Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The recent AFP raids in Australia highlighted that challenges to media freedom are not limited to authoritarian countries.

It has been reported that since 9/11, Australia has seen the introduction or amendment of more than 75 sets of legislation, many of which may impinge on press freedom. Simultaneously, the debate about journalist and whistleblower protection laws has gained momentum.

But where does the security issue fit into this? While a successful democracy is characterised by a free press, it remains true that there are often good reasons for secrecy and confidentiality. How can we reconcile the conflicting perspectives of press freedom and security?

As part of the Integrity 20 conference, Index chief executive and 2019 Freedom of Expression Award winner Mimi Mefo join a panel of experts to discuss challenges to media freedom worldwide.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Tech journalist Geoff White (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

“Put your hand up if you’re concerned at the moment about facial recognition”, Geoff White, investigative technology journalist, told the audience at the launch of the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine. “Keep your hands up if you own a smartphone”, was White’s next instruction to the majority of the audience. “Good news. You’re already using facial recognition!”

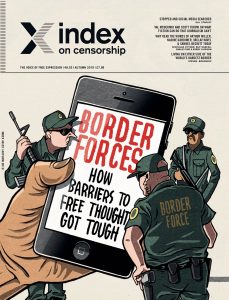

The autumn issue of the magazine, on the theme of borders, investigates how border forces around the world are increasingly clamping down on the free movement of ideas. The worrying and growing trend of travellers’ social media accounts being checked as they enter a country was a particular focus of the magazine. Contributors questioned whether people would begin to self-censor their online presence for fear of their views being held against them at airport security. This could pose particular dangers to LGBT travellers travelling through countries with repressive laws.

The launch was part of the Science Museum’s September’s late event, which takes place monthly. The theme of the night was Top Secret, and Index on Censorship shared the venue with talks about cracking codes and personal security. White was joined on stage by Jacob Wilkin, a penetration tester. Their talk was introduced by Rachael Jolley, editor of Index on Censorship magazine.

White highlighted the issues around the increasingly widespread use of facial recognition technology: the data that can be attached to the image of a face. Different stashes of data, bank and tax records for example, each have a unique number attached to them. He said: “But to really have power in this new world of data you need to get all the stashes together.” This requires one number that unites them all. “And guess what, we’ve had it along. It’s literally written on your face.” Facial recognition technology reduces an image of a face to a set of numbers and letters.

This comes into play at the world’s borders. International airports, including LAX and Gatwick Airport are employing facial recognition technology. The Transport Security Administration in the US have scanned 19,000,000 people to detect imposters. They detected 100. Is it worth collecting the data of so many to catch so few?

White said: “Think about the number of stashes of data that your face connects to. Your Facebook profile, your LinkedIn profile, your Twitter profile, your driver’s license, your passport, and increasingly every cctv camera you walk past.” Britain is second only to China for proliferation of CCTV cameras.

Network penetration specialist Jacob Wilkin (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

Wilkin demonstrated how easily computer programmes can find these social media accounts with minimal information. Wilkin describes himself as “a hacker for the good guys”, testing for flaws in the security of corporations and banks. He has created a facial recognition programme called Social Mapper.

Social Mapper correlates people’s social media profiles based on an image and a name that is fed into it. Days before the launch, Jodie Ginsburg, CEO of Index on Censorship, volunteered a photo of herself to Wilkin to run through his programme. Her Linkedin, Twitter and Facebook profiles promptly appeared on the wall behind Wilkin. “This took two minutes” he said. “If you run this over multiple days with multiple machines, you can collect all the Linkedin data for a whole organisation.”

“What are the border implications of this?” Wilkin asked. He has spoken at an event for US Department of Homeland Security, who are looking at “scraping social media profiles as people come into the country. They want to find links to drugs, smuggling, terrorism.”

Catching people who pose a threat to the safety of others is doubtless a good thing. But should it come at the price of the violation of the privacy of the general public? Social media provides platforms where people are free to air political views, and exhibit aspects of their lives, including sexual orientation. When crossing borders into countries where freedom of expression is limited and dissenters are punished, will knowing that this information is being instantaneously collected impact on how people use their right to freedom of expression online? [/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1569514532933-51b65a69-4c09-0″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Editor-in-chief Rachael Jolley argues in the autumn 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine that travel restrictions and snooping into your social media at the frontier are new ways of suppressing ideas” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Border Forces – how barriers to free thought got tough

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Border officials in some countries already seek to find out about your sexual orientation via an excursion into your social media presence as part of their decision on whether to allow you in” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”How barriers to free thought got tough” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F09%2Fmagazine-border-forces-how-barriers-to-free-thought-got-tough%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2019 Index on Censorship magazine looks at borders round the world and how barriers to free thought got tough[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”108826″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/09/magazine-border-forces-how-barriers-to-free-thought-got-tough/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Building trust in the media, achieving media sustainability, and ending impunity for murdered journalists are all issues that will be covered during the upcoming International Parliamentary Seminar on Media Freedom, which takes place in London on 9 – 11 September. The Council of Europe’s Platform for the Protection of Journalism and Safety of Journalists is relevant in this regard, as it seeks to gather and disseminate information on serious media freedom issues.

The platform was launched in 2014 in response to growing hostility toward journalists and media freedom in Europe, so as to swiftly and systematically notify the Council of Europe of pertinent issues and to empower it to take timely and coordinated action when necessary. Index on Censorship is proud to be one of the platform partners. Since 2015 we have submitted and co-sponsored nearly 300 alerts (notifications) to the platform about threats to media freedom and the safety of journalists.

Index on Censorship contributes to the platform, including by drawing on its Monitoring and Advocating for Media Freedom project, which monitors threats, limitations and violations related to media freedom in Azerbaijan, Belarus, Russia, Turkey and Ukraine. In 2018, 17 alerts were submitted to the platform relating to impunity for murdered journalists. Of these, 15 occurred in the countries covered by Index’s media freedom project: Turkey (2), Azerbaijan (2), Ukraine (5), and Russia (6).

In advance of the International Parliamentary Seminar on Media Freedom session on regional initiatives, which takes place on 10 September, Index on Censorship expresses the belief that the platform provides a model that could be replicated by other regions. Such a mechanism has the capacity to quickly draw on the knowledge and expertise of media freedom organisations and journalists’ networks, in order to promote media freedom and enhance the safety of journalists.

Index has noted with extreme concern that the number of alerts about serious threats to journalists’ lives has almost doubled on an annual basis since the launch of the Platform in 2015. We believe that stronger political commitment and practical engagement from politicians and governments is needed to support media freedom around the world. In Council of Europe states, this means that parliamentarians must fully engaging with the platform by ensuring that each alert receives a swift and comprehensive response. This is essential in order for the platform to fulfil its potential.

While Index on Censorship commends the UK’s commitment to press freedom, we note that since the beginning of 2018 seven Council of Europe alerts have concerned the UK: new counter-terrorism legislation; proposed internet regulation; the arrest of two journalists in September 2018; the killing of a journalist in April 2019; the continued impunity for the killing of a journalist who was murdered in 2001; an attack on a journalist in August 2019; and a government-backed arms fair’s (DSEI) refusal to grant two journalists accreditation. Four of these alerts have yet to receive a response.

Noting the UK’s role as one of the Council of Europe’s founding members, Index urges the UK to continue engaging with the platform and ensure it takes practical and concrete steps to promote the protection of media freedom in the UK. The UK should aim to set an example for other countries by providing prompt and detailed state replies to alerts.

Contact: Jessica Ní Mhainín, [email protected] [/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1567768197646-934f3ae2-fe70-1″][/vc_column][/vc_row]