6 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News

In France, Bob Dylan is being officially investigated for “incitement to hatred” against Croats for comparing their relationship to Serbs with that between Nazis and Jews in an interview.

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression.

Freedom of information

Freedom of information is an important aspect of the right to freedom of expression. Without the ability to access information held by states, individuals cannot make informed democratic choices. Many EU member states have failed to adequately protect freedom of information and the Commission has been criticised for its failure to adequately promote transparency and uphold its commitment to freedom of information.

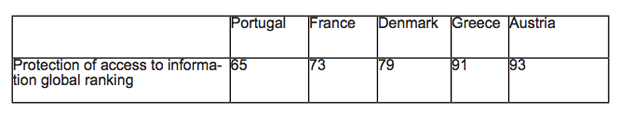

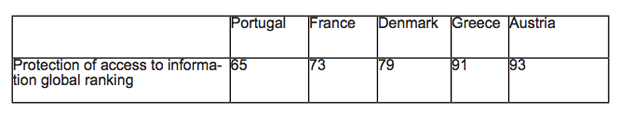

When it comes to assessing global protection for access to information, not one European Union member state ranks in the list of the top 10 countries, while increasingly influential democracies such as India do. Two member states, Cyprus and Spain, are still without any freedom of information laws. Of those that do, many are weak by international standards (see table below).

In many states, the law is not enforced properly. In Italy, public bodies fail to respond to 73% of requests.

The Council of Europe has also developed a Convention on Access to Official Documents, the first internationally binding legal instrument to recognise the right to access the official documents of public authorities. Only seven EU member states have signed up the convention.

Since the Lisbon Treaty came into force, both member states and EU institutions are both bound by freedom of information commitments. Article 42 (the right of access to documents) of the European Charter of Fundamental Rights now recognises the right to freedom of information for EU documents as a fundamental human right Further, specific rights falling within the scope of freedom of information are also enshrined in Article 41 of the Charter (the right to good administration).

As a result, the European Commission has embedded limited access to information in its internal protocols. Yet, while the European Parliament has reaffirmed its commitment to give EU citizens more access to official EU documents, it is still the case that not all EU institutions, offices, bodies and agencies are acting on their freedom of information commitments. The Danish government used their EU presidency in the first half of 2012 to attempt to forge an agreement between the European Commission, the Parliament and member states to open up public access to EU documents. This attempt failed after a hostile response from the Commission. Attempts by the Cypriot and Irish presidencies to unblock the matter in the Council also failed.

This lack of transparency can and has impacted on public’s knowledge of how decisions that affect human rights have been made. The European Ombudsman, P. Nikiforos Diamandouros, has criticised the European Commission for denying access to documents concerning its view of the United Kingdom’s decision to opt out from the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. In 2013, Sophie in’t Veld MEP was barred from obtaining diplomatic documents relating to the Commission’s position on the proposed Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA).

Hate speech

Across the European Union, hate speech laws, and in particular their interpretation, vary with regard to how they impact on the protection for freedom of expression. In some countries, notably Poland and France, hate speech laws do not allow enough protection for free expression. The Council of the European Union has taken action on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by promoting use of the criminal law within nation states in its 2008 Framework Decision. Yet, the Framework Decision failed to adequately protect freedom of expression in particular on controversial historical debate.

Throughout European history, hate speech has been highly problematic, from the experience and ramifications of the Holocaust through to the direct incitement of ethnic violence via the state run media during wars in the former Yugoslavia. However, it is vital that hate speech laws are proportionate in order to protect freedom of expression.

On the whole, the framework for the regulation of hate speech is left to the national laws of EU member states, although all member states must comply with Articles 14 and 17 of the ECHR.[1] A number of EU member states have hate speech laws that fail to protect freedom of expression –- in particular in Poland, Germany, France and Italy.

Article 256 and 257 of the Polish Criminal Code criminalise individuals who intentionally offend religious feelings. The law criminalises public expression that insults a person or a group on account of national, ethnic, racial, or religious affiliation or the lack of a religious affiliation. Article 54 of the Polish Constitution protects freedom of speech but Article 13 prohibits any programmes or activities that promote racial or national hatred. Television is restricted by the Broadcasting Act, which states that programmes or other broadcasts must “respect the religious beliefs of the public and respect especially the Christian system of values”. In 2010, two singers, Doda and Adam Darski, where charged with violating the criminal code for their public criticism of Christianity.[2] France prohibits hate speech and insult, which are deemed to be both “public and private”, through its penal code[3] and through its press laws[4]. This criminalises speech that may have caused no significant harm whatsoever to society, which is disproportionate. Singer Bob Dylan faces the possibility of prosecution for hate speech in France. The prosecutor’s office in Paris confirmed that Dylan has been placed under formal investigation by Paris’s Main Court for “public injury” and “incitement to hatred” after he compared the relationship between Croats and Serbs to that of Nazis and Jews.

The inclusion of incitement to hatred on the grounds of sexual orientation into hate speech laws is a fairly recent development. The United Kingdom’s hate speech laws contain specific provisions to protect freedom of expression[5] but these provisions are not absolute. In a landmark case in 2012, three men were convicted after distributing leaflets in Derby depicting a mannequin in a hangman’s noose and calling for the death sentence for homosexuality. The European Court of Human Rights ruled on this issue in its landmark judgment Vejdeland v. Sweden, which upheld the decision reached by the Swedish Supreme Court to convict four individuals for homophobic speech after they distributed homophobic leaflets in the lockers of pupils at a secondary school. The applicants claimed that the Swedish Supreme Court’s decision to convict them constituted an illegitimate interference with their freedom of expression. The ECtHR found no violation of Article 10, noting even if there was, the interference served a legitimate aim, namely “the protection of the reputation and rights of others”.

The widespread criminalisation of genocide denial is a particularly European legal provision. Ten EU member states criminalise either Holocaust denial, or the denial of crimes committed by the Nazi and/or Communist regimes. At EU level, Germany pushed for the criminalisation of Holocaust denial, culminating in its inclusion from the 2008 EU Framework Decision on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by means of criminal law. Full implementation of the Framework Decision was blocked by Britain, Sweden and Denmark, who were rightly concerned that the criminalisation of Holocaust denial would impede historical inquiry, artistic expression and public debate.

Beyond the 2008 EU Framework Decision, the EU has taken specific action to deal with hate speech in the Audiovisual Media Service Directive. Article 6 of the Directive states the authorities in each member state “must ensure by appropriate means that audiovisual media services provided by media service providers under their jurisdiction do not contain any incitement to hatred based on race, sex, religion or nationality”.

Hate speech legislation, particularly at European Union level, and the way this legislation is interpreted, must take into account freedom of expression in order to avoid disproportionate criminalisation of unpopular or offensive viewpoints or impede the study and debate of matters of historical importance.

[1] ‘Article 14 – discrimination’ contains a prohibition of discrimination; ‘Article 17 – abuse of rights’ outlines that the rights guaranteed by the Convention cannot be used to abolish or limit rights guaranteed by the Convention.

[2] The police charged vocalist and guitarist Adam Darski of Polish death metal band Behemoth with violating the Criminal Code for a performance in 2007 in Gdynia during which Darski allegedly called the Catholic Church “the most murderous cult on the planet” and tore up a copy of the Bible; singer Doda, whose real name is Dorota Rabczewska, was charged with violating the Criminal Code for saying in 2009 that the Bible was “unbelievable” and written by people “drunk on wine and smoking some kind of herbs”.

[3] Article R625-7

[4] Article 24, Law on Press Freedom of 29 July 1881

[5] The Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006 amended the Public Order Act 1986 by adding Part 3A[12] to criminalising attempting to “stir up religious hatred.” A further provision to protect freedom of expression (Section 29J) was added: “Nothing in this Part shall be read or given effect in a way which prohibits or restricts discussion, criticism or expressions of antipathy, dislike, ridicule, insult or abuse of particular religions or the beliefs or practices of their adherents, or of any other belief system or the beliefs or practices of its adherents, or proselytising or urging adherents of a different religion or belief system to cease practising their religion or belief system.”

21 Nov 2012 | Africa, South Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa

South Africa’s Right2Know Campaign (R2K) is “Camping out for Openness” outside parliament in Cape Town this week as deliberations over the draconian Protection of State Information Bill draw to a close.

The National Council of Provinces, the second house of parliament, is due to adopt the bill by the end of November. The bill is ostensibly aimed at instituting a long-overdue system to regulate access to government documents.

However, despite persistent appeals from, among others, luminaries such as Nobel Laureate Nadine Gordimer, the Secrecy Bill’s system of classification and declassification has not been couched in the country’s constitutional commitment to an open democracy and the free flow of information.

Instead it opens the door to the over-classification of state information while instituting harsh punishments for the possession of classified information, undermining basic citizenship rights.

Pressure from civil society, led by the R2K Campaign, produced limited concessions this year. One of the most pertinent demands was to include a public interest defence clause to ameliorate the anti-democratic effects of the bill. The ruling African National Congress (ANC) eventually conceded by allowing a clause enabling a public interest defence, but only if the disclosure revealed criminal activity. This has been criticised as an unreasonably high threshold.

Right2Know march in Pretoria, South Africa, September 2012. Jordi Matas | Demotix

The ANC this month backtracked on two other key concessions, as pressure from state security minister Siyabonga Cwele on ANC parliamentarians seemingly paid off:

- The Secrecy Bill at first took precedence over the Promotion of Access of Information Act (PAIA). PAIA allows citizens to request information from government agencies. The ANC then agreed to an amendment that would give PAIA precedence. This decision was again overturned after pressure from Cwele. Activists argue that allowing the Secrecy Bill to trump PAIA is unconstitutional, as PAIA is prescribed by the constitution and has to remain the supreme law in access to information matters.

- A five-year sentence for disclosing classified information has been reintroduced after the ANC agreed to have it removed. This will actively discourage whistleblowers in the civil service from coming forward with information revealing corruption.

Cwele’s predecessor, Ronnie Kasrils, this week addressed the R2K camp outside parliament, distancing himself from what he deemed the “devious” and “toxic” bill. While he was minister, he withdrew the 2008 version of the bill after a similar outcry about its lack of constitutionality.

According to R2K, the other remaining problems with the Secrecy Bill include:

- It criminalises citizens instead of holding to account civil servants who are responsible for keeping secrets.

- A whistleblower, journalist or activist disclosing classified information with the purpose of revealing corruption or other criminal activity can still be prosecuted under the “espionage” and related offences clauses to avoid them invoking the limited public interest defence.

- Persons in possession of classified state information face draconian jail terms of up to 25 years.

- The bill’s procedure to apply for the declassification of information conflicts with PAIA, while the newly created Classification Review Panel is not sufficiently independent: “The simple possession of classified information appears to be illegal even pending a request for declassification and access.”

- Someone can be prosecuted for “espionage”, “receiving state information unlawfully” (to benefit a foreign state), and “hostile activity” even without proof that the accused intended to benefit a foreign state or hostile group or prejudice national security — only that the accused knew this would be a “direct or indirect” result.

- Information classified under apartheid law and policies that may be counter to the constitution remain classified, pending a review for which no time limit is set.

Parliament’s engagement with the bill, which started in July 2010, has been characterised by Orwellian “doublethink”, as exemplified in Cwele’s declaration that “protect(ing) sensitive information … is the oil that lubricates our democracy and we have no intention — not today, not ever — to undermine the freedom we struggled and sacrificed for all these years”.

R2K has vowed to continue pressuring parliamentarians to replace the Secrecy Bill with a law “that genuinely reflects a just balance between the public’s right to know and [the] government’s need to protect limited state information”.

Christi van der Westhuizen is Index on Censorship’s new South Africa correspondent

More on this story:

28 Feb 2012 | Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa

Over 70 per cent of East Africa’s population lives in rural communities: despite the proliferation of radio stations, weekly and daily newspapers, and television stations, in Tanzania alone there are 17 radio stations, 61 national papers and 11 state and private TV stations. In Kenya and Uganda there are even more media outlets but despite this, and even though ‘freedom of information’ is being enshrined in constitutions (in Kenya and Tanzania), there are major challenges to free speech and accessing information.

Mwalimu Asya Mgongo is one of three teachers on the island of Chole Mjini, total population 950 people. Like many East Africans lucky enough to have a job, her monthly 120,000 TZ shillings (£45) teacher’s salary supports eight family members. She is listening to her phone as she sits on ‘the harbour’: a small slab of concrete overlooking the Indian Ocean, her headscarf covering her head — this is a 100 per cent Muslim island. “For me getting the information to teach my children really is a problem — Dar Es Salaam is over 12 hours away by boat, local bus and another bus. Books! You’re joking! They’re gold here. The government gives us text books, but there’s no postal system, and the even the newspapers arrive a day late, if they arrive, so there’s little point. I do have a radio, I listen to the BBC World Service and the German one, and I try and tell as many people as possible”. She looks out to sea a bit dreamily: “Internet, being able to get BBC news daily on the internet, I would love that.”

Her sentiments are echoed by Mama Dayema and Mama Mahogo, both cooks at the local Chole Mjini eco-lodge on the island, which, over the 20 years of its existence, has single-handedly raised the levels of education on the island by building a primary school and funding up to eleven people to go to university — a first for the island. Mama Dayema is clear about what information is missing from their lives: “We tend to rely on taxi drivers (on the sister Mafia island, a ten minute boat ride away) for information on staples like maize, rice, cooking oil. We’d really like to be able to chat to the guests in English. I am the only villager on the island with solar power, which I found out about through information from foreigners. The key is education, completely: my children need to get ahead and know how the world is, even if I don’t. We are cut off, ignored actually, by mainland government, and policies, but in some ways I don’t mind. We have abundant fruits — oranges, mangoes, and real trust here, we look after each other. On the mainland (Tanzania) there’s thieves, diseases, adulterers, bad people.”

Salma Meremeta left Mafia, for work in the capital; “Honestly we are isolated and abandoned here, the government doesn’t care about us one bit — when I come home I am shocked by the lack of information here, it’s bad.”

Certainly for tourists the island is as close to paradise as it gets, and the isolation a “feature” of the attraction. However, it’s a recognised problem that rural people, particularly women, are marginalised from the creation, circulation and consumption of information. Ironically rural people are often far more critical, and vociferous about political policy issues (water and the price of basics) because they are living so close to the breadline. Yet media houses and reporters are based in capitals like Kampala and Nairobi, and infrastructure — lack of good roads and the expense of flying — makes distribution of newspapers extremely expensive (thus impossible). It is rare for reporters to get the resources, support and incentives to report on “rural” issues.

On Chole Mjini island (which is 250km south of Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, 1.5 square km wide, in the middle of the Indian ocean) the main public space in the village is dominated by a television hooked up to one of the two electricity points on the island. Football results and news are the popular crowd-pleasers. Up to two hundred men at a time pay 200 TZ shillings (ten pence) to watch for the evening; for 100 TZ shillings they can also charge their phones. As Saidi, says “It’s not really ok for women to be in public watching television. But we are an oral culture, so for example things like health messages (recently the US government donated mosquito nets to the island) don’t get spread on tv on radio, but by word of mouth. Or by the Imam at the call to prayer. We’re extremely forgiving and compassionate here, as a Muslim culture, so our sick people, we have two HIV victims, they are looked after by us, they are not ostracised. If we feel our sheha’s (Chiefs) are being unreasonable or unfair, we ignore them, or get rid of them. The island is so small there’s a sort of democracy. Go to the mainland? Me! No, never, I love it here”.

Figures for east African internet useage are not entirely accurate, but according to survey group Afrobarometer Tanzania scores the lowest, with just one per cent of the population having access to internet, . On Chole Mjini no-one has a computer, thus there is no internet access. Mama Dayema’s daughter, Mwana, is a striking, educated 24 year old with her mobile phone neatly wrapped in a flannel and tucked into her bra. She is ambivalent “Yes, I suppose part of me is interested in the fact that slavery was only abolished here in 1922, or the Shirazi Persians built palaces here in the past, but honestly I am more interested in modern things, like music and fashion from Dar Es Salaam, or football results, not history.”

One of the downsides of lack of information is the prevalence of gossip. People pick up snippets of news, but it gets mangled through the rumour mill. It’s telling that despite the lack of media in Swahili there is no concrete way to say “I am bored”.