legal proceedings are necessary.”

This is just some of the work that goes on on the side and is what Aziz hopes she can do more of in future.

As always, the main challenge is funding.

“While it’s important for us to keep on top of the issues, at the same time we’re trying to get enough support to keep us afloat.”

Also read:

Smockey: “We would like to trust the justice of our country”

Zaina Erhaim: Balancing work and family in times of war

Artist Murad Subay worries about the future for Yemen’s children

GreatFire: Tear down China’s Great Firewall

Nominations are now open for 2017 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards. You can make yours here.

11 Aug 2016 | Asia and Pacific, mobile, News, Pakistan

Farieha Aziz, director of 2016 Freedom of Expression Campaigning Award winner Bolo Bhi (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Pakistan’s National Assembly passed a controversial Prevention of Electronics Crimes Bill on Thursday 11 August. The bill will permit the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority to manage, remove or block content on the internet.

Many critics say the bill is too overarching and punishments too severe. It also leaves children as young as 10 liable for punishment.

Farieha Aziz, director of Index-award winning Bolo Bhi, the Pakistani non-profit fighting for internet freedom, has been campaigning against the bill for over a year. Last month, Aziz told Index: “It’s part of a regressive trend we are seeing the world over: there is shrinking space for openness, a lot of privacy intrusion and limits to free speech.”

Last week, Aziz was selected by the Young Parliamentarians Forum – a bi-partisan forum with representation from all political parties – as one of the 10 Youth Champions of Pakistan. Yesterday – the day before the bill passed – each recipient was given three minutes to speak to the speaker of the National Assembly, Sardar Ayaz Sadiq, and other parliamentarians.

Yesterday, Aziz used her three minutes to criticise the bill based on the below letter to members of YPF. She emailed a similar letter to Ayaz Sadiq, who left before she gave her speech.

Dear Members of YPF,

Thank you for nominating and selecting me as one of the 10 youth champions of Pakistan.

I stand before you today apparently in recognition of efforts made to secure the rights of Internet users. I regret though that this is no moment for personal recognition or glory, not when the future of the youth of Pakistan stands threatened. What is that threat? The Prevention of Electronic Crimes Bill, which is on today’s orders of the day of the National Assembly, set to receive the approval of parliament and become law.

For over a year, not just I, but many citizens and professionals fought long and hard to fix this bill. We engaged with the government and opposition. Provided input to make the law better. We never said there shouldn’t be a law but that the law needed to respect fundamental rights and due process. While we found many allies among you – parliamentarians without whose efforts it would have been an even more difficult struggle – there were many part of the same system who labelled us as agents and propagandists.

On one occasion, the doors of parliament house were shut upon us. Stack loads of written input was disregarded and we were told we were just noise-makers who’d given nothing at all.

How I wish the certificate awarded today was actually a significantly amended version of the bill. A bill that did not trample on the rights of citizens. A bill that factored in the input we’d provided. I have come here today not for the certificate, but to ask you, if you will commit to the youth of this country beyond certificates?

The youth of this country is losing hope. I come to ask you if you will do all that is in your power to do, to restore it. If you want to give the youth of this country hope, then do not dismiss them. Do not stick labels. Do not isolate them. They don’t need certificates to give them hope. They need to see that things will be done differently – that their input will be considered and that you will constructively engage with them. That you will enter questions, and motions and resolutions on vital issues that concern citizens. That you will wage a struggle within your parties to make them see differently on issues. And that you will use your vote when it counts, and block legislation that seeks to take away our constitutionally guaranteed freedoms and rights.

If the bill is passed today, in its current form, the message that will go out to the youth of Pakistan is that there is no room or tolerance for thinking minds and dissenting voices. Should the youth inquire and raise questions, a harsh fine and long jail term awaits them. Is this the future you want to give the youth of Pakistan? If not, then when you go to the National Assembly today at 3pm, stop the bill from becoming law. Allow time to fix it.

Show the youth of this country that not only will you recognize efforts outside parliament; but that you will also honour these efforts by casting your vote to protect their rights inside parliament too. If you do this, that would be true recognition.

Thank you.

Farieha Aziz

Concerned citizen, digital rights activist and journalist

25 Jul 2016 | Africa, Asia and Pacific, Burkina Faso, Middle East and North Africa, News, Pakistan, Syria, Yemen

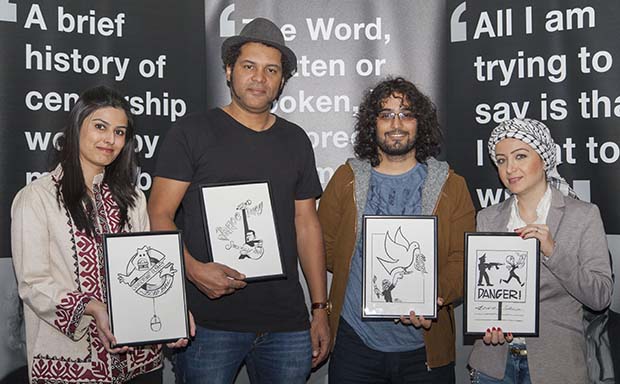

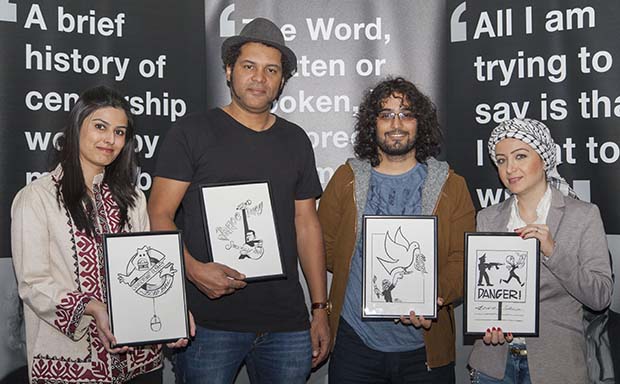

Winners of the 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards: from left, Farieha Aziz of Bolo Bhi (campaigning), Serge Bambara — aka “Smockey” (Music in Exile), Murad Subay (arts), Zaina Erhaim (journalism). GreatFire (digital activism), not pictured, is an anonymous collective. Photo: Sean Gallagher for Index on Censorship

In the short three months since the Index on Censorship Awards, the 2016 fellows have been busy doing important work in their respective fields to further their cause and for stronger freedom of expression around the world.

GreatFire / Digital activism

GreatFire, the anonymous group of individuals who work towards circumventing China’s Great Firewall, has just launched a groundbreaking new site to test virtual private networks within the country.

“Stable circumvention is a difficult thing to find in China so this new site a way for people to see what’s working and what’s not working,” said co-founder Charlie Smith.

But why are VPNs needed in China in the first place? “The list is very long: the firewall harms innovation while scholars in China have criticised the government for their internet controls, saying it’s harming their scholarly work, which is absolutely true,” said Smith. “Foreign companies are also complaining that internet censorship is hurting their day-to-day business, which means less investment in China, which means less jobs for Chinese people.”

Even recent Chinese history is skewed by the firewall. The anniversary of Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 last month went mostly unnoticed. “There was nothing to be seen about it on the internet in China,” Smith said. “This is a major event in Chinese history that’s basically been erased.”

Going forward, Smith is optimistic for growth within GreatFire, and has hopes the new VPN service will reach 100 million Chinese people. “However, we always feel that foreign businesses and governments could do more,” he said. “We don’t see this as a long game or diplomacy; we want change now and so I feel positive about what we are doing but we have less optimism when it comes to efforts outside of our organisation.”

Winning the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for Digital Activism has certainly helped morale. “With the way we operate in anonymity, sometimes we feel a little lonely, so it’s nice to know that there are people out there paying attention,” Smith said.

Murad Subay / Arts

During his time in London for the Index awards, Yemeni artist Murad Subay painted a mural in Hoxton, which was the first time he had worked outside of his home country. “It was a great opportunity to tell people what’s going on in Yemen, because the world isn’t paying attention,” he explained to Index.

Since going home, Subay has continued to work with Ruins, his campaign with other artists to paint the walls of Yemen. “We launched in 2011, and have continued to paint ever since.”

Last month, artists from Ruins, including Subay, painted a number of murals in front of the Central Bank of Yemen to represent the country’s economic collapse.

In his acceptance speech at the Index Awards, Subay dedicated his award to the “unknown” people of Yemen, “who struggle to survive”. There has been little change in the situation since in the subsequent months as Yemenis continue to suffer war, oppression, destruction, thirst and — with increasing food prices — hunger.

“The war will continue for a long time and I believe it may even be a decade for the turmoil in Yemen to subside,” Subay says. “Yemen has always been poor, but the situation has gotten significantly worse in the last few years.”

Subay considers himself to be one of the lucky ones as he has access to water and electricity. “But there are many millions of people without these things and they need humanitarian assistance,” he says. “They are sick of what is going on in Yemen, but I do have hope — you have to have hope here.”

The Index award has also helped Subay maintain this hope. As has the inclusion of his work in university courses around the world, from John Hopkins University in Baltimore, USA, and King Juan Carlos University in Madrid, Spain.

Subay’s wife has this month travelled to America to study at Stanford University. He hopes to join her and study fine art. “Since 2001 I have not had any education, and this is not enough,” he explains. “I have ideas in my head that I can’t put into practice because i don’t have the knowledge but a course would help with this.”

Zaina Erhaim / Journalism

Syrian journalist and documentary filmmaker Zaina Erhaim has been based in Turkey since leaving London after the Index Awards in April as travelling back to Syria isn’t currently possible. “We don’t have permission to cross back and forth from the Turkish authorities,” she told Index. “The border is completely closed.”

Erhaim is with her daughter in Turkey, while her husband Mahmoud remains in Aleppo.

“The situation in Aleppo is very bad,” she said. “A recent Channel 4 report by a friend of mine shows that the bombing has intensified, and the number of killings is in the tens per day, which hasn’t been the case for some weeks; it’s terrible.”

The main hospital in Aleppo was bombed twice in June. “Sadly this is becoming such a common thing that we don’t talk about it anymore,” Erhaim added.

She has largely given up on following coverage of the war in Syria through US or UK-based media outlets. “It is such a wasted effort and it’s so disappointing,” she explained. “I follow a couple of journalists based in the region who are actually trying to report human-side stories, but since I was in London for the awards, I haven’t followed the mainstream western media.”

Erhaim has put her own documentary making on hold for now while she launches a new project with the Institute for War and Peace Reporting this month to teach activists filmmaking skills. “We are going to be helping five citizen journalists to do their own short films, which we will then help them publicise,” she said.

Documentary filmmaking is something she would like to return to in future, “but at the moment it is not feasible with the situation in Syria and the projects we are now working on”.

Bolo Bhi / Campaigning

The last time Index spoke to Farieha Aziz, director of Bolo Bhi, the Pakistani non-profit, all-female NGO fighting for internet access, digital security and privacy, the country’s lower legislative chamber had just passed the cyber crimes bill.

The danger of the bill is that it would permit the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority to manage, remove or block content on the internet. “It’s part of a regressive trend we are seeing the world over: there is shrinking space for openness, a lot of privacy intrusion and limits to free speech,” Aziz told Index.

Thankfully, when the bill went to the Pakistani senate — which is the upper house — it was rejected as it stood. “Before this, we had approached senators to again get an affirmation as they’d given earlier saying that they were not going to pass it in its current form,” Aziz added.

Bolo Bhi’s advice to Pakistani politicians largely pointed back to analysis the group had published online, which went through various sections of the bill and highlighting what was problematic and what needed to be done.

This further encouraged those senators who were against the bill to get the word out to their parties to attend the session to ensure it didn’t pass. “It’s a good thing to see they’ve felt a sense of urgency, which we’ve desperately needed,” Aziz said.

“The strength of the campaign throughout has actually been that we’ve been able to band together, whether as civil society organisations, human rights organisations, industry organisations, but also those in the legislature,” Aziz added. “We’ve been together at different forums, we’ve been constantly engaging, sharing ideas and essentially that’s how we want policy making in general, not just on one bill, to take place.”

The campaign to defeat the bill goes on. A recent public petition (18 July) set up by Bolo Bhi to the senate’s Standing Committee on IT and Telecom requested the body to “hold more consultations until all sections of the bill have been thoroughly discussed and reviewed, and also hold a public hearing where technical and legal experts, as well as other concerned citizens, can present their point of view, so that the final version of the bill is one that is effective in curbing crime and also protects existing rights as guaranteed under the Constitution of Pakistan”.

A vote on an amended version of the bill is due to take place this week in the senate.

Smockey / Music in Exile Fellow

Burkinabe rapper and activist Smockey became the inaugural Music in Exile Fellow at the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards, and last month his campaigning group Le Balai Citoyen (The Citizen’s Broom) won an Amnesty International Ambassador of Conscience Award.

“This was was given to us for our efforts in the promotion of human rights and democracy in our country,” said Smockey. The award was also given to Y en a marre (Senegal) and Et Lucha (Democratic Republic of the Congo).

“We are trying to create a kind of synergy between all social-movements in Africa because we are living in the same continent and so anything that affects the others will affect us also,” Smockey added.

Le Balai Citoyen has recently been working on programmes for young people and women. “We will also meet the new mayor of the capital to understand all the problems of urbanism,” Smockey added.

While his activism has been getting international recognition, he remains focused on making music with upcoming concerts in Belgium, Switzerland and Germany, and he is currently writing the music for an upcoming album. A major setback has seen Smockey’s acclaimed Studio Abazon destroyed by a fire early in the morning of 19 July. According to press reports the studio is a complete loss. The cause is under investigation.

Despite this, Smockey is still planning to organise a new music festival in Burkina Faso. “We want to create a festival of free expression in arts,” Smockey said. “And we are confident that it will change a lot of things here.”

He is thankful for the exposure the Index Awards have given him over the last number of months. “It was a great honour to receive this award, especially because it came from an English country,” he said. “My people are proud of this award.”