Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

American academic Alexa Huang explores how Shakespeare’s plays were edited to make them more acceptable to Victorians.

Shakespeare has been used to divert around censorship, “sanitised” and redacted for children, young adults and school use, and even used as a form of protest all over the world. While censors have reacted differently to Shakespeare (sometimes with a blind eye), self-censorship (by directors and audiences) is part of the picture as well.

Not all censors work in the capacity of a public official. Many censors are in fact editors, writers and educators who are gatekeepers of specific forms of knowledge. Julius Caesar, for example, is often deemed one of the more appropriate plays to teach and perform in American school systems, because the themes of honor, free will and principles of the republic (as opposed to more sexually charged themes in other plays) are considered inspiring and suitable in the educational context.

The themes in such plays as Romeo and Juliet (teen exuberance and sex), The Merchant of Venice (anti-Semitism), Othello (racism and domestic violence), and Taming of the Shrew (sexism) make modern audiences uncomfortable, but they compel us to ask harder questions of our world.

While Shakespeare has been a large part of American cultural life, the “Shakespeare” that is taught and enacted in schools has often been redacted and even censored. But this is not a new phenomenon. The history of bowdlerized Shakespeare goes back to the nineteenth century. To bowdlerize a classic means to expurgate or abridge the narrative by omitting or modifying sections that are considered vulgar.

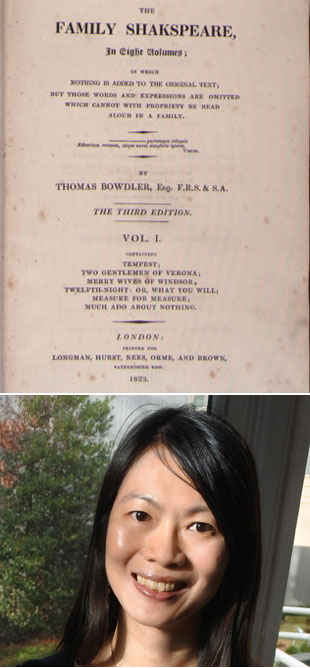

In fact, the term “bowdlerized” comes from Henrietta “Harriet” Bowdler who edited the popular, “family-friendly” anthology The Family Shakespeare (1807) which contains 24 edited plays. The anthology sanitised Shakespeare’s texts and rid them of undesirable elements such as references to Roman Catholicism, sex and more. The anthology was intended for young women readers.

Multiple ambiguities in Shakespeare are replaced by a more definitive interpretation. Ophelia no longer commits suicide in Hamlet. It is an accidental drowning. Lady Macbeth no longer curses “out, damned spot” but instead she says “Out, crimson spot!” Prostitutes are omitted, such as Doll Tearsheet in Henry IV Part 2. The “bawdy hand of the dial” (Mercutio) in Romeo and Juliet is revised as “the hand of the dial.”

Contrary to popular imagination, censorship is not a top-down operation. Instead, it is often a communal phenomenon involving both the censors and the receivers who willingly accept the Shakespeare that has been improved upon. Family Shakespeare was itself a family project. Thomas Bowdler (1754-1825) worked with his sister Henrietta Bowdler to bowdlerize or clean up the classics. The subtitle of the volume states that “nothing is added to the original text; but those words and expressions are omitted which cannot with propriety be read aloud in a family.” Shakespeare is credited as the author, though Bowdler made clear the Bard needed quite some heavy-handed editing.

Ironically, Henrietta Bowdler was herself censored. Thomas Bowdler’s name appears on the cover. It took two centuries for Henrietta to be credited for the anthology, for obviously there is no way she could have admitted that she recognised the bawdy puns in Shakespeare, much less editing them out of Shakespeare. The Bowdlers are among the better-known “censors” in the nineteenth century who editorialised the classics including Shakespeare.

When laying out her editorial principles in the preface, Bowdler does not hesitate to criticise the “bad taste of the age in which [Shakespeare] lived” and Shakespeare’s “unbridled fancy”:

The language is not always faultless. Many words and expressions occur which are of so indecent Nature as to render it highly desirable that they should be erased. But neither the vicious taste of the age nor the most brilliant effusions of wit can afford an excuse for profaneness or obscenity; and if these can be obliterated the transcendent genius of the poet would undoubtedly shine with more unclouded lustre.

She further explains her motive in The Times in 1819, emphasising that the “defects” in Shakespeare have to be corrected:

My great objects in the undertaking are to remove from the writings of Shakespeare some defects which diminish their value, and at the same time to present to the public an edition of his plays which the parent, the guardian and the instructor of youth may place without fear in the hands of his pupils, and from which the pupil may derive instruction as well as pleasure: and without incurring the danger of being hurt with any indelicacy of expression, may learn in the fate of Macbeth, that even a kingdom is dearly purchased, if virtue be the price of acquisition

While censorship carries a negative connotation in our times, The Family Shakespeare did broaden Shakespeare’s audience and readership. While American schools continue to redact Shakespeare, they also infuse Shakespeare into the American cultural life in various forms.

Alexa Huang will be participating in the Index on Censorship magazine panel at the Hay Festival.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91322″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229008534812″][vc_custom_heading text=”Bowdler revisited: Shakespeare

” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229008534812|||”][vc_column_text]March 1990

Artist Jane Zweig discovers books burned in Boston and looks at how Romeo and Juliet has been censored in America.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94784″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227508532458″][vc_custom_heading text=”Censoring Shakespeare” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064227508532458|||”][vc_column_text]September 1975

A Lithuanian stage producer was dismissed from his post after sending an ‘open letter’ to Soviet authorities protesting censorship in theatre.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”93836″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228508533832″][vc_custom_heading text=”Clampdown on drama” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228508533832|||”][vc_column_text]November 2007

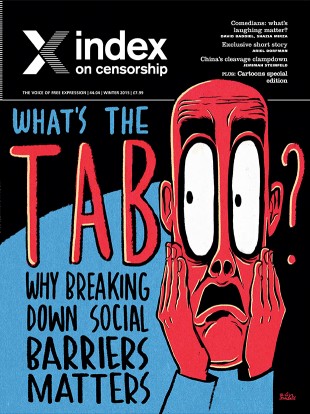

Livingstone Njomo Waidhura reports on drama taught in schools and whether Shakespeare is a suitable hero for Kenya. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The unnamed” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2016 Index on Censorship magazine celebrates the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death, looking at how his plays have been used around the world to sneak past censors or take on the authorities – often without them realising. Our special report explores how different countries use different plays to tackle difficult themes.

With: Jan Fox, György Spiró, Martin Rowson[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”86201″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/02/staging-shakespearean-dissent/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Spring 2016 cover

Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley introduces our Shakespeare special issue, which, as the 400th anniversary of his death approaches, explores how his plays have been used to circumvent censorship and tackle difficult issues around the world, from Bollywood adaptions to Othello in apartheid-era South Africa and a ground-breaking recent performance of Romeo and Juliet between Kosovan and Serbian theatres

Theatre, in whatever form it takes, tells us something about society. Sometimes the stories are uncomfortable, but they need to be explored.

Telling stories that challenge societal realities requires performers to negotiate their way around obstacles. In authoritarian countries performing works of “established” or “historic” playwrights can give actors the chance to tackle significant themes that would otherwise never be allowed.

Poet Robert Frost said writing free verse was like playing tennis with the net down. But where nets are still up, performances of Chekhov, Shakespeare, and Cicero may squeeze over a few shots, where a new and unknown writer’s work would face far more rigorous opposition from the authorities. On the occasion of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, in this issue we take a look at the words of the son of Stratford and why they are still performed around the world.

One of theatre’s challenges is that it must continue to make sense to all audiences, the young, the old and everyone in between. Shakespeare’s plays can be ballsy, straightforward and about the ordinary. This is no doubt why his words have had influence for so long, while other playwrights have been forgotten.

This appeal, and relevance, remains a challenge for writers and directors. After university, I worked for a few months in the legendary Hull Truck theatre in the north-east of England, led by artistic director and playwright John Godber. What Godber did in a working-class city where few people would think, “Hey, let’s go see a play tonight”, was to write and stage plays that sounded like they were about normal people and normal things.

The most famous, Bouncers, is about the people who do door security in nightclubs. A tale of ordinary life, it was funny, and lots of people came to see it in the little theatre in the untarted-up bit of Hull, around the corner from where millions of milk floats loaded up. And people who didn’t normally go to the theatre thought it was alright for them and told their families and their friends it was a laugh, and so more and more of them came to see more Godber plays. I re-read Bouncers a month ago, and I realised (I guess, I had forgotten), it was more than just funny. There’s real stuff in there about how people live and what they dream and how they find a compromise with life, and what needs to change. Hard stuff. Important stuff. Social comment. Hidden in there among the jokes.

That’s how theatre informs us of lives beyond our own. And that’s why, sometimes, governments fear it. And that’s why in another place, and under another type of government, a play like Bouncers might slip its social messages by those hard-line censors who might not think it’s about anything but some fat bald guys who work on the door at a dodgy nightclub having a chat.

But the other role of stories, plays and art is that they also have the power to goad, protest and say stuff that normally can’t be said. Sometimes stories make what had been outrageous or out-of-the-ordinary feel more acceptable. Sometimes fiction can go places where newspapers can’t, but still deal with the real.

Arthur Miller’s 1952 play The Crucible used the Salem Witch Trials to take a poke at the power of accusation and public panic happening in McCarthyite trials, with their accusations of “communism” which left thousands of people blacklisted and unemployed. People from postmen to Hollywood producers were called to give evidence to the House of Un-American Activities Committee, which aimed to “out” those with left wing or pro-Communist views as dangerous. Despite the horrifically charged climate of the “reds under the bed” era, which meant former stars such as Charlie Chaplin and Orson Welles were forced into exile, Miller was still able to get his play produced. It remains a classic, still relevant after all these years.

The similarities between Salem and the McCarthy trials were obvious to those that thought about it. But sometimes those who are appointed as censors are not the thinking types. So ideas slip by them. And that can be useful.

Shakespeare, of course, has plenty of controversy, inspiration and power within his plays. It’s just less obvious to those who aren’t paying attention. There’s nothing mousy and out-of-date about the speech of roaring rhetoric of Henry V to his rag-taggle followers, to raise spirits and to go forth against a much larger army: “We few, we happy few, we band of brothers, for he today that sheds his blood with me shall be my brother.”

Henry V’s speech could still be used to rally the troops. They still feel pointed, and relevant. Yet because Shakespeare is Shakespeare, his words and ideas escape the red pen of the brutal censor more than others do. “Centuries out of date”, the censors and government red-penners must think. “Can’t do any harm.”

So in some countries, Zimbabwe among them, Shakespeare is used to smuggle ideas of protest past those who veto that kind of thing. Playwright Elizabeth Zaza Muchemwa says in her country, where there are so many restrictions on theatre companies, Shakespeare appears to slip through the net, raising storylines of senility of a king (King Lear) and of overthrowing of a leader (Julius Caesar), which feel important to Zimbabwean citizens dealing with the long last days of an elderly ruler. Shakespeare’s writing continues to inspire, she says, in her piece.

But the badge of Shakespeare doesn’t always mean productions will escape the long reach of the law. In 1981, a Turkish production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream came to the stage as a military government stepped up its power. As Index’s Turkey editor Kaya Genç outlines in the magazine any public event, newspaper article, poem or artistic production carrying even the slightest trace of dissent against the military authority was certain to be punished. This production was felt to have highlighted the relationship between the elite and the rest (the rude mechanicals) and how status was used for power. Eight members of the cast ended up shaven-headed in prison in the next few months. The play did not squeeze by. It was noticed.

Leading Turkish theatre director Kemal Aydoğan, who produced the latest version of the play in Turkey, tells Index magazine that the Dream has a strong relevance to troubles in his nation today. He sees a parallel between the struggle between desire and the law, and the dream of the forest, a place where desire and equality dominates.

Don’t miss another gem in the latest magazine, Jan Fox’s long-form essay on the love/hate relationship the USA has, and has had, with Shakespeare (page 12). The Puritan founders felt all theatre was beyond the pale, and looked frowningly on its ribaldry. So this is a nation with a core of censorship at odds with its commitment to its First Amendment freedom of expression. LA-based Fox covers why Shakespeare still upsets parents because of its drama around everything from teenage suicide to under-age sex. “Shakespeare is telling us about our secret self and that’s what people are afraid of,” Gail Kern Paster, editor of the US-based journal Shakespeare Quarterly tells Fox.

While plays by established writers can smuggle through dissent and protest in countries with strict reins of performance exist, as nations move towards greater democracy then the public must expect and demand far more provocative, outrageous and openly challenging material from its theatre as well as welcoming the established gems. We should all look forward to the signs of those times.

Order your full-colour print copy of our Shakespeare magazine special here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Magazines are also on sale in bookshops, including at the BFI and MagCulture in London as well as on Amazon and iTunes. MagCulture will ship to anywhere in the world.

Related:

Award-winning cartoonist discusses his design of the latest Index on Censorship magazine cover

Table of contents

Subscriptions

The winter 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, focusing on taboos. Cover image by Ben Jennings

Join Index on Censorship for a taboo-busting evening at London’s best alternative venue – the Royal Vauxhall Tavern – to celebrate the launch of What’s the Taboo? – Index’s latest magazine featuring stories of the most controversial subjects from around the world.

With a panel that includes comedians Shazia Mirza and Grainne Maguire – we’ll be tackling tricky subjects – nudity, atheism, porn in China, mental health and racism could all be on the cards. If you want to explore and question who makes the rules when it comes to taboos – join us for what will be a dynamic evening exploring the unthinkable, the unmentionable and the unacceptable.

Following the panel event stick around for a special DJ set – Taboo Disco!

When: Wednesday 27 January 6:00pm – 11:00pm (6:00pm: Doors open & drinks; 6:30-8:00pm: What’s the Taboo?; 8:00-11pm: Taboo Disco DJ set)

Where: The Royal Vauxhall Tavern, 372 Kennington Lane, London SE11 5HY (map)

Tickets: Free but limited. Tickets must be booked in advance by emailing: [email protected]

More on the speakers:

Shazia Mirza is an award-winning comedian and columnist. TV Appearances include: Have I Got News For You, F*** Off, I’m a Hairy Woman, NBC’s Last Comic Standing and Richard and Judy. In 2008, she was listed in The Observer as one of the 50 funniest acts in British comedy and won the GG2 Young Achiever of the Year Award. Her current show The Kardashians Made Me Do It is on tour at the moment.

Shazia Mirza is an award-winning comedian and columnist. TV Appearances include: Have I Got News For You, F*** Off, I’m a Hairy Woman, NBC’s Last Comic Standing and Richard and Judy. In 2008, she was listed in The Observer as one of the 50 funniest acts in British comedy and won the GG2 Young Achiever of the Year Award. Her current show The Kardashians Made Me Do It is on tour at the moment.

Grainne Maguire is a stand up comedian and comedy writer. She has appeared on Stewart Lee’s Alternative Comedy Experience, Radio 4’s Now Show, Stephen K Amos’ An Idiots Guide, Front Row and Women’s Hour. Last year her campaign to tweet Taoiseach Enda Kenny her menstrual cycle to protest against Ireland’s abortion laws went viral.

Grainne Maguire is a stand up comedian and comedy writer. She has appeared on Stewart Lee’s Alternative Comedy Experience, Radio 4’s Now Show, Stephen K Amos’ An Idiots Guide, Front Row and Women’s Hour. Last year her campaign to tweet Taoiseach Enda Kenny her menstrual cycle to protest against Ireland’s abortion laws went viral.

Kunle Olulode is director of black campaigning infrastructure charity Voice4Change England. He is also a film historian and exhibitor and part of the BFI’s African Odyssey programming team.

Max Wind-Cowie is a writer and political consultant. He previously ran the Progressive Conservatism project at the thinktank Demos and has written for newspapers including The Guardian, and the London Evening Standard.

The upcoming winter 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine focuses on taboos and the breaking down of social barriers and will be available mid-December. Cover image by Ben Jennings.

Are there things that you just aren’t allowed to talk about at family gatherings over the holiday period? The forthcoming Winter 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine is exploring the subject of taboos and we want to hear what are the biggest taboos for discussion among your family and friends. Please fill in our international survey=.

In the magazine we’ve heard from writers all over the world: Jemimah Steinfeld investigates China’s crackdown on porn and cleavage; comedians Shazia Mirza and David Baddiel look at tackling tricky subjects in comedy; Kunle Olulode writes why he thinks racism shouldn’t be airbrushed from films; Alastair Campbell explains why we can’t be silent on mental health. Plus global cartoonists, including Osama Eid Hajjaj, Bonil, Martin Rowson and Dave Brown, illustrate a range of taboos, from domestic violence to nudity and death.

All these forbidden topics got the magazine team thinking — what are the subjects that we’ll be biting our tongues about at holiday gatherings? Don’t mention migrants around Uncle Seamus? Or equal rights around Uncle Jack? Will Auntie Mary be offended by your mentioning that you think that the royal family should pay tax? Or is no one allowed to mention that story about the cousin who ran away to join the circus?

Tell us your personal taboos.

Interested in global taboos? Order your copy of the magazine here, or take out a digital Christmas gift subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year).

[gravityform id=”16″ title=”false” description=”false”]