3 May 2016 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

February 4, 2013. Recep Tayyip Erdogan during a press conference in Prague.

With conditions worsening on a daily basis, Turkey now risks total blackout on public debate.

Punitive measures and harsh restrictions have diminished the domain for free and independent journalism, and media pluralism is showing strong signs of total collapse.

As Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project highlights in its latest quarterly report, the country experienced a large number of media freedom violations.

“Over half of the arrests [in the first quarter of 2016] occurred in Turkey when journalists were reporting on violence or protests in the country,” the report said. “The data indicates a pattern where arrests are launched on terror charges or taking place during anti-terror operations.”

In its latest World Press Freedom Index, scrutinising media in 180 countries, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) ranked Turkey as #151, marking yet another fall, this time by two positions.

“President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has embarked on an offensive against Turkey’s media. Journalists are harassed, many have been accused of ‘insulting the president’ and the internet is systematically censored,” RSF said in its findings.

The decline was even more dramatic in the annual Freedom of the Press 2016 survey by Freedom House. Its survey over the past year marked a fall by six points, placing Turkey as 156th among 199 countries, again among those as “not free”.

“The government, controlled by Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), aggressively used the penal code, criminal defamation legislation, and the country’s antiterrorism law to punish critical reporting, and journalists faced growing violence, harassment, and intimidation from both state and non-state actors during the year. The authorities continued to use financial and administrative leverage over media owners to influence coverage and silence dissent,” it concluded.

This downfall is unprecedented in intensity. The country’s remnant core of brave, free and independent journalists, regardless of their political views, now agree that free journalism will soon cease to exist in Turkey. With full-frontal attacks on the media, the sector may become subservient to the political and bureaucratic power, with content rife with stenography and propaganda.

Legal inquiries and charges against journalists are continually on the rise. According to the ministry of justice, the number of “insulting the president” cases passed 1,800 since mid-2014.

In other cases, such as the charges brought against Cumhuriyet daily, its editors Can Dündar and Erdem Gül are accused of spying and treason, for printing news stories about lorries carrying weapons, allegedly to Syrian jihadist groups, by the government’s orders.

In another notorious case, investigative journalist Mehmet Baransu has been detained for over 13 months over his inquiries into the alleged abuses of power within the military.

In a fresh case, two senior journalists from Cumhuriyet, Ceyda Karan and Hikmet Çetinkaya, were sentenced to two years each in prison for “inciting hatred”. Their “crime” was to reprint the Charlie Hebdo front page cartoon in their column, which they said was an act of professional solidarity.

According to Bianet, a monitoring site, there are now 28 journalists in Turkish prisons, many of whom are affiliated with the Kurdish media, based on charges brought under anti-terror laws.

The draconian nature of charges and prison sentences leave little doubt about AKP government’s intent to criminalise journalism as a whole.

Punitive measures against journalism go far beyond court cases. The most efficient method has proven to be firing journalists who insist on exercising basic standards of the profession.

Since mid-2013, following Gezi Park protests, 3,500 journalists have lost their jobs. Media moguls have come under increasing pressure from the government, which demands action or threatens to cancel lucrative public contracts. Taking advantage of the low influence of trade unions (fewer than 4% of journalists are members), employers axe staff arbitrarily.

As a result of this widespread exercise in conglomerate-dominated “mainstream media”, with newsrooms turned into “open-air prisons”, self-censorship in Turkey has become a deeply rooted culture. Blacklists have been drawn up of TV pundits and columnists in the press, who are known for critical stands, no matter their political leaning.

What apparently weighed heavy in the gloomy figures by Index on Censorship, RSF and FH is the fact that, from early last year, authorities started also targeting large, private media institutions, known for critical journalism.

Hürriyet, an influential newspaper belonging to Doğan Media was attacked by a mob two nights in a row last summer, after which its owners felt they had to “tone down” critical content.

In even more dramatic cases, Koza-Ipek Media outlets were raided by the police last autumn, followed some months later by a similar large-scale operation against Zaman Media, second largest group in the sector, and the largest independent news agency, CHA.

These seizures, along with some other critical channels yanked off satellite and digital platforms in recent months, left a huge vacuum, threatening to terminate the diversity of the media.

Now, with around 90% of the sector under direct or indirect editorial control of the AKP government, including the state broadcaster TRT, there are only three critical TV channels and no more than five small-scale independent newspapers left.

As a result of these assaults, two things are apparent: firstly, investigative journalism is blocked and news is severely filtered; secondly, with diversity fading out, public debate, a key aspect of any democracy, is severely limited.

Along with routine bans on reporting on specific events such as terror attacks, severe accreditation restrictions and a newly emerging pattern of deporting international media correspondents, the conclusion is inevitable.

A profession faces extinction and along with its exit, and a thick wall between the truth and the public, both domestic and international, is emerging. This total collapse will have far deeper consequences than anyone can imagine.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

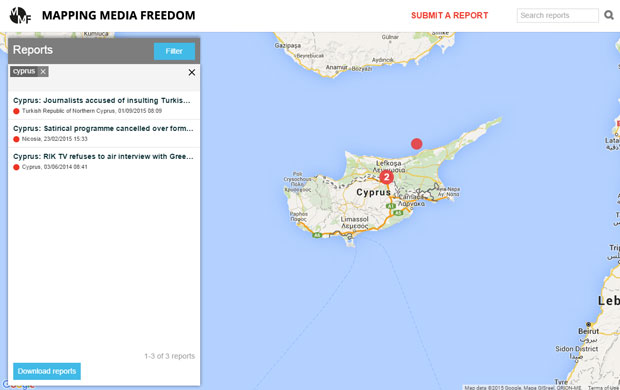

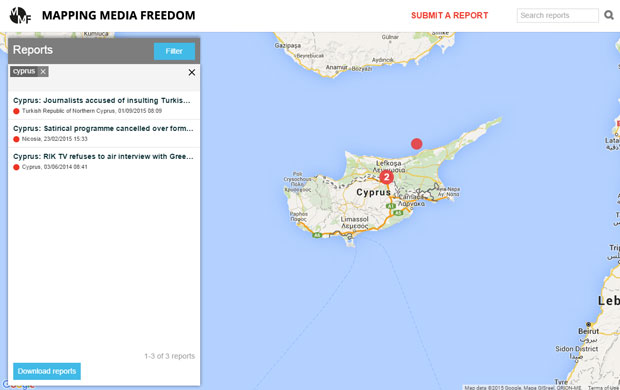

19 Nov 2015 | Cyprus, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News

Turkish Cypriot daily Afrika reported on 30 August 2015 that the Turkish military forces in Cyprus had accused the paper of being against “the army and the flag”. Afrika’s articles had allegedly offended Turkish forces and made “people alienated from the army”, according to the case.

Editor-in-chief Sener Levent and writer Mahmut Anayasa, both of whom had shared an Afrika article from July on social media, were called to the prosecutor’s office for questioning. According to Costas Mavridis, a Greek Cypriot Member of the European Parliament, this is not the first time Levent has faced accusations. Both were later released.

After the questioning of Levent and Anayasa, Mavridis asked the European Commission about what actions are to be taken in order to protect the two European citizens.

“This action is clearly against human rights, specifically freedom of expression,” Mavridis said. He added that the only way for them to be safe is by making their case known to international and European public opinion, which is why he is proposing that Levent should be the Cypriot candidate for the European Citizen Prize 2015. “Sener Levent’s uninterrupted struggle for freedom of expression is a brave stance in favour of fundamental principles of the European culture at the risk of his life,” Mavridis said.

Yurdakul Cafer from the Association of Turkish Cypriot Journalists, speaking to Index on Censorship, stressed that, “media and the press in Northern Cyprus enjoy freedom of expression to a large degree”.

Before the opening of Afrika, Levent was to be the editor-in-chief of one of the first pro-European newspapers in Northern Cyprus, Avrupa, which means “Europe” in Turkish. According to a statement by the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) from November 2000, the daily Avrupa was firebombed. “Extensive damage was caused and the printing house is no longer operating,” according to statement.

The IFJ had also noted that the attack “followed a period of court fines and official harassment designed to try to close down the newspaper”. Levent and other journalists were at the centre of these legal measures. As a result, the newspaper folded and was replaced by Afrika few years later.

The 2014 Freedom House report states that overall the situation of the media in Northern Cyprus is “free”. “Some media outlets are openly critical of the government,” it writes, although “in recent years some journalists who espouse anti-government positions were physically attacked, apparently by members of nationalist groups”.

“There were no such incidents in 2013,” the report concluded.

Cafer, who is also a news editor at Bayrak Radio Television, said that “despite Ankara’s strong political and military presence in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, Turkish Cypriot newspapers, TV and radio stations are exceptionally democratic and open to discuss sensitive public, social and economic issues”.

The 2015 World Press Freedom Index placed the territory at 76 for media freedom in the world. Cyprus was ranked 24 in the world for press freedom. Turkey, which Northern Cyprus depends on, ranked 149 and continues to have high levels of violations against media, according to verified reports logged to Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project.

Cafer said that Levent “was taken to court on charges of espionage but the charges brought against him were not for what he wrote,” adding that “he has been released”. “If there is no trial or if you are not jailed then I don’t think that’s persecution. There is no pressure or persecution in TRNC,” Cafer said, claiming that a lot has changed since the 1996 assassination of Kutlu Adali.

Adali, a journalist for the Northern Cypriot newspaper Yeni Duzen, was fatally shot outside his home. According to Mavridis, before Adali’s assassination he had announced his willingness to reveal some facts about the government’s immigration policies, specifically the Turkish settlers in Northern Cyprus. “Adali’s murder was a dark chapter in this country’s history, but there is no other incident like this one and that Turkey or TRNC does not exist anymore,” Cafer told Index on Censorship.

Overall, Cafer is optimistic about the future of media freedom in Northern Cyprus, while he points out that “the biggest problem and threat to peace and reconciliation in Cyprus” could be “online media”. “Many online news outlets,” he explained, “have popped up and many of them disregard the main principles of journalism or any code of ethics, spreading misinformation or doing more harm than good. I think we need more legislation that protects good journalism, not legislation that curtails freedoms,” he concluded.

However, Mavridis, using a phrase from another Turkish Cypriot journalist, who was prosecuted and threatened many times in the past, stresses that “even when a bird flies in Northern Cyprus, it’s with the permission or the tolerance of the manager of the Turkish occupying forces”.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

This article was posted on 18 November 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

2 May 2014 | News

A London protest calling for the release of jailed Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt (Image: Index on Censorship)

Press freedom is at a decade low. Considering just a handful of the events of the past year — from Russian crackdowns on independent media and imprisoned journalists in Egypt, to press in Ukraine being attacked with impunity and government reactions to reporting on mass surveillance in the UK — it is not surprising that Freedom House have come to this conclusion in the latest edition of their annual press freedom report. This serves as a stark reminder that press freedom is a right we need to work continuously and tirelessly to promote, uphold and protect — both to ensure the safety of journalists and to safeguard our collective right to information and ability to hold those in power to account. On the eve of World Press Freedom day, we look back at some of the threats faced by the world’s press in the last 12 months.

1) Journalism is not terrorism…

National security has been used as an excuse to crack down on the press this year. “Freedom of information is too often sacrificed to an overly broad and abusive interpretation of national security needs, marking a disturbing retreat from democratic practices,” say Reporters Without Borders (RSF) in their recently released 2014 Press Freedom Index.

Journalists have faced terrorism and national security-related accusations in places known for their somewhat chequered relationship with press freedom, including Ethiopia and Egypt. However, the US and the UK, which have long prided themselves on respecting and protecting civil liberties, have also come under criticism for using such tactics — especially in connection to the ongoing revelations of government-sponsored mass surveillance.

American authorities have gone after former NSA contractor and whistleblower Edward Snowden, tapped the phones of Associated Press staff, and demanded that journalists, like James Risen, reveal their sources. British authorities, meanwhile, detained David Miranda under the country’s Terrorism Act. Miranda is the partner of Glenn Greenwald, the journalist who broke the mass surveillance story. Authorities also raided the offices of the Guardian — a paper heavily involved in reporting in the Snowden leaks.

2) …but governments still like putting journalists in prison

The Al Jazeera journalists detained in Egypt on terrorism-related charges was one of the biggest stories on attacks on press freedom this year. However, Mohamed Fahmy, Baher Mohamed, Peter Greste and their colleagues are far from the only journalists who will spend World Press Freedom Day behind bars. The latest prison census from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) put the number of journalists in jail for doing their job at 211 — their second highest figure on record.

In Bahrain, award-winning photographer Ahmed Humaidan was sentenced in March to ten years in prison. In Uzebekistan, Muhammad Bekjanov, editor of opposition paper Erk, is serving a 19-year sentence — which was increased from 15 in 2012, just as he was due to be released. In Turkey, after waiting seven years, Fusün Erdoğan, former general manager of radio station Özgür Radyo, was last November sentenced to life in jail. Just last Friday, Ethiopian authorities arrested prominent political journalist Tesfalem Waldyes and six bloggers and activists.

3) New media is under attack…

As more journalism is being conducted online, blogs, social and other new media are increasingly being targeted in the suppression of press freedom. Almost half of the world’s jailed journalists work for online outlets, according to the CPJ. China — with its massive censorship apparatus — has continued censoring microblogging site Sina Weibo, while also turning its attention to relative newcomer WeChat. In March, it closed down several popular accounts, including that of investigative journalist Luo Changping.

Meanwhile, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has publicly all but declared war on social media, at one point calling it the “worst menace to society”. Twitter played a big role in last summer’s Gezi Park protests, used by journalists and other protesters alike. Only days ago, Turkish journalist Önder Aytaç was jailed, essentially, because of the letter “k” in a Tweet.

Meanwhile Russia has seen a big crackdown on online news outlets, while legislation recently passed in the Duma is targeting blogs and social media.

4) …and independent media continues to struggle

Only one in seven people in the world live in countries with free press. In many parts of the world, mainstream media is either under tight control by the government itself or headed up media moguls with links to those in power, with dissenting voices within news organisation often being pushed out. Brazil, for instance, has been labelled “the country of 30 Berlusconis” because regional media is “weakened by their subordination to the centres of power in the country’s individual states”. At the start of the year, RIA Novosti — known for on occasion challenging Russian authorities — was liquidated and replaced by the more Kremlin-friendly Rossiya Segodnya (Russia Today), while in Montenegro, has seen efforts by the government to cut funding to critical media. This is not even mentioning countries like North Korea and Uzbekistan, languishing near the bottom of press freedom ratings, where independent journalism is all but non-existent.

5) Attacks on journalists often go unpunished

A staggering fact about the attacks on journalists around the world, is how many happen with impunity. Since 1992, 600 journalists have been killed. Most of the perpetrators of those crimes have not been brought to justice. Attacks can be orchestrated by authorities or by non-state actors, but the lack of adequate responses by those in power “fuels the cycle of violence against news providers,” says RSF. In Mexico, a country notorious for violence against the press, three journalists were murdered in 2013. By last October, the state public prosecutor’s office had yet to announce any progress in the cases of Daniel Martínez Bazaldúa, Mario Ricardo Chávez Jorge and Alberto López Bello, or disclose whether they are linked to their work. Pakistan is also an increasingly dangerous place to work as a journalist. Twenty seven of the 28 journalists killed in the past 11 years in connection with their work have been killed with impunity. Syria, with its ongoing, devastating war, is the deadliest place in the world to be a journalist, while some of the attacks on press during the conflict in Ukraine, have also taken place without perpetrators being held accountable. That attacks in the country appear to be accelerating, CPJ say is “a direct result of the impunity with which previous attacks have taken place”.

This article was published on May 2, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Oct 2013 | Digital Freedom, News, Politics and Society

Photo: Flickr user Secretary of Defense

A threat to press freedom is an assault on our right to know.

A new report from the Committee to Protect Journalists tries to capture the invisible impact of the Obama administration’s troubled relationship with the press. The report, authored by Leonard Downie Jr., former executive editor of the Washington Post, and CPJ’s Sara Rafsky, is the most comprehensive look at how the Obama administration’s actions have deeply damaged press freedom and the public’s access to information.

For those who have followed the administration’s policies, court cases and actions related to leaks and the press, the report doesn’t contain a lot of new information. What it does is weave together each of the cases and strategies the administration has pursued, surfacing key themes and illustrating that these examples are not aberrations, but part of a coordinated strategy. Presenting this bigger picture reframes the debate over press freedom in America and reminds us that it’s not enough to tinker around the edges; we need to demand a major course correction.

The report covers the administration’s leak investigations and policies, its surveillance programs, its secrecy and the use of its own media channels to evade “scrutiny by the press.”

All of this is punctuated by the interviews Downie conducted with journalists. Hearing from journalists in their own words, about the challenges they’ve faced and the concerns they have, brings home the seriousness of the crisis in press freedom.

New York Times National Security Reporter Scott Shane captured it best when he told Downie that sources are now “scared to death” to even talk about unclassified, everyday issues.

“There’s a gray zone between classified and unclassified information, and most sources were in that gray zone. Sources are now afraid to enter that gray zone,” Shane said. “It’s having a deterrent effect. If we consider aggressive press coverage of government activities being at the core of American democracy, this tips the balance heavily in favor of the government.”

That shifting balance of power is one of the critical takeaways from the CPJ report. Through efforts like NSA surveillance, the Justice Department’s seizure of phone and email records, and the “Insider Threat Program,” which encourages federal employees to monitor the behavior of their colleagues, the Obama administration has marshaled institutional resources toward efforts that erode press freedom and challenge newsgathering.

“The administration’s war on leaks and other efforts to control information are the most aggressive I’ve seen since the Nixon administration,” Downie writes. “The 30 experienced Washington journalists at a variety of news organizations whom I interviewed for this report could not remember any precedent.”

The report is an important addition to the debate about press freedom, but the scope of its inquiry is limiting. In focusing on the Obama administration, Downie examines in depth the various cases of journalists who have been caught up in federal investigations and the actions of federal agencies only.

As such, the report is not a full accounting of the state of press freedom today. A more comprehensive analysis of troubling state bills, worrisome court cases and the alarming spike in journalist arrests and harassment by local police would give a fuller picture.

In addition, the journalists implicated in the cases Downie reports on are all from mainstream media organizations like the Associated Press, Fox News and the New York Times, and most of his interviews are with Washington editors and reporters from major newsrooms. But the Obama administration’s adversarial relationship with the press has also impacted smaller newsrooms, freelance journalists, independent bloggers and citizen journalists.

The Committee to Protect Journalists has led the way in looking at the impact of threats to press freedom and freedom of expression on digital journalists and citizen reporters abroad. This report should be a starting place for the CPJ to assess the threats and challenges facing all kinds of journalists in the U.S.

It’s notable that, in its recommendations at the end of the report, CPJ calls on the Obama administration to “advocate for the broadest possible definition of ‘journalist’ or ‘journalism’ in any federal shield law.” The law, the CPJ says, must “protect the newsgathering process, rather than professional credentials, experience, or status, so that it cannot be used as a means of de facto government licensing.”

While the CPJ focuses here on the need for a shield law, this recommendation should apply to any law or guideline the administration implements. The shield law is important not only for how it defines a journalist but also for the precedent it could set for future press freedom decisions.

The CPJ also advocates for ensuring that journalists won’t be prosecuted for receiving or reporting on leaks, ending the use of the Espionage Act to prosecute those who leak information to the press, improving transparency about NSA surveillance, enforcing revised Justice Department guidelines, ending the use of overly broad secret subpoenas, and strengthening the administration’s adherence to the Freedom of Information Act.

It’s remarkable that we have to ask for these basic protections and reassurances from our government, but the CPJ report makes it clear that we can’t take press freedom for granted. This report should be a starting point for a much larger discussion that brings together journalists of all kinds, policymakers and everyday Americans to talk through the challenges, questions and concerns about press freedom.

We’re facing a fundamental and coordinated shift in how our government and press interact — and it’s not enough to respond to each attack in isolation. We need to launch a proactive effort to reassert the centrality of a free press in our democracy.

This article was originally published at FreePress.net and is republished here by permission.