Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Presenting the world premiere of a collection of 12 explosive political five minute plays by writers including Mark Ravenhill, Neil LaBute and Caryl Churchill.

Arising from events and decisions relating to The Underbelly and Incubator Theatre’s The City, Exhibit B and the Barbican, and The Tricycle Theatre.

Each performance will include all twelve five minute plays and a lively post-show discussion exploring freedom of expression in UK arts today. Engage in discussion with the commissioned writers and a range of free expression advocates .

The post-show debate on on Friday 30th January will feature Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

WHERE: Theatre Delicatessen, London, EC1R 3ER

WHEN: Monday 26th – Saturday 31st January, 7:30pm & Sat Matinee

TICKETS: £15 / £12 – available here

This event is produced by Offstage Theatre, in association with Theatre Uncut, and supported by Index on Censorship and Free Word.

Index on Censorship’s project to map media violations in the European Union and candidate countries has recorded 74 incidents in Turkey since May 2014.

Richard Howitt MEP is foreign affairs spokesperson for both the Labour Party and the Socialist and Democrat Group in the European Parliament and is a member of its joint parliamentary committee with the Turkish Parliament

As millions mourn the shooting of journalists in France, the European Parliament convening this week in Strasbourg today extended the fight for freedom of expression to legal threats, harassment and character assassination against free journalism in Turkey.

Indeed last weekend’s scenes reminded me of the hundreds of thousands who went on to the streets after the Turkish writer Hrant Dink was shot in 2007 and my deep regret that, despite the work of a foundation established by his widow, the situation in Turkey appears to have got worse not better in the intervening years.

A resolution voted for by MEPs was provoked by dawn police raids on newspapers and television stations in December that led to the arrest of 31 people, mainly journalists, on charges of terrorism – which carry some of the gravest sentences under the Turkish penal code.

Two of the leading journalists arrested openly admit sympathies for the US-based cleric Fethullah Gulen ,whose followers withdrew support from the country’s governing AKP party and whose so-called ‘movement’ does indeed deserve greater scrutiny.

Nevertheless reports suggest no evidence was presented of actual criminal intent against those arrested, with the crackdown fitting a pattern of legal harassment, smears and threats against those who provide political opposition to the government or who critically report on corruption allegations against it.

Our resolution also condemns the recent arrest of a Dutch journalist, demonstrating how foreign journalists are not exempt from attack.

Correspondents of The Economist, Der Spiegel and the New York Times in Turkey have all been threatened, with one CNN correspondent forced to flee the country after being accused of espionage.

Previous attempts to ban social media are also being revived in the country this week, in an apparent attempt to suppress reports Turkey’s intelligence organisation may have been implicated in the supply of arms to ISIS fighters in Syria.

As someone who is proud to call himself a friend of Turkey, and a keen proponent for the country’s accession to the EU, it is with a heavy heart I sign up to such criticisms.

However in negotiations I had to argue against opponents of the country seeking to use this latest incident to introduce wording that would have imposed immediate financial penalties against Turkey or put up new barriers in the membership negotiations.

I did so because politicians as well as journalists must not allow ourselves to be trapped in to self-censorship. On these arrests, it was our duty to speak out.

I am saddened explanations that the release of all but four of the journalists given to me and to my fellow MEPs by the Turkish representative in Strasbourg this week seemed wantonly to ignore the climate of fear and self-censorship which remains inflicted on the country’s press as a result.

It is the blatant denials that undermine trust and confidence with those of us who want to support reform efforts in the country, and which one very senior EU official told me had led to “desperation” in the telephone calls between Brussels and Ankara which followed the arrests.

Meanwhile, former prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, now elected as the country’s president, reacted characteristically by telling a news conference: “Nowhere in Europe or in other countries is there a media that is as free as the press in Turkey.”

The sober truth is that Turkey ranks 154 out of 180 in press freedom according to the Reporters Without Borders index last year.

The annual survey by the Committee to Protect Journalists, published only last month, showed Turkey amongst the top ten countries in the world for imprisoning journalists, ranking alongside Azerbaijan, Iran and China.

However, Erdogan’s protestations must be put in to a context where he also rebuffed European criticisms of the arrests saying the EU should “mind its own business”, and last week when he was prepared to partly attribute the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attack to “Western hypocrisy”.

Today’s European Parliament vote ascribes that hypocrisy instead to the government in Ankara.

I wonder whether the Turkish press will fairly report even this?

This article was posted on 15 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

Rashid Razaq is a reporter for London Evening Standard and a playwright.

What is the solution to the Muslim Problem? Britain has tried multiculturalism; the French, a stricter enforcement of secularism. Neither has been an unequivocal success.

I’m afraid I don’t have the answer. I have only doubts and questions, whereas the terrorists have certainties and guns.

The only thing I can say with a fair amount of confidence is that the right not to be offended is a ridiculous thing. For there is no way to measure a subjective, emotional state other than to ask “Does this offend you?” in the same way you would ask “Are you tired?”, “Are you hungry?”, “Do you love me?”

One person’s silly cartoon is another person’s existential threat. Try as I might, I cannot get offended by a drawing. Maybe I’m a bad Muslim, maybe a true believer would be so mortally wounded by an image, any image, of the Prophet Mohammed that the only remedy is bloodshed. But I don’t think that’s the case. Much of the outrage is manufactured, stoked up by rabble-rousers for political purposes. Because that’s the brilliance of the right not to be offended (Irony — just to be crystal- clear): you can get offended on other people’s behalf, you can get offended about books you haven’t read, about things that may or may not exist.

Loath as I am to bring up scripture in a discussion about religion, the Islamic prohibition against making graven images of the Prophet Mohammed only really applies to Muslims. It stems from the same commandment not to worship false idols, intended to protect against idolatry.

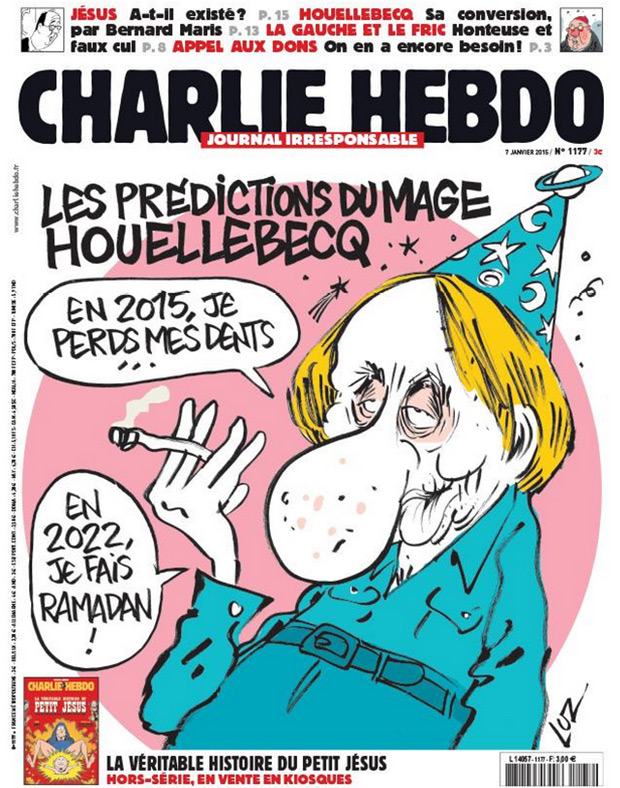

As far as I’m aware neither Stephane Charbonnier nor any of his leading cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo was a practising Muslim. The two victims believed to be Muslims, copy-editor Mustapha Ourad and policeman Ahmed Merabet, appear to have been collateral damage rather than targets.

So, just to make the murders even more pointless, you have Muslims killing non-Muslims for not sufficiently respecting something which they don’t believe in. Irony? I’m not sure.

Not that there is any justification. It is a shabby excuse for a heinous act, convenient religious cover for something that is probably nothing more than a twisted marketing stunt for al Qaeda in Yemen, if initial accounts prove to be true. The killings were not carried out to “avenge” the Prophet’s honour. Their real intent was to remind the West: “We’re still here”.

Many lofty and true words will be written about the need to protect the freedom of expression. But the attack on Charlie Hebdo wasn’t an attack on freedom of expression. It was an attack on an easy target. A group of middle-aged, unarmed cartoonists were never going to be much of a match for battle-hardened jihadists brandishing Kalashnikovs.

Satire is scary for people who can’t live with doubt. Because satire is all about creating doubt, questioning the way things are done, challenging those in power, pushing for change. I don’t know if the killings say more about the power of satire or the weakness of the gunmen’s supposed faith.

The jihadists want us to accept their narrative, that they are brave holy warriors and not just some over-sensitive, bloodthirsty bullies. But I have my doubts. I think the terrorists continue to provoke fear because they’re afraid. Afraid that we’ll realise their brand of religion is a joke.

The arrest of French comedian Dieudonné today appears to be connected to a Facebook comment he posted after Sunday’s march in Paris in which he said he felt he “finally returned home… I feel like Charlie Coulibaly” – remarks that have been interpreted as condoning the action of one of the terrorists involved in the killings of 17 people in Paris last week.

It is important to be clear that while incitement to terrorism is a crime, commentary or jokes about terrorism – no matter how offensive or tasteless – are not. Opinions are protected by the right to freedom of expression.

“You cannot address bigoted and offensive ideas by banning them. To do so simply drives them underground,” said Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg. “The attacks on Charlie Hebdo should be a spur to every one of us to defend ever more vigorously free speech in all forms – even and especially when it represents opinions we find abhorrent or disagree with – so that all views are represented and can be challenged.”

The full text of the Dieudonne remark, later deleted, is as follows: “After this historic march what do I say…Legendary. Instant magic equal to the Big Bang that created the universe. To a lesser extent (more local) comparable to the coronation of Vercingétorix, I finally returned home. You know that tonight as far as I’m concerned I feel like Charlie Coulibaly”.

As Article 19 points out in a statement today, publicly condoning (faire publiquement l’apologie) acts of terrorism is a crime under Article 421-2-5 of the French Criminal Code.

The offence is punishable with up to five years’ imprisonment, and a fine of €75,000. Harsher penalties for the offence are available when it is committed online, allowing up to seven years’ imprisonment and a fine of €100,000.

“International standards are clear that terrorism offences should not be so broad or vague as to encompass expression where there is no actual intent to encourage or incite terrorist acts,” Article 19 said. “To impose criminal sanctions, there must be a direct and immediate connection between the expression at issue, and the likelihood or occurrence of such violence.”