Gay rights in Lebanon: The good, the bad and the ugly

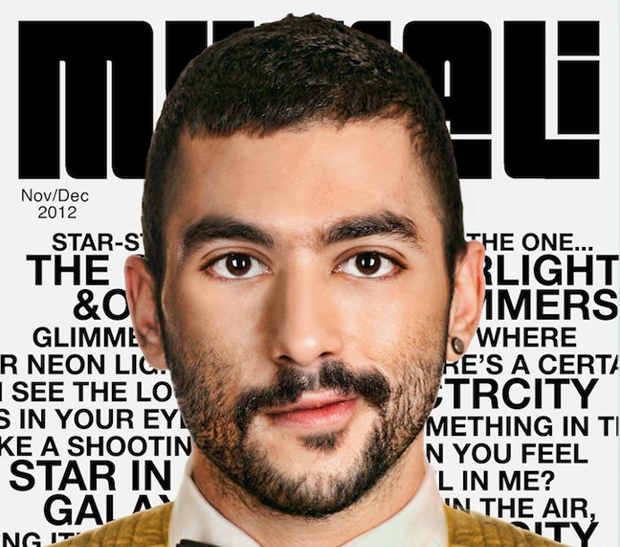

Hamed Sinno, who is openly gay, is the lead singer of Mashrou’ Leila

While walking the streets of the upscale downtown district of Beirut, or sipping cocktails in one of El-Hamra’s bustling bars, one could easily forget that Lebanon is a country where civil liberties are still in debate.

Article 534 of the Lebanese penal code states: “Any sexual intercourse contrary to the order of nature is punished by imprisonment for up to one year.” The vaguely worded article has and is still being used to crackdown on the LGBT community in Lebanon. Compared to its neighbours in the Middle East, Lebanon has long been considered one of the least conservative countries in the region. According to a poll conducted by the Pew Research Centre in 2013, 18% of the Lebanese population thinks that homosexuality should be accepted in the society, putting it way ahead of Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia where almost 97% of the population views homosexuality as deviant and unnatural.

The Lebanese Psychiatric Society issued a statement in early 2013 saying that: “The assumption that homosexuality is a result of disturbances in the family dynamic or unbalanced psychological development is based on wrong information” — making Lebanon the first Arab country to dismiss the belief that homosexuality is a mental disorder. On 28 January 2014, Judge Naji El Dahdah of Jdeideh Court in Beirut dismissed a claim against a transgender woman accused of having a same-sex relationship with a man, stating that a person’s gender should not simply be based on their personal status registry document, but also on their outward physical appearance and self-perception. The ruling relied on a 2009 landmark decision by Judge Mounir Suleimanfrom the Batroun Court that consenual relations can not be deemed unnatural. “Man is part of nature and is one of its elements, so it cannot be said that any one of his practices or any one of his behaviours goes against nature, even if it is criminal behaviour, because it is nature’s ruling,” stated Suleiman.

Despite the recent positives, being gay in Lebanon is still a taboo. In a country drenched in sectarianism, debates about homosexuality are easily dismissed in the name of religion and homosexuals are accused of promoting debauchery.

“People in Lebanon, and across the region, still act like homosexuality doesn’t exist in our society,” said Kareem, who requested that Index only use his first name. “I think it’s important that we start the conversation and get the issues out in the open, so people can start acknowledging it and then decide their stance on. The fight for our rights comes later on,” he added.

In 2013, Antoine Chakhtoura, mayor of the Beirut suburb of Dekwaneh, ordered security forces to raid and shut-down Ghost, a gay-friendly nightclub. “We fought battles and defended our land and honor, not to have people come here and engage in such practices in my municipality,” the mayor asserted.

Four people were arrested during the raid and brought back to municipal headquarters where they were subject to both physical and verbal harassment: forced to undress, enact intimate acts which included kissing, as well as being violently beaten. Marwan Cherbel, minister of interior at the time of the incident, backed the mayor’s actions, adding that: “Lebanon is opposed to homosexuality, and according to Lebanese law it is a criminal offence.”

Unfortunately, this was not an isolated incident. In a similar raid on a movie theatre in the municipality of Burj Hammoud known to cater for a gay clientele, 36 men were arrested and forced to undergo the now abolished anal probes — known as tests of shame. The raid came only a few months after Lebanese TV host Joe Maalouf dedicated an episode of his show Enta Horr (You’re Free) to exposing a porn cinema in Tripoli where it was claimed that young boys were being sexually abused by older men.

“The fact that these incidents received a lot of media coverage, some of which denounced the raids, is a sign that the public is little by little taking an interest in the issue of gay rights,” said Kareem. “Five or six years ago, this could have easily gone unnoticed. While the gay community might not be fully accepted or tolerated in Lebanon, it has been gaining a lot more visibility in recent years.”

Helem, a Beirut-based NGO, was established in 2004 to be the first organisation in the Middle East and Arab world to advocate for LGBT rights. In addition to campaigning for the repeal of Article 543, Helem offers a number of services, including legal and medical support to members of the LGBT community. Organisations like Helem and its offshoot Meem, a support group for lesbian women, had a huge impact on raising awareness and correcting misconceptions about homosexuality. Support from Lebanese public figures has also been on the rise in recent years. For example, popular TV host Paula Yacoubian and pop star Elissa have both shown support for the LGBT community in Lebanon via their Twitter accounts.

While the struggle to change the law continues, young artists have been challenging social norms through art. Mashrou’ Leila, a Beirut-based indie rock band, has sparked a lot of controversy thanks to their songs, in which they unapologetically sing about sex, politics, religion and homosexuality in Lebanon. In Shim el Yasmine, the band’s lead singer, Hamed Sinno, who is openly gay, sings about an old love, a man whom he wanted to introduce to his family and be his housewife. Director and art critic, Roy Dib, recently won the Teddy Award for best short film in 2014 at the 64th Berlinale International Film Festival with his film Mondial 2010. The film tells the story of a gay Lebanese couple on the road to a holiday weekend in Ramallah, Palestine. It tries to explore the boundaries that make it impossible for a Lebanese person to go into Palestine, as well as the challenges faced by a homosexual couple in the region.

The battle for gay rights in Lebanon is multilayered, and while change is starting to feel tangible, there is still a lot to be done.

This article was originally posted on 24 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org