20 Jun 2014 | News, Volume 43.02 Summer 2014

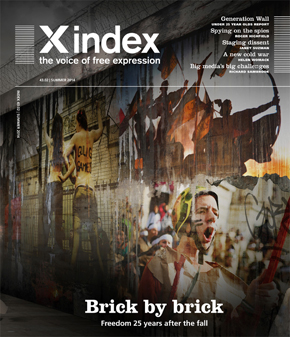

A woman chips away at the Berlin Wall, November 1989. Credit: Justin Leighton / Alamy

Our latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine includes a look at “Generation Wall” – the young people who grew up in a free eastern Europe. Tymoteusz Chajdas, 23, from Poland, is one of our contributors. Here, he looks back at what has changed and remembers his family’s excitement when packages arrived from an uncle in the West

The delivery of a package, the size of a small fridge, from abroad was rare in 1980s Poland. My family was fortunate enough to have this privilege. Every month, my two-year-old sister, Joanna, sat on the rubber flooring in the hallway of our two-bedroom apartment. She waited for a package from Jerzy, my uncle who lived in Cologne, West Germany.

The unpacking was always an occasion. But my parents have a particularly strong memory of the first time a package was delivered. When the postman arrived, Joanna opened the box and immediately started playing with the contents. “Balls. I’ve got so many! Come play with me!” It was the first time my sister had seen oranges.

This was the reality of that time. Poland became isolated from the rest of Europe when the Soviets erected the Berlin Wall in 1961. The ideals of liberty, freedom and democracy remained unattainable for an average Pole for the next 28 years. Some only experienced these ideals remotely by having family in the West, and occasionally receiving “samples” of what Western life was like.

Over on the eastern side of the wall, Poles couldn’t buy basic material goods easily, such as food or hygiene products. Large chunks of everyday life consisted of tedious searches and hours standing in long lines to buy essentials. Store shelves were frequently empty, and it seemed the only item always in stock was vinegar. Even if a product was available, it could only be purchased upon presentation of a ration card.

“Jerzy was devastated by this,” says my mother, Jadwiga, talking about her brother. In 1979, my uncle was invited by a friend for a three-week holiday in the Netherlands. After two weeks, Jerzy decided to stay on the other side of the wall. He applied for political asylum and never came back.

“He could stay there under one condition: he had to reject Polish citizenship,” she tells me. “So he did. Within two years he started sending us food and clothing.”

A few years later, another relative of ours emigrated to the United States. While the Berlin Wall divided Europe into two worlds,

Poles could not reveal any connections they had with the West. It was around this time my father started his career at the Silesian Police Department.

“We started to fear our own shadows,” says my mother, remembering that having family in the West was both a blessing and curse. Any association with capitalist Europe posed a threat to the authorities of communist Poland and was seen as political espionage and violation of the communist ideology. “[Your father] had to renounce family mem- bers living in the West if he wanted to stay employed,” says my mother. “Our phone was tapped so we had little contact with them.”

Despite this, my family still received packages. Only those who worked two jobs or were communist party members could afford to live comfortably, so my mother had to lie about her income to cover up for the extra goods we received from relatives abroad.

Less privileged Poles had little or no un- derstanding of what life looked like on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Jolanta Sudy, a high school teacher and family friend, re- members those times very well. She says the majority of Poles were victims of communist propaganda and were unaware of what was happening in their own country.

“As far as censorship is concerned, the Soviets presented the Eastern Bloc as an El Dorado where everything was perfect and no problems existed,” she says. The government spread its ideology through newspapers, magazines, books, films and theatre productions. Popular radio and tel- evision broadcasts were also censored and reinforced the views of the communist party.

Every year on 1 May, all Polish citizens were obliged to attend a street parade celebrating the International Worker’s Day. A register of attendance was kept.“It looked like a country fair or circus,” recalls Sudy. “Everyone was dressed up to show how joy- ful it was to live in Poland, how happy we were because of the socialist system. But the party stood above us with a whip.”

The elections worked similarly and at- tendance was also mandatory. Many saw them as an ironic spectacle organised by the authorities. The ballot paper featured only one name. “I always signed the register but I never put the card in the box,” says Sudy. “This was my battle with communism.”

Such oppression, constant fear and invigilation had a strong influence on the Poles. Some listened to Radio Free Europe, which broadcast unbiased news from Western countries.

In 1989 the situation changed drastically: the Berlin Wall was torn down.

“The store shelves filled up again with foreign goods,” says my mum. “Travel agents started organising vacations to other coun- tries. This was very difficult before then.”

Some Poles found the change shocking. Sudy says that, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the amount of uncensored news was overwhelming. “It was hard to believe that we could have lived differently since the end of World War II.”

The overturn of the uniform culture of communist Poland gave birth to a cul- tural explosion which had skillfully been repressed by the Soviets. Free expression in the arts in Poland did not exist during the communist period, according to Kasia Gasinska, a 24-year-old graphic designer. Some Polish citizens listened to music from non-authorised radio stations but it was only “after the wall fell down that [Polish] art became liberated,” recalls Gasinska.

Gasinska says that Western music suddenly became available in Poland, and Poles set up new bands. “New music genres were introduced, such as rave or techno, which embodied the feeling of freedom shared by many at the time.”

The collapse of communism also brought with it one of the most powerful artistic forms – street art, says Gasinska. Many Poles made the journey to the remnants of the Berlin Wall where they could freely express themselves through graffiti.

This expanded as an artistic movement to major cities in Poland. Lodz, the third largest city and a post-industrial centre, became one of many hubs for street art, famous for its colourful murals and playful graffiti that covered many bleak estates.

olish cinema was liberated from communist propaganda as well. There were new movies that referred to the Polish romantic ideals of the previous epoch, as well as comedies and films that dealt with everyday life in the wake of the political transformation.

Today, the events that led to the dismantling of the Berlin Wall seem like a distant memory for many young Poles, myself included. I was born in 1990 and I only learnt about those times by listening to the stories my parents told. Some were scary, some funny. But mostly, they feel unreal, as does the idea of getting shot at for attempting to cross the western border.

Although the Berlin Wall was torn down 25 years ago, divisions can still be felt. An in- visible wall divides us into those who are too young to remember and those who suddenly woke up in a capitalist country. Some made up for the lost time and found themselves in the new system. Others still tend to talk about the good old communist times when the pace of life was less hectic.

But even these Poles wouldn’t deny that the Berlin Wall has become a symbol of an unrealistic system, gradual economic decline and political oppression. Today, its ruins remind me of the adversities many eastern Europeans had to go through to experience living in a free, democratic country. Few remember that, at the time, only hope kept the Poles dreaming of a better life.

My mother told me that when she was a child, she received a present from her friend who was leaving for West Germany. “It was a pair of knee-high socks with blue and red stripes at the top. Today, I would say they were unsightly,” she says. “But back then, I wore them every day. Every time I looked at them, I promised myself that it was going to be better one day.”

This article appears in the summer 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Get your copy of the issue by subscribing here or downloading the iPad app.

17 Jun 2014 | News, Volume 43.02 Summer 2014

Former President of Poland Lech Walesa talks to the media at the Fallen Shipyard Workers Monument in Gdansk. (Photo: Michal Fludra/Alamy)

Poland had the largest alternative press on the eastern side of the Iron Curtain – and journalists couldn’t wait for the arrival of democracy. But after its heyday in the early 90s, the Polish media have lost their willingness to take on the powerful, argues Konstanty Gebert, who has kept a printing press, just in case. This an abridged version of an article from the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine – an “after the wall” special. For more, subscribe here

Twenty five years ago, as the round-table talks in Warsaw between the communist government and the opposition moved forward in the transition to democracy, the courtyard of Warsaw university became a print-lovers’ paradise. All kinds of underground publications, from books to newspapers, previously distributed only under the cover of secrecy, circulated in the open, provoking delight, outrage, concern and shock from passers-by. Watching vendors hawking my own publication, the fortnightly KOS, I grappled with the idea that we might actually become a normal newspaper, sold at newsstands and not in trusted private apartments, competing for newsprint, stories and readers in a free market of commodities and ideas. My only concern was that the promise of liberty would again prove a false dawn. I decided that, if we were to go “overground”, we should stash all our printing equipment and supplies somewhere, ready to pick up our clandestine work again if the political situation soured. This, to my eyes, was the greatest threat. Little did I know.

The alternative press had been both the backbone of the underground and one of its most distinctive features: no other communist country had an output that matched Poland’s. The Polish National Library has collected almost 6,000 different titles for the years 1976 to 1989 and the estimated number of readers is assessed at anything from 250,000 upwards. In 1987, KOS published a circular, issued by the regional prosecutor in the provincial industrial town of Płock. It informed his staff that if, during a house search (in a routine criminal investigation, not a political case), no underground publications were found, they needed to assume the inhabitants had been forewarned and had the time to clean up. In other words, the communist state assumed that the absence, not the presence, of underground publications in a typical Polish household was an anomaly that demanded an explanation.

This meant that, when the transition initiated by the round-table talks rushed forward at an unexpectedly speedy pace, we actually had trained journalists ready to take over hitherto state-controlled publications and, more importantly, set up new ones from scratch. The daily Gazeta Wyborcza (the Electoral Gazette was set up to promote Solidarity candidates in the first, semi-free elections of June 1989, but continued beyond that), which proudly advertised itself as the first free newspaper between the Elbe and Vladivostok, became an instant hit. Many formerly underground journalists, including myself, joined the paper, making it, for a while, a collective successor of the entire underground press. Its print run, initially limited by state newsprint allocations to 150,000 copies, soared to 500,000 once the remains of the communist state had been dismantled, and then dropped to under 300,000, as print media lost readers.

The newspaper’s unparalleled success (also financial: its publisher Agora went public in 1999 and shares initially did well) was due both to the extraordinary importance attributed under communism to the printed word and to the belief that the paper expressed “the truth” as opposed to “the lie” of the communist media. Under the government’s tightly controlled system of public expression (everything, down to matchbox labels, had to clear censorship), reality was defined by what was written, not by what was witnessed.

The underground press described a reality totally at odds with the image presented in the official media, yet validated by everyday experience: it was therefore “true”, and this exposed the communists as liars, who, moreover, were powerless to do anything about being exposed, since underground media continued to flourish, police repression notwithstanding. At the same time, the underground press was if not a propaganda venture at least an advocacy one, devoted not to the objective and non-partisan discussion of reality but to the promotion of a political current: the anti-communist opposition. Then we saw no contradiction in considering ourselves independent while supporting Solidarity candidates.

This contradiction was to explode shortly after. In 1990, barely a year after the transformation began, the first democratic presidential elections pitted Solidarity leader Lech Wałesa against his more politically liberal former chief adviser and first non-communist prime minister, Tadeusz Mazowiecki. The unity of the anti-communist movement did not survive the defeat of its adversary – and rightly so. Gazeta Wyborcza endorsed Mazowiecki, to the outrage of many of its readers, even if they, too, voted mainly for the former PM. “Your job,” one reader wrote, “is not to tell me how to vote. Your job is to give me information so I can make up my mind myself.” The newspaper could no longer count on the uncritical trust of its readers, yet it kept the position of market leader, a rarity for a quality newspaper, until it was dethroned in 2003 by tabloid Fakt.

Gazeta Wyborcza has also become the most reviled paper, at least to its adversaries in the right-wing press. The Wałesa-Mazowiecki split exposed a deep structural fissure inside the anti-communist camp, between the conservative-nationalist Catholics, who endorsed the eventual winner, and the liberal-cosmopolitan secularists, who supported the former PM. As this fissure grew (deep internal divisions within both camps notwithstanding, and regardless of their shared hostility to the former communists), Gazeta Wyborcza became, in the eyes of the right, the embodiment of an alleged “anti-Polish” project – the fact that editor- in-chief and former political prisoner Adam Michnik is Jewish was sometimes proof enough – that had to be destroyed at all costs. The declining fortunes of the newspaper in recent years have been taken by the right as proof that Poland is now “finally becoming truly independent”.

An unexpected challenge came from the former spokesman of the communist government, Jerzy Urban, who in 1990 launched his weekly publication Nie (“no” in Polish). As Urban had been easily the most hated man in Poland, his enterprise was considered doomed in advance by most – and yet Nie proved vastly successful, claiming print runs of 300,000 to 600,000 (no independent audit was available, but these estimates are credible). The weekly publication – a mixture of Private Eye-style satire, hard porn, vulgar language and excellent investigative reporting – became an instant hit, because it concentrated on a major area neglected in the anti-communist media: the anti-communists themselves. Gazeta Wyborcza and other new or restructured media had been derelict in their duty of investigating their friends in power with the same determination and mis-trust we had previously applied against the communist authorities. This was true of our coverage not only of government, but also of the Catholic church. Remembered as a victim of communist persecution and as an ally and protector of the underground (even if the reality had been more complex), trusted and revered by the overwhelming majority of the nation, the church was really beyond public criticism. Urban rightly saw in that a potential killing.

And he went after anti-communist ministers and Catholic bishops with a vengeance that struck a chord, not only among the (substantial) former-communist readership, but also among many ordinary readers, who saw in the new authorities more of a continuation of the powers-that-be of old than we would care to admit. Even if uniformly vulgar and occasionally misinformed, his criticisms were painful and to the point. The mainstream media eventually caught up, investigating the secular and ecclesiastical authorities as they should, and, eventually, pushed Urban into a niche of spiteful readers, who appreciate his vulgarity more than his incisiveness; his weekly has a current print run of around 75,000. But it took the twin lessons of the internal political split in Solidarity and the unexpected success of a seemingly compromised propagandist to force mainstream media to understand the basic obligations of their job.

In broadcasting, changes were less dramatic, as there were no trained cadre of independent radio or TV journalists to replace the old hacks: there were hardly any underground broadcast media. More importantly, the new governments, left and right, proved just as reluctant as their predecessors to give up on controlling TV, in the unfounded belief that this helps one win elections. In fact, only one government has been re-elected in the past 25 years, even though all have had as much control over state TV as they wanted and private TV has generally been politically timid. Pressure on radio was much less obvious, and private radio stations have flourished. The most successful one is perhaps Radio Maryja, a Catholic fundamentalist broadcaster, sharply critical of democracy and European integration, and long accused of producing anti-semitic content. From being the object of criticism of the church establishment for its independently extremist line, it has become its de facto mouthpiece: it can get dozens of people out on the street and get MPs elected.

Overall, however, the underground era and the first few years after 1989 were probably the heyday of Polish journalism. But from a high point of newspapers being the visible incarnation of collective political triumph, we have come to a situation when readers read little, trust even less, and believe that media have mainly entertainment value at best, and represent a hostile power run amuck at worst. New media, though immensely popular due to high internet access (53.5 per cent), still run into the problems of bias and low credibility. The printing equipment I had stashed away a quarter-century ago still gathers dust in a Warsaw cellar, its technology as remote from today’s electronic potential as the medium it produced is from today’s media.

Konstanty Gebert is a Polish journalist. He has worked at Gazeta Wyborcza since 1992 and is the founder of Jewish magazine Midrasz. He was a leading Solidarity journalist, and co-founder of the Jewish Flying University in 1979.

This article appears in the summer 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Get your copy of the issue by subscribing here or downloading the iPad app.

13 Jun 2014 | Events, Magazine, Volume 43.02 Summer 2014

Flourishing, inclusive and just – or blisteringly unequal, subtly repressive and endemically corrupt? Debating freedom 25 years after the fall.

Flourishing, inclusive and just – or blisteringly unequal, subtly repressive and endemically corrupt? Debating freedom 25 years after the fall.

In 1989, the border separating eastern and western Europe opened as communism collapsed. Twenty-five years after the event that came to symbolise the end of the Cold war, our latest magazine explores how the continent has changed. Are any of us truly freer now than we were then?

Join us for a summer drinks reception on the beautiful terrace of the Goethe Institut and a lively Question Time-style discussion, chaired by editor of Index on Censorship magazine Rachael Jolley.

Featuring:

• David Edgar, playwright

• Timothy Garton Ash, historian, author of The Magic Lantern and The File

• Martin Roth, director of the V&A, former director Dresden State Art Collections

• Polish philosopher and LGBT activist Tomasz Kitlinski

• Kate Maltby, editor Bright Blue Magazine and journalist

• Sebastian Borger, German author and journalist

When: Thursday 10th July, 6:00 reception, 6.30-7.30pm event, drinks after

Where: Goethe Institut, Exhibition Road, London, SW7 2PH (Map/directions)

Tickets: Free, registration is required as space is limited.

@IndexEvents – #AfterTheWall

BRICK BY BRICK launches the summer edition of the Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine for one issue or for the entire year and in print, online or by app.

Presented in partnership with

12 Jun 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, Magazine

Twenty five years ago this autumn the Berlin Wall was pulled down and a wave of euphoria swept not just across that city, but across Europe, and then the world. When, also in 1989, Francis Fukuyama wrote we were seeing the “end of history” it seemed to make sense. His essay suggested not that history was over, but a new era was coming, one in which liberal democracy had defeated authoritarianism and the world would now inevitably become more free.

In the wake of the fall, eastern European nations swapped authoritarian regimes for democratic governments. And people who lived behind that wall were now able to travel more easily, read news that had previously been censored, and listen to music that had been forbidden. Many got the chance to vote in their first free election, with a choice of parties, and even had the option not to vote at all.

Bricks were falling and barriers were coming down as that long line of wire and sentry posts that had divided a continent was dismantled.

A quarter of a century on and the bubble of optimism is deflating. The two world superpowers of the 1980s, the US and Russia, are squaring up again, with presidents Putin and Obama exchanging threats and counter threats. In parts of the former Soviet Union little appears to have changed for the better with attacks on gay people, anti-gay legislation and the introduction of blasphemy and anti-swearing laws. In Belarus and Azerbaijan the hope for freedom still exists, but an atmosphere of fear prevails. Journalists there still live in fear of being beaten up, imprisoned or put under house arrest for writing articles that report problems that dictators would rather not have reported. Internet restrictions stop news being distributed, and samizdat, the opposition’s underground newspapers of the Soviet era, continues to exist in Belarus. Further west of Moscow things are better than they were. Freedom to travel, write and read what you want came with the new era. But there are ominous signs. In Hungary there has been a rise in discrimination against minority groups such as the Roma, swastikas painted on Jewish gravestones, and a rise in support for fascist groups. In Poland there are similar reports of upsurges in extremism and homophobia. That initial post-wall swell of enthusiasm for change has been replaced by cynicism and anxiety.

Across Europe a strand of nasty nationalism is striding into the political arena. And weeks after Russia occupied Crimea, and continues to stand at the redrawn borders of Ukraine, the European landscape looks almost as anxious and divided as it did in the days of presidents Reagan and Brezhnev. Fears about a new Cold War feel well founded. If history teaches us anything, it should teach us to expect situations to repeat themselves, and to learn from the past.

History is certainly playing a part in these cycles. The narratives of hate often use a rewriting of history to make their case. “Those people hated us, so now we can hate them,” argues one set. “They supported the Nazis in the war,” argues one more. “The Jews might have had it bad, but it was just as bad for the non-Jewish Poles,” argues another.

A new memorial to a pro-Nazi leader in Hungary has been erected, and writers with far-right connections are now on the country’s school curriculum. Austerity has given the nasty nationalists an opportunity to tell a new story about Europe. It’s too open; it’s too competitive for jobs; our young people don’t have enough opportunities; it’s all the fault of (a group can be named here). And all this creates distant echoes of German voices in the 1930s. Austerity and high levels of unemployment open up an angry fear of a troubled future where people will have less than they have now, often an excuse for popular support for repressive legislation. Politicians and wannabe politicians are drawing out emotional memories of Russia’s fight against the Nazis; WWII victories; and myths of Russia resplendent in centuries past or Hungary split and defeated, then mixing with nostalgia, a cupful of anger and a return to religiosity, in some cases, to present the case for tighter drawn laws that ban free speech or allow states to clampdown on groups they don’t like.

The past is being rewritten.

So, have the expected gains been as nought? In her article for this issue, Irena Maryniak argues that the dividing line in Europe still exists, but it has now shifted further east, along the eastern border of the Baltic states and down the western border of Belarus. To the east there is a greater expectation of conformity and that the group is greater than the individual. There are fault lines where tensions explode and where the push and pull from decades and where arguments about national identity and geo-political pressures result in sudden uprisings and anger. Meanwhile, Konstanty Gebert, who was a leading Solidarity journalist and continues to work as a writer, charts the public’s disillusionment with the “free” press in Poland. He explores why the newly independent media was not as willing to investigate stories as objectively as it should have done, and how people’s trust in the media has dissolved.

Our three German writers on the post-wall era explore different themes. Crime writer Regula Venske looks at the expectation that Germany would have a cohesive national identity by now, but her exploration through crime novels of the country’s image of itself shows a nation more comfortable with itself as regional rather than national. Matthias Biskupek looks back at theatre and literature censored in the former East Germany; while academic and writer Thomas Rothschild has felt his optimism ebb away. Meanwhile Generation Wall, our panel of under 25-year-olds from eastern Europe, speak to their parents’ generation about the past and talk about their present.

Clearly it’s not all bad news. Those members of Generation Wall are mentally and physically well travelled in a way that the older generation was not able to enjoy. They have experienced a life mostly uncensored. Freedom House’s influential Freedom in the World report shows that the number of countries rated as “free” has swept from 61 to 88, and four more than 1989 are rated “partly free”.

And as this year’s Eurovision Song Contest showed there are protests across Europe at the heavy handed tactics of Russian authorities, and at their attitudes to minorities. While a Eurovision audience booing at the Russian contestants or Russia’s neighbours reducing their traditional 12 votes won’t have a long-term effect, it is a sign of an airing of opinions from traditional Russian allies. Bloc voting, so long a tradition in Eurovision, appeared to be breaking down. The end of history has not happened, but learning from the past should never go away.

This article was published in the Summer 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Flourishing, inclusive and just – or blisteringly unequal, subtly repressive and endemically corrupt? Debating freedom 25 years after the fall.

Flourishing, inclusive and just – or blisteringly unequal, subtly repressive and endemically corrupt? Debating freedom 25 years after the fall.