Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

16 August, 2016 – IMC TV reporter Gulfem Karatas and cameraman Gokhan Cetin were assaulted and detained while covering the police raid on the daily Ozgur Gundem. Footage of the attack was shared via IMC TV Twitter account, showing police grabbing the camera and physically assaulting the reporter, who is heard screaming in the footage.

Karatas and Cetin were detained along with journalists Günay Aslan, Reyhan Hacıoğlu, Ender Öndeş, Doğan Güzel, Ersin Çaksu, Kemal Bozkurt, Sinan Balık, Önder Elaldı, Davut Uçar, Zana Kaya, Fırat Yeşilçınar and Mesut Karnak.

In an official statement IMC TV said: “During the live broadcast, the police prevented Gulfem Karatas and Gokhan Cetin from reporting and detained them violently along with at least 21 Ozgur Gundem employees. We condemn this unacceptable treatment to our colleagues who were on duty and ask for their immediate release.”

16 August, 2016 – Journalist Vladimir Zivanovic and photographer Boris Mirko, who work for the daily Serbian Telegraph were threatened and insulted while reporting on the illegal construction of an aqua park in the capital Belgrade.

The journalists were in an area of the city where former professional football player Nikola Mijailovic is building the controversial aqua park. Mijailovic approached the journalists and shouted a series of insults about them and their families. He reportedly told them that they should be put in a gas chamber together.

Mijailovic also reportedly tried to bribe them. The journalists have reported the threats to the police and Serbia’s Independent Association of Journalists has condemned the incident.

15 August, 2016 – A court in Baku ruled to uphold a travel ban against investigative reporter Khadija Ismayilova. “Binagadi Court told me because I have no husband, kids or property, I might not be able to return if I leave the country,” Ismayilova said following the hearing in Baku.

Ismayilova was released from prison on 25 May on a suspended three-and-a-half-year sentence.

Also read: Azerbaijan’s long assault on media freedom

16 August, 2016 – The eighth administrative court in Istanbul ordered the closure of the newspaper Ozgur Gundem on the grounds of “producing terrorist propaganda”.

The court order described the closure as “temporary” although no duration appears to be specified in the text of the decision.

Later that day, Ozgur Gundem’s offices were raided by the police.

According to P24, the 23 members of staff were taken into custody. They are: Editor-in-Chief Zana Kaya, journalists Zana Kaya, Günay Aksoy, Kemal Bozkurt, Reyhan Hacıoğlu, Önder Elaldı, Ender Önder, Sinan Balık, Fırat Yeşilçınar, İnan Kızılkaya, Özgür Paksoy (DİHA news agency) , Zeki Erden, Elif Aydoğmuş, Bilir Kaya, Ersin Çaksu, Mesut Kaynar (DİHA), Sevdiye Gürbüz, Amine Demirkıran, Baryram Balcı, Burcu Özkaya, Yılmaz Bozkurt (member of the press office of the Istanbu Medical Chamber), Gülfem Karataş (İMC), Gökhan Çetin (İMC) and Hüseyin Gündüz (Doğu Publishing House).

Also read: Turkey’s continuing crackdown on the press must end

11 August, 2016 – Dmitri Remisov, the Rostov-on-Don regional correspondent for Rosbalt news agency, told the agency that he was repeatedly assaulted by police officers while being questioned at the regional Center for Counteracting Extremism.

According to Remisov, he was asked to come to the CCE to answer questions related to a criminal case “on the preparation of a terrorist act” in Rostov, a city in south-west Russia.

He reported that two police officers asked him whether he knew certain individuals, where most of the people he was asked about were opposition activists.

“Then they asked me if I knew a certain Smyshlayev. I said that I didn’t remember such a person,” Remizov said.“One officer started saying I did know this person in 2009, after which he struck my head three times. Afterwards, he began threatening me, saying he could prosecute me under the criminal law or could have some Nazis punish me.”

After he was questioned another policeman threatened him with physical punishment, saying “we will meet [with you] once again”.

The Rosbalt correspondent received medical care after the questioning. He also filed a complaint against police officers, Rosbalt reported.

Mapping Media Freedom

|

44 journalists are in Turkey’s jails tonight. We demand their release. Because we, too, are journalists, and… pic.twitter.com/jzDsd9MOqm

— P24 (@P24Punto24) July 11, 2016

The above was part of a series of tweets were sent out by Platform for Independent Journalism (P24) near midnight on 11 July. P24 joined editors, reporters, columnists, bloggers and civil society activists, who are, despite being a minority in the shackled media sector in Turkey, determined to defend the honour of our noble profession till the very end.

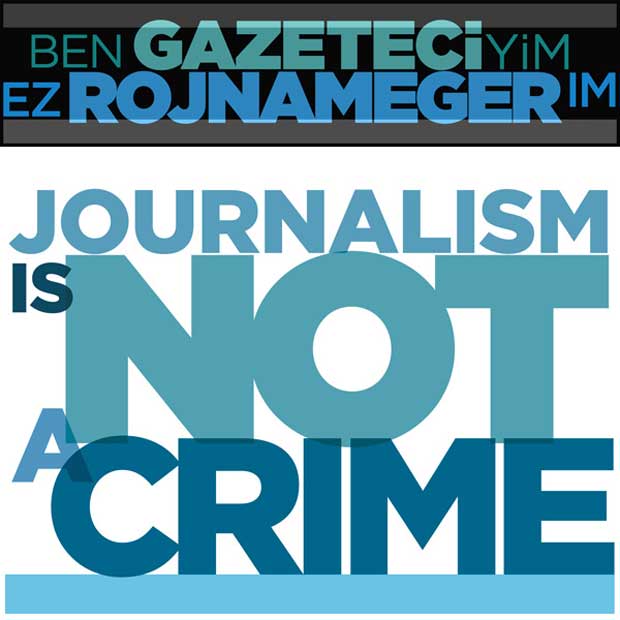

The “Journalism is not a crime” logo is now in circulation in Turkish, Kurdish, English and a variety of other languages. The hope is that this slogan will trigger widespread domestic and international solidarity to rescue Turkey’s journalism from being turned into a total wreck.

On Tuesday morning, I watched three of the figures behind the campaign on TV. It is a rarity, these days, that any voice in defence of freedoms and rights find a public space on Turkey’s TV stations. It filled me with a sense of pride, hope and courage, but was tinged with a slight sense of despair.

That any so-called private mainstream TV channel would invite them on to share their views is a daredevil act, because these newsrooms are practically run by the same proprietors and their puppet editors, whose variety of businesses are strictly dependent on the public contracts, and any challenge to the AKP government would mean severe punishment. This is the impact self-censorship, in addition to direct censorship, has had on public debate as well as free reporting in roughly 90% of the Turkish media.

The appearance of Fehim Işık, a Kurdish columnist, Said Sefa, owner of the independent news site Haberdar, and Arzu Demir, a leading figure in the Turkish Journalists’ Union on the tiny Can Erzincan TV took place with an air of gloom. One of the three or four channels still willing to broadcast critical and diverse content, this channel will be dropped fromTurksat satellite by 20 July, on the back of a murky decision by the satellite board over claims it spreads terrorist propaganda.

Experienced lawyers are flabbergasted once more by the lawlessness reigning over the media domain, but there is little they can do about it. A month or so ago, another TV channel, IMC TV, met the same fate and was forced to switch to a different satellite service, losing more than 75% of its mainly Kurdish audience. Can Erzincan TV, a financially strapped and tiny liberal outlet, will also lose viewers. This is a cunning form of censorship by the authorities.

With Can Erzincan TV pushed out of the limelight, Turkish viewers will be left only with Halk TV and FoxTV, both of which are also in the crosshairs for further punitive actions.

When – rather than if – they also are gone, the AKP will have a free ride on the most powerful, efficient medium in journalism. Remnant portions of dignified journalists, regardless of their political colour, will have to retreat into a handful newspapers and news sites.

This is the bad news.

The good news is that, as I expected, the very core of real journalism in Turkey is intent on professional resistance to further erosion. The current initiative #Iamajournalist is yet another amazing attempt to rise up. I watched it develop spontaneously as a social media movement, which rapidly turned into a community action.

The very good news is that it now contains elements which find common cause between the liberals, leftists, Kurds, seculars, and concerned conservatives: protecting journalism as the main pillar of democracy. This is unfinished business in Turkey, and something the country’s “dark forces” want to reverse in full.

For a week starting from July 11, a handful of newspapers, websites and TV channels will display the “Journalism is not a crime” logo. Social media, too, is busy.

“Protecting freedom of press also means defending the public’s right of access to information. In a society where the right to information is restricted, one cannot speak of democracy,” they say.

“As journalists we will do everything within our power to be the voice of those who have been marginalised, imprisoned, and silenced for doing their jobs and defending the freedom of press and freedom of access to information for all of us.”

We must now keep in our minds the 44 journalists in Turkish jails. It’s a grim number that will rise. There are thousands of journalists who are forced to operate in newsrooms resembling labor camps, or — to use a term I used in my Harvard paper a year and a half ago – “open-air prisons”, subordinated to spread propaganda, lies and hate speech.

This spontaneous initiative, which grew without the involvement of some polarised journalist organisations, needs attention, and support. Journalists in Turkey are tough nuts, but the conditions are swiftly hardening. We need to keep the spirit of journalism alive.

Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, during a state visit to Ecuador in February 2016. (Photo: Cancillería del Ecuador via flickr)

Nothing could illustrate the course of developments in Turkey better than the case of prosecutor Murat Aydın.

In what was described as a “judicial coup” in critical media, Aydin was one of 3,746 judges and prosecutors, who were reassigned in recent days, an unprecedented move that has shaken the basis of the justice system. Some were demoted by being sent into internal “exile”, some were promoted.

According to daily Cumhuriyet, his pro-freedom stance landed him in the former group.

Aydin’s transgression was to challenge the Turkish Penal Code’s Article 299 — the basis of “insulting the president” cases — in the country’s constitutional court. He argued that Article 299 was unconstitutional and conflicted with the European Convention on Human Rights. He had asked the top court to void the article.

After the reshuffle, he was told he would now be handling cases in Trabzon on the Black Sea coast, clear across the country from İzmir on the Aegean, where he had been working.

“I was exiled because of the decisions I have made and my expressed views,” he told Cumhuriyet. ”The worst part is, there is no authority any longer where we seek these type of sanctions to be checked, where we can challenge unjust acts.”

Meanwhile, another prosecutor, Cevat İslek, who made his name filing charges against journalists on the basis of “insulting the president” was promoted, Cumhuriyet noted, to the position as the deputy chief prosecutor in Ankara.

One wonders how such transfers are perceived by the public. Do Turks notice that the how the president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and his AKP government are seizing control over the domain of expression through the imposition of large-scale punitive measures? Do they notice that this is taking place in defiance of the constitution, which defines the office of the president as being “impartial”?

The accelerated authoritarianism in Turkey — chiefly targeting media, academia and civil dissent — leaves nothing to chance. Though the media sector and its professionals remain top of the list for the president’s persecution, those who are seen as instrumental in filing and judging the court cases against them are also targets.

The issue has raised the alarm levels to new heights. In a recent report a global body of legal experts issued an “orange level” of concern on the state of the judiciary in Turkey, warning, after scrutinising the rising problems, that it is falling into total subordination of the executive.

”The ICJ remains concerned that transfers are being applied as a hidden form of disciplinary sanction and as a means to marginalize judges and prosecutors seen as unsupportive of government interests or objectives,” the Geneva-based International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) wrote in its report, Turkey: the Judicial System in Peril, which was prepared after a long series of talks with anonymous judges and prosecutors, among others.

“Many of those with whom the mission met noted that there are now unprecedented levels of pressure, division, distrust and fear in the Turkish judiciary. There are alarming signs that this has already led to manipulation of the judicial system on political grounds, including to target government opponents or to criminalize and prosecute criticism of the government. Of particular concern, is the high number of prosecutions for offences restricting freedom of expression, in particular for the offence of ‘insulting the president’.”

With the backbone of justice highly infected by partisanship, a “total eclipse” is looming and it becomes much easier to grasp the magnitude of oppression. “Insulting” cases may have risen above 2,000 since last year, but what is happening today is a multifaceted assault on freedom of speech and journalism as a whole.

Media monitoring organisations – Platform for Independent Journalism, Reporters Without Borders and Turkish Trade Union of Journalists – estimate that, now, the portion of media under direct and/or indirect control of the presidential palace and the AKP, is around 90%. This is corroborated by Mapping Media Freedom, which has recorded the litany of cuts against journalism.

The remnant segment of independent journalism operates, under great legal and financial strain, with dailies such as secular Cumhuriyet, liberal Özgür Düşünce, leftist Birgün and Evrensel, and Kurdish Özgür Gündem. On the TV side, the “capture” is even more severe: there are only three channels — Kurdish IMC TV, liberal CanErzincan and secular Halk TV — airing critical content.

But even such a weakened media segment seems to worry the authorities. The most recent meeting of the National Security Council, a powerful body symbolising state authority, ended with the endorsement that the battle against what the AKP sees as the “domestic enemies”, namely the Kurdish Political Movement and what Erdoğan depicts as “parallel structure” Gülenists, will be escalated.

Everybody knows what this refreshed announcement means: the remaining independent outlets will be criminalised by any means necessary. The latest developments indicate that the special office of prosecution on crimes against the constitution is preparing to launch inquiries against a number of outlets, chiefly targeting the Kurdish media. In other words, further closures may be expected to appear on the government’s agenda.

Along with the systematic arrests of more than 12 reporters of Dicle News Agency, which is almost the only source of news on what takes place during “scorched earth” operations in the mainly Kurdish southeastern provinces, the strongest sign on the media clampdown is the legal investigation filed against more than 15 well-known journalists — most of them non-Kurdish — who took part in an act of solidarity, “Chief Editors Vigil”, with the pro-Kurdish daily, Özgür Gündem.

The journalists are expected to be charged with “terrorist propaganda” under Turkey’s anti-terror law, which Erdoğan and the AKP government refuses to revise despite EU demands – a key criteria for visa liberalisation for Turkish citizens.

Nothing, it seems, will suffice to alter the authoritarian course Turkey has been taking and the price journalists and peaceful dissidents are forced to pay rises geometrically.

But nothing seems to stop the tiny-but-tough core of resistant journalists who continue to confront the Orwellian state as it consolidates itself under the nose of the pro-government and subservient media.

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are just five reports from 23-29 February that give us cause for concern.

#Russia journalist Sergey Vinokurov assaulted outside editorial offices https://t.co/5bP5oxAfMc @IndexCensorship

— CoE Media Freedom (@CoEMediaFreedom) March 2, 2016

The physical safety of journalists in Russia remains a major concern. Sergey Vinokurov, a correspondent for the weekly politics and news magazine Sobesednik, was assaulted outside the publication’s offices in Moscow on 25 February at around 9.20pm. As Vinokurov left for home, a perpetrator hit the journalist multiple times in the body and face, just ten meters from the entrance. The assailant, who appeared drunk, shouted vulgarities and said: “you’re getting this for your articles”. Vinokurov tried to dodge the punches and managed to make his way back to the entrance to the building’s entrance, but the assailant followed and continued his assault.

Security guards and other journalists were able to restrain the perpetrator before police arrived and brought the assailant to a detention center at the Tverskoi police department. Police have opened an investigation. The attacker was a 37-year-old Anton M, who lives next to the editorial office.

The French Minister of Defence, Jean-Yve Le Drian, launched an investigation into French newspaper Le Monde on 24 February for “compromising the secrecy of national defence” following the publication of an article on the on the presence of French special forces in Libya. The article reported: “Highly targeted pinpoint strikes, prepared by discreet or covert actions: in Libya, this is the course of action taken by France against the threat of the Islamic State.”

Under French law, compromising the secrecy of national defence is punishable by a €45,000 fine and a 3-year prison sentence. The Le Monde claims that “specialised bloggers” had spotted the presence of French security forces in eastern Libya since mid-February.

Spring arrives in #Idomeni, where thousands of migrants remain stranded https://t.co/8n0PVfb4KV#Greece #FYROM pic.twitter.com/xuAOrpUeB2

— YouTube Newswire (@ytnewswire) March 2, 2016

It’s been almost a year since phrases “migrant crisis” and “refugee crisis” started making headlines, and in that time we’ve seen many European governments making it increasingly difficult for asylum seekers to cross into their territorial boundaries. Most recently, Macedonia tightened its border control, leaving about 4,000 people stranded in Greece. The Greek government responded by removing refugees from a camp in the border town of Idomeni, putting them on buses bound for Athens, where they were to be temporarily housed in relocation camps.

While trying to cover events at the border, a TV crew for private broadcaster Alpha Channel was denied access. Greek police asked journalist Aphroditi Spilioti, a cameraman and a sound engineer to leave the camp “safety reasons”. The TV crew then moved outside the perimeter of the camp, where they could still observe the ongoing police operation, but again they were asked by police to move — this time 2 km away — for “safety reasons”.

When the journalist and the crew refused to do so, they were asked to provide their ID cards for verification and follow the police vehicle to the station. The police also reportedly told them not to drive back to the refugee camp.

Former president of the province of Valencia, Francisco Camps, tried to convince radio journalist for Cadena SER, Miguel Ángel Campos, to reveal his source when the journalist called to ask the politician about alleged corruption on 29 February.

Camps, who was filming the phone conversation, told the journalist: “I have to know who I need to talk to in order to not have a big mess tomorrow. […] I am asking you a favour, please, tell me what source told you that I was collecting money. I need to talk to that person and to defend myself.”

The journalist still refused to reveal the identity of his source. The politician continued to deny the allegations and asked to involve the journalist’s boss: “Please call him right now and tell him that you talked to me. And please tell him not to talk or to do something because all of this is a lie. Please, this is really important, talk to your boss, and if he would like to talk to me I am available.”

Imc TV cuts off after suspension order! #imcTvSusturulamaz Seriously… What does the future hold? #Turkey pic.twitter.com/HalVpj63ZC

— Cagil M. Kasapoglu (@CagilKasapoglu) February 26, 2016

The independent Turkish broadcaster IMC TV was pulled off the air by one of Turkey’s largest broadcasters, Turksat, on 26 February following terror charges. Ankara prosecutor requested IMC be taken down because of allegations that the channel is “spreading terrorist propaganda” for the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which Turkey has designated a terrorist organisation.

The channel was taken off the air during a live interview with Can Dundar and Erdem Gul, two prominent journalists who were freed pending trial that same day after spending 92 days in prison. Index on Censorship has condemned the decision. Senior Advocacy Officer Melody Patry said: “Turkey must halt its crackdown on media outlets and ensure citizens have access to diverse information and viewpoints, including those that differ from the government’s political line.”

This article was originally published on Index on Censorship.

Mapping Media Freedom

|