13 Apr 2016 | Academic Freedom, mobile

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A drawing by French cartoonist t0ad

Freedom of expression is a fundamental human right. It reinforces all other human rights, allowing society to develop and progress. The ability to express our opinion and speak freely is essential to bring about change in society.

Free speech is important for many other reasons. Index spoke to many different experts, professors and campaigners to find out why free speech is important to them.

Index on Censorship magazine editor, Rachael Jolley, believes that free speech is crucial for change. “Free speech has always been important throughout history because it has been used to fight for change. When we talk about rights today they wouldn’t have been achieved without free speech. Think about a time from the past – women not being allowed the vote, or terrible working conditions in the mines – free speech is important as it helped change these things” she said.

Free speech is not only about your ability to speak but the ability to listen to others and allow other views to be heard. Jolley added: “We need to hear other people’s views as well as offering them your opinion. We are going through a time where people don’t want to be on a panel with people they disagree with. But we should feel comfortable being in a room with people who disagree with us as otherwise nothing will change.”

Human rights activist Peter Tatchell states that going against people who have different views and challenging them is the best way to move forward. He told Index: “Free speech does not mean giving bigots a free pass. It includes the right and moral imperative to challenge, oppose and protest bigoted views. Bad ideas are most effectively defeated by good ideas – backed up by ethics, reason – rather than by bans and censorship.”

Tatchell, who is well-known for his work in the LGBT community, found himself at the centre of a free speech row in February when the National Union of Students’ LGBT representative Fran Cowling refused to attend an event at the Canterbury Christ Church University unless he was removed from the panel; over Tatchell signing an open letter in The Observer protesting against no-platforming in universities.

Tatchell, who following the incident took part in a demonstration urging the UK National Union of Students to reform its safe space and no-platforming policies, told Index why free speech is important to him.

“Freedom of speech is one of the most precious and important human rights. A free society depends on the free exchange of ideas. Nearly all ideas are capable of giving offence to someone. Many of the most important, profound ideas in human history, such as those of Galileo Galilei and Charles Darwin, caused great religious offence in their time.”

On the current trend of no-platforming at universities, Tatchell added: “Educational institutions must be a place for the exchange and criticism of all ideas – even of the best ideas – as well as those deemed unpalatable by some. It is worrying the way the National Union of Students and its affiliated Student Unions sometimes seek to use no-platform and safe space policies to silence dissenters, including feminists, apostates, LGBTI campaigners, liberal Muslims, anti-fascists and critics of Islamist extremism.”

Article continues below

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Stay up to date on free speech” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that defends people’s freedom to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution. We fight censorship around the world.

To find out more about Index on Censorship and our work protecting free expression, join our mailing list to receive our weekly newsletter, monthly events email and periodic updates about our projects and campaigns. See a sample of what you can expect here.

Index on Censorship will not share, sell or transfer your personal information with third parties. You may may unsubscribe at any time. To learn more about how we process your personal information, read our privacy policy.

You will receive an email asking you to confirm your subscription to the weekly newsletter, monthly events roundup and periodic updates about our projects and campaigns.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Professor Chris Frost, the former head of journalism at Liverpool John Moores University, told Index of the importance of allowing every individual view to be heard, and that those who fear taking on opposing ideas and seek to silence or no-platform should consider that it is their ideas that may be wrong. He said: “If someone’s views or policies are that appalling then they need to be challenged in public for fear they will, as a prejudice, capture support for lack of challenge. If we are unable to defeat our opponent’s arguments then perhaps it is us that is wrong.

“I would also be concerned at the fascism of a majority (or often a minority) preventing views from being spoken in public merely because they don’t like them and find them difficult to counter. Whether it is through violence or the abuse of power such as no-platform we should always fear those who seek to close down debate and impose their view, right or wrong. They are the tyrants. We need to hear many truths and live many experiences in order to gain the wisdom to make the right and justified decisions.”

Free speech has been the topic of many debates in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks. The terrorist attack on the satirical magazine’s Paris office, in January 2015, has led to many questioning whether free speech is used as an excuse to be offensive.

Many world leaders spoke out in support of Charlie Hebdo and the hashtag #Jesuischarlie was used worldwide as an act of solidarity. However, the hashtag also faced some criticism as those who denounced the attacks but also found the magazine’s use of a cartoon of the Prophet Mohammed offensive instead spoke out on Twitter with the hashtag #Jenesuispascharlie.

After the city was the victim of another terrorist attack at the hands of ISIS at the Bataclan Theatre in November 2015, President François Hollande released a statement in which he said: “Freedom will always be stronger than barbarity.” This statement showed solidarity across the country and gave a message that no amount of violence or attacks could take away a person’s freedom.

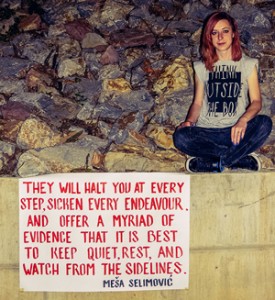

French cartoonist t0ad told Index about the importance of free speech in allowing him to do his job as a cartoonist, and the effect the attacks have had on free speech in France: “Mundanely and along the same tracks, it means I can draw and post (social media has changed a hell of a lot of notions there) a drawing without expecting the police or secret services knocking at my door and sending me to jail, or risking being lynched. Cartoonists in some other countries do not have that chance, as we are brutally reminded. Free speech makes cartooning a relatively risk-free activity; however…

“Well, you know the howevers: Charlie Hebdo attacks, country law while globalisation of images and ideas, rise of intolerances, complex realities and ever shorter time and thought, etc.

“As we all see, and it concerns the other attacks, the other countries. From where I stand (behind a screen, as many of us), speech seems to have gone freer … where it consists of hate – though this should not be defined as freedom.”

In the spring 2015 issue of Index on Censorship, following the Charlie Hebdo attacks, Richard Sambrook, professor of Journalism and director of the Centre for Journalism at Cardiff University, took the opportunity to highlight the number journalists that a murdered around the world every day for doing their job, yet go unnoticed.

Sambrook told Index why everyone should have the right to free speech: “Firstly, it’s a basic liberty. Intellectual restriction is as serious as physical incarceration. Freedom to think and to speak is a basic human right. Anyone seeking to restrict it only does so in the name of seeking further power over individuals against their will. So free speech is an indicator of other freedoms.

“Secondly, it is important for a healthy society. Free speech and the free exchange of ideas is essential to a healthy democracy and – as the UN and the World Bank have researched and indicated – it is crucial for social and economic development. So free speech is not just ‘nice to have’, it is essential to the well-being, prosperity and development of societies.”

Ian Morse, a member of the Index on Censorship youth advisory board told Index how he believes free speech is important for a society to have access to information and know what options are available to them.

He said: “One thing I am beginning to realise is immensely important for a society is for individuals to know what other ideas are out there. Turkey is a baffling case study that I have been looking at for a while, but still evades my understanding. The vast majority of educated and young populations (indeed some older generations as well) realise how detrimental the AKP government has been to the country, internationally and socially. Yet the party still won a large portion of the vote in recent elections.

“I think what’s critical in each of these elections is that right before, the government has blocked Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook – so they’ve simultaneously controlled which information is released and produced a damaging image of the news media. The media crackdown perpetuates the idea that the news and social media, except the ones controlled by the AKP, are bad for the country.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1538130760855-7d9ccb72-bf30-2″ taxonomies=”571, 986″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Oct 2015 | Campaigns, mobile, Youth Board

Lejla Becar, from Bosnia and Herzegovina, is a member of the current Index Youth Advisory board. Learn more

Index on Censorship is recruiting for its next Youth Advisory Board.

This is your chance to be associated with a media and human rights organisation, and have the opportunity to discuss freedom of expression issues you feel strongly about with Index and peers from around the world. We will give you the chance to speak to senior staff within Index or the media/human rights/arts sectors, helping you to develop your knowledge and extend your personal networks. You’ll also be assigned monthly tasks to broaden your skills and you will be featured on our website (see the current board here).

The new board will hold the position for six months from January-June 2016.

We are looking for enthusiastic young people, aged between 16-25, who must be committed to attending monthly meetings, which are held online with fellow participants. Applicants can be based anywhere in the world. We are looking for people who are communicative and who will be in regular touch with Index.

If you would like to apply, please submit a brief 200-word, blog-style piece about a current freedom of expression issue, along with your CV and covering letter to [email protected] by 5pm on Friday 4 December 2015.

Successful applicants will be contacted via email before the end of December 2015.

Find out more about the Index Youth Advisory Board below:

What is the youth board?

The youth board is a specially selected group of young people aged 16-25 who will advise and inform Index on Censorship’s work, supporting our ambition to fight for free expression all around the world and ensuring our engagement with issues relevant to tomorrow’s leaders.

Why has Index started a youth board?

Index on Censorship is committed to fighting censorship not only now, but also in future generations, and we want to ensure that the realities and challenges experienced by young people in today’s world are properly reflected in our work.

Index is also aware that there are many who would like to commit some or all of their professional lives to fighting for human rights and the youth board is our way of supporting the broadest range of young people to develop their voice, find paths to freely expressing it and potential future employment in the human rights/media/arts sectors.

What does the youth board do?

Board members meet once a month via Google Hangout to discuss the most pressing freedom of expression issues of the moment, where they will be given a monthly task to complete, and will also set that months question for our project, #IndexDrawtheLine. There is also the opportunity to get involved with events such as debates and workshops for our work with young people and events, such as our annual Index Freedom of Expression Awards and Index on Censorship magazine launches.

How do people get on the youth board?

Each youth board will sit for a term of six months. Current board members are invited to reapply up to one time. The board will be selected by Index on Censorship in an open and transparent manner and in accordance with our commitment to promoting diversity.

Meet the current Youth Advisory Board here.

23 Sep 2015 | Magazine, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by Max Wind-Cowie on free speech in politics, taken from the winter 2014 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend the Elections – live! session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

We are often, rightly, concerned about our politicians censoring us. The power of the state, combined with the obvious temptation to quiet criticism, is a constant threat to our freedom to speak. It’s important we watch our rulers closely and are alert to their machinations when it comes to our right to ridicule, attack and examine them. But here in the West, where, with the best will in the world, our politicians are somewhat lacking in the iron rod of tyranny most of the time, I’m beginning to wonder whether we may not have turned the tables on our politicians to the detriment of public discourse.

Let me give you an example. In the UK, once a year the major political parties pack up sticks and spend a week each in a corner of parochial England, or sometimes Scotland. The party conferences bring activists, ministers, lobbyists and journalists together for discussion and debate, or at least, that’s the idea. Inevitably these weird gatherings of Westminster insiders and the party faithful have become more sterilised over the years; the speeches are vetted, the members themselves are discouraged from attending, the husbandly patting of the wife’s stomach after the leader’s speech is expertly choreographed. But this year, all pretence that these events were a chance for the free expression of ideas and opinions was dropped.

Lord Freud, a charming and thoughtful – if politically naïve – Conservative minister in the UK, was caught committing an appalling crime. Asked a question of theoretical policy by an audience member at a fringe meeting, Freud gave an answer. “Yes,” he said, he could understand why enforcing the minimum wage might mean accidentally forcing those with physical and learning difficulties out of the work place. What Freud didn’t know was that he was being covertly recorded. Nor that his words would then be released at the moment of most critical, political damage to him and his party. Or, finally, that his attempt to answer the question put to him would result in the kind of social media outrage that is usually reserved for mass murderers and foreign dictators.

Why? He wasn’t announcing government policy. He was thinking aloud, throwing ideas around in a forum where political and philosophical debate are the name of the game, not drafting legislation. What’s more, the kind of policy upon which he was musing is the kind of policy that just a few short years before disability charities were punting themselves. So why the fuss?

It’s not solely an issue for British politics. Consider the case of Donald Rumsfeld. Now, there’s plenty about which to potentially disagree with the former US secretary of state for defense – from the principles of a just war to the logistics of fighting a successful conflict – but what is he most famous for? Talking about America’s ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, he thought aloud, saying “because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know.” The response? Derision, accompanied by the sense that in speaking thus Rumsfeld was somehow demonstrating the innate ignorance and stupidity of the administration he served. Never mind that, to me at least, his taxonomy of doubt makes perfect sense – the point is this: when a politician speaks in anything other than the smooth, scripted pap of the media relations machine they are wont to be crucified on a cross of either outrage, mockery or both. Why? Because we don’t allow our politicians to muse any longer. We expect them to present us with well-polished packages of pre-spun, offence-free, fully-formed answers packed with the kind of delusional certainty we now demand of our rulers. Any deviation – be it a “U-turn”, an “I don’t know” or a “maybe” – is punished mercilessly by the media mob and the social media censors that now drive 24-hour news coverage.

Let me be clear about what I don’t mean. I am not upset about “political correctness” – or manners, as those of us with any would call it – and I am not angry that people object to ideas and policies with which they disagree. I am worried that as we close down the avenues for discussion, debate and indeed for dissent if we box our politicians in whenever they try to consider options in public – not by arguing but by howling with outrage and demanding their head – then we will exacerbate two worrying trends in our politics.

First, the consensus will be arrived at in safe spaces, behind closed doors. Politicians will speak only to other politicians until they are certain of themselves and of their “line- to-take”. They will present themselves ever more blandly and ever less honestly to the public and the notion that our ruling class is homogenous, boring and cowardly will grow still further.

Which leads us to a second, interrelated consequence – the rise of the taboo-breaker. Men – and it is, for the most part, men – such as Nigel Farage and Russell Brand in the UK, Beppe Grillo in Italy, Jon Gnarr in Iceland, storm to power on their supposed daringness. They say what other politicians will not say and the relief that they supply to that portion of the population who find the tedium of our politics both unbearable and offensive is palpable. It is only a veneer of radicalism, of course – built often from a hodge-podge of fringe beliefs and personal vanity – but the willingness to break the rules captures the imagination and renders scrutiny impotent. Where there are no ideas to be debated the clown is the most interesting man in the room.

They say we get the politicians we deserve. And when it comes to the twin plaques of modern politics you can see what they mean. On the one hand we sit, fingers hovering over keyboards, ready to express our disgust at the latest “gaffe” from a minister trying to think things through. On the other we complain about how boring, monotonous and uninspiring they all are, so vote for a populist to “make a point”. Who is to blame? We are. It is time to self-censor, to show some self-restraint, and to stop censoring our politicians into oblivion.

© Max Wind-Cowie and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas, featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the winter 2014 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

4 Jun 2015 | Events

Photo: Thomson Reuters Foundation

Six months after the Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris, journalists face more threats than ever before, from harassment to imprisonment to murder – since the beginning of the year, 50 journalists have been killed.

While some countries, like Norway, have scrapped blasphemy laws to strongly assert freedom of speech, others such as the UK are increasing state surveillance and censorship to “protect citizens from violence”. How can international law protect journalists in this challenging and unique context? Is it possible to strike a balance between security concerns and freedom of expression? Is the right to free speech an absolute one?

Join the Thomson Reuters Foundation, Reporters Without Borders and Paul Hastings LLP for a panel debate featuring:

- John Lloyd, Reuters Institute and Financial Times

- Prof Timothy Garton Ash, Oxford University

- Sylvie Kauffmann, Le Monde

- William Bourdon, Paris Bar and Association Sherpa

- Jodie Ginsberg, Index on Censorship

When: Monday 29 June, 6:00pm (followed by drinks reception & canapés)

Where: Edelman, London, SW1E 6QT (Map/directions)

Tickets: Free, book here

#FreeSpeechDebate