Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

As NATO bombs were falling on the Serbian capital Belgrade on 11 April 1999 , a man was being executed on a side street in the centre of the city. The victim was later identified as Slavko Curuvija, a prominent Serbian anti-regime journalist. A post mortem found that Curuvija had been shot in the back 17 times. Five days earlier the state-run daily Politika Ekspres had published an article calling Curuvija a traitor and a NATO supporter.

Fast forward to 1 June 2015: the trial of four former security officers begins before a special court in Belgrade. It took 16 years for anyone to stand trial over what had become a notorious case of intimidation of journalists in Serbia.

Much of the credit for pursuing a cause by many considered lost can go to veteran journalist Veran Matic, the editor-in-chief of media group B92.

Several Serbian governments had shown no signs that they were willing to solve Curuvija’s case; the same goes for many other war-time murders. For years, Matic and his fellow journalists would mark the anniversary of Curuvija’s death by laying flowers at Svetogorska Street, where he lived and died, and by raising awareness in the media and with the government. It was not enough.

In 2013, Matic was fed up with waiting for answers about the murders of his colleagues. He proposed to form a special body to investigate the killings of Curuvija and two other journalists. Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic — then deputy prime minister — gave Matic permission to form the Commission for Investigating Killings of Journalists in Serbia. It was an unexpected move. As Curuvija was being executed on a Belgrade side street, Vucic was minister of information in President Slobodan Milosevic’s government.

“Some criticised the establishment of the commission for giving an opportunity to Vucic to clear his past,” says Matic, referring to the unease many journalists felt towards Vucic, who was highly critical towards independent media during the nineties.

“Marking every year the anniversary of the killing, visiting the place of assault, criticising the state again and again for failing to resolve those crimes became very humiliating for me,” Matic said. “In this way, I have been given another instrument through which I could do something in practice.”

It was clear that Matic needed the government’s cooperation if he wanted the murders to be solved. “I wanted to get hold of every single document and, in order to do this, we needed a commission that would be supported by the government,” he said. But Matic managed to ensure the body was made up of three representatives of the independent media, three members of the ministry of internal affairs and three representatives of the security information agency. With Matic himself serving as the commission’s chairman, journalists will always be in the majority.

Progress and challenges

The commission is focusing on three big murder cases from the recent past. The work around Curuvija’s case has been the most successful until now, with four people charged. Trials for former Chief of State Security Rade Markovic and the two ex-secret service officers Ratko Romic and Milan Radonjic began 1 June. The fourth accused is Miroslav Kurak, also a former state security member and the man who is believed to have pulled the trigger on Curuvija. He is being tried in absentia, as he is still at large, an Interpol warrant issued for his arrest. There are clues that Kurak is living in Central or South Africa where he owns a hunting safari agency.

The Dada Vujasinovic case is perhaps the most difficult, as the murder took place over two decades ago. Vujasinovic was a reporter for the news magazine Duga and wrote about Zeljko Raznatovic, also known as Arkan. She was found dead in her apartment in 1994. The police ruled it a suicide, but most evidence disputes this. When the commission started working on the case, there were doubts about the forensic research done in Serbia at the time. “I decided that the first step would be to seek expertise outside of the country, as the trust in domestic institutions had been compromised,” said Matic. “We asked the Dutch National Forensic Institute based in The Hague, who offered to perform the forensic examinations for 35,000 euro. We are now raising funds for this, given that the prosecutor’s office has no budget for these services.”

The third case is that of Milan Pantic, who was murdered in June 2001 while entering his apartment building in the central Serbian town of Jagodina. Attackers broke his neck, and was also struck on the head with a sharp object. Pantic worked for the newspaper Vecernje Novosti, where he reported on criminal affairs and corruption in local companies. Prior to the killing, he had received numerous telephone threats in response to articles he had written. It’s not an easy task to investigate. “We know that one of the suspects is living in Germany under a different name,” explained Matic. “But we didn’t get permission to conduct an interview with him.”

The commission is also looking into the deaths of 16 media staffers from RTS — Serbia’s state broadcaster — who were killed during a NATO airstrike targeting its headquarters in 1999. “This is a very complex issue,” said Matic. “The executioner is certainly a pilot of one of the NATO member countries. The people who decided to put a media company on the list of war targets should face trial, as well as those who issued the order to launch missiles and kill the media workers. And also the people responsible in Serbia, who knew the building would be bombed and did not evacuate it.” NATO is refusing to cooperate in this case.

Unique commission

It is of great importance, Matic believes, that these cold cases will be solved. “Unpunished crimes, especially this committed by state institutions, only call for new violence, threats and endangerment of the safety of journalists. It leaves deep scars in the lives of journalists in this country and it contributes to censorship and fear.”

A commission like this is unique in the world; a government body controlled by independent media representatives. And its first success, the arrests in the Curuvija murder case, was surprising to many who’d lost faith in the justice system in Serbia. “This commission was not established by politicians. On the contrary, they accepted all my requests and ideas,” said Matic. “This is quite an atypical commission that works on making results, and none of its members have any political or other motives, but solely finding the killers and masterminds that hide behind the killings, and bringing them to justice.”

Jailing the head of Serbia’s secret service during the nineties, a dark period for both the country and its internal security apparatus, has come with a high price. Matic now lives under 24/7 police protection and he can’t travel anywhere without a police escort. “Some names have again been brought to light, along with their disgraceful role [in the killings]. Some are threatened with arrest, while some of them have been arrested already,” he said of the ongoing investigation.

Matic receives threats often, mostly via email, some of them to his life. But he has gotten used to having police officers in front of his door at all times because, he said, the truth is worth the compromise.

“This is the price we have to pay in order to resolve those crimes,” he said. “It will contribute to the catharsis of our society.”

Mapping Media Freedom

|

An earlier version of this article stated that Aleksandar Vucic was interior minister when the commission was set up. This has been corrected.

This article was posted on 16 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

“Impunity is a great threat to press freedom in Russia,” said Melody Patry, Index on Censorship’s Senior Advocacy Officer. “Failing to use appropriate measures to investigate the murder of Akhmednabi Akhmednabiyev is not only a denial of justice, it sends the tacit message that you can get away with killing journalists. When perpetrators are not held to account, it encourages further violence towards media professionals.”

Statement

On the 2nd anniversary of the murder of independent Russian journalist, Akhmednabi Akhmednabiyev, we, the undersigned organisations, call for the investigation into his case to be urgently raised to the federal level.

Akhmednabiyev, deputy editor of independent newspaper Novoye Delo, and a reporter for online news portal Caucasian Knot, was shot dead on 9 July 2013 as he left for work in Makhachkala, Dagestan. He had actively reported on human rights violations against Muslims by the police and Russian army.

Two years after his killing, neither the perpetrators nor instigators have been brought to justice. The investigation, led by the local Dagestani Investigative Committee, has been repeatedly suspended for long periods over the last year and half, with little apparent progress being made.

Prior to his murder, Akhmednabiyev was subject to numerous death threats including an assassination attempt in January 2013, the circumstances of which mirrored his eventual murder. Dagestani police wrongly logged the assassination attempt as property damage, and only reclassified it after the journalist’s death, demonstrating a shameful failure to investigate the motive behind the attack and prevent further attacks, despite a request from Akhmednabiyev for protection.

Russia’s failure to address these threats is a breach of the state’s “positive obligation” to protect an individual’s freedom of expression against attacks, as defined by European Court of Human Rights case law (Dink v. Turkey). Furthermore, at a United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) session in September 2014, member States, including Russia, adopted a resolution (A/HRC/27/L.7) on safety of journalists and ending impunity. States are now required to take a number of measures aimed at ending impunity for violence against journalists, including “ensuring impartial, speedy, thorough, independent and effective investigations, which seek to bring to justice the masterminds behind attacks”.

Russia must act on its human rights commitments and address the lack of progress in Akhmednabiyev’s case by removing it from the hands of local investigators, and prioritising it at a federal level. More needs to be done in order to ensure impartial, independent and effective investigation.

On 2 November 2014, 31 non-governmental organisations from Russia, across Europe as well as international, wrote to Aleksandr Bastrykin calling upon him as the Head of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation, to raise Akhmednabiyev’s case from the regional level to the federal level, in order to ensure an impartial, independent and effective investigation. Specifically, the letter requested that he appoint the Office for the investigation of particularly important cases involving crimes against persons and public safety, under the Central Investigative Department of the Russian Federation’s Investigative Committee to continue the investigation.

To date, there has been no official response to this appeal. The Federal Investigative Committee’s public inactivity on this case contradicts a promise made by President Putin in October 2014, to draw investigators’ attention to the cases of murdered journalists in Dagestan.

As well as ensuring impunity for his murder, such inaction sets a terrible precedent for future investigations into attacks on journalists in Russia, and poses a serious threat to freedom of expression.

We urge the Federal Investigation Committee to remedy this situation by expediting Akhmednabiyev’s case to the Federal level as a matter of urgency. This would demonstrate a clear willingness, by the Russian authorities, to investigate this crime in a thorough, impartial and effective manner.

Supported by

ARTICLE 19

Albanian Media Institute

Analytical Center for Interethnic Cooperation and Consultations (Georgia)

Association of Independent Electronic Media (Serbia)

The Barys Zvozskau Belarusian Human Rights House

Belorussian Helsinki Committee

Center for Civil Liberties (Ukraine)

Civil Society and Freedom of Speech Initiative Center for the Caucasus

Crude Accountability

Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly – Vanadzor (Armenia)

Helsinki Committee of Armenia

Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights

The Human Rights Center of Azerbaijan

Human Rights House Foundation

Human Rights Monitoring Institute

Human Rights Movement “Bir Duino-Kyrgyzstan”

Index on Censorship

International Partnership for Human Rights

International Press Institute

Kharkiv Regional Foundation -Public Alternative (Ukraine)

Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law

Moscow Helsinki Group

Norwegian Helsinki Committee

PEN International

Promo LEX Moldova

Public Verdict (Russia)

Reporters without Borders

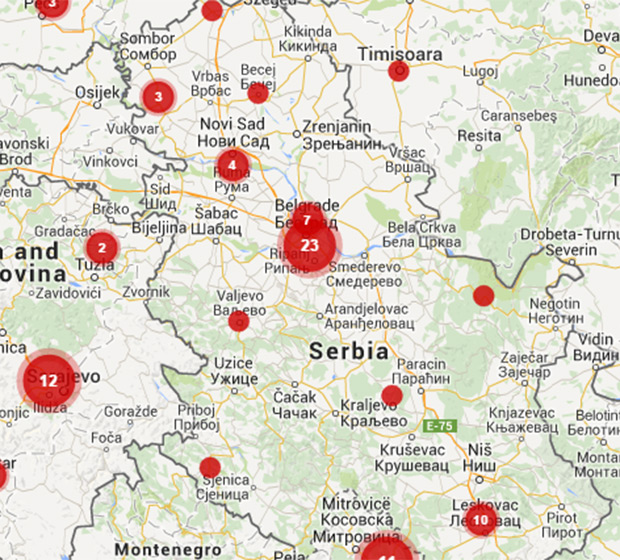

There have been 48 reported violations of media freedom in Serbia since May 2014.

Around 1 am on Thursday 3 July 2014, Davor Pasalic, editor of Serbian news agency FoNet, was brutally assaulted as he made his way home from the office. Pasalic, who had stopped for pizza, was accosted by three young men who demanded money and told him they had a gun. Pasalic refused and the men began beating him while shouting nationality-based slurs. Pasalic estimates that they struck him about 30 times before leaving him alone. The injured man then crossed a bridge leading to his apartment and was again attacked by the three men. The two attacks left him with cuts and bruises to his head and body. Four of his teeth were broken or knocked out.

“I have no clue why those three guys attacked me,” Pasalic told Index on Censorship. “One of the guys asked me: Are you a Croat? I was born in Belgrade. I have no accent. I look like every other citizen of Belgrade. Nobody has ever asked me that question before. How did he figure out that I am ethnic Croat?”

Six months have elapsed since the brutal assault, but police have made no progress in unmasking the culprits or discovering their motives. Nebojsa Stefanovic, Serbian minister of internal affairs, insists authorities are handling the incident as a priority, while Pasalic has said he is not certain whether police are unwilling or unable to resolve the assault. Journalists’ associations in Serbia are worried, vowing they “won’t allow” the beating to become just another case in the long line of unresolved attacks on media workers in Serbia.

From 2008 to 2014, Serbian has seen a total of 365 physical and verbal assaults, intimidations and attacks on property of media professionals, according to a report by the Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia (NUNS). The numbers should be taken as provisional, it added, since many media workers do not report attacks. The real figure is likely higher than the official one. Since May 2014 alone, Index’s European Union-funded Mapping Media Freedom has received 48 reports of violations against Serbian media including attacks to property and intimidation and physical violence, one of which was the attack on Pasalic.

“In the period between 2008 and 2011 less than 10 per cent of all attacks were processed,” NUNS said. “We also have problems with the judicial process, even in cases where the identity of the aggressor is very obvious. In Serbian courts it is common for attackers to receive minimum sentences, which obviously encourages attacks,” said NUNS’ President Vukasin Obradovic in a statement. He believes this situation leads to self-censorship within the country’s press.

Media freedom violations are also covered in the annual reports on human rights in Serbia by the Belgrade Center for Human Rights (BCHR). In 2013 they reported, among other things, that hand grenades had been thrown at the home of the owner of the website Telegraf and that four journalists were under 24 hour police protection. In 2012 they pointed out, pointed out that despite a high number of attacks on the media, trials of press workers progressed faster than trials of perpetrators of attacks on journalists: “Minister Velimir Ilic was at long last found guilty and fined almost 1.4 million RSD for physically assaulting a journalist of the Novi Sad TV Apolo back in 2003. The assailant on TV B92 cameraman in 2008 was sentenced to one year in jail in 2012. The men who threatened to kill the author of the B92 show Insider Brankica Stankovic in 2009 were sentenced to 16 months’ imprisonment and six-month and one-year conditional sentences respectively.”

BCHR noted in its 2011 report that some court judgments confirmed the suspicion that perpetrators who attack journalists can count on lenient sentences. In 2010, they found that journalists were mostly being attacked by politicians, policemen and local businessmen dissatisfied with their reporting, and that — like in the previous years — most of the perpetrators went unpunished.

There are also cases where law enforcement authorities appear to simply not be doing their jobs, according to lawyer Kruna Savovic, who is part of the NUNS legal team. Speaking to Radio Free Europe, she shared the story of a journalist who reported death threats against him and his mother to the police. He stated the identity of the suspect, named witnesses and filed a report, but instead of processing the case, officers told him he would be charged if he continued to bother them.

The attacks on Pasalic were not captured by surveillance cameras in the area, and according to Stefanovic’s statement, the lack of video is complicating the investigation. The minister also asserted that a report was not filed on the night of the incident. Pasalic refutes that, saying he had sought medical treatment at the military medical academy after the assaults and told the on-duty officers what had occurred.

Serbian journalists’ associations have been unified in condemning the incident. “Serbian society is burdened with numerous attacks on journalists which remain unsolved and their perpetrators unpunished, sometimes for decades. This encourages the attackers and contributes to spreading fear and insecurity both among journalists and the society as a whole,” the Association of Independent Electronic Media (ANEM) pointed out.

The international community has also taken note. “Journalists’ safety is a key issue in the OSCE region. There must be no impunity for crimes committed against media workers”, said OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatovic, and in its 2014 progress report on Serbia, the European Commission stressed that threats and violence against journalists “still remain a concern”. The Commission and other international non-governmental organisations urged Serbian authorities to keep their promised to investigate the killings of journalists Radislava Dada Vulasinovic in 1994, Slavko Curuvija in 1999 and Milan Pantic in 2001, as well as other attacks.

So far a Serbian special commission, which was created in 2013 and tasked with reopening the unresolved murders of journalists has achieved progress in the case of Curuvija. The commission found information that connects four former state security officials with the killing. They were all charged. Three of them were imprisoned while “one of the indicted men is believed to be on the run and living in an African country”. In 2014, NUNS reported, there was only one journalist under 24 hour police protection.

After six months of investigation and zero progress Pasalic ironically says that his case is “no big deal.” But, he said that the assault has had no impact on his work.

Veteran B92 journalist Veran Matic has worked against impunity and to bring murders of Vulasinovic, Curuvija and Pantic to justice. “The culture of producing fear is the most efficient form of censorship,” he told Index last November. But he added: “In the same way as impunity restricts freedom of speech, solving of these cases, at least 20 years later, will surely contribute to journalists being encouraged to do their job in the best possible way.”

Recent reports from mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

Serbia: Prime minister calls BIRN’s journalists “liars”

Serbia: Journalist fired after demotion

Serbia: “Doctors” send death threats after report

Serbia: Mayor criticised for implying journalists not welcome

Serbia: Journalist demoted after publishing report

This article was posted on 12 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

Impunity is a festering sore on freedom of the press. Harassment, violence and murder of journalists are problems around the world — even in Europe, as Index’s project mapping media violations has shown. The numbers speak for themselves: of the 370 media workers murdered in connection with their job over the past ten years, 90% have been murdered without their killers being punished. Many of these crimes aren’t even investigated.

Ahead of the International Day to End Impunity, journalists from across the world told Index why impunity is such a danger to free expression and a free press.

Impunity generates corruption and its enemy is the one thing that exposes and threatens it: the freedom of the press.

The HOT DOC is currently facing 40 lawsuits mainly from ministers and politicians in an attempt to shut us down as journalists. We reveal scandals like one with the minister of justice, a former judge who committed an “error” that granted amnesty to officials who had abused public funds, and instead of answering in public as required as politicians, we are being sued. We pester the courts and despite winning lawsuits, we need more than 80,000 euro per year for court expenses.

It is a problem that journalists around the world get threatened, intimidated and killed just for doing their job.

These crimes, like any other crime, need to be investigated. If not, it sends a message that this is okay; that the law is only for certain people. It is an implicit acceptance of this behaviour.

If we want to have a strong press, threats, intimidation and murder of journalists can’t be seen to be implicitly condoned by the state. It’s a dangerous message. It makes people frightened to ask tough questions, and if that happens, you are on the way to shutting down a robust press.

I come from a country where we have a lack of justice. The executive power controls the parliament and the justice system. People feel that if they get mistreated or oppressed by those in power nothing will protect them or bring them justice.

Not only people who express their opinions suffer from a lack of justice. People from different backgrounds who have a different way of thinking and different interests also don’t trust the justice system. Those who have more power can easily avoid punishment and take revenge against victims who tried to get their rights through judiciary system.

Officially, police officers don’t have any kind of formal immunity. According to the law they can be questioned if they violate the rights of people by torturing or murdering. But, in fact, all those accused of killing protesters and torturing prisoners managed to avoid being punished, with a few exceptions.

I feel that it’s not safe to express your opinions freely in a country where people can easily avoid punishment.

I have been sentenced to four years in jail for writing two articles and publishing them on the internet, and during that time I have been through physical violence and mistreatment committed by security forces. I reported it but no one has been questioned or punished. That made me feel that there is no justice in my country and that it is easy to be humiliated and tortured and you will not get protected, since the judiciary system is practically part of the executive power and the judges do what the authorities want them to do.

Rahim Haciyev, deputy editor-in-chief of Azerbaijani newspaper Azadliq (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

Freedom of expression is the basis of all other rights and freedoms. Free speech is something all authoritarian regimes are worried about as it threatens their existence. That is why freedom of expression is specifically targeted by authoritarian regimes. If there are no free people, there is no freedom of expression. Free speech is a precondition for journalists to be able to work in full strength and thus fulfill their functions in society. Authoritarian regimes organise permanent attacks on journalists with impunity. A free journalist armed with freedom of expression is a threat to an authoritarian regime, this is why perpetrators receive awards, not punishment for oppressing journalists’ rights. This process leads to self-censorship, and journalists stop being carriers of truthful information, which in the end affects society.

Impunity is a threat to free expression because journalists and people who report the facts on the ground will feel danger, and if no one gets punished for crimes against journalists or others it establishes a systematic impunity culture. Feeling insecure is something bad, it stops people from having a normal life, functioning and expressing themselves.

Impunity is a threat for free expression on many levels. In my experience I have seen impunity when it cultivates self-censorship. Let’s take the case of Zone9 bloggers. Since their arrest there are a lot of people who tried to visit them in prison, take a picture of them, attend their trial and tweet about their hearings but all of these have invited very bad reactions from the Ethiopian police.

Some were arrested briefly, others were beaten and it has become impossible to attend the “trial” of the bloggers and journalists. No action was taken by the Ethiopian courts against the bad actions of the police even though the bloggers have contentiously reported the kinds of harassment. As a result, people have stopped tweeting, taking pictures and writing about the bloggers. Apparently, the volume of the tweets and Facebook status updates which comes from Ethiopia has dwindled significantly. People don’t want to risk harassment because of a single tweet or a picture. This self-censorship could be attributed to impunity, which is pervasive in Ethiopia.

Impunity also causes a lack of trust in the Ethiopian judicial system. I don’t trust the independence of the Ethiopian justice system. I have never seen a police man/woman or a government authority being prosecuted for their bad actions against journalists. The Ethiopian government has been prosecuting hundreds of journalists for criminal defamation, terrorism and inciting violence but not a single government person for violating journalists’ rights. This tells you a lot about the compromised justice system of the country.

Russia is known for its traditions of self-censorship. Despite what the laws say, the rules are explained in a quiet voice in some unmarked cabinets. Sometimes the rules are even not explained, and journalists, editors and owners of media have to constantly guess what is allowed at that moment. Not everyone is allowed to ask directly, so we are all in the game about signals sent by the authorities.

Journalists are beaten and killed in Russia, and this provides plenty of room to send such signals to the journalistic community. You don’t need to explain that investigative reporting in the North Caucasus is not allowed anymore: you just need to turn the investigation of Anna Politkovskaya’s assassination in 2006 into a show trial, where the assassins are duly found guilty, but the question of masterminds is never answered. You could be sure, the signal would be taken correctly.

Impunity allows the enemies of free speech to threaten, torture and kill journalists secure in the knowledge they will never be called to account. I can’t think of a greater threat.

In my 25 years of experience in Serbia, I have been editor-in-chief of a media outlet that was banned on several occasions and I have been arrested.

Impunity directly encourages and expands violence towards journalists. The culture of producing fear is the most efficient form of censorship. One unsolved murder creates space for implementing the next one without any threat for the executioners. In the meantime, the media gets killed/eliminated in the process.

The lack of discontinuity with Slobodan Milosevic’s authoritarian regime had left room for impunity to remain intact.

Less than two years ago, I decided to make a kind of a breakthrough when it comes to impunity. I proposed the establishment of a mixed commission composed of journalists, members of the police and members of the security information agency. We managed to bring the 1999 murder of Slavko Curuvija to a phase where official indictment was brought, along with arrest of all suspects in this murder case. The 2001 murder of our colleague Milan Pantic is also in the final stage of investigation. A 1994 assassination — of Dada Vujasinovic — is being reviewed by the National Forensic Institute from The Hague because local institutions have compromised themselves in this case.

In the same way as impunity restricts freedom of speech, solving of these cases, at least 20 years later, will surely contribute to journalists being encouraged to do their job in the best possible way. Of course, I am not counting here on the new problems with which journalists and media face, and that call for finding new models of financing high quality journalism for the sake of public interest, worldwide.

This year, we have seen a rising number of Chinese journalists, academics and human rights lawyers detained, threatened and arrested simply for speaking out online. While Chinese regulations on freedom of speech need to be closely examined, tech companies also play an important role in the deterioration of freedom of speech in China.

While Chinese tech companies are under the tight control of the Chinese authorities, there exists a culture of impunity in the western tech companies, especially when they are doing business in China. When we worked with our partner GreatFire to launch a FreeWeibo iOS application last year (an app to deliver uncensored content from Weibo, the largest social media platform in China), Apple decided to remove the app from their Chinese iTunes store. The only reason given was that Apple received a request from the Chinese authorities. This June, LinkedIn censored user posts deemed sensitive by the Chinese government on the global level, far beyond Beijing’s censorship requirement, even though LinkedIn does not have servers in China.

It would be the start of the end if these global tech companies start removing content simply because they do not want to upset their business relationships with China. It is crucial to hold these companies accountable for their behaviour. Otherwise it will further erode freedom of expression, not only for China, but also for the whole world.

The International Day to End Impunity was set up in 2011 by free speech network IFEX, of which Index on Censorship is a member, with the aim of demanding accountability and justice on behalf of those “targeted for exercising their right to freedom of expression”.