Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

In early April 2016, major Hungarian news website vs.hu began publishing less than normal. On 25 April a dozen journalists, including editor-in-chief Olivér Lebhardt, resigned. While the newsroom is still functioning, its future is yet to be decided by its owners, according to daily newspaper Népszabadság.

The mass resignation was prompted by revelations that the site, owned by New Wave Media (NWM), had received funding from foundations established by the Hungarian National Bank, the country’s central bank. The financing totaled more than 500 million HUF ($1.8 million).

NWM is owned by Czech company Bawaco Invest, which, Hungarian news site 444.hu reported, can be linked to Tamás Szemerey, a cousin of the central bank’s governor, György Matolcsy. The company issued a statement denying Szemerey’s ownership, according to the Financial Times.

The educational foundations were established in 2014 by Matolcsy, a politician allied to Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán. The foundations were endowed with over 314 billion forints ($1.1 billion) of central bank funding that was then invested in government bonds, Reuters reported.

The finances of these foundations were kept secret, but after a ruling from the country’s constitutional court in March, their contracts were published on 22 April 2016. Since then, the press has delighted in revelations of the foundations’ profligacy, The Economist wrote. The bank’s foundations spent money on real estate and artworks, as well as funding web projects covering social and economic issues.

“I was informed by the editor-in-chief a day before [the NWM disclosures], on Wednesday 21 April 2016,” Attila Bátorfy, one of the journalists who resigned told Index on Censorship. “That day there was a meeting, where István Száraz, the CEO of the publishing company deferred to answer the journalist’s questions. Then on Friday, he was talking about only a couple hundred of million HUF, but we knew there would be a huge scandal.”

On the evening of 23 April the first articles about the foundations’ spending were published. The next day vs.hu journalists issued a joint statement saying that while some of them knew that part of their editorial projects were sponsored by the bank’s foundations, they had no knowledge of the extent of the financing, Bátorfy recalled.

“We are also surprised and shocked by the data published by the foundations,” the journalists wrote. The editorial team said that there was no interference with the content of the articles — even in projects that were sponsored.

“On that Saturday evening, we held an emergency meeting in my apartment. About 15 colleagues were present, and we talked about the minimal requirements we, as journalists, expect from our publisher, to consider continuing our work at vs.hu. We had no opportunity to present these demands, because in his opening speech the CEO made it clear that the situation is beyond hope,” Bátorfy recalled.

“Journalists started to hand in their resignations. Those working for the politics, economy, culture and multimedia sections said the situation made their work impossible, they lost credibility, and there is no reason to continue,” he told Index.

Bátorfy, who had worked for vs.hu for three months, said that he had accepted the role after he was told that the site was financed by private and state advertising and money from the owner.

In the wake of the revelations, the Editor-in-Chief’s Forum issued a statement asking parliament to pass a law that would require the transparent disclosure of ownership and state funding of media outlets. “This would be beneficial to the market transparency, and would decrease the defenselessness of the media workers,” the group said.

Hungary’s ruling conservative Fidesz party has been making changes to the country’s media market since it came to power in 2010. Most recently the government cut funding to culture magazines. In 2015 Hungarian public media laid off scores of journalists as its funding was cut, according to reports on MMF. In the case of Hungarian private TV station RTL Klub, an ongoing conflict led to a ban of its news reporters and the dismissal of the television network’s CEO. Observers like 2014 Index award-winning Tamás Bodoky have noted that government advertising contracts have been used as a “powerful censorship instrument”.

Access to information was restricted through a series of amendments in the freedom of information law in July 2015, but the free movement of journalists in the parliament building was also strictly regulated. As a consequence, journalists trying to ask questions about the National Bank scandal were banned from the Parliament.

On Tuesday 26 April 2016, a number of media outlets received notes from House Speaker László Kövér, in which the Fidesz politician informed them that their journalists were barred from entering the building for “filming without a permit” and “consciously breaking the rules”. The ban came a day after journalists attempted to question Fidesz politicians, including Orbán and Kövér. While journalists and camera crews followed MPs, they entered into a secure area that was out of bounds to members of the press.

The editor-in-chief of Népszabadság newspaper (nol.hu), András Murányi, wrote a response to the letter: “I can assure you that Népszabadság had no intention of breaking the rules. The goal of journalists working at Népszabadság was to ask those who are elected and are paid representatives of the people questions regarding public affairs, and to publish their answers. As for answers – as we could see this time again – we seldom get any, as we are more and more prevented to act as free press in Parliament (…) lately we can only do our job in a constricted area,” Murányi said.

Mapping Media Freedom

|

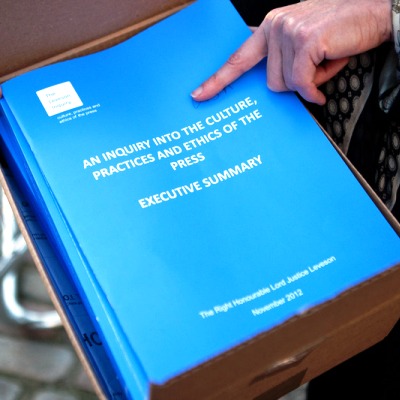

In an editorial published this morning, the Financial Times announced its support for the Royal Charter on press regulation put together by the newspaper industry.

The article said that while the FT agreed with the need for a “robust and independent regulation”, a new regulator should be “proportionate and sustainable.”

The article continued:

“Well-meaning reforms should not open the door to state interference in Britain’s free press.”

Acknowledging that the press had reluctantly accepted that there would be a royal charter for regulation of the press, the Financial Times argued:

[C]ertain points are non-negotiable. If press freedoms are to be preserved, the regime must be genuinely voluntary. It should also balance public protection with freedom of expression. A financially weak press should not be loaded with onerous obligations that deter it from pursuing contentious issues, where reporting serves the public interest and holds the powerful to account.

The industry’s plans to create the Independent Press Standards Organisation were revealed earlier this month. Index on Censorship greeted the proposal as “a starting point for proper discussion on the future“.

Hacked Off, which supports the government’s regulation proposal, reacted angrily to the Financial Times’ suggestion that that document had been “assembled over pizza in the early hours of the morning this spring”.

Director Brian Cathcart denied his group had been present at late-night negotiations, pointing out: “No pizza was served, or at least we saw none.”

The Financial Times, the Guardian, and the Independent this week shifted their position towards a compromise on press regulation. Index criticises the change of stance, which risks threatening press freedom

The censorship and control-freakery imposed by Locog makes a mockery of the idea that the London Olympics are open and inclusive, says Kirsty Hughes

The censorship and control-freakery imposed by Locog makes a mockery of the idea that the London Olympics are open and inclusive, says Kirsty Hughes

(more…)