27 Mar 2019 | Magazine, Volume 48.01 Spring 2019

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Worrying about a local newspaper closing or reporters being centralised is not just nostalgia, it’s being concerned that our democratic watchdogs are going missing, says Rachael Jolley in the spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

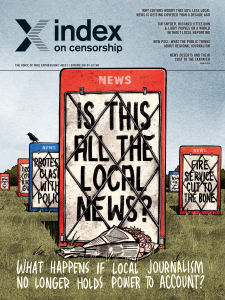

Is this all the local news? The spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Regional daily newspaper the Eastern Daily Press is closing two of its district offices, in Cromer on the north Norfolk coast, and in Diss, a Norfolk market town.

This matters to me because the EDP was the first place I worked as a journalist and it was then one of the UK’s biggest local papers, with at least 10 offices, all employing reporters. Some of the offices had one or two reporters, some had 10, and the Norwich head office had about 50 editorial staff. When I joined as a trainee reporter, the big bosses mandated that we worked in at least three different offices within two years. We went out and about on an almost daily basis, talking to people and covering events. These days, national newspaper editors dream of having as many reporters as the EDP had in the 1990s.

So why does this matter? And should anyone care when the small newspaper office in Cromer closes? After all, as the management of the EDP said, everyone is online now, so we can do business digitally. And, yes, most of us can communicate by email and we could email our news tips to a far-flung newsdesk.

We could, but perhaps we won’t bother.

And, yes, you can do business digitally: we can send money and adverts around the world at the click of a mouse. But the stuff at the guts of a local newspaper, the finding out what is going on and hearing a sniff of a story in the pub, will that still go on or will reporters be left to depend on social media as a source?

If no local reporters are left living and working in these communities, are they really going to care about those places? Will they even know who to call, or who to email?

When a massive fire starts down by the King’s Lynn docks, will anyone from the local newspaper be there to see it (as I was one midnight when I saw the flames out of my bedroom window)?

The answer is clearly that they will not. News will go unreported; stories will not be told; people will not know what has happened in their towns and communities.

Local newspapers (and, to some extent, local radio stations) were, and in some places still are, fighting for the little guy against the monolith for the old person, say, who is inundated by noisy construction work morning, noon and night. They bring to the attention of the public a council plan to close a massively popular library, or a bid to cement over a local swimming pool and turn it into flats. They cover a big crown court case about a million-pound corruption that ends with shops closing and jobs being lost.

When things went wrong, the local media were there to make sure people knew about it, and what the problems were. They could knock on the door of the powerful and shout for something to change.

And, yes, these things don’t have to be done only in print – a website can still cover stories and reach an audience – but if there are no reporters on the ground, and they are increasingly based far away from the stories they cover, they will increasingly miss knowing about scandals, corruption and the death of the totally brilliant grandmother who was the heart of the place.

One ex-newspaperman told me he recently walked into a city office to find all the staff for local newspapers from one part of Scotland sitting there, together. They had all become long-distance reporters, at arm’s length from the places they reported on.

This is more than an industrial tipping point. This is a gradual unpicking of part of democracy: scandals that need to be held up to the light will get missed; local authorities that spend public money will have no one watching to see if they are doing it according to the rules.

There is also cause to worry about the coverage of the courts and the justice system. As the former lord chief justice of England and Wales, Lord Judge, told Index: “Open justice is one of the essential safeguards of the rule of law. The presence of the media in our courts represents the public’s entitlement to witness the administration of justice and assess whether, and how, justice is being done. As the number of newspapers declines and fewer journalists attend court, particularly in courts outside London and the major cities, and except in high-profile cases, the necessary public scrutiny of the judicial process will be steadily eroded, eventually to virtual extinction.”

Lord Judge is right. It is likely that budget-stretched local newspaper managers will drop the coverage that costs them the most money. The difficult stuff will get ignored and replaced with fun videos of cats and other animals. The person who sifts steadily through a council agenda, page by page, will disappear, to be replaced by a “content manager” whose job is to produce crowd-pleasing clickbait fare.

Mike Sassi, editor of the Nottingham Post in the UK, said: “There’s no doubt that local decision-makers aren’t subject to the level of scrutiny they once were. There are large numbers of councils right across the country making big decisions, involving millions of pounds of public money, who may never see a local reporter. Many local authorities will be operating in the knowledge that no one will ever ask them an awkward question. Which, obviously enough, does nothing to help build trust in local democracy.”

The problem, some argue, is that the public are not really bothered about losing these skills or services. If they were, they would be willing to support them. Local news has to be paid for, and the companies that have been producing it have to make money to survive. If the public don’t care enough to pay for it, they will move on to doing other things. That’s the way the market works.

People are willing to pay for a cinema ticket, or to go to the football, or for a Netflix subscription, but right now it appears that not many are willing to pay for local news. And if no one funds it, it disappears. Will it be a case of appreciating local news reporting only when it is gone?

There’s even more to worry about when it comes to news vacuums appearing. As people feel more and more disconnected from the place where they live, they move into a state of solitude, not knowing what is going on around them. That breeds discontent, a feeling of being ignored, and when a community doesn’t exist there’s no one to lean on when things go wrong.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Proper journalism cannot be replaced by people tweeting their opinions and the occasional photo of a squirrel, no matter how amusing the squirrel might be” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

There is a public right to information about what locally elected officials are doing, but there is no public right to a newspaper.

If no one wants to buy it, and if no one cares about it, it is likely to disappear. But there is a lot more to lose than a place when you find detailed coverage of your local football team (much appreciated though that is by many). There are deep societal costs.

There are some signs of public discontent which may be linked to declining local news coverage, and might be a sign that people are waking up to what is going missing when local media operations close down or pull away from certain types of coverage.

For this issue, we commissioned YouGov to carry out a poll of the public and we found that 40% of British adults over the age of 65 think that the public know less about what is happening in areas where local newspapers have closed down.

Also, Libby Purves, a columnist at The Times who started her career on a local radio station, tells us she believes part of the discontent that produced Brexit was about people in far-flung places and regional cities feeling their news and views were being ignored. She also talks to us about her earlier years working on Radio Oxford and the close relationship the station had with people who worked in and around the city. They would march into the centrally located studio and tell reporters when they were getting it wrong, she says.

The question is: how can that be replaced today? Can it be done on social media, for instance? Or is it a bit like barking at a tree? You have made noise, but the tree definitely isn’t listening?

For those of you who thought that threats to local news were just in your own country, think again. We looked into this issue around the globe and found some of the same problems developing in China, Argentina, the USA and Belgium, among others. We interviewed people in Italy, Germany, India, the UK and Nigeria. The worries are often the same, the reasons slightly different.

Many of those who fight for freedom of expression feel that declining numbers of local reporters just make it easier for governments to cover up scandals, leave the public ill-informed, and make sure only the information they want is out there.

There are some bright sparks who have ideas about how the important services that local news has provided could work differently in the future. There are people starting their own local paper, focusing on digging out stories, growing circulation and making enough money to keep going.

Other ideas are also emerging. The BBC’s local democracy reporters project, discussed in this magazine, is one way of funding specialists who have time to dig through council agendas to find out what is going on. What about finding specialist bloggers with in-depth knowledge on their particular local magistrates’ court, for instance, and having a Gofundme campaign to get up to 3,000 locals to pay £5 or £10 a month for a twice-weekly email of fabulously detailed and incisive analysis of what is happening?

Big ideas are needed. Democracy loses if local news disappears. Sadly, those long-held checks and balances are fracturing, and there are few replacements on the horizon. Proper journalism cannot be replaced by people tweeting their opinions and the occasional photo of a squirrel, no matter how amusing the squirrel might be.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor of Index on Censorship. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on local news

Index on Censorship’s spring 2019 issue is entitled Is this all the local news? What happens if local journalism no longer holds power to account?

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Is this all the local news?” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F03%2Fmagazine-is-this-all-the-local-news%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine asks Is this all the local news? What happens if local journalism no longer holds power to account?

With: Libby Purves, Julie Posetti and Mark Frary[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”105481″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/03/magazine-is-this-all-the-local-news/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Mar 2019 | Academic Freedom, News, Turkey

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]UPDATE: Prof. Zübeyde Füsun Üstel, whose 1 year and 3 months prison sentence was upheld on 25 February 2019, is due to begin her prison sentence within ten days, Frontline Defenders reported on 30 April 2019.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Zübeyde Füsun Üstel

A Turkish academic, who was given a 15-month jail sentence for signing a petition calling for peace in south-east Turkey, has had her sentence upheld and now faces prison. She is likely to be the first academic to be imprisoned for signing the petition.

Zübeyde Füsun Üstel’s 15-month jail sentence, originally imposed in April 2018 for signing a petition drafted by Academics for Peace, was upheld by the Turkish Court of Appeals on 25 February 2019. Üstel is a retired professor from Galatasaray University in Istanbul.

This decision by the appellate court means that she is in danger of being imprisoned very soon.

The peace petition — We Will Not Be a Party To This Crime — was initially signed by 1,128 academics and grew to 2,020 in the weeks after it was released in January 2016. Since then, the signatories have been subjected to a range of actions against them, including criminal and administrative investigations, detention, dismissals and revocation of their passports. As of December 2017, more than 400 academics have been dismissed and hundreds of PhD students have lost their scholarships.

Academics for Peace is an organisation of university professors and graduate students who drafted and launched the petition, which denounced the human rights violations committed by the government in the Kurdish regions of Turkey, demanded access to these areas for independent national and international observers, and called for a lasting peace to be secured.

“I think Professor Fusun Üstel’s case is a new illustration of the criminalisation of free speech in present-day Turkey,” said Noemi Levy-Aksu, an academic for peace whose case is still pending.

Üstel was the first academic to refuse the legal provision the courts offer when prison sentences are less than two years. The provision involves suspending the pronouncement of judgment for a period of five years, during which the defendant is supposed to refrain from committing further “crimes”. Since what constitutes a crime in Turkey can be arbitrarily changed or determined by the political establishment, this provision aims to discipline defendants by placing them under supervision by the government. However, the advantage to the provision is that the suspect is left with no criminal record, barring their good behavior.

In her court hearing in April 2018, Üstel refused the offer of a suspension and was consequently sentenced to 15 months in prison. She appealed, but it was rejected on 25 February. She could become the first academic to be imprisoned since the trials began in December 2017. Nine other academics have refused the suspension provision and are waiting to appear before the court of appeals, according to the Academics for Peace website.

Following the confirmation of Üstel’s sentence, new initiatives have been started to raise awareness about her and all of the other Academics for Peace cases.

“An open letter has been endorsed by Academics for Peace-US and UK, academic and human rights organisations and more than 1500 academics from all around the world. Other initiatives are ongoing, especially in Germany, France, the US and the UK, where many academics from Turkey are now based,” said Levy-Aksu.

Investigations were opened by the government individually against each petition signatory on charges of “conducting propaganda for a terrorist organisation.” This is the charge professor Üstel is currently facing, as per the Article No. 7/2 of the Anti-Terror Law No. 3713.

Some judges, including one dissenting judge in Üstel’s appeal case, believe the academics should not be tried under the anti-terror law on the charge of propagandizing for a terrorist organisation. Instead, they argue that Üstel’s and other cases should be considered as per the Article 301 of the Turkish penal code on the charge of “degrading the state of the republic of Turkey”.

“From the beginning, the trial of the Academics for Peace relied on very shaky grounds, both in terms of procedure and substance. The inconsistency of the decisions taken by the different courts show the arbitrariness of the process. Verdicts have been erratic and varied from 15 to 36 months imprisonment,” said Levy-Aksu.

Almost 600 of the signatories are currently undergoing trials on grounds of engagement in “propaganda for a terrorist organisation.”

Üstel published a series of articles in Turkey-based and international journals of social sciences. Her articles have mostly focused on the history of Turkey, nationalism and issues of identity.

Since its founding in 2012, Academics for Peace has organised different actions to highlight attacks on the Kurds in south-east Turkey, and to call for the Turkish government to change its policy towards the Kurds. In 2012 it issued a statement showing support for Kurdish prisoners’ demands for peace in Turkey. This statement was signed by 264 academics from over 50 universities.

Since January 2016 when they published the peace petition, the Academics for Peace case has remained a symbol of the ongoing crackdown on the right to protest and speak out against the government in Turkey.

“In the current circumstances this will highly depend on governmental policy. The other venue to challenge the decision is the European Court of Human Rights, before which several applications have already been brought,” said Levy-Aksu.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1556799978592-db3cfbd5-6c56-0″ taxonomies=”7355, 8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Mar 2019 | China, India, Magazine, News, South Africa, United Kingdom, Volume 48.01 Spring 2019, Volume 48.01 Spring 2019 Extras, Zimbabwe

Is this all the local news? We discuss this in the latest podcast. In the spring 2019 edition of Index on Censorship magazine, we explore what happens when the local news media is not there to hold power to account. Guests on this edition of the podcast are all featured in the latest magazine. Beijing-based reporter Karoline Kan, who writes for this issue, explores whether China’s social credit system could impact local journalism; Ian Murray, director of the Society of Editors, discusses a new survey where local editors talk about their fears for the future; co-founder of the Bishop’s Stortford Independent Sinead Corr talks about how she recently launched a new and successful local paper; plus in a special segment current Index youth board members Arpitha Desai, hailing from India, and Melissa Zisengwe, originally from Zimbabwe but now living in South Africa, talk about the strengths and weaknesses of community news in their countries.

Print copies of the magazine are available on Amazon, or you can take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpetine Gallery and MagCulture (all London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool). Red Lion Books (Colchester) and Home (Manchester). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

The Spring 2019 podcast can also be found on iTunes.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]