8 Aug 2013 | France, News and features, Politics and Society

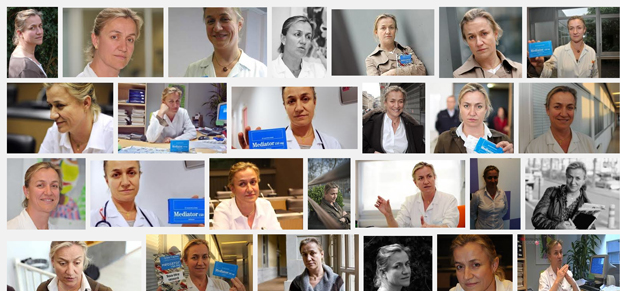

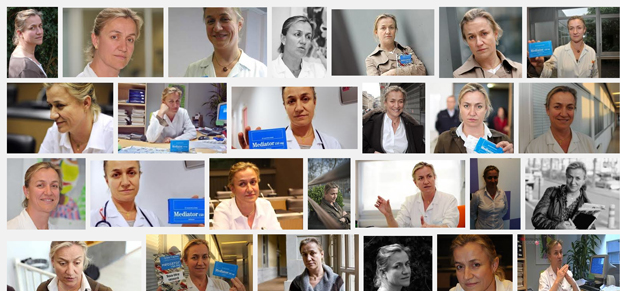

Irène Frachon is a French pneumologist who discovered that an antidiabetic drug frequently prescribed for weight loss called Mediator was causing severe heart damage.

The French term “lanceur d’alerte” [literally: “alarm raiser”], which translates as “whistleblower”, was coined by two French sociologists in the 90’s and popularised by scientific André Cicolella, a whistleblower who was fired in 1994 from l’Institut national de recherche et de sécurité [the National institute for research and security] for having blown the whistle on the dangers of glycol ethers.

While the history of whistleblowing in the United States is closely associated with the case of Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times in 1971, exposing US government lies and helping to end the Vietnam war, whistleblowing in France was first associated with cases of scientists who raised the alarm over a health or an environmental risk.

In England, the awareness that whistleblowers needed protection grew in the early 1990s, after a series of accidents (among which the shipwreck of the MS Herald of Free Enterprise ferry, in 1987, which caused 193 deaths) when it appeared that the tragedies could have been prevented if employees had been able to voice their concerns without fear of losing their job. The Public Interest Disclosure Act, passed in 1998, is one of the most complete legal frameworks protecting whistleblowers. It still is a reference.

France had no shortage of national health scandals in the 1990s, from the case of HIV-contaminated blood to the case of growth hormone. But no legislation followed. For a long time, whistleblowers were at the center of a confusion: their action was seen as reminiscent of the institutionalised denunciations that took place under the Vichy regime when France was under Nazi occupation. In fact, no later than this year, some conservative MPs managed to defeat an amendment on whistleblowers’ protection by raising the spectre of Vichy.

For Marie Meyer, Expert of Ethical Alerts at Transparency International, an anti-corruption NGO, this confusion makes little sense: “Whistleblowing is heroic, snitching cowardly”, she says.

“In France, the turning point was definitely the Mediator case, and Irène Frachon,” Meyer adds, referring to the case of a French pneumologist who discovered that an antidiabetic drug frequently prescribed for weight loss called Mediator was causing severe heart damage. In 2010, Frachon published a book – Mediator, 150mg, Combien de morts ? [“Mediator, 150mg, How Many Deaths?”] – where she recounted her long fight for the drug to be banned. Servier, the pharmaceutical company which produced the drug, managed to censor the title of the book and get it removed from the shelves two days after publication, before the judgement was overturned. Frachon has been essential in uncovering a scandal which is believed to have caused between 500 and 2000 deaths. With scientist André Cicolella, she has become one of the better-known French whistleblowers.

“What is striking is that people knew, whether in the case of PIP breast implants or of Mediator”, says Meyer. “You had doctors who knew, employees who remained silent, because they were scared of losing their job.”

This year, the efforts of various NGOs led by ex whistleblowers were finally met with results. Last January, France adopted a law (first proposed to the Senate by the Green Party) protecting whistleblowers for matters pertaining to health and environmental issues. The Cahuzac scandal, which fully broke in February and March, prompting the minister of budget to resign over Mediapart’s allegations that he had a secret offshore account, was instrumental in raising awareness and created the political will to protect whistleblowers.

For Meyer, France’s failure to protect whistleblowers employed in the public service has had direct consequences on the level of corruption in the country.

“Even if a public servant came to know that something was wrong with the financial accounts of a Minister, be it Cahuzac or someone else, how could he have had the courage to say it, and risk for his career and his life to be broken?” she says.

In June, as France discovered Edward Snowden’s revelations in the press over mass surveillance programs used by the National Security Agency, it started rediscovering its own whistleblowers: André Cicolella, Irène Frachon or Philippe Pichon, who was dismissed as a police commander in 2011 after his denunciations on the way police files were updated. Banker Pierre Condamin-Gerbier, a key witness in the Cahuzac case, was recently added to the list, when he was imprisoned in Switzerland on the 5th of July, two days after having been heard by the French Parliamentary Commission on the tax evasion case.

Three new laws protecting whistleblowers’ rights should be passed in the autumn. France will still be missing an independent body carrying out investigations into claims brought up by whistleblowerss, and an organisation to support them, like British charity Public Concern at Work does in the UK.

So far, French law doesn’t plan any particular protection to individuals who blow the whistle in the press, failing to recognise that, for a whistleblower, communicating with the press can be the best way to make a concern public – guaranteeing that the message won’t be forgotten, while possibly seeking to limit the reprisal against the messenger.

6 Aug 2013 | Digital Freedom, France, Germany, Guest Post, News and features, Politics and Society, Russia, United Kingdom, United States

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Around the world, there is confusion and alarm over the impact of the U.S. National Security Agency’s (NSA) surveillance program on human rights. In the U.S., the debate is focusing on the gross violations of privacy rights of Americans. Barely a word is being spoken about the human rights of people outside the country whose personal communications are being targeted, and whose communications content is collected, stored, analyzed and used with little legal protection.

A growing group of international civil society groups and individuals wants that to change and is coming together to present the newly empowered U.S. Privacy and Civil Liberties Board (PCLOB) with a joint letter, asking the Board to make “recommendations and findings designed to protect the human rights not only of U.S. persons, but also of non-U.S. persons.” Before PCLOB’s mid-September deadline for public comments, I encourage global civil society to add their name to this powerful statement.

As the letter makes clear, there is great concern from the global community that the recently revealed surveillance program conducted under Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) poses a severe threat to human rights. It rightly notes that the surveillance “ strikes at the heart of global digital communications and severely threatens human rights in the digital age.” “The use of unnecessary, disproportionate, and unaccountable extra-territorial surveillance not only violates rights to privacy and human dignity, but also threatens the fundamental rights to freedom of thought, opinion and expression, and association that are at the center of any democratic practice. Such surveillance must be scrutinized through ample, deep, and transparent debate. Interference with the human rights of citizens by any government, their own or foreign, is unacceptable.”

Why then is all the attention in the U.S. focused on just the rights of Americans? The U.S. draws its obligations to protect rights in conducting surveillance from the U.S. Constitution, specifically the Fourth Amendment, which protects “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures.” The “people” generally means all people located within the United States regardless of citizenship, and then only when they have a “ reasonable expectation of privacy.”

Except in the most extraordinary circumstances, and for U.S. citizens and lawful residents when they are travelling abroad, people outside the U.S. have no privacy protections under the Fourth Amendment. This is a feature in the U.S. Constitution and it animates every part of U.S. surveillance law and practice. That is why Section 702 of FISA requires targeting and minimization guidelines that are aimed (albeit inadequately) at ensuring that the communications being targeted are those of people reasonably believed to be outside the U.S. It’s also why they provide some level of protection for ordinary Americans whose communications are ensnared in foreign intelligence activities and take no notice of the rights of ordinary people all over the world whose personal communications now reside in NSA databases.

It may be hard to fathom now, but Congress created the FISA Court to rein in surveillance after revelations about illegal political spying on Americans surfaced in the 1970’s. The Court had a narrow charge: to ensure that electronic surveillance conducted in the United States for intelligence purposes is conducted pursuant to a warrant. The warrant protection did not apply to surveillance conducted outside the U.S., so it did not protect the rights of foreigners outside the U.S. However, in those days, communications surveillance within the U.S. was a limited and highly targeted activity aimed at hostile foreign powers and their agents. The phone conversations of ordinary people were of no interest. International phone calls between a person in the U.S. and person abroad were quite expensive and relatively rare.

Today, the assumptions that informed the enactment of FISA have been worn thin by a radical shift in threats – from states to diffuse non-state actors – and an even more radical shift in technology. The advent of the internet, the data storage revolution and big data analytics, fueled by fears about terrorism, have, in the post-PATRIOT Act world, fueled a growing government appetite for data. Today, the NSA isn’t just trying to listen in on the embassy abroad of a Cold War rival; instead, it doesn’t know whom to listen in on because it does not know who might pose a threat. In the process, individualized targeting based on specific indicia of threat has given way to bulk programmatic targeting of foreign communications without any consideration of human rights of people beyond our borders.

This position is simply untenable in today’s much smaller world, where the Cold War line between “us” and “them” has blurred.

When FISA was enacted, there was no global internet and the cost of international calls was prohibitive. Large parts of the world were unreachable for political or technical reasons. Now, we are a nation of more immigrants, global businesses and frequent travelers. We live online and carry our cell phones everywhere. The cost of an international call has plummeted by more than 90% and the number of U.S. billed international calls and the use of VOIP has skyrocketed. Skype calls worldwide alone grew 44% to 167 billion minutes in 2012.

Everyday, Americans are calling, emailing, texting and “friending” family, friends, colleagues and customers around the world, engaging in so-called “foreign communications.” For those on the other side of our emails and calls, there is no protection for free expression or privacy rights. In fact, their communications may be collected, examined and used by the government for any legal purpose.

The U.S. is certainly not alone in the breadth of its surveillance activities. Britain’s spy agency monitors the cables that carry the world’s phone calls and internet traffic in close cooperation with the NSA. Indeed, according to leaked documents, Britain’s GCHQ collects more metadata than the NSA with fewer limitations. Germany’s foreign intelligence agency, the BND, is monitoring communications at a Frankfurt communications hub that handles international traffic to, from and through Germany, and the BND is seeking to significantly extend its capabilities. Le Monde reports that France runs a vast electronic spying operation using NSA-style methods, but with even fewer legal controls. And Russia’s notorious SORM system is reportedly even more advanced than the American system.

The U.S. is also not alone in focusing most of the protections of its surveillance laws internally. Such focus is also a feature of the surveillance laws and practices in democratic countries around the world, most of which take a highly territorial view of their human rights obligations and are unlikely to willingly give them extraterritorial application.

There is an urgent conversation to be had in the U.S and beyond about the implications of cross-border surveillance. Given the globalization of information society services, we now must assume that the data pertaining to the citizens of one country will flow through the infrastructure of another and be subject to collection and use for national security purposes. Surveillance standards must be strengthened everywhere to ensure that robust judicial oversight and that principles of specificity, necessity, proportionality, data minimization, use limitation and redress for misuse are the norm. In a globally networked world, legal standards must also recognize the human rights implications of cross-border surveillance and set out a way forward to protect the rights of people beyond state borders. There is ambiguity about whether our largely territorial human rights paradigm is adequate to meet the challenge.

That is why the call to PCLOB to speak to the rights of non-Americans is so important. PCLOB has a simple mission: to make sure privacy and civil liberties are at the table as new security measures to protect the nation are considered. It has boldly taken on the NSA surveillance program as its first task, but it is too soon to know whether it has the muscle or the will power to push meaningful reforms. It has an opportunity to show global leadership by heeding the call to make concrete recommendations about the rights of non-U.S. persons that can frame the global discussion about surveillance and human rights going forward. Add your name to the letter and tell PCLOB to seize the opportunity.

30 Jul 2013 | France, News and features, Politics and Society

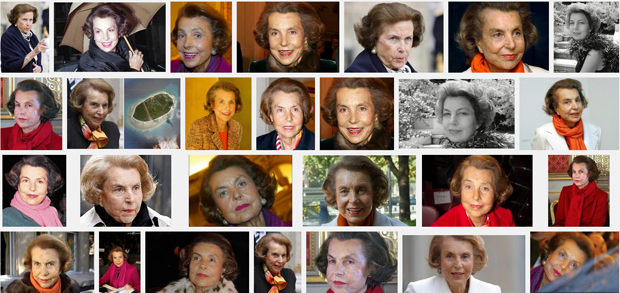

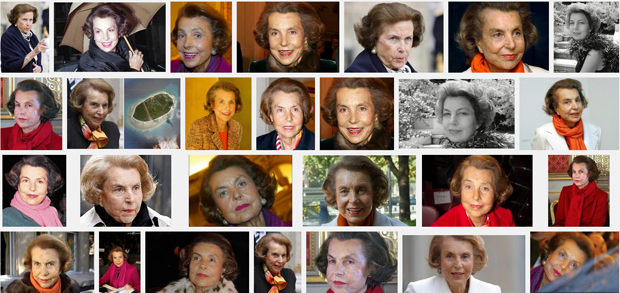

In a controversial ruling, a French court has ordered Mediapart to withdraw Bettencourt “butler tapes” from its website.

Since Tuesday 3 November 2015, the fourth part of the Bettencourt case is being judged in a Bordeaux court. This time the accused is Pascal Bonnefoy, former butler of Liliane Bettencourt. Bonnefoy is accused of privacy violations in conjunction with media outlets Le Point and Mediapart, which reproduced excerpts of recordings Bonnefoy had made. The tapes allowed the French justice system to condemn several people for abuse of a vulnerable person — the L’Oréal heiress — and spawned investigations into alleged corruption.

Following a court decision that became effective on Monday 22 July 2013, independent French news website Mediapart has had to withdraw the infamous Bettencourt “butler tapes” from its website, as well as 72 articles including quotes from the recordings, prompting a campaign of solidarity in the French and international media.

In the balance between freedom to inform and right to privacy, the court ruled that it was more important to protect the right to privacy. Reporters Without Borders published the censored content on Wefightcensorship.org, a website that has until now published content from countries more commonly associated with abuses of press freedom, such as Turkmenistan, China and Belarus.

Between 2009 and 2010, Pascal Bonnefoy, the butler of L’Oréal heiress, 87 year-old Liliane Bettencourt, secretly recorded conversations between his boss and Patrice de Maistre, her wealth manager, as well as other advisers. As Bonnefoy explained in a recent interview with French Vanity Fair, he did this because he thought Bettencourt was being manipulated by a close circle of advisers and friends. Apalled by the conversations he had intercepted, he gave the recordings to Bettencourt’s daughter who gave them to representatives of the justice system.

A 21 hour-long copy of the tape also came in possession of Mediapart and Le Point magazine. Journalists at the two publications edited down the content to one hour, getting rid of references to Liliane Bettencourt’s private life. What they kept was damning: the excerpts published in June 2010, contained, among other things, evidence of tax evasion and influence peddling, they raised suspicions of illegal political funding and interference in justice proceedings by a French presidential adviser.

The butler tapes have been at the centre of a lengthy investigation, as the Bettencourt case gradually unfolded, turning into the Bettencourt-Woerth case (when it appeared that Eric Woerth, successively budget and labour minister during Sarkozy’s presidential term, was involved) and the Sarkozy case, when France’s ex-president was placed under investigation over allegations that he had accepted illegal donations. The recordings were recognised as evidence by the criminal chamber of the appeal court in January 2012 and will be at the centre of a trial in Bordeaux, which date is still to be announced.

Meanwhile, following a complaint by Bettencourt’s legal guardian and by her former wealth manager, the Versailles appeal court ruled on 4 July that Mediapart and Le Point had to take down the recordings and all direct quotes from it or face significant financial penalties (10,000 euros per day per infraction). They will also have to pay 20,000 euros of damages to Bettencourt if her representatives claim the fee.

“What’s the balance between the freedom to inform and the right to privacy? This is the question raised by this ruling”, says Antoine Héry, head of the World Press Freedom Index at Reporters Without Borders. For him, the excerpts of the recordings used by Mediapart and Le Point are of public interest. “Erasing this content means erasing a part of this country’s collective memory”, he says. “Mediapart has written a lot about the case, which marks an important moment of French Fifth Republic’s history, and possibly one of the greatest scandal it has known,” he adds. The ruling might have a chilling effect – and make it more difficult for journalists to break stories in the future, for fear of costly court proceedings and fees. It will also make it complicated for Mediapart to write about the upcoming Bordeaux court case, as its journalists won’t be able to quote from the recordings, which constitute a very central piece of evidence.

“This decision”, says Edwy Plenel, a former Le Monde editor, who co-founded Mediapart in 2008 with other former print journalists, “is incredibly backwards, and recalls the very reactionary decisions taken by the judiciary system during the Second Empire, which showed an increasing tension towards the growing modernity of the publishing world and journalism.” For Plenel, the verdict can only be read as a reaction to changes prompted by the Internet – which allows a free circulation of information. It is part of a greater debate which has been taking place around the Snowden and Wikileaks case, and the Condamin-Gerbier case in Switzerland, where national security, banking secrecy and protection of privacy are opposed to the right to inform. Mediapart will appeal to the decision in France and take the case to the European Court of Human Rights if needs be.

The solidarity campaign which immediately followed the Versailles court decision has shown that such a verdict was absurd in the era of internet. After three years, the Bettencourt file has entered the public domain and has been copied everywhere: it’s easy to find on BitTorrent or Reflets.info. Following the verdict, several publications immediately offered to host the content that Mediapart was obliged to censor as a sign of protest. Among them, Belgian national newspaper Le Soir, French publications such as rue89 website, Les Inrockuptibles magazine or Arrêt sur Images website. Media organisations, NGOs and unions launched an appeal entitled “We have the right to know” supported by 53,000 signatures, which said: “When it comes to public affairs, openness should be the rule and secrecy the exception.”

Following the Streisand effect, the Versailles verdict seems to have backfired. Never have so many people listened to the Bettencourt tapes, nor read about the story, nor be interested in Mediapart, an investigative journalism website which has proven its ability to set the news agenda in France, and created a new business model as French printed press sunk deeper into crisis – Mediapart charges readers for access and doesn’t carry any advertisement.

Le Monde, France’s most well-known newspaper, abstained from the solidarity campaign, as well as conservative newspaper Le Figaro, a decision seen by many as disappointing, given that Le Monde was associated with Wikileaks and Offshore Leaks earlier this year.

“For me”, says Plenel, “this can be explained by a certain illiberal tradition within the French press, the fact that in this country journalism is often too close to political power, and also by a certain fear of the changes that Internet is causing in the media – embodied by Mediapart.” This distrust of new media associated with the Internet could explain the smear campaign endured by Mediapart by a good part of the traditional and conservative press from December last year, when the website broke the Cahuzac scandal (also prompted by a tape) which caused France’s budget minister to resign in April, finally admitting that he had a secret offshore account. France’s traditional written press seems to have become extremely cautious, and unable to break scandals, a task which was filled for a long time by the satirical weekly publication Le Canard Enchaîné, and now is also filled by Mediapart.

How does France rank on the Press Freedom Index?

“It’s only 37”, says Héry. A mediocre rank explained by the mediocrity of the law framing the protection of sources for journalists, and by reforms passed during Sarkozy’ presidency which streightened governmental control over France Télévisions, the French public national television broadcaster – allowing France’s president to name its CEO. Hollande’s government is expected to work on these issues – and new laws on the protection of sources for journalists, the status of whistleblower, and the nomination of the head of France Television should be passed. On Friday, the appeal launched in solidarity with Mediapart was handed to Aurélie Fillippetti, minister of culture and communication of the Hollande government, as well as the whole Bettencourt file.

Interestingly, the Versailles verdict took place on the same day France refused to grant asylum to Edward Snowden – a strong reminder that France could do a lot better to protect the right to inform and to be informed.

1 Jul 2013 | Campaigns, Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia

The revelations that the United States allegedly spied on European Union diplomats marks a low in what should be a special relationship of trust between major democracies. The EU needs to remind the US that surveillance is unacceptable in the digital age.

The row was prompted by revelations published by German magazine Der Spiegel on its website this past Saturday. Relying on documents allegedly leaked by the former NSA-contractor Edward Snowden, the magazine said the NSA had surveilled EU, French, German and Italian diplomatic offices in Washington and at the UN.

Instead of reminding US authorities of the EU belief in an open and free internet, Catherine Ashton, the high representative of the EU for foreign affairs and security policy, focused on the specific press reports, calling them a “matter for concern”. The European Union needs to reiterate its well-established position that “global connectivity should not be accompanied by censorship or mass surveillance.”

But French president Francois Hollande demanded the US stop its activities “immediately.” Later, the BBC reported that Hollande threatened to derail US-EU trade pact negotiations over the bugging scandal.

Germany’s government summoned the US ambassador to explain his country’s actions. Steffen Seibert, spokeperson for Chancellor Merkel, said that Germany wants “trust restored. We will clearly say that bugging friends is unacceptable.”

French foreign minister Laurent Fabius demanded an explanation “as soon as possible” after labelling the alleged spying unacceptable.

Martin Schulz, president of the EU Parliament warned that the allegations, if true, would have a “severe impact on the relations between the EU and the US. He demanded a fuller account of the Der Spiegel reports.

Thomas Drake, a former NSA employee turned whistleblower, who was prosecuted under the US espionage act tweeted today that the alleged spying had “little to do with classic eavesdropping. Instead, it’s closer to a complete structural acquisition of data”.

Index CEO Kirsty Hughes said:

“As disagreement grows between the EU and the US over surveillance, Index on Censorship calls for the EU to take a lead in condemning mass surveillance – which the EU’s cyberstrategy already warns against. We are also calling on the US government to acknowledge that the mass surveillance of citizens’ private communications is unacceptable and a threat to both privacy and freedom of expression.”