2 Jun 2014 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Young Writers / Artists Programme

(Image: Shutterstock)

Unlike any previous time in the history of the world, there is a generation growing up today with unprecedented knowledge and power at their immediate and constant disposal. Their voices cannot be silenced, they can communicate with each other instantaneously from anywhere in the world. They are children of the internet, and they are politically and socially empowered in ways that are not yet clearly understood. Increasingly defining their identities online as much as offline, net-powered Millenials are collectively reshaping social norms — defining the legacy their generation will leave society. The internet is a product of, and a critical factor in, this legacy.

For example, the internet is a key medium for personal expression. Deliberately open-access and open-source architectures that transcend national boundaries means that the online world is a place where its users become increasingly accustomed to possessing both a platform and a voice regardless of their status in society. Even where it is dangerous to criticise politicians, or to practice a faith, or to be homosexual, the internet provides shelter in anonymity and the chance to meet like-minded people. In this way, the children of the internet have access to support, advice and assistance, but also to allies. Even the most isolated human can now take action with the power of a collaborative collective rather than as a lone individual, and they do so with an attitude that has become acclimatised to unfettered freedom of speech.

For the internet generation, this translates to their political actions online and often erupts into their offline behaviour, too. Online petitions gain infinitely more traction than their pen-and-paper twins, and the more anarchic side of the internet takes no prisoners in parodying public figures, as evinced recently with the numerous revisions of the recent “beer and bingo” tax cut advertisements produced by the ruling coalition. More controversially, Wikileaks infamously released hundreds of thousands of classified government communiqués, and “hacktivist” groups such as Anonymous make their presence felt with powerful retaliations against firms and governments that they perceive to have suppressed internet freedom. Even high-security sites such as the US Copyright Office and Paypal have been targeted — civil disobedience that is symptomatic of the new, sharing internet generation that is paradoxically mindful of personal privacy and disparaging of public opacity.

For the strongest demonstration of the way this attitude and power translates, look no further than the violent reaction of a primarily young body of protesters during the Arab Spring and in Ukraine. The internet was the conduit through which popular campaigns against ruling regimes transformed into widespread civil disobedience and a full-blown political movement. Empowered with access to forms of political commentary comparatively free of governmental intervention and the ability of every protester to act as a professional journalist by virtue of a camera phone and a Twitter account, the children of the internet communicated, mobilised and acted to cast away governments from Tunisia to Yemen; Egypt twice over. They made their voices heard: not at the ballot box as previous generations might have, but in the streets of Cairo and Sana’a and the virtual spaces of Facebook and Blackberry Messenger. Small wonder then, that governments targeted and blocked social networking sites to quell dissent. In many countries the internet was shut down altogether.

Yet, the internet persevered — as John Gilmore, co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation noted: “The internet treats censorship as a malfunction and routes around it”. Despite the long running tussle between the users of the internet and governments who seek to regulate it, it remains untameable. In each instance, almost immediately after internet usage has been restricted, information has circulated about circumventing government regulations — even total shutdowns have been dodged through external satellite connections.

Powered overwhelmingly by the young, the internet is changing the way our societies are structured. Its effects upon our civilisation are poorly understood, particularly among young people who have never known a world without the internet. Ultimately, however, it has done more for individual freedom than any other development in the last half-century. It grants any person a voice with mere access to a keyboard and a broadband connection. It holds governments to account in new and innovative ways, and most crucially, it is an irreversible development. An entire generation defines itself, subconsciously, through the internet; previous such advancements came only through the invention of the printing press, radio and television. One thing is for certain — as broadband usage approaches saturation in many developed countries, we are all children of the internet now.

This article was originally posted on 2 June, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Apr 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society, United Kingdom, Young Writers / Artists Programme

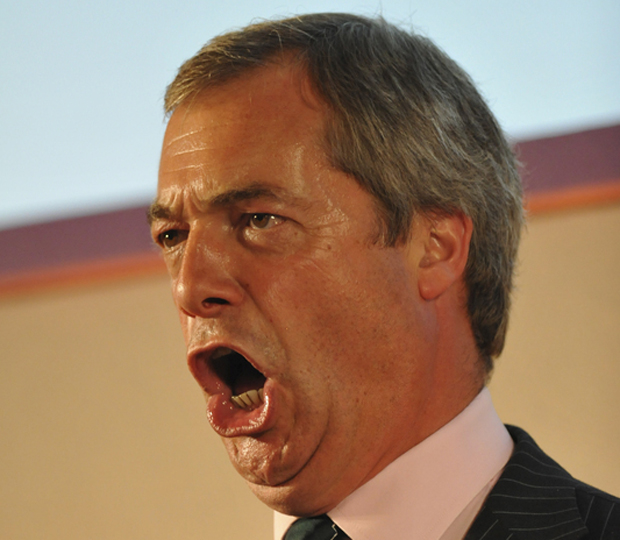

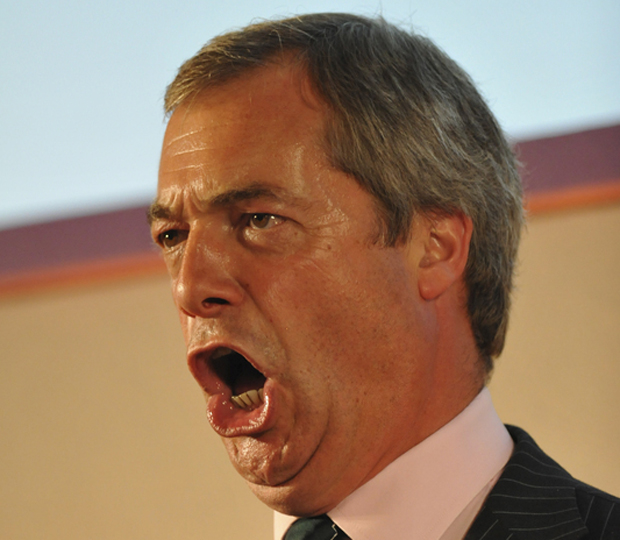

(Photo: Michael Preston / Demotix)

Ofcom’s decision to declare the UK Independence Party a ‘major party’ for the purposes of this month’s European elections has led to questions about who should be allowed to address the public. Behind the scenes, broadcasters have asked why their right to editorial freedom is restricted at all.

UKIP’s leader, Nigel Farage, responded: “This ruling does not cover the local elections, despite UKIP making a major breakthrough in the county elections last year. This strikes me as wrong.”

Natalie Bennett, leader of the Green Party – which Ofcom decided was not a major party – pointed out that, unlike UKIP, her party has an MP, and is also “part of the fourth-largest group in the European Parliament”.

Both sides pounced on the Liberal Democrats, whose dwindling position in the polls, they hinted, should see it demoted to minor party status.

The decision means commercial TV channels that show party election broadcasts must allow UKIP the same number of broadcasts as the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats. They will also be given equal weight in relevant news and current affairs programming. However, for content focusing on, or broadcasting solely to, Scotland, UKIP’s lower levels of support there mean it will remain a minor player.

This of course gives UKIP a certain level of legitimacy, and the scope to influence even more voters. For those campaigning against them, the move is grossly unfair.

The Green Party in particular feels hard done by. From the House of Lords to local councils it has representatives at every level, but Ofcom still claims it hasn’t achieved enough. Yet in its report the regulator said that it could not make UKIP a major party in Scotland without granting the same status to the Scottish Green Party, due to their comparable performance.

Ofcom has promised to review the list periodically, so things could change in future. But for now it believes the list represents political realities. UKIP’s focus on getting Britain out of Europe has helped it to do well at the past few European elections. In 2009 it came second in terms of vote share, up from third place in 2004, and this year a number of polls indicate that it could win. In more recent local elections UKIP has done well, achieving 19.9 per cent of the total vote in 2013. But this has leapt up from 4.6 per cent in 2009’s local elections, which for Ofcom is not consistent enough to justify extra coverage for its prospective councillors.

So it seems fair enough that UKIP counts as an important party for Britain in the European Parliament. The Greens are yet to win enough votes in enough elections for their inclusion to make sense. And the Liberal Democrats appear to be clinging on only because of their level of support in past general elections, which was also taken into account.

But the real question is why a list is necessary at all. After all a “regulated free press” sounds something like “freedom in moderation” – ultimately a nonsense. Ofcom’s control over which parties receive coverage puts a dampener on broadcasters’ right to freedom of expression and makes it more difficult for newer parties to break through.

Responding to a previous consultation on whether the list of major parties should be reviewed, Channel 4 said the regulator’s rules should “ensure that political messages are conveyed in a democracy… [but] such regulation should be as narrow as possible to restrict… any interference with the broadcaster’s right to editorial independence and its rights to freedom of expression”. Channel 5, meanwhile, said the concept of major parties did not have “continuing relevance at a time of increasing political flux and fragmentation within the electorate”.

Ofcom appears to be prioritising the need of the electorate to be informed. So it could be argued that, for the purposes of allocating party election broadcasts, the list is useful to prevent any channel from steadfastly omitting information on a party that is likely to appear on most voters’ ballot papers.

But in terms of news and current affairs programming, there seems little reason that broadcasters shouldn’t have the freedom to say what they please – particularly because newspapers are faced with no such restrictions.

As the dominance of mass media fades, and the internet provides access to alternative points of view, the restrictions on the news you receive through your TV will only become more obvious.

This article was originally published on April 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

29 Apr 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society, Uganda, Young Writers / Artists Programme

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

As a master student of Conflict and Development at the University of Ghent, Jos Van Steelandt will write a dissertation on the subject of censorship on and self-censorship within the media in Uganda. Because of his background as a historian specialised in Ugandan media-history and his interest in human rights, he chose this politically sensitive topic. In July, he will be conducting interviews with journalists working in Uganda. He will be keeping Index on Censorship up to date on his research during his trip.

In Uganda, journalists are not only dealing with outright censorship. It seems the government of president Yoweri Museveni is employing a strategy that is aimed at pushing journalists towards self-censorship using a broad range of measures. Although the Ugandan media has a very strong tradition of critical reporting some journalists are probably more prone to self-censor.

The use of force by its security forces serves to stifle critical voices appears widespread. A local human rights organisation, Human Rights Network for Journalists-Uganda, states in its latest report that in 2012 there were 124 violations of press freedom. A staggering 83% of these violations against journalists were committed by state-actors, among which police forces incorporate the large majority of the perpetrators. The structural nature of these violations and especially the contexts of the violations seems to suggest that this would be the result of an active government policy.

Apart from this outright aggression, the security forces in cooperation with the Uganda Communications Commission are able to close down editorial offices, as happened to one of Uganda’s leading newspapers, The Monitor, in 2013. This newspaper, known for its critical stance towards the government, was shut down for a couple of days after publishing a leaked confidential letter by General Sejjusa, which contained very compromising information about president Museveni’s familypresident. This event underlined to Ugandan news organisations that publishing on politically sensitive topics is not without risk.

Security forces also create an atmosphere in which critical reporting is discouraged by arresting journalists arbitrarily. Renowned Ugandan journalist Andrew Mwenda, for instance, was arrested 16 times. Most of the journalists who are arrested, are released shortly after, but the message towards journalists is once again clear.

Uganda’s legal code is another possible cause of self-censorship. Various laws give the government and security forces the possibility to constrain essential freedoms and even contradict the Ugandan constitution. The Public Order Management Bill, the Uganda Communications Act, the Press and Journalist Act and the Penal Code Act contain provisions that can be and are being used to hamper journalists. Journalists are often sued for libel or sedition or get bogged down in other lawsuits concerning their work. Journalists are made painfully aware that critical reporting implies walking the line within this legal framework.

The theory of the ‘chilling effect’ suggests that Uganda’s legal regime creates the possibility to clamp down on journalists and will have negative consequences on their work. This regulatory environment, in combination with the threat of violence and arrest, could make the large majority of journalists working in Uganda less willing to cover sensitive topics or could make them use mitigating discourse in their reports.

This July, I will conduct interviews with journalists of different news organisations working in Uganda. In these interviews, I will ask them for their personal experiences working as a journalist, but also ask them for the stories they think are interesting about other journalists who have had a run-in with the state. These stories, called control parables, that circulate among journalists, can tell us a lot about what journalists consider behaviour that will result in a run-in with the state. It can show us in which way most journalists will censor themselves even though the state hasn’t explicitly told them so. When we lay bare these mechanisms and research why some journalists are more vulnerable to self-censor, we can begin to think about possible measures that donors or NGO’s can take to make journalists less prone to self-censor on politically sensitive but still important issues. These possible measures include providing insurance or legal protection for journalists and campaigning to implement some sort of Chilling-effect principle in the Ugandan legal code. This principle is being implemented in the European Court of Human Rights and can be invoked when a certain law threatens to impose silence upon journalists in cases of politically sensitive topics.

Three more months and I’m off to do my fieldwork in Kampala, Uganda. I will try to bring you the stories of the journalists I interview and share the experiences they encountered working as a journalist in ‘the pearl of Africa’. I’ll keep you posted!

This article was posted on April 25, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Apr 2014 | Americas, News and features, United States, Young Writers / Artists Programme

(Image: Bplanet/Shutterstock)

(a list poem)

Because if you’re an artist, you never know where you’ll go.

Because you need a personal identity number to send a package.

Because an IP address is not a perfect proxy for someone’s physical location, but it is close.

Because I do most of my research online.

Because there hasn’t been a proper rain in California in over three years, and this year may be the driest in the last half millenium.

Because the burning of fossil fuels is destroying our atmosphere.

Because persistent cookies are stored on the hard drive of a computer until they are manually deleted or until they expire, which can take months or years.

Because tracking cookies are commonly used as ways to compile long-term records of individuals’ browsing histories.

Because server farms require massive amounts of energy.

Because the friend who wanted to send the email “Photos from Taksim Square” couldn’t until she changed the subject to “Paris Vacation Photos”.

Because the line between “public” and “private” is tenuous at best.

Because the ACLU is doing its best.

Because a webcam’s images might be intercepted without a user’s consent.

Because a surveillance program code named “Optic Nerve” was revealed to have compiled and stored still images from Yahoo webcam chats in bulk in Great Britain’s Government Communications Headquarters’ databases with help from the United States’ National Security Agency, and to be using them for experiments in automated facial recognition.

Because it’s sketchy to be a Communist.

Because the Defending Dissent Foundation is all kinds of busy.

Because the U.S. army actively targeted nonviolent antiwar protestors in Washington in 2007.

Because I saw it on Dronstagram.

Because everything will or might end up on the internet.

Because the internet is a wormhole full of parasites.

Because I am trying to connect all of the dots.

Because free speech is a tinted mirror.

Because all mediated information is processed, edited, and altered.

Because Wally Shawn had to bring his play to Glenn Greenwald since the journalist who broke the story about Edward Snowden can’t return to the United States.

Because the author risked his freedom and physical security for the truth.

Because artistic solidarity is framed as criminal complicity.

Because how could I forget that language is always political?

Because Chelsea Manning is still being misgendered.

Because the personal is always political.

Because it’s not just the major political players.

Because of the metadata collection.

Because a local surveillance hub may start out combining video camera feeds with data from license plate readers, but once you have the platform running, police departments could plug in new features, such as social media scanners.

Because the Domain Awareness Center’s focus has been not on violent crime, but on political protests.

Because the collapse of the economy and the devastation of the environment are two sides of the same coin.

Because of the NSA’s presence at UN climate talks.

Because of the vested interests in the oil industry.

Because tell me something I don’t know.

Because my personal information is probably being used not just for advertising purposes.

Because despite Facebook’s rights and permissions policies, I still want to share with my friends.

Because Pussy Riot was imprisoned.

Because the Trans-Pacific Partnership would rewrite rules on intellectual property enforcement, giving corporations the right to sue national governments if they passed any law, regulation, or court ruling interfering with a corporation’s expected future profits.

Because I don’t know who is making money off of my information.

Because Abstract Expressionism was funded by the CIA.

Because of the time-honored tradition of governments keeping tabs on artists.

Because we don’t want jobs, we want to live.

This poem was posted on April 25, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org