1 Jul 2020 | China, News, Student Reading Lists

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

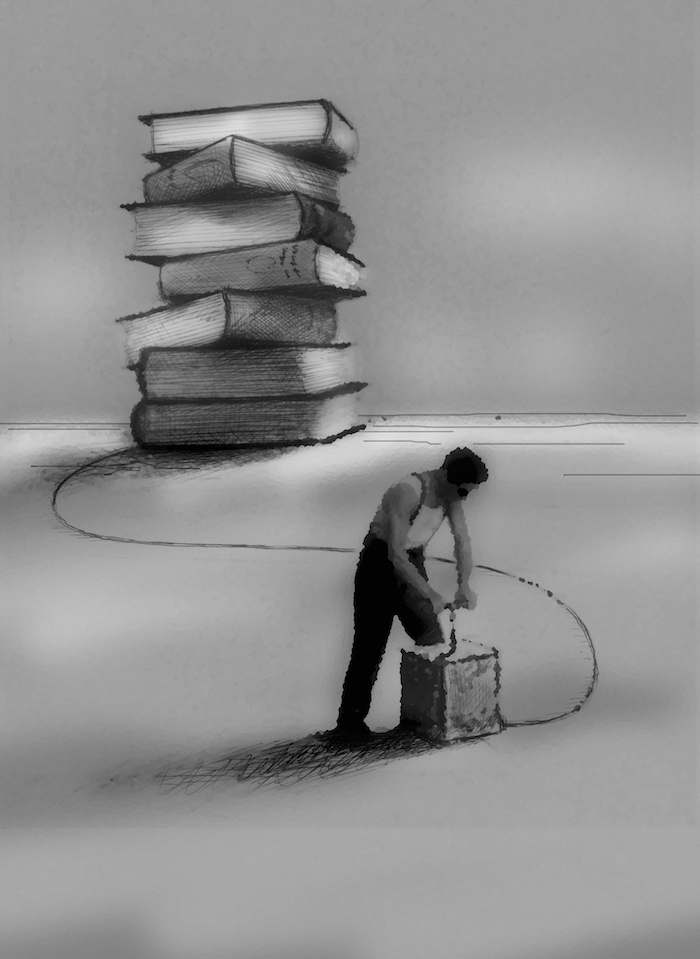

Illustration from cartoonist tOad published today in response to the new law. twitter.com/t0adscroak, www.unsitesurinternet.fr

The National Security Law passed on 30 June in Hong Kong has dealt a massive blow to the city’s status as an autonomous region into which the Chinese government’s suppression of freedom of expression doesn’t encroach. The new law will criminalise “any act of secession, subversion of the central government, terrorism or collusion with foreign or external forces”.

Language like this, as those on the mainland may have experienced, could be manipulated to apply to any behaviour the Chinese government doesn’t like, leaving journalists, activists, protesters and campaigners at risk. Activists in Hong Kong have already begun to shut down their operations out of fear of reprisal in the wake of the law.

Since 1997, when Hong Kong was handed back to China having previously been a British colony, Hongkongers have enjoyed freedom of expression, including a flourishing free press, under the “one country, two systems” constitutional principle. As this principle begins to crumble, we look back at pieces published in Index magazine in 1997 which explored the implications of the handover and the future relationship between mainland China and Hong Kong.

In this edited version of the speech given by Professor Helen Fung-Har Siu in Hong Kong in 1996, she explored the national identity of Hong Kongers and how it intersected with the oppressive nature of the Chinese authorities. In the years preceding the 1997 handover, the people of Hong Kong enjoyed freedom of expression; Siu noted that one in six people there marched in protest at the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre. Dissecting the socioeconomic developments in Hong Kong through the 1970s and 80s, Siu questioned how the region and its people, who are accustomed to independence from China, would adapt to its new relationship with the People’s Republic.

Published in early 1997 in anticipation of the handover, Geremie R Barmé, author of Shades of Mao: The Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader, wrote on the flow of popular culture from Hong Kong and Taiwan to mainland China through the 1980s. He explored how the lure of Beijing’s culture waned through the 70s, leading people to soak up the film and music coming from the south, despite attempts by the authorities to censor it. Hong Kong, independent from the Chinese authorities, acted as a conduit between the people in mainland China and Taiwan, and indeed the rest of the world. Barmé predicted that, as Hong Kong returned to China, the subsection of society supporting communist ideals would be brought to the fore by the mainland.

He wrote: “The patriotic significance of Hong Kong’s return to the mainland is lost on no-one. It is part of the final process of what the Communist authorities, and many people in China, see as the reunification of a divided nation.”

Ma Jian, an artist who left Beijing for Hong Kong in 1990, shared his feelings of liberation as he crossed the border and reflects on the suppression of his art on the mainland. Demanding rights and freedom from the Chinese authorities was, he wrote “like being on a battlefield”. Jian wrote that he would remain in Hong Kong after the handover, but projected a lack of optimism about his future freedoms.

“As we watch, incredulously, pre-ordained history advances, or rather, steps backwards to meet us,” he wrote. “No-one asks whether we accept the past, whether we can go and live the time we have already lived. It is as though, studying at middle school, we are suddenly sent back to kindergarten.”

In July 1998, Edward Lucie-Smith visited Hong Kong to find out how the city was acclimatising to the handover one year on. Finding local people unwilling to discuss at length the direction freedom of speech had taken, Lucie-Smith looked to global economic developments and how they could impact Hong Kong’s political future, and in turn the future of freedom of expression. Hong Kong faced an economic downturn in 1998, along with other so-called ‘tiger-economies’, meaning the Hong Kong Chinese elite, who were middlemen between the democratic forces in Hong Kong and the Chinese authorities, may have chosen to move to other parts of the world, leaving Hong Kong and its people more at risk of being ideologically swallowed up by the mainland.

He wrote: “The general feeling was that the British were handing over an economic jewel – a financial mechanism so successful and so finely tuned that the mainland Chinese government would be foolish to interfere with its functioning. But would it be able to resist tinkering, on ideological grounds, with the ‘special economic zone’ within China that Hong Kong was now to become?”

Published in January 1997, Jonathan Mirsky, then East Asia editor of The Times, wrote on how freedom of expression began to crumble in Hong Kong in anticipation of the handover. He described how news channels reported on China in a “vapid or grovelling” manner, to avoid attempts at censorship by Chinese representatives in Hong Kong.

Outspoken democratic politicians told Mirsky how their colleagues no longer wanted to be associated with them. Organisations were expected to plan celebrations for the handover, and comply. Mirsky predicted a dismal future for Hong Kong where loyalty to the Party would be an overriding expectation.

Charles Goddard, at the time of writing a member of the Hong Kong Journalists Association, discussed Hong Kong’s position as eyes on China for the rest of the world, where issues such as human rights abuses in mainland China could be discussed and dissidents from the Chinese authorities could find a relatively safe haven. Goddard, however, highlighted the dangers to journalists in Hong Kong reporting negatively about China, predicting that the status of the city as a place where freedom of expression could flourish would only diminish.

Liu Dawen, at the time of writing the editor of Front Line magazine, took an optimistic view of Hong Kong’s future, believing that the spirit of democracy would not wane.

“In the longer term, the Party cannot stem the ‘raging tide’ of democracy indefinitely either in Hong Kong or in the People’s Republic. When things reach a certain pitch, the pendulum must swing back in the opposite direction,” he wrote.

Charting the arrests and imprisonments of Chinese journalists, Asia-Pacific researcher for Reporters San Frontieres Barbara Vital-Durand painted a picture of China as a country which cracked down harshly on outspoken dissidents from the party line. She foreshadowed a world in which, post-handover, Chinese authorities would extend the jaws of censorship to crush Hong Kong journalists, and access to the internet on the mainland would be tightly controlled.

“Journalists’ organisations and free speech groups have been unsuccessful in getting the British authorities – or subsequently China’s Preparatory Working Committee (PWC) – to abolish several legislative measures which, if left in place, will provide the Chinese authorities with some powerful weapons to use against the media,” she wrote.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”3″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1593615252756-723f64f2-cdee-10″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

12 Mar 2020 | News, Student Reading Lists

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]In August 2019 the Indian government under Narendra Modi, leader of the the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, revoked Article 370 of the Indian constitution. The article had granted the state of Jammu and Kashmir the autonomy to write their own constitution and make their own laws. Since the article was revoked, residents of Jammu and Kashmir have been subjected to the world’s longest internet shutdown, a serious breach of their right to free expression and to access information. As the ban on high-speed internet continues, Index looks back on the history of freedom of expression in India, from the years following The Emergency, to the present.

Libya: Criticise & be killed, the December 1980 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

In 1975 Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was convicted of election malpractice conducted during her 1971 campaign. Despite this, she clung onto power and declared a state of emergency which lasted for 19 months, known as The Emergency. During this time, members of the political opposition were imprisoned and the press heavily censored. In this article written in 1980, the year Gandhi was re-elected, Michael Henderson questions if Indian journalists have a long enough memory and a robust enough spirit to stand up to a prime minister with a clear and recent track record of control of the press.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Black voices in South Africa, the December 1984 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

In 1984, George Theiner writes of an India still scarred by The Emergency and a visit to Index on Censorship by Mr Justice A N Grover, chairman of the Press Council of India, who took issue with the magazine’s continuing criticism of the Indian press. Theiner interviewed journalists about the future of democracy and a free press under Indira Gandhi. He found a mixture of those who were still in shock about the censorship during The Emergency, and those who were complacent in a belief that it couldn’t happen again. (The future of India under Gandhi came to be something of a moot point as, in October 1984, a few months after this article was published, she was assassinated by her own bodyguards.)

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

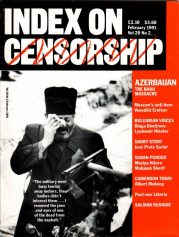

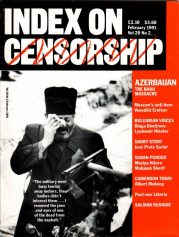

Azerbaijan: the Baku Massacre, the February 1991 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

In 1991 India had a free press… in newspapers. Television and radio were state-owned and state-exploited. Other innovative types of media became a political battleground, with opposition parties promising to release the government’s grip on a news outlet that was fast evolving. Sidharth Bhatia’s piece details the independent video magazines set up by journalists which had to be rented from a video shop. When these magazines became successful, reaching a wide audience and providing information not stifled by a state agenda, government censorship began to encroach upon them.

Read the full article [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The war of the words, the March 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Prayaag Akbar examines the role the rich and powerful have in press censorship in India, but in this case it is wealthy business owners, rather than the government, who come under scrutiny. Media outlets who find themselves owned by a large business conglomerate, may then be under pressure to self-censor in order to avoid reporting negatively on the hand that feeds them. Akbar cites examples of the collision of business interests with journalistic integrity as the richest men in India buy up large portions of the national media groups.

Read the full article

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

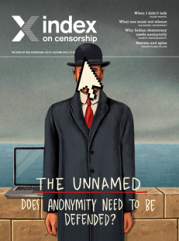

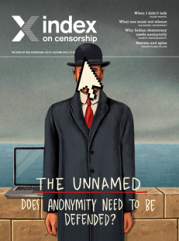

The unnamed, the September 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Is online anonymity allowing trolls to abuse women without consequences, or it is vital for the safety of those whose expression does not follow the party line? In 2016, as Twitter became more widely used in India, and issues of trolling became apparent, government ministers suggested removing the anonymity of trolls in a bid to increase accountability. Suhrith Parthasarathy reports on how state involvement with online expression could lead to the anonymity of activists being revoked to protect state interests.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

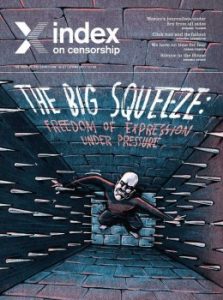

The Big Squeeze, the April 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

In November 2016, a Supreme Court order made it obligatory to stand during the national anthem, which is played in Indian cinemas before the film begins, equating being patriotic with being a law-abiding citizen. Lawyer and writer Suhrith Parthasarathy examines the legal complexities of enforcing shows of patriotism in a country whose constitution guarantees freedom of expression, and speaks to people who have been subject to police interviews for choosing to stay seated.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Is This All the Local News?, the April 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Rituparna Chatterjee reports on the importance of local news, and threats faced by local news journalists in India. Journalists working in rural parts of India can face pay too low to survive on, and can be susceptible to bribes from local police officers and politicians, keen to censor scandals. Chatterjee also highlights how tribal and indigenous communities can end up excluded from the national narrative of India when large media conglomerates do not report on issues in the areas they live in.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

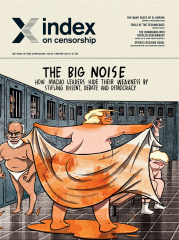

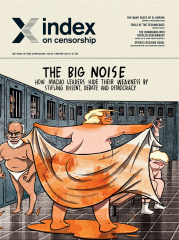

The Big Noise, the December 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

The Emergency of 1975-1977 has been seen in later years as a blip in freedom of expression in India. However, since the election of Modi to prime minister in 2014, freedom of expression in India is taking a hit. Modi’s supporters are instilling fear and committing violence against those considered outsiders, often Muslims. Such violence is not being roundly condemned by their leader; his silence is taken as tacit approval. Meanwhile the internet shutdown imposed on Kashmir has not been fully lifted, an attack on access to information.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

17 Oct 2019 | News, Student Reading Lists

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship was established in 1972 in a febrile period: Idi Amin had taken power in Uganda, the Vietnam war continued, direct rule was imposed in Northern Ireland, there was a coup in Bolivia and Congo was renamed Zaire by its dictator president. As writer Robert McCrum said in our 40th anniversary issue: “The abuses of freedom worldwide in the 1970s were so appalling and so widespread that the magazine rapidly found itself in the frontline of campaigns. Index became a clarion voice in the cause of free expression.” The right to protest and freedom of expression are now being sought in Hong Kong and elsewhere, and Index is still to the forefront in reporting abuses. Here are just some of the conflicts between freedom and dictatorship we have reported on in the past 47 years.

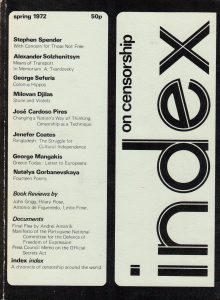

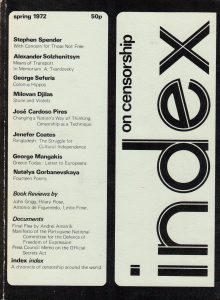

The first issue of Index on Censorship magazine, in March 1972

The Clockwork Show vol 1, issue 1, March 1972

In an anonymous article about life in Greece under the regime of the Colonels’ junta, the writer considered the psychology of the situation; the feelings and attitudes, the long-ranging impact of this harrowing experience. “There is nothing more demoralizing than to be bound to a public body, an administration, a government with which one can never for a moment identify, which is the exact opposite of everything one believes in. One cannot live side by side with Philistinism, chauvinism, bigotry, blatant hypocrisy, crass ignorance, injustice, violence and brutality and not be affected by them, even if one manages—only just—to keep them out of one’s own life. Under this regime there is no relief; no exception: the regime has penetrated every single aspect of public life.”

Read the full article

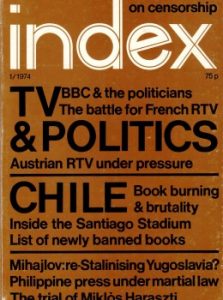

March 1974: TV, politics and Chile Index on Censorship magazine

Book burning and brutality vol 3, issue 1, March 1974

A fascinating insight into life in Chile six months after a coup ended the tyranny of President Salvador Allende: worse was to come under a military dictatorship, reported Michael Sanders, an Englishman in Santiago. “When Allende left Chile to address the UN in December 1972, a leading opposition newspaper had as its front-page a photo depicting the president flushing himself down a lavatory, with the caption ‘ good riddance’. The contrast in December 1973 is gloomy indeed. Not so much, or not only because of the drab uniformity of censored newspapers that, for all they may be censored, willingly reflect the views of the Military Junta. But for the fact that 43.6% of the population have been deprived of all means of expression, of all normal communication, and live in daily fear of their lives and jobs.”

Read the full article

Russia, East Germany, South Africa: May 1979 Index on Censorship magazine

Black journalists under apartheid volume 8, issue 3, May 1979

William A Hachten reports: Black journalists came to the fore in the Soweto riots of 1976 when they reported from the ghetto for a white press without access. Yet black journalists still faced daily harassment under apartheid, which worsened with the death of Steve Biko in 1977. Vusi Radebe, a black stringer for the Rand Daily Mail, said: “The situation is worse since the 1976 riots. Police will beat up reporters on the slightest provocation for what they consider obstruction of justice.” While whites had 23 newspapers, there were none for non-whites to express their political frustration. Black journalist Pearl Luthuli said: “The black journalist can’t be objective. We try to tell it like it is but the white editors won’t print it.” Another said: “We are black people first, journalists second. If it comes to a conflict between the struggle and the job, the struggle comes first.”

Read the full article

Beckett and Havel: Index on Censorship magazine, February 1984

Iran under the party of God, volume 13, issue 1, February 1984

“Censorship was planned by the regime of the Islamic Republic even before the February 1979 revolution brought Ayatollah Khomeini’s theocratic oligarchy to power. This particular kind of censorship may not be without precedent in history, but it must certainly be rare. There were attacks on coffee-houses, restaurants and other public places by men armed with clubs and stones; unveiled women were harassed; slogans of the opposition were cleaned from the walls; banks, cinemas and theatres were burned” – a personal account of the first years of the revolution and its attack on culture, by one of Iran’s leading writers Gholam Hoseyn Sa’edi. “And it keeps on happening. The Islamic regime of today has gone a step beyond censoring the creations of science, culture and art, beyond censoring life itself: it has rendered life vain and all but unliveable.”

Read the full article

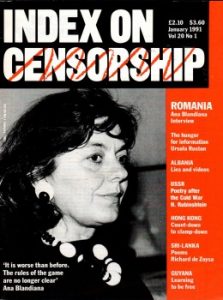

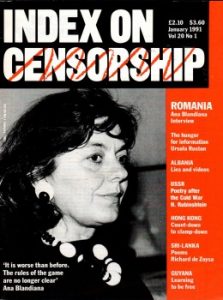

Romania, Albania, USSR: Index on Censorship magazine January 1991

A sense of solidarity, volume 20, issue 1, January 1991

Romania’s celebrated poet, Ana Blandiana, on censorship under Ceausescu and how she fought back. Her work was completely banned three times. “In my case, the form of censorship progressed from the banning of a word to that of a line, then of a poem, then of a book, to the total erasure of my signature as author: an eradication of identity. My inner freedom was assured by a decision I took in 1980, a personal one rather than as a writer. I decided to be outspoken and say what I thought at the risk of becoming a victim myself, rather than suspect a possibly honest person. At first it kept me sane, and then it helped me to be a normal writer, relatively free of self-censorship. This was the strongest form of censorship under Communism in the last 10 or 15 years, and was much more refined and subtle than the official censorship.”

Read the full article

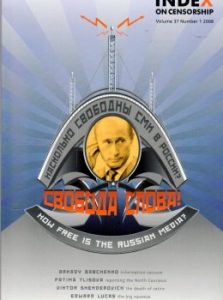

How free is the Russian media? Index on Censorship, Spring 2007

The Big Squeeze, volume 37, issue 1, Spring 2008

“The fact remains that since the departure of the oligarchs, Russian media freedom has gone from the imperfect and beleaguered to the moribund. At national television, which 90 per cent of Russians say is their main source of news, editors receive weekly or even daily instructions from the Kremlin on the ‘line to take’ on important stories; around half of Russian viewers think that what they watch is objective, a 2007 poll said. Foreign coverage is polemical and outrageously politicised. The message of all this is ‘be quiet’. If you annoy the rich and powerful you face threats, beatings or death. Even when the Kremlin is not directly involved, its reaction to the persecution of journalists sends a clear message: if you offend the powerful, don’t expect the law to protect you.” Edward Lucas gave an early taste of what freedom of expression meant under Putin.

Read the full article

40 years of Index on Censorship March 2012

Grit in the engine, volume 41, issue 1, Spring 2012

Robert McCrum on the 40th anniversary of Index on Censorship. “The success of Index was not a foregone conclusion. Stephen Spender, its founder, was fully alert to the potential for windbaggery and failure. There was, he wrote, ‘the risk that the magazine will become simply a bulletin of frustration’. Actually, the opposite came to pass. Index became a clarion voice in the cause of free expression. The abuses of freedom worldwide in the 1970s were so appalling and so widespread that the magazine rapidly found itself in the frontline of campaigns. Perhaps the most important thing Index did, from the beginning, was to universalise an issue in peril of becoming a special interest: freedom was not ‘a luxury enjoyed by bourgeois individualists’. Along with self-expression, it was a human right, and an instrument of human consciousness.

Read the full article

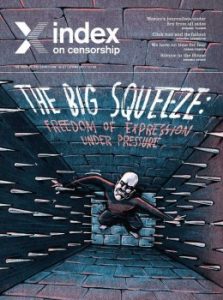

The big squeeze: Index on Censorship magazine Spring 2017

Freedom of expression under pressure, volume 46, issue 1, Spring 2017

The spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at how pressures on free speech are currently coming from many different angles, not just one. Special features on how to spot fake news, articles from former BBC World Service director Richard Sambrook and former UK attorney general Dominic Grieve, an exclusive interview with the Spanish puppeteer arrested last year, and fiction from award-winning writer Karim Miské.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Apr 2018 | Magazine, News, Volume 47.01 Spring 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

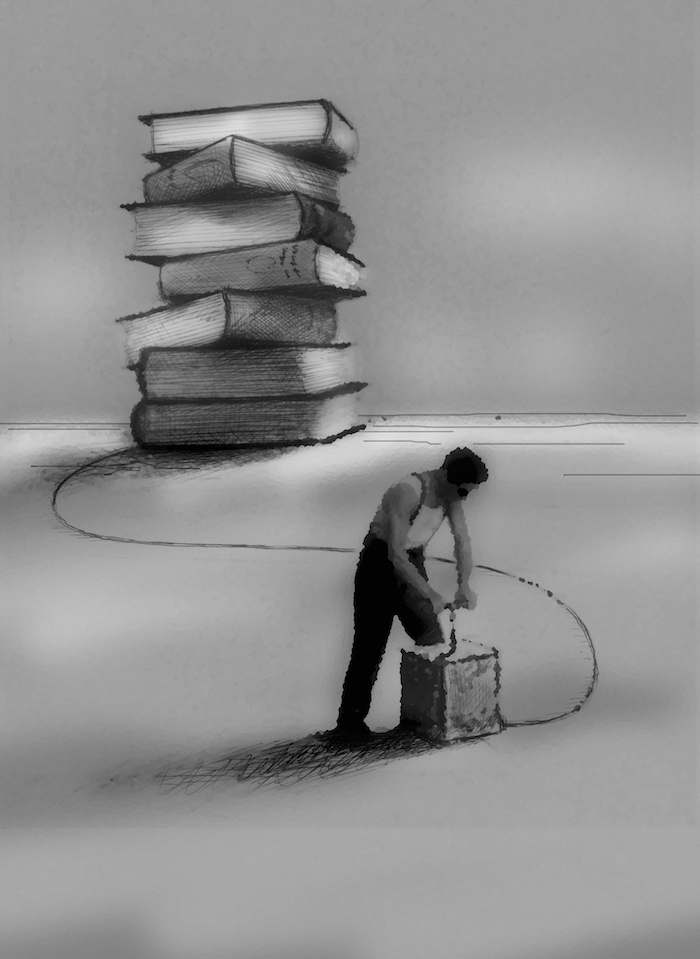

Authoritarian leaders know their history. They also know the history they would like you to know. They are aware, perhaps more than anyone else, that choosing images and stories from the past to align and amplify the ways a country is run can be a terribly powerful tool.

As Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan discussed with Index for this issue, dictators have been aware of the power of history to make their arguments for centuries. From the first Chinese emperors to today’s leaders – China’s Xi Jinping and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan, among others – the selection of historical stories which reflect their view of the world is revealing.

“The thing about history is if people know only one version then it seems to validate the people in power,” said MacMillan.

But if you know more, you can use that information to make informed decisions about what worked in the past – and what didn’t – allowing people to learn and move on.

And right now, historical validation is an active part of the political playbook. In Russia, Vladimir Putin is a big fan of the tale of the great and powerful Russia. And what he doesn’t like are people who don’t sign up to his version of history.

Even asking questions about the past can provoke anger at the top. It interferes with the control, you see.

In 2014, Dozhd TV had an audience poll about whether Leningrad should have surrendered to the Nazis during World War II. Immediately there were complaints, as Index reported at the time. The station changed the wording of the question almost immediately, but within months various cable and satellite companies had dropped Dozhd from their schedules. Question and you shall be pushed out into the cold.

From the start, this magazine has covered how different countries have attempted to control the historical knowledge their citizens receive by limiting the pipeline (rewriting textbooks or taking history off the syllabus completely, for instance); using social pressure to make certain views taboo; and, in extreme cases, locking up historians or making them too afraid to teach the facts.

In our Winter 2015 issue, we covered the story of a Palestinian teacher who took his students to visit Nazi concentration camps in Poland because he felt they should know about the Holocaust. But not everyone agreed. While he was on the trip, there were demonstrations against him, his office was stormed and his car was torched. Later there were threats against his family. To escape the danger, he and his family had to move abroad. The teacher, Mohammed Dajani Daoudi, who wrote about his experiences for the magazine, said: “My duty as a teacher is to teach – to open new horizons for my students, to guide them out of the cave of misconceptions and see the facts, to break walls of silence, to demolish fences of taboos.”

What an incredibly brave vision for a teacher to have in the face of a mob of people who would seek to damage his life, and that of his family, to show how much they disapproved of what he was trying to do.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”But censoring history is not the only way to go about establishing inaccuracies and ill-informed attitudes about the past. Another option is to spin it.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Dajani Daoudi is not alone in fighting against the odds to bring research, open thinking and a wide base of knowledge to students. But, as our Spring 2018 issue shows, the odds are starting to stack up against people like him in an increasing number of places.

In 2010, Maureen Freely wrote a piece called Secret Histories for this magazine, about Turkish laws that had kept most of its citizens in the dark about the killings of a million Armenians in the last years of the Ottoman empire, and how those laws were enforced by making certain things – including criticising the legacy of modern Turkey’s founding father, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk – illegal.

Turkey’s government today has just passed a law making mention of the word “genocide” an offence in parliament, as our Turkish correspondent, Kaya Genç, reports on page 22.

But censoring history is not the only way to go about establishing inaccuracies and ill-informed attitudes about the past. Another option is to spin it.

Resisting Ill Democracies in Europe, the excellent report from the Human Rights House Network, acknowledges that a common thread in countries where democracy is weakening is the “reshaping of the historical narrative taught in schools”. In Poland, the introduction of a Holocaust law means possible imprisonment for anyone who suggests Polish involvement in the Holocaust or that the concentration camps were Polish. In Hungary, the rhetoric of the ruling party is to water down involvement of its citizens in the Holocaust and to rehabilitate the reputation of former head of state Miklós Horthy.

At the same time as undermining public trust in the media, governments in this spin cycle seek to stigmatise academics, as well as close down places where open or vigorous debate might take place. The result is often the creation of a “them and us” mentality, where belief in the avowed historical take is a choice of being patriotic or not.

As the HRHN report suggests, “space for critical thinking, independent research and reporting and access to objective and accurate information are pre-requisites for informed participation in pluralistic and diverse societies” and to “debunk myths”.

However, if your objective is not having your myths debunked then closing down discussions and discrediting opposition voices is the ideal way to make sure the maximum number of people believe the stories you are telling.

That’s why historians, like journalists, are often on the sharp end of a populist leader’s attack. Creating a nostalgia for a time where supposedly the garden was rosy and citizens were happy beyond belief often forms another part of the political playbook, alongside creating a false history.

Another tactic is to foster a sense that the present is difficult and dangerous because of change and because of threats to “traditional” values; and a sense that history shows a country as greater than it is today. The next step is to find a handy enemy (migrants and LGBT people are often targets) to blame for that change and to stoke up anger.

Access to the past matters. Knowledge of what happened, the ability to question the version you are receiving, and probing and prodding at the whys and wherefores are essentials in keeping society and the powerful on their toes.

In this issue of Index on Censorship magazine, we carry a special report about how history is being abused. It includes interviews with some of the world’s leading historians – Lucy Worsley, Margaret MacMillan, Charles van Onselen, Neil Oliver and Ed Keazor (p31).

We look at how history is being reintroduced into schools in Colombia (p60) and how efforts continue to recognise the victims of General Franco’s dictatorship in Spain (p72). We also ask Hannah Leung and Matthew Hernon to talk to young people in China and Japan to discover what they learned at school about the contentious Nanjing massacre. Find out what happened on page 38.

Omar Mohammed, aka Mosul Eye, writes on page 47 about his mission to retain information about Iraq’s history, despite risk to his life, while Isis set out to destroy historical icons.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor of Index on Censorship. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on The Abuse of History.

Index on Censorship’s spring 2018 issue, The Abuse of History, focuses on how history is being manipulated or censored by governments and other powers.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89164″ img_size=”213×287″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229108535157″][vc_custom_heading text=”Brave new words” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229108535157|||”][vc_column_text]2010

In 2010, Maureen Freely wrote a piece called Secret Histories for this magazine, about Turkish laws that had kept most of its citizens in the dark about the killings of a million Armenians in the last years of the Ottoman empire[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”90649″ img_size=”213×287″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064220008536796″][vc_custom_heading text=”Censorship in China” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422013495334|||”][vc_column_text]September 2000

How China attempts to censor, using different methods[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”71995″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229308535477″][vc_custom_heading text=”Taboos” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422013513103|||”][vc_column_text]Winter 2015

We tell the story of a Palestinian teacher who took his students to visit Nazi concentration camps in Poland because he felt they should know about the Holocaust. But not everyone agreed.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The abuse of history” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F04%2Fthe-abuse-of-history%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes a special look at how governments and other powers across the globe are manipulating history for their own ends

With: Simon Callow, David Anderson, Omar Mohammed [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99282″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/04/the-abuse-of-history/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]