2 Aug 2024 | Israel, Middle East and North Africa, News, Palestine, Volume 53.02 Summer 2024

They emerge very slowly from a black hole in the background. Men and women, their faces tired, all take heavy steps. Some are dragging a bag, others have mattresses and household objects. The stage is lit in green and red, illuminating the young actors and dancers one by one, emphasising their individual suffering. The music – rapper Hijazi’s remix of the traditional Palestinian choral song Tarweeda Shamaly – repeats in a hypnotic loop to tell us that, for 70 years, the story of Palestinians has always been the same: moving forward in an exhausting and constantly uprooting process. The Palestinians call it Nakba and this dance-theatre show named The Story is Sick by the Ayyam al Masrah company, the only one active in the strip, was performed just over a year ago live in Gaza. It was a performance like no other which I saw on a reporting mission to the strip. Today it seems to rise again in tragic reality, after 7 October 2023.

The theatre has been destroyed now and no longer exists. The cast and crew have paid a horrific price for living in Gaza. Of the company’s 20 or so actors, aged between 20 and 35, many are displaced in Deir al-Balah. Only one, the stage technician, Ahmad Gheidar, decided to stay in Gaza, risking his life; a couple of actors, Mohannad and Lina, got engaged, left Gaza and did everything they could to escape to Egypt; three have died with all their families. None of the members of the company have a home to return to; their houses are all destroyed. The only thing left to the actors of Ayyam al Masrah is theatre, as the artistic director of the company, Mohammed al-Hessi recalls, constantly disturbed in the background by the buzz of Israeli drones.

For al-Hessi himself it was unimaginable that one of the play’s characters – a Palestinian, forced to abandon his home in 1967 and wander through refugee camps in the region – would be his reality a year later. Displaced from Gaza City after the Israeli bombings of November 2023, he and his wife and three daughters are searching for a fourth refuge, after Khan Younis, Deir al-Balah and Rafah.

“I am very worried,” he told Index in a series of daily voice messages that continue a dialogue that has already lasted more than six months. “There are thousands of people who continue to move by cars and donkeys like us. After being shot in the back and miraculously unharmed, I spent two months on Rafah beach in al-Mawasi. Here, at times I hoped to end it all. The cold in February was excessive and we tried to survive by somehow diluting the salty sea water for drinking. I was morally destroyed by the impossibility of giving a dignified life to my wife and my daughters, but I didn’t believe I would be forced to move again and again to get away from the bombings that reached us as far as the south of the strip”.

Al-Hessi’s fate is also that of a man unafraid to speak truth to power: inconvenient for Israel, to the point of not being able to leave Gaza for seven years now, because he raises political issues in his plays and is not afraid to highlight the impact of the Israeli occupation on Gazans’ daily life; inconvenient for Hamas because the theatre company has been the only one on the strip since 1995 that does not bow to the local powers that be. He has challenged Hamas’s moral police by putting men and women on stage as couples and has had the courage to question the Islamic values on which daily life is based, stimulating debate among spectators. In the audience, men and women sit together, next to each other, condemned by Hamas authorities as a dangerous potential for “promiscuity”.

In Gaza City, the success of The Story is Sick was so overwhelming when it was first staged in February 2023 that the number of performances was doubled to 40. “People loved our show because it manages to generate a great debate between the public and the actors,” al-Hessi told Index proudly. “After the performance everyone asks questions, as if looking for a solution. And the theatre has always been full: those who saw the show brought other people, students, associates. At the debut there were 350 people in the room and there were people waiting outside, sitting on the stairs.”

For those who attended the play last spring, the atmosphere was alive with debate, pulsating even. From the stands, many were wondering about the weight of tradition on family relationships and how the Israeli occupation and segregated life on the Gaza strip made the patriarchal system and male-female dynamics more burdensome and complicated.

Hana Abd al-Nabi, a lively and dynamic actor in the company, wrote the script of The Story is Sick together with the artistic director. She explained: “In this show we faced a new challenge: it was the first year in which we added male figures to the narrators on stage because we had always entrusted the role of the narrator to a female voice and body. The audience so far had not been mixed but was mostly female only.

“We then inserted male characters into the show and encouraged the presence of young men in both to change their point of view on the topics treated in our comedies. The female character tells the story from her point of view, and the male character tells the same story from his point of view. As an author I had to split between genders: if I were a man, would my wife say a certain thing, and would she complain in a certain way? And what would I do if I were a woman? And who would be right between the two? On stage, with respect to individual stories, both genders – man and woman – are right, each from their point of view. Actually, we still find ourselves trapped in the same cultural and social pattern, from the era of the Arabian Nights to the era of social media, where our entire lives, even private, are discovered, exhibited.”

The project started with a workshop between 23 actors to understand how to tell a story. The cast of Ayyam al Masrah had gathered the voices of three generations of Palestinians from Jaffa, Haifa and all of historic Palestine. Stories of the first Intifada, the second, and life today. Stories of couples who got married or who lived together or who had a love story. Each actor brought six stories. “In this journey,” said al-Hessi, “we saw something happen in front of us: in this story of the Palestinian people there was something sick. From 1948 to today, love and life have progressively disappeared. And we saw that the future in the eyes of the young was already broken, and that each of us was torn to pieces. We saw how each event – an intifada, an offensive, a siege – had an increasingly worse effect on social life. In the difficulties of everyday life, in looking for a job, in family life: even love stories have disappeared.”

The only moment al-Hessi smiles is when he talks about his workshops in refugee camps: “Our first show in 1995 was called Mothers. 200 women came to see it, and a long discussion started there too. Instead of an hour we stayed there for three hours because all the women wanted to talk. From there we started our storytelling programme for women. Now I have built a 20-minute show that stages our displacement in which women are once again the main characters and we will have three female actors on the stage. And I wrote another script, and I have three male actors on stage: it is a show tailored to the needs of children up to 12 years of age.”

Al-Hessi’s recipe is simple. At the end of the day, his bread is life: tragic, absurd, unexpected, constantly balanced between the grimace of pain and the laughter of survival.

3 Jun 2024 | Israel, News, Palestine

Israel’s decision to seize video equipment from AP journalists last week may have been swiftly reversed but the overall direction of travel for media freedom in Israel is negative.

Journalists inside Gaza are of course paying the highest price (yesterday preliminary investigations by CPJ showed at least 107 journalists and media workers were among the more than 37,000 killed since the Israel-Gaza war began) and it feels odd to speak of equipment seizures when so many of those covering the war in the Strip have paid with their lives. But this is not to compare, merely to illuminate.

The past few days have provided ample evidence of what many within Israel have long feared – that the offensive in Gaza is not being reported on fully in Israel itself. On Tuesday a video went viral of an Israeli woman responding with outrage at the wide gulf between news on Sunday’s bombing of a refugee camp in Rafah within Israeli media compared to major international news outlets. Yesterday, in an interview with Canadian broadcaster CBC, press freedom director for the Union of Journalists in Israel, Anat Saragusti, spoke more broadly of the reporting discrepancies since 7 October:

“The world sees a completely different war from the Israeli audience. This is very disturbing.”

Saragusti added that part of this is because the population is still processing the horrors of 7 October and with that comes a degree of self-censorship from those within the media. The other reason, she said, is that the IDF provides much of the material that appears in Israeli media and this is subject to review by military censors. While the military has always exerted control (Israeli law requires journalists to submit any article dealing with “security issues” to the military censor for review prior to publication), this pressure has intensified since the war, as the magazine +972 showed. Since 2011 +972 have released an annual report looking at the scale of bans by the military censor. In their latest report, released last week and published on our site with permission, they highlighted how in 2023 more than 600 articles by Israeli media outlets were barred, which was the most since their tracking began.

In a visually arresting move, Israeli paper Haaretz published an article on Wednesday with blacked out words and sentences. Highlighting such redactions is incidentally against the law and will no doubt add to the government’s wrath at Haaretz (late last year they threatened the left-leaning outlet with sanctions over their Gaza war coverage).

The government’s attempts to control the media landscape was already a problem prior to 7 October. Benjamin Netanyahu is known for his fractious relationship with the press and has made some very personal attacks throughout his career, such as this one from 2016, while Shlomo Kahri, the current communications minister, last year expressed a desire to shut down the country’s public broadcaster Kan. This week it was also revealed by Haaretz that two years ago investigative reporter Gur Megiddo was blocked from reporting on how then chief of Mossad had allegedly threatened then ICC prosecutor (the story finally saw daylight on Tuesday). Megiddo said he’d been summoned to meet two officials and threatened. It was “explained that if I published the story I would suffer the consequences and get to know the interrogation rooms of the Israeli security authorities from the inside,” said Megiddo.

Switching to the present, it feels unconscionable that Israelis, for whom the war is a lived reality not just a news story, are being served a light version of its conduct.

In the case of AP, their equipment was confiscated on the premise that it violated a new media law, passed by Israeli parliament in April, which allows the state to shut down foreign media outlets it deems a security threat. It was under this law that Israel also raided and closed Al Jazeera’s offices earlier this month and banned the company’s websites and broadcasts in the country.

Countries have a habit of passing censorious legislation in wartime, the justification being that some media control is important to protect the military. The issue is that such legislation is typically vague, open to abuse by those in power, and doesn’t always come with an expiry date to protect peacetime rights.

“A country like Israel, used to living through intense periods of crisis, is particularly vulnerable to calls for legislation that claims to protect national security by limiting free expression. Populist politicians are often happy to exploit the “rally around the flag” effect,” Daniella Peled, managing editor at the Institute for War and Peace Reporting, told Index.

We voiced our concerns here in terms of Ukraine, which passed a media law within the first year of Russia’s full-scale invasion with very broad implications, and we have concerns with Israel too. But as these examples show, our concerns are far wider than just one law and one incidence of confiscated equipment.

31 May 2024 | Israel, News, Palestine

The following article was first published by +972 Magazine, an independent, online, nonprofit magazine run by a group of Palestinian and Israeli journalists. Index on Censorship has reported on media freedom on both sides of the conflict since the 7 October attacks.

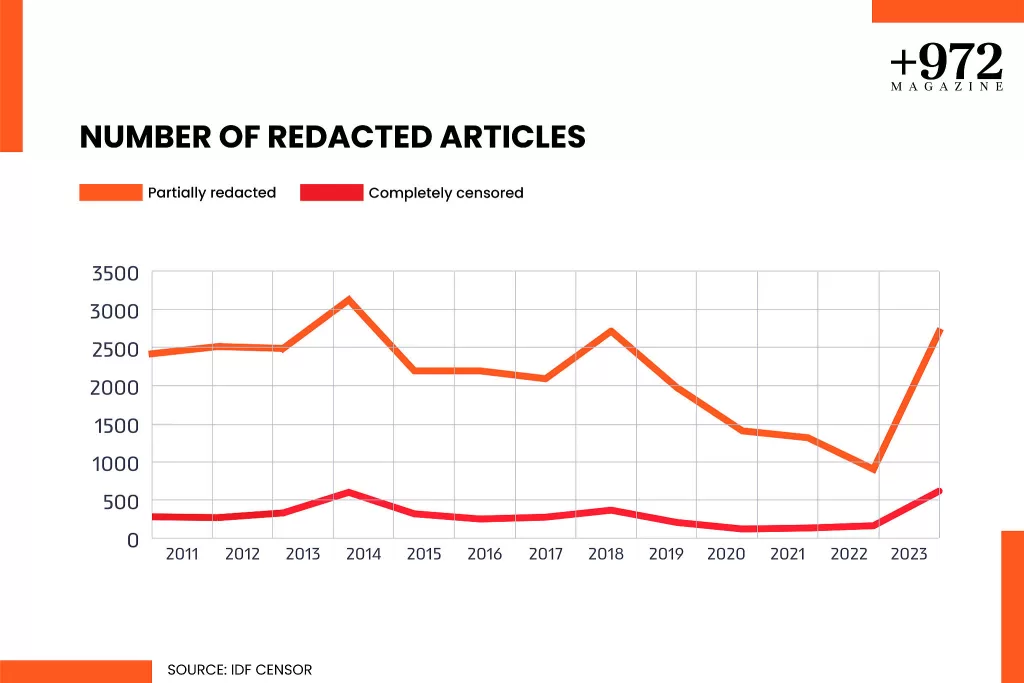

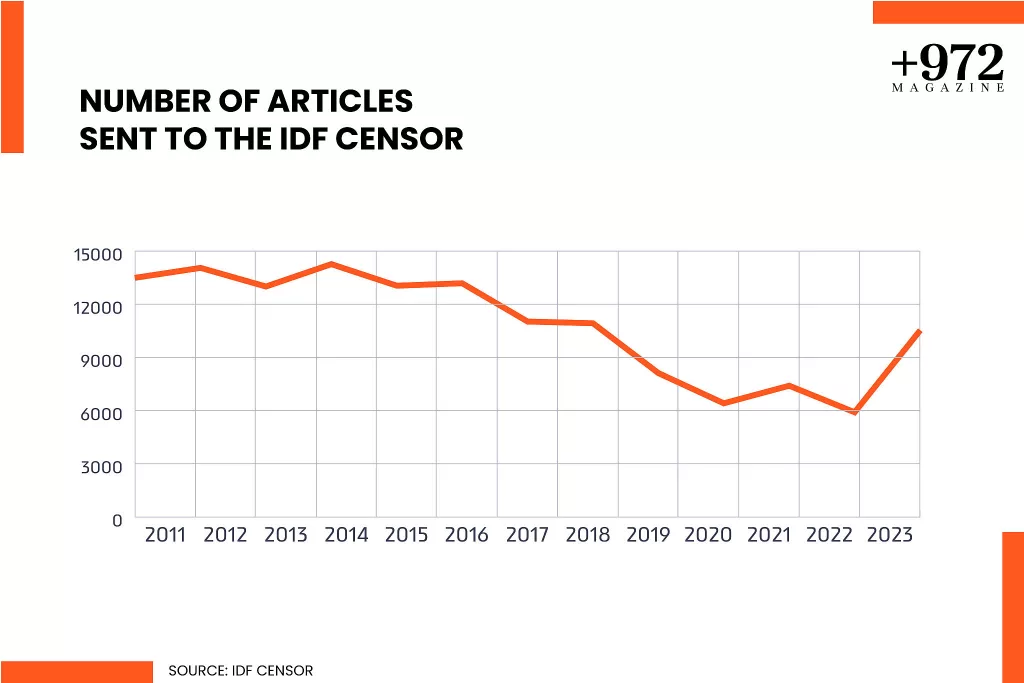

In 2023, the Israeli military censor barred the publication of 613 articles by media outlets in Israel, setting a new record for the period since +972 Magazine began collecting data in 2011. The censor also redacted parts of a further 2,703 articles, representing the highest figure since 2014. In all, the military prevented information from being made public an average of nine times a day.

This censorship data was provided by the military censor in response to a freedom of information request submitted by +972 Magazine and the Movement for Freedom of Information in Israel.

Israeli law requires all journalists working inside Israel or for an Israeli publication to submit any article dealing with “security issues” to the military censor for review prior to publication, in line with the “emergency regulations” enacted following Israel’s founding, and which remain in place. These regulations allow the censor to fully or partially redact articles submitted to it, as well as those already published without its review. No other self-proclaimed “Western democracy” operates a similar institution.

To prevent arbitrary or political interference, the High Court ruled in 1989 that the censor is only permitted to intervene when there is a “near certainty that real damage will be caused to the security of the state” by an article’s publication. Nonetheless, the censor’s definition of “security issues” is very broad, detailed across six densely-filled pages of sub-topics concerning the army, intelligence agencies, arms deals, administrative detainees, aspects of Israel’s foreign affairs, and more. Early on in the war, the censor distributed more specific guidance regarding which kinds of news items must be submitted for review before publication, as revealed by The Intercept.

Submissions to the censor are made at the discretion of a publication’s editors, and media outlets are prohibited from revealing the censor’s interference — by marking where an article has been redacted, for instance — which leaves most of its activity in the shadows. The censor has the authority to indict journalists and fine, suspend, shut down, or even file criminal charges against media organizations. There are no known cases of such activity in recent years, however, and our request to the censor to specify its indictments filed in the past year was not answered.

For more background on the Israeli military censor and +972’s stance toward it, you can read the letter we published to our readers in 2016.

“Information pertaining to censorship is of particularly high importance, especially in times of emergency,” attorney Or Sadan of the Movement for Freedom of Information told +972. “During the war, we have [witnessed] the large gaps between Israeli and international media outlets, as well as between the traditional media and social media. Although it is obvious that there is information that cannot be disclosed to the public in times of emergency, it is appropriate for the public to be aware of the scope of information hidden from it.

“The significance of such censorship is clear: there is a great deal of information that journalists have seen fit to publish, recognizing its importance to the public, that the censor chose not to allow,” Sadan continued. “We hope and believe that the exposure of these numbers, year after year, will create some deterrence against the unchecked use of this tool.”

A wartime trend

Although the censor refused our request to provide a breakdown of its censorship figures by month, media outlet, and grounds for interference, it is clear that the reason for last year’s spike is the Hamas-led October 7 attack and the ensuing Israeli bombardment of Gaza. The only year for which there was a comparable level of silencing was 2014, when Israel launched what was then its largest assault on the Strip; that year, the censor intervened in more articles (3,122) but disqualified slightly fewer (597) than in 2023.

Last year, the censor’s representatives also made in-person visits to news studios, as has previously occurred during periods in which the government has declared a state of emergency, and continued monitoring the media and social networks for censorship violations. The censor declined to detail the extent of its involvement in television production and the number of retroactive interventions it made in regard to previously published news articles.

We do know, however, thanks to information revealed by The Seventh Eye, that despite the Israeli media’s proactive compliance — the number of submissions to the censor nearly doubled last year to 10,527 — the censor identified an additional 3,415 news items containing information that should have been submitted for review, and 414 that were published in violation of its orders.

Even before the war, the Israeli government had advanced a series of measures to undermine media independence. This led to Israel dropping 11 places in the 2023 annual World Press Freedom Index, followed by an additional four places in 2024 (it now sits in 101st place out of 180).

Since October, press freedom in Israel has further deteriorated, and the censor has found itself in the crosshairs of political battles. According to reports by Israel’s public broadcaster, Kan, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu pushed for a new law that would force the censor to ban news items more widely, and even suggested that journalists who publish reports on the security cabinet without the approval of the censor should be arrested. The chief military censor, Major General Kobi Mandelblit, also claimed that Netanyahu had pressured him to expand media censorship, even in cases that lacked any security justification.

In other cases, the Israeli government’s crackdown on media has skirted the censor and its activities entirely. Back in November, Communications Minister Shlomo Karhi banned Al-Mayadeen from being broadcast on Israeli TV, and in April, the Knesset passed a law to ban the activities of foreign media outlets at the recommendation of security agencies. The government implemented the law earlier this month when the cabinet unanimously voted to shut down Al Jazeera in Israel, and the ban will now reportedly also be extended to the West Bank. The state claims that the Qatari channel poses a danger to state security and collaborates with Hamas, which the channel rejects.

The decision will not affect Al Jazeera’s operations outside of Israel, nor will it prevent interviews with Israelis via Zoom (full disclosure: this writer sometimes interviews with Al Jazeera via Zoom), and Israelis can still access the channel via VPN and satellite dishes. But Al Jazeera journalists will no longer be able to report from inside Israel, which will reduce the channel’s ability to highlight Israeli voices in its coverage.

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel and Al Jazeera petitioned the High Court against the decision, and the Journalists’ Union also issued a statement against the government’s decision (full disclosure: this writer is a member of the union’s board).

Despite these various attacks on the media, the most significant threats posed by the Israeli government and military, and especially during the war, are those faced by Palestinians journalists. Figures for the number of Palestinian journalists in Gaza killed by Israeli attacks since October 7 range from 100 (according to the Committee for the Protection of Journalists) to more than 130 (according to the Palestinian Journalists Syndicate). Four Israeli journalists were killed in the October 7 attacks.

The heightened government interference in Israeli media does not absolve the mainstream press of its failure to report on the army’s campaign of destruction in Gaza. The military censor does not prevent Israeli publications from describing the war’s consequences for Palestinian civilians in Gaza, or from featuring the work of Palestinian reporters inside the Strip. The choice to deny the Israeli public the images, voices, and stories of hundreds of thousands of bereaved families, orphans, wounded, homeless, and starving people is one that Israeli journalists make themselves.

This article was previously published by +972 here.

5 Apr 2024 | Israel, News, Palestine

Almost six months to the day since the outbreak of war between Israel and Hamas, the Israeli government made a decision to shutter the Al Jazeera bureau in Jerusalem. The Knesset vote was an overwhelming 71-10. “The ability of the Communications Minister to shutter press for political motivation is a complete and utter threat to democracy in Israel,” said Noa Sattath, the director of the Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI), Israel’s leading human and civil rights organisation. “We want a journalist to be thinking about the truth, not about what a minister is thinking about them—this is a chilling effect. “

In addition to the attack on freedom of expression and freedom of the press, the new law also effectively precludes the court from intervening in decisions regarding the closure of media outlets. In addition to closing Al Jazeera’s offices, the law allows removing its website and confiscating the device used to deliver its content. Al Jazeera, termed a “propaganda machine” not a news organisation by many in the Israeli government, was an easy target perhaps, especially during wartime, but it is especially in wartime that a democracy’s fortitude is tested.

In a new sixth-month survey of the impact of the war on human and civil rights in Israel, ACRI makes these points: “Even before the terrorist attack Hamas perpetrated on 7 October, and before the war broke out, Israeli democracy was facing severe threats. Combined together, laws designed to take over the judicial system [what Prime Minister and his government called ‘judicial reform’, but what opponents called a ‘judicial coup’ attempt] and a slew of other initiatives in different areas crystallised to produce a judicial overhaul, as part of which the government sought to undermine the pillars of democracy and reduce human rights protections. Some initiatives to take over the judicial system have been put on hold since the war began, partly because this was put forward as a condition for expanding the government [by member parties]. Other initiatives that threaten democracy have also been suspended.”

Yet, there are enough new curbs and potential curbs on human and civil rights to warrant a 14-page document from ACRI. Sattath, the ACRI director, explains: “The government has pushed forward with existing trends such as targeting Arab society, restricting freedom of movement, increasing the prevalence of firearms in public spaces, and accelerating the annexation of the West Bank. Given the general climate in a time of war, these efforts are met with less resistance. In other fields, such as prisoners’ rights, the state of human rights has taken a significant turn for the worse, while the public remains entirely indifferent. Human rights violations are often carried out via emergency regulations (Hebrew), an undemocratic tool that allows the government to enact laws, seriously violating the principle of separation of powers.”

In addition to the actual censoring of media, the mainstream media has self-censored in Israel, aware of—and even setting—the tone among the public. Nightly newscasts cover soldiers in the field, the hostages, and other security concerns but rarely focus on the situation for Palestinians, including the humanitarian concerns in Gaza.

Additionally, people have been detained by the police for a “like” on social media after the Ministry of Justice removed the State Prosecutor’s oversight on charges for offences of freedom of expression during the war, so that police don’t need approval before investigating such cases. Police were directed to detain people for social media posts until the proceedings’ end and prosecute them even for a single publication. This change led to a surge in arrests of Arab citizens regarding social media posts; arresting without cause.

Meanwhile, there is a proliferation of widespread hate speech online incriminating Jewish social media spots promoting hate against Arabs, but enforcement disproportionately targets Arab citizens and residents.

By November, there were 269 investigation cases for incitement and support for terrorism, resulting in 86 expedited indictments for incitement to violence and terrorism. Suspects faced prolonged detention and even remand until trial, a departure from due process.

Additionally, there are significant violations of policing of peaceful demonstrators, along with unlawful detentions of protesters and unauthorised visits to the houses of suspected protest organisers by the police. The police (which is federalised in Israel), led by far-right minister Itamar Ben Gvir, seem to be pre-imagining what steps he anticipates for them and taking them–all with no retribution so far.

Security prisoners in Israeli prisons have faced much worse, with protocols, including lawyers’ visits, upended. Meanwhile, there is a proliferation of guns in the streets with a free-for-all dispensation by Ben Gvir’s office to create private militias both inside Israel and in the Occupied Palestinian Territories where actions by Jewish settlers against Palestinian residents have multiplied.

These are just a few key examples of what Israelis are facing. Even when the war ends and when the current government falls, much of the backtracking in Israeli society will be hard to reverse.