Attacks on journalists and activists must stop

The International Day to End Impunity is a campaign to highlight the necessity of protecting press freedom around the world, says Padraig Reidy (more…)

The International Day to End Impunity is a campaign to highlight the necessity of protecting press freedom around the world, says Padraig Reidy (more…)

On Sunday, the world prepared for President Obama’s first-time visit to the summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). But underneath the press torrent was a lesser-known event: the leaders of the 10 member states of the regional bloc signed the much-lamented ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (AHRD). Freedom of expression, internet privacy, and minority rights are all potential casualties of this document, which amounts to an assortment of titular but pleasant-sounding logorrhea — designed largely by dictators in a region where free expression is, in most countries, on the decline.

The first conundrum? In declaring its broader principles, the charter annuls itself when it states that human rights should be respected everywhere, except that they shouldn’t:

All human rights are universal, indivisible, interdependent and interrelated. All human rights and fundamental freedoms in this Declaration must be treated in a fair and equal manner, on the same footing and with the same emphasis. At the same time, the realisation of human rights must be considered in the regional and national context bearing in mind different political, economic, legal, social, cultural, historical and religious backgrounds.

That’s a huge exception that governments can play with. The US State Department called out concerns of ASEAN’s cultural relativist approach to human rights, a term that labels individual liberties as culturally alien to Asians. It’s a common justification used to curtail expression, made famous when former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore argued at the end of the Cold War that liberal democracy was a Western value that should not be brought to certain countries.

The declaration also employs the obfuscating language of “national security,” “public order” and “public morality” as prerequisites to exercising basic freedoms. Narrowing that framework down to free speech, the declaration reads, for instance: “Every person has the right to be free from … attacks upon that person’s honour and reputation.” Though not legally binding, those phrases lend legitimacy to the wording that Cambodia, Vietnam, and Thailand typically use when jailing critics.

Mam Sonando, director of Cambodia’s independent Beehive Radio station, who was jailed for 20 years in October

“They can say that we banned such-and-such speech because it goes against our national context, or contravenes a vaguely defined notion such as ‘public morality’ or the ‘general welfare of the peoples in a democratic society’,” said Phil Robertson, deputy director of the Asia Division at Human Rights Watch, “or because those making the speech have their rights balanced by duties to the state to not do such a thing.”

In a region where online surveillance is, in most member states, on the rise, internet privacy gets no mention. The Cambodian Center for Human Rights also pointed out that indigenous and LGBT groups appear to have been left out of specific protections from discrimination and the principle of equality. In Southeast Asia, minorities such as the Rohingya, Wa and Shan in Myanmar, the Papuans in Indonesia, and the potpourri of highland groups often called “Montagnards” in Vietnam have all been persecuted in military and police campaigns, and denied cultural rights.

The triumph of local laws over international concepts of rights should not be surprising from a bloc that is sclerotic and, in the past, has been characterised as a “club of dictators.” ASEAN’s background shows why it straddles this non-interference line on its sovereigns: The organisation was born in 1967 out of the devastation of the Vietnam War, when five countries in Southeast Asia were hoping to tether in an anti-communist grouping that could stand on its own against the involvement of the US, the Soviet Union and China.

But its espousal of “territorial integrity” — of respecting a government’s right to rule without the Cold War-style interference from external powers — quickly became an excuse to back dictators in alliances of convenience. In the late 1970s, ASEAN supported the murderous Khmer Rouge forces at the Thai-Cambodia border, which had already overseen the deaths of 1.7 million people in Cambodia. They hoped the rag-tag army could be a buffer to prevent the powerful Vietnamese military from marching across Thailand — a fear that, in hindsight, was probably not justified, even though Vietnam had invaded Cambodia in 1978.

After the Cold War ended, the group switched its focus from security to trade and expanded its membership to include Cambodia, Burma, Brunei, and nominally communist Vietnam and Laos. But political openness has not accompanied economic growth in Southeast Asia. Rather, the group’s foundational peg of “non-interference” remains unchanged despite signing the 2008 ASEAN Charter, and its delegates continue to defer to national governments on questions of free expression.

With that said, does the human rights declaration even matter on free speech issues? Probably not, given the bloc’s chimera of consensus that, put bluntly, is indifference.

Free speech will come from inside the ASEAN member states themselves, rather than from the bureaucrats who exchange flowers, link their hands together in photo ops and call each other “Your Excellency” at summits.

Geoffrey Cain is an editor at New Mandala, the Southeast Asia blog at the Australian National University

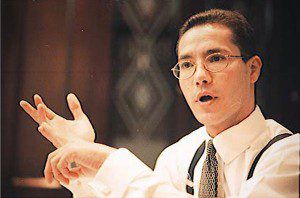

LONDON (INDEX). Exposing financial crime is a dangerous career path. David Marchant — an investigative journalist and publisher of OffshoreAlert — knows that. He has been sued numerous times and has never lost, his first accuser is currently serving 17 years in prison for tax evasion and money laundering.

Offshore alerts specialises in reporting about offshore financial centres (known as OFCs), with an emphasis on fraud investigations, and also holds an annual conference on OFCs focusing on financial products and services, tax, money laundering, fraud, asset recovery and investigations. It caters to financial services providers and other financial institutions.

Marchant talks to INDEX — ahead of the OffshoreAlert Conference Europe: Investigations & Intelligence, 26 – 27 November — about the importance of free expression and the peculiarities of his trade.

INDEX: As investors continue to pour millions of pounds each month into offshore bank accounts, the Western world is in economic disarray, demanding much more from law-abiding taxpayers to bailout banks. What is your view on the economic crisis, and has it had any effect on the type of investigative journalism you practice?

INDEX: As investors continue to pour millions of pounds each month into offshore bank accounts, the Western world is in economic disarray, demanding much more from law-abiding taxpayers to bailout banks. What is your view on the economic crisis, and has it had any effect on the type of investigative journalism you practice?

DAVID MARCHANT: It is unfair to blame the global economic crisis on offshore financial centres. It is, essentially, a people-problem, the majority of whom live in the world’s major countries.

For me, the most interesting aspect of the crisis is that it confirmed what I already knew, i.e. many of the world’s major banks and financial services firms are not well managed. A significant part of the problem is that offering huge short-term financial incentives invites your personnel to act in a manner that is not in the long-term interests of a company. It encourages risk-taking and the concealment of losses to create the appearance of success, as opposed to actual success. It seems that few, if any, material changes have been made to the system, that you can’t change human nature overnight and that history is destined to repeat itself in the future. Other than the crisis causing more schemes to collapse early and there being more to write about, it has had no effect on OffshoreAlert’s investigative reporting.

INDEX: Greek investigative journalist Kostas Vaxevanis was arrested a few days ago in Athens for publishing the “Lagarde List” —containing the names of more than 2,000 people who hold accounts with HSBC in Switzerland (one imagines, hoping to escape the taxman). The list remained unused for two years after Christine Lagarde passed it onto then Finance Minister Giorgos Papakonstantinou. What do you think about it?

DM: It would not surprise me if the Greek authorities had indeed sat on this information. Governments and corruption or incompetence go hand in hand.

INDEX: Tax evasion is not considered money laundering in some jurisdictions, and it looks less frightening than laundering drug or criminal proceeds. Do you hold any views on this subject?

DM: Money laundering is a criminal offence in its own right. The predicate crimes vary country by country and, in some countries, tax evasion is not among them or was not among them now at one time. In the Cayman Islands, for example, fiscal offences were initially omitted from the jurisdiction’s money laundering laws but the jurisdiction was forced — screaming and kicking — into adding them at a later date. Tax evasion clearly should be a predicate crime. Paying taxes is a price we must pay to live in a civilised society. Who wants to live in an uncivilised society? Certainly not me.

INDEX: How do you balance the need for privacy with the need for transparency in the offshore world?

DM: As a journalist, the more transparency the better but information must be handled responsibly. The word “privacy” is a soft word for secrecy and people have secrets for a reason, i.e. they are typically trying to conceal something that is illegal, immoral or otherwise shameful.

INDEX: You receive sponsorship from security companies like Kroll Advisory Solutions. The global intelligence industry caters for crooks and corrupt, repressive governments alongside corporate clients. Twenty years ago, the value of this sector was negligible — today it is estimated to be worth around $3bn. Any thoughts on this?

DM: To be clear, OffshoreAlert is an independent organisation, not beholden to anyone or anything other than accuracy and fairness. We have limited advertising on our web-site but we do have sponsors for our financial due diligence conferences, which is a commercial necessity. The global intelligence industry is like any other. Companies aren’t particularly choosy about who they will accept as clients. It’s all about making money. I have no idea whether the global intelligence industry has become more prevalent or not over the last 20 years. If it has grown significantly, however, I would guess that much of such growth would be fuelled by banks and other financial firms having to comply with tougher anti-money laundering laws.

INDEX: How do you compare your work with that of, for example, Wikileaks?

DM: I have little or no respect for WikiLeaks. In my limited dealings with the organisation, I have found Wikileaks to be amateurish and fundamentally dishonest. In its very early days, it was clear to me that, in one action at federal court in the United States, Wikileaks clearly misled the court. It is not trustworthy. I consider Julian Assange to be an irresponsible, hypocritical, over-hyped poseur. His major talent seems to be self-publicity. I cringe when I see him described as a journalist. It denigrates the entire profession. Fortunately, there are few, if any, similarities between Wikileaks and OffshoreAlert. We’re not in the same business or market and there is a gulf of difference in the level of professionalism between the two.

INDEX: You actually own 100 per cent of OffshoreAlert and I understand that you are not insured against libel and other legal risks in order to avoid “lawyering” your exposes. Is this correct? Is it necessary in order to safeguard your journalistic independence?

Former accountant and self-styled “offshore asset protection guru”,Marc Harris was convicted of money laundering and tax evasion by the US in 2004

DM: I do indeed beneficially own OffshoreAlert in its entirety. Prior to launch in 1997, I looked into purchasing libel insurance. The premiums were reasonable but the problem was that every article would need to be pre-approved by a recognised libel attorney. That would have been costly and would have inevitably led to the attorney recommending that stories be watered down, which would have defeated the primary purpose of OffshoreAlert, which is to expose serious financial crime while it is in progress. I have an even better de facto insurance policy: If someone sues me for libel, I will take all of my incriminating evidence to law enforcement, and do everything in my power to ensure that the plaintiff is held criminally accountable for their actions. This is no idle promise. The first person to sue me for libel (self-proclaimed “King of the Offshore World” Marc Harris) thought he could put me out of business. Instead, he is currently serving 17 years in prison for fraud and money laundering.

INDEX: However, you have been taken to court for libel on many occasions and always won. So the objective behind these law suits seems to be to intimidate or drain you dry. How do you about surviving suing threats?

DM: OffshoreAlert has been sued for libel multiple times in different countries and jurisdictions. [He was sued in the USA (state and federal court), Cayman Islands, Canada (Toronto), Grenada (by then Prime Minister Keith Mitchell), and Panama]. We’ve never lost a libel action, never published a correction or apology to any plaintiffs and never paid — or been required to pay — them one cent in costs or damages. It is a record of which I am very proud. I know how the game is played, I am extremely resourceful, and I am not intimidated easily. This might come across as conceited, but my attitude towards plaintiffs is that I am brighter, tougher and more talented than you and your attorneys and that, if you want to sue me, I will do everything in my power to ensure that you pay the ultimate price of being criminally prosecuted for your actions.

INDEX: According to organisations such as ours, English libel law has been shown to have a chilling effect on free speech around the world. Especially worrying is “libel tourism”, where foreign claimants have brought libel actions to the English courts against defendants who are neither British nor resident in this country. What do you think about it?

DM: British libel law, generally, is among the most repulsive pieces of legislation that exists in the civilised world. It is a reprobate’s best friend and protects the reputations of people who don’t deserve to have their reputations protected. I couldn’t operate OffshoreAlert in the UK or in any country or jurisdiction that has adopted similar laws because OffshoreAlert would be sued out of existence. British libel law is considered to be so repugnant that, in 2010, the United States passed The SPEECH Act that renders British libel judgments unenforceable in the US there is no de facto free speech in Britain because of its libel laws. I find the entire British legal system to be terrible in dispensing justice. In that regard, it is light years behind the legal system that exists in the US, where OffshoreAlert is based.

Miren Gutierrez is Editorial Director of Index

The South African Communist Party (SACP) this week made a public call for a law to be instituted to protect the country’s president against “insults”. The call, by one of its provincial branches, was in response to growing public outrage about R240 million (about £17m) worth of taxpayer’s money spent on upgrading the private homestead of the incumbent, Jacob Zuma.

Minister for higher education and SACP general secretary Dr Blade Nzimande reportedly supported the call by the KwaZulu Natal SACP but later said he is calling for a public debate on the issue.

Two investigations are underway into the price tag attached to “security upgrades” at Zuma’s private residence in Nkandla in rural KwaZulu Natal, which far exceeds that of residences of former presidents.

South Africa’s President Jacob Zuma speaking to a union congress (Demotix)

In parliament last week (15 Nov) Zuma insisted that “all the buildings and every room we use in that residence was [sic] built by ourselves.” In response, Lindiwe Mazibuko, the leader of the official opposition Democratic Alliance (DA), pointed out that the upgrades are not limited to “security” but include 31 new buildings, lifts to an underground bunker, air conditioning systems, a visitors’ centre, gymnasium and guest rooms. It reportedly even includes “his and hers bathrooms”.

Since the excessive amount became known at a parliamentary meeting in May this year, investigative journalists have requested further information using the Protection of Access to Information Act. The public works department, however, refused to comply, citing the National Key Points Act, which makes it illegal to distribute information about sites related to national security. The public works ministry also launched an investigation to find the whistleblower who leaked the information to the media, with a view to prosecution.

The SACP believes that questions about the Nkandla extensions, including by DA leader Helen Zille who led a thwarted visit to the homestead, harm Zuma’s dignity. In a thinly veiled threat, the SACP claimed such questions would undermine South Africa’s “carefully constructed and negotiated reconciliation process and could unfortunately plunge our country into an abyss of racial divisions and tensions.”

Insult laws “protecting” presidents from criticism exist in France, Spain and across South America and Africa.

Christi van der Westhuizen is Index on Censorship’s new South African correspondent