Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Nathan Law has been imprisoned, disqualified from political office and forced to seek political asylum in the UK – all for fighting for democratic rights in Hong Kong, his home city. But, in spite of it all, he remains optimistic.

“As an activist I’m not entitled to lose hope,” he tells Index on Censorship. “I still believe that maybe in a decade’s time I can set foot in Hong Kong, when it’s democratic and free.”

Law, 28, fled to London in the summer of 2020 after the passing of the National Security Law, a draconian piece of legislation that criminalises even a whisper of criticism against Beijing’s rule.

Given the chance, what would he tell Communist Party leaders in Beijing?

“I would say, ‘There is no totalitarian regime that can remain forever. All of them will collapse’, and I’d say, ‘That is your fate if you continue to do what you are doing’.”

Law’s face and name are synonymous with the struggles in Hong Kong. Alongside Joshua Wong, Alex Chow and Agnes Chow, he has helped drive the recent protest movement.

The son of a construction worker and a cleaner, he first became interested in democratic values at secondary school when the late writer and human rights defender Liu Xiaobo won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010. Liu was serving his fourth prison sentence in China and was unable to accept the prize in person. An image of an empty chair soon went viral, a stark reminder of how bad human rights were in China.

“I grew up in a family that did not talk about politics, did not talk about social affairs,” Law says. Although he studied in a pro-Beijing school, he was “not heavily brainwashed to believe in the Communist Party”. He adds: “I was apolitical. I was not involved.” But when Liu won the prize, the principal of his school publicly denounced the writer in morning assembly.

“It triggered my curiosity because I thought people getting the Nobel Prize are the ones who are good in their field. So how come such a person – a Chinese [person] – would be criticised in that fashion? It really triggered my curiosity and got me to look into the work that he had been doing. He opened up a gate for me to understand all these concepts.”

That gate first led Law to the Tiananmen Square vigil, held in Hong Kong every year since 1989, and then to him leading the 2014 Umbrella Movement (which later landed him in prison on charges of “unlawful assembly”).

After this, Law became the youngest legislator in Hong Kong’s history, a position from which he was quickly disqualified when he modified his oath of allegiance to China during the swearing-in ceremony in October 2016.

In the same year, he founded Demosistō, a pro-democracy political party, with Agnes Chow and Wong.

But time was up when the National Security Law was passed. Demosistō was disbanded, Law was forced out of Hong Kong and Chow and Wong were jailed, alongside scores of others connected to the democracy movement.

Today, dissent is in a straitjacket in Hong Kong. And yet not all have given up fighting. In Law’s recently published book – Freedom: How We Lose It And How We Fight Back – he writes: “Even during this most bitter of times the spirit of ordinary Hong Kong people continues to shine, even if it must do so in the shadows.”

Law lists the people who refuse to have their prison sentences lessened by agreeing to the charges against them and instead “defend themselves in order to narrate their story at the risk of heavy sentencing”. He lists those who attend court hearings to show support to the defendants, those who write letters to the imprisoned and those who advocate for any policy that might remotely challenge the government.

“The hope lies in these people. Even though we are in the darkest time and change is seemingly impossible, people are still doing things because they feel that it is the right thing to do,” he says.

Law might have an admirable sense of hope, but his is not an easy life. He had to publicly sever ties with his family when he moved to the UK and has been unable to talk to Agnes Chow and Wong, too. He misses the people and he misses the place.

“I always dream about Hong Kong,” he says. “You’re familiar with everything. You don’t have to think. Like when you step into the MTR [the subway]. It’s in your muscles, in your memory. You understand everything. You understand all the slang. The background noise with people’s hectic walk, the hectic talk of Cantonese and bus horns, those noises from the stores and from restaurants. It’s just unique.”

Law has been granted asylum in the UK – a move that angered Beijing, which declared him a criminal suspect. Even though he is thousands of miles from Hong Kong, he still has to look over his shoulder. He takes extra precautions: he never mentions where he lives and he takes detours when he leaves and returns home – measures that have come to define the life of China’s dissidents. He simply doesn’t feel safe “because of how extensive China’s reach can be”.

“We’ve got cases like Navalny; the Russian dissident forced to land in Belarus; we’ve also got a lot of cases of Uyghur activists around the world being arrested or extradited back to China. There are a lot of things that can happen to dissidents. It is not a secret that I am almost at the top of the list of national enemies that China portrays, so things like this could happen,” he says.

“On the other hand, I don’t want any of these fears to hinder my activities and my activism. So I will try to be vigilant to protect myself, but I will also try 100% to promulgate the agenda of the Hong Kong democratic movement.”

One of the ways that he wants to do this is through publishing his book. A blend of personal experience and broader context, Law wants it to appeal to as many people as possible and for these people to “act after reading it”.

“I’m an author, of course, but at the end of the day my essential identity is an activist. By definition, an activist is someone who tries to empower people to act in order to precipitate social changes. I intend to appeal to people to be more aware of their own democratic states,” he says.

As for what we can do to help Hong Kong, Law puts it simply: “Get involved. Pay more attention to Hong Kong and to China. Start to look into campaigns that could help, like boycotting the Olympics, supporting political prisoners or even reading news – just supporting the news agencies who produce these fantastic stories for Hong Kong and for China.

“After that, if you really want to be a campaigner that supports Hong Kong then get organised. Find your local grassroots organisation and be a volunteer and try to explain that to your friends and your neighbours.”

It might be the darkest chapter in Hong Kong’s story, but – to channel Law’s optimism – let’s hope it’s not the last.

Young activist Nathan Law’s election to the Legislative Council in 2016 shattered the myth that the people of Hong Kong did not desire freedom and democracy, he says in an extract from his new book

In August 2016, a month before the election, our team were starting to worry. The polls suggested I had little support in the constituency I was running in. Hong Kong Island is a wealthy and generally conservative district, known for electing prominent members of Hong Kong’s professional and elite class – lawyers, public intellectuals and former government officials. To make things more difficult, my constituency happened to have the highest number of elderly residents. It was also an important ‘super seat’ that would return six places in the legislature by proportional representation, so fifteen parties had fielded candidates.

In August 2016, a month before the election, our team were starting to worry. The polls suggested I had little support in the constituency I was running in. Hong Kong Island is a wealthy and generally conservative district, known for electing prominent members of Hong Kong’s professional and elite class – lawyers, public intellectuals and former government officials. To make things more difficult, my constituency happened to have the highest number of elderly residents. It was also an important ‘super seat’ that would return six places in the legislature by proportional representation, so fifteen parties had fielded candidates.Extracted from Freedom: How We Lose it and How We Fight Back, by Nathan Law, published by Transworld in November 2021

This interview and the extract appeared in the winter issue of Index on Censorship. Click here for more information on this issue

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Today’s raid on the offices of Hong Kong media outlet StandNews and the arrest of six individuals linked to it is a brutal crackdown on media freedom. Those arrested include current acting Chief Editor Patrick Lam, Deputy Editor Ronson Chan, pro-democracy activist and lawyer Margaret Ng, and activist and pop star Denise Ho.

The arrests come one day after Jimmy Lai, former owner of Apple Daily and six former Apple Daily journalists were hit with the new charges of “conspiracy to ‘print, publish, sell, offer for sale, distribute, display and/or reproduce seditious publications.”

They are also within days of Tiananmen Square commemoration statues being removed from Hong Kong’s landscape. Each of these actions alone would represent an attack on fundamental freedoms of expression and the media; combined they are an all-out assault, a terrifying combination that seeks to silence any form of dissent and gut the city of media freedom. StandNews has since announced its closure.

Freedom of the press is guaranteed under Article 27 of Hong Kong’s Basic Law, the constitutional settlement that has governed the city-region since 1997. Clearly Beijing has no intention to honour this article. Please join us in condemning these actions and reminding Beijing of its obligations to Hong Kong.

As always we at Index #StandWithHongKong.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

A former food delivery worker calling himself a “second-generation Captain America” and who would turn up at protests in Hong Kong with the Marvel superhero’s instantly recognisable shield has been convicted for violating the country’s national security law (NSL).

On 11 November, Adam Ma Chun-man was sentenced to five years and nine months for inciting secession by chanting pro-independence slogans in public places between August and November 2020.

Evidence cited by a government prosecutor in the court case against Ma included calls for independence he had made in interviews.

Ma becomes the second person to be found guilty under the law imposed by Beijing in July last year. He has lodged an appeal against the verdict.

The first person sentenced under the NSL was former waiter Tong Ying-kit who was jailed in late July for nine years for terrorist activities and inciting secession. Tong was accused of driving his motorcycle into three riot police on 1 July 2020 while carrying a flag with the protest slogan “Liberate Hong Kong. Revolution of our times.”

The watershed ruling on Tong has profound implications for freedom of expression and judicial independence in Hong Kong.

The “Captain America” case has further fuelled fears about the rapid erosion of the city’s room for freedom and the strength of the court in upholding civil liberties.

Like the Tong case, the Ma judgement has significant implications for related cases but the ruling has attracted far less attention. The general public reacted with indifference mixed with a feeling of futility and helplessness. It does not bode well for civil rights and liberties in the city.

The significance of the Ma case lies with the judge’s ruling on what constituted incitement.

Ma’s lawyer said Ma had no intention whatsoever of committing a crime, but was just expressing his views. Merely chanting slogans should not be deemed as a violation of the NSL, the lawyer argued. That he urged people to discuss the issue of independence in schools did not necessarily mean the result of the discussions would be a yes to independence. It could be a no.

Importantly, his lawyer argued Ma had merely expressed his personal views without giving thought of how to make it happen through an action plan. Referring to Ma’s slogan “Hong Kong people building an army”, his lawyer said it was just an empty slogan, again, without a plan.

In sentencing, judge Stanley Chan described the case as serious. He rejected the argument by Ma’s lawyer that the level of incitement in his speeches was minimal, saying Ma could turn more people into the next Ma Chun-man.

Put simply, judge Chan said that although the actual impact of Ma’s speeches in inciting others has been minimal, this was insignificant when determining whether his act constituted incitement.

This view is markedly different from the reaction of the media and the public over Ma’s political antics.

Ma had drawn the attention of journalists when he turned up in protests for obvious reasons. But no more. The lone protester neither had a sizable group of followers nor electrified the sentiments of the crowd at the scene.

The heavy sentencing of Ma will worsen the chilling effect of the national security law on freedom of expression. Importantly, it will have serious implications for a list of incitement cases currently in the process of trial.

In a statement on the sentencing, Kyle Ward, Amnesty International’s deputy secretary general said: “In the warped political landscape of post-national security law Hong Kong, peacefully expressing a political stance and trying to get support from others is interpreted as ‘inciting subversion’ and punishable by years in jail.”

With no sign of an easing of the enforcement of the law 16 months after it took effect, the international human rights group decided to shut down its local and regional offices in the city by the end of the year. They said the Beijing-imposed law made it “effectively impossible” to do its work without fear of “serious reprisals” from the Government.

Hong Kong chief executive Carrie Lam responded by saying no organisation should be worried about the national security law if they are operating legally in Hong Kong, adding Hong Kong residents’ freedoms, including that of speech, association and assembly were guaranteed under Article 27 of the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution.

To a lot of Hongkongers, the assurance, which is an integral part of the former British colony’s “one country, two systems” policy, is an empty promise.

The power of the national security law in curtailing freedoms in other aspects of everyday life in Hong Kong has been widely felt.

In October, the legislature rubber-stamped an amendment to the film censorship ordinance, giving powers to the authorities to ban films that are considered as “contrary to the interests of national security.” The phrase, or “red line” in the law, is much broader than the original version, which targeted anything that might “endanger national security.”

Even before the bill was passed, a number of films and documentary films relating to the 2019 protest were not allowed to be shown in public locally. They include the award-winning Inside the Red Brick Wall and Revolution of Our Times, a nominee in the 2021 Taiwan Golden Horse Film Award.

Moves to revive political censorship in film are part of the authorities’ intensified campaign against threats to national security. While targeting political activists, the net has been widened to curb what officials described as “soft confrontation” and “penetration” through films, art and culture and books.

The University of Hong Kong has called for the Pillar of Shame, a sculpture by Danish artist Jens Galschiot, to be removed from the campus, citing concern over the national security law.

On the legislative front, security minister Chris Tang has given clear reminders that more needs to be done to protect national security, pointing to crimes in Basic Law Article 23 that have not been covered in the national security law.

He has vowed to target spying activities and to plug loopholes following the social unrest in 2019. Tang cited the example that helmets and free MTR tickets were distributed free to protesters during the protests, claiming there were state-level organising behaviours, potentially by actors from outside the country.

Both the central and Hong Kong authorities have labelled the movement as a “colour revolution” with hostile foreign forces behind it, without giving concrete evidence.

In addition to spying, a bill on Article 23 will also cover theft of state secrets and links with foreign organisations. Officials gave no timetable. But it is expected to be at the top of the agenda for the new legislature, which is due to be formed after an election is held on 19 December.

Officials are also looking at introducing a law on “fake news” to eliminate what they deem as lies and disinformation, which went viral on social media during the 2019 protest. The Government and the Police claimed they were major victims of this false information.

Looking back to mid-2020 when the idea of a national security law was first mooted, officials assured Hongkongers the law would only “target a very small number of people”.

Nothing can be further from the truth.

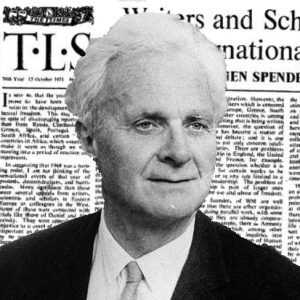

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] On 15 October 1971, in the depths of the Cold War, the feted British poet Stephen Spender wrote an impassioned appeal for the Times Literary Supplement in which he highlighted the threat of a world without creativity or impartial news as repressive regimes sought to silence dissent.

On 15 October 1971, in the depths of the Cold War, the feted British poet Stephen Spender wrote an impassioned appeal for the Times Literary Supplement in which he highlighted the threat of a world without creativity or impartial news as repressive regimes sought to silence dissent.

Writers, academics, journalists and artists were subject to state sanctioned persecution on a daily basis, threatened, arrested and in too many cases murdered as authoritarian leaders moved against their citizens. Watching was no longer enough, letters to the Times and statements of solidarity were no longer sufficient for Spender and a group of his contemporaries.

It was time to act, to provide an international platform for dissidents to publish their work and importantly it was time to make a positive argument for the liberal democratic values of free speech and free expression. It was time to launch Writers and Scholars International and its in-house journal Index on Censorship.

Spender concluded: “The problem of censorship is part of larger ones about the use and abuse of freedom.”

In the 50 years since Spender wrote in the TLS, Index has published the works of thousands of dissidents, their words, their art and their journalistic endeavours. From Havel to Rushdie, from Zaghari-Radcliffe to Ma Jian, their works have found a home in our publication. Their stories have been told and their works published for posterity – a recognition of their plight.

Fifty years later Spender would have hoped for us to be irrelevant, that the fundamental freedom of free expression was not just respected but embraced throughout the world. If only that was the case. Every week there is an attack on academic freedom at home or abroad, a new debate about our online rights and a new report of a systematic attack on those that embody the very principle of free speech.

In 1971 over a third of the world’s population lived under Communist rule with still more living under other forms of totalitarian regime. Today 113 countries, representing 75 per cent of the global population, completely or significantly restrict core human rights.

These aren’t just statistics, there are real people behind each headline.

In Belarus 811 people are currently detained as political prisoners by Lukashenka, including Andrei Aliaksandrau one of Index’s former staff members. In Egypt more than 60,000 people are imprisoned, including our award-winner Abdelrahman Tarek – detained and regularly tortured since the age of 16 for attending democracy demonstrations. In Afghanistan three young female journalists were brutally assassinated as they left work earlier this year. In Hong Kong the 50 leading democracy protestors have been arrested by the CCP and their families threatened.

These brave journalists and campaigners represent millions of people who cannot use their voices without fear of retribution. Every day they face a horrendous choice between demanding democratic rights or being silenced.

Index seeks to be a platform for them – providing a voice for the persecuted, ensuring that no tyrant succeeds in silencing dissent.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also wish to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]