2 Dec 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.04 Winter 2015

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”What can’t people talk about? The latest magazine looks at taboos around the world”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

What’s taboo today? It might depend where you live, your culture, your religion, or who you’re talking to. The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores worldwide taboos in all their guises, and why they matter. Comedians Shazia Mirza and David Baddiel look at tackling tricky subjects for laughs; Alastair Campbell explains why we can’t be silent on mental health; and Saudi Arabia’s first female feature-film director Haifaa Al Mansour speaks out on breaking boundaries with conservative audiences.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”60px”][vc_single_image image=”71995″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Plus a crackdown on porn and showing your cleavage in China; growing up in Germany with the ghosts of WW2; what you can and can’t say in Israel and Palestine; and the argument for not editing racism out of old films. As the anniversary of Charlie Hebdo murders approaches, we also have a special section of cartoonists from around the world who have drawn taboos from their homelands – from nudity, atheism and death to domestic violence and necrophilia.

Also in this issue, Mark Frary explores the secret algorithms controlling the news we see, Natasha Joseph interviews the Swaziland editor who took on the king and ended up in prison, and Duncan Tucker speaks to radio journalists who lost their jobs after investigating presidential property deals in Mexico.

And in our culture section, Chilean author Ariel Dorfman looks at the power of music as resistance in an exclusive short story, which is finally seeing the light after 50 years in the pipeline. We have fiction from young writers in Burma tackling changing rules in times of transition, and there’s newly translated poetry written from behind bars in Egypt, amid the continuing crackdown on peaceful protest.

Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide. Order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year).

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: WHAT’S THE TABOO? ” css=”.vc_custom_1483453507335{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Why breaking down social barriers matters

Stand up to taboos – Shazia Mirza and David Baddiel on how comedy tackles the no-go subjects

The reel world – Nikki Baughan interviews female film directors Susanne Bier and Haifaa Al Mansour, from Denmark and Saudi Arabia

Not just hot air – Kaya Genç goes inside Turkey’s right-wing satire magazine Püff

Slam session – Péter Molnár speaks to fellow Hungarian slam poets about what they can and can’t say

Whereof we cannot speak – Regula Venske on growing up in Germany after WWII

China’s XXX factor – Jemimah Steinfeld investigates a crackdown on porn and cleavage

Pregnant, in danger and scared to speak – Nina Lakhani and Goretti Horgan on abortion laws and social stigma in El Salvador and Ireland

Airbrushing racism – Kunle Olulode explores the problems of erasing racist words from books and films

Why are we whispering? – Alastair Campbell on why discussing mental illness still makes some people uncomfortable

Shouting about sex (workers) – Ian Dunt looks at the debate where everyone wants to silence each other

The history man – Professor Mohammed Dajani Daoudi explains how he has no regrets, despite causing outrage after taking Palestinian students to Auschwitz

Provoking Putin – Oleg Kashin on how new laws are silencing Russians

Quiet zone: a global cartoon special – Featuring taboo-busting illustrations from Bonil, Dave Brown, Osama Eid Hajjaj, Fiestoforo, Ben Jennings, Khalil Rhaman, Martin Rowson, Brian John Spencer, Padrag Srbljanin, Toad and Vilma Vargas

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Reining in power – Natasha Joseph talks to the Swaziland editor who took on the king

Whose world are you watching? – Mark Frary explores the secret algorithms controlling the news we see

Bloggers behind bars – Ismail Einashe interviews Ethiopia’s Zone 9 bloggers

Mexican airwaves – Duncan Tucker speaks to radio journalists who were shut down after investigating presidential property deals

Head to head – Bassey Etim and Tom Slater debate whether website moderators are the new censors

Off the map – Irene Caselli on how some of the poorest people in Buenos Aires fought back against Argentina’s mainstream media

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

The rocky road to transition – Ellen Wiles introduces new fiction by young Burmese writers Myay Hmone Lwin and Pandora

Sounds of solidarity – Chilean author Ariel Dorfman presents his short story on the power of music as resistance

Poetry from a prisoner – Omar Hazek shares his verses written in an Egyptian jail and translated by Elisabeth Jaquette

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view – Index on Censorship’s CEO, Jodie Ginsberg, on the pull between extremism legislation, free speech and terrorism

Index around the world – Josie Timms presents Index’s latest work and events

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

18 Aug 2015 | India, mobile, News, Youth Board

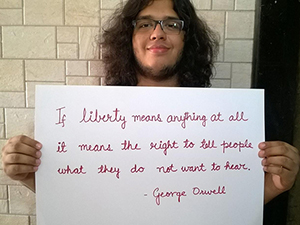

This is the third of a series of posts written by members of Index on Censorship’s youth advisory board.

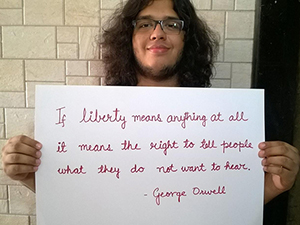

Members of the board were asked to write a blog discussing one free speech issue in their country. The resulting posts exhibit a range of challenges to freedom of expression globally, from UK crackdowns on speakers in universities, to Indian criminal defamation law, to the South African Film Board’s newly published guidelines.

Harsh Ghildiyal is a member of the Index youth advisory board. Learn more

Sections 499 and 500 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, which criminalise defamation, have been challenged before the Supreme Court of India. In addition, sections of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, which provide the procedure for prosecution, have been challenged.

Over the years, through several cases, the Supreme Court has made it clear that restrictions in place on speech must be reasonable, and only to the extent that they are necessary. Defamation is expressly listed as one of these reasonable restrictions but criminal defamation is not in the least bit reasonable. If the restriction goes beyond the intended purpose, it must be struck down.

Criminal defamation cases have been filed against the media, politicians and individuals for their statements. While adequate remedies for defamation exist under civil law, the provision criminalising defamation provides for imprisonment of up to two years, a fine or both. The punishment is disproportionate to an act which doesn’t go against society but against individuals.

More often than not used for dampening legitimate criticism rather than actually serving its purpose, criminal defamation is clearly not a reasonable restriction and can act as an impediment to free speech.

Harsh Ghildiyal, India

Related:

• Jade Jackman: An act against knowledge and thought

• Tom Carter: No-platforming Nigel

• Matthew Brown: Spying on NGOs a step too far

• About the Index on Censorship youth advisory board

• Facebook discussion: no-platforming of speakers at universities

12 Mar 2015 | India, News

A scene from the recently released documentary India’s Daughter (Image: BBC)

Whoever, intending to insult the modesty of any woman, utters any word, makes any sound or gesture, or exhibits any object, intending that such word or sound shall be heard, or that such gesture or object shall be seen, by such woman, or intrudes upon the privacy of such woman, shall be punished with simple imprisonment for a term which may extend to one year, or with fine, or with both.

– Section 509, Indian Penal Code

“The lady…or the girl, or woman, is more precious than a gem, a diamond. It is up to you how you want to keep that diamond in your hand.”

“Someone put his hand inside her and pulled out something long. It was her intestines.”

“My husband told me I was stupid because I went to protest and didn’t think about the consequences”

– From the documentary India’s Daughter

The rape and murder of Jyoti Singh on a bus in Delhi in December horrified much of India and the world. Rape is by definition an act of violence and violation, but the details of the brutality meted out by the gang of six attackers were particularly shocking. Singh was flown to a specialist hospital in Singapore, but eventually succumbed to her injuries.

The 23-year old had been returning home from a trip to the cinema to see The Life Of Pi with a male friend. Of course, in discussions of rape, it does not matter what the victim was doing; where the victim was going, or when, or why or with whom. But it was extraordinary how the “asking for it” argument was extended in the prosecution of Singh’s killers.

Watching the BBC’s stunning India’s Daughter documentary was a disturbing experience. Singh had not gone out alone, it was true. She had not gone to a bad part of town: but she had gone out in the evening, with a man who was not a family member. That was enough.

She was female in public. That was enough to justify the attack. One attacker spoke of taking “pleasure” where you found it: the rich man will pay for his “pleasure”, the poor man will attain it “through courage” — that is, rape.

India’s Daughter was a shocking, grim and important hour of television that laid the misogyny of society bare for all to see. All, that is, except Indian BBC viewers, who were denied the opportunity to watch the documentary.

The Indian government obtained an injunction barring the film being shown in the country after it emerged the filmmakers had interviewed one of the rapists, Mukesh Singh. The attacker was apparently unrepentant, repeating the mantra that a “good girl” would not have got herself into the situation where he raped her.

Indian Home Minister Rajnath Singh was appalled, saying: “It was noticed the documentary film depicts the comments of the convict which are highly derogatory and are an affront to the dignity of women.” The government invoked section 509 of the Indian penal code

So the film was banned from television. And then later from YouTube in India. An hour of forensic, challenging film-making, exploring violence against women and the attitudes around violence against women was censored in order to protect women’s honour — a woman’s “honour” being patriarchy’s most precious bauble. Indian society had failed to protect Jiyoti Singh in life and now, still, she, through her story, was to be denied access to public space in death. This is not how we “protect” women.

It is not the job of society to “protect” women: rather it is the job of society to ensure women’s rights. This is not done by keeping quiet, or suggesting that women keep quiet, but rather by talking loud and clear.

This week, Naz Shah, the Labour parliamentary candidate for Bradford West (where she will challenge George Galloway) became an instant star after an article about her life and what had driven her to seek political office. Her mother had been brutalised for years. Shah’s father had run off with another woman, and her mother sought shelter for herself and her children with another man. But she found torture, not sanctuary. After years of abuse, Shah’s mother killed her tormentor. Following campaigning work from the ever-inspirational Southall Black Sisters, Shah’s mother Zoora saw her jail sentence for the killing reduced from 20 years to 12.

Borrowing a phrase from Barack Obama, Shah described how her political ambition had stemmed from the “dream of her mother”. After Shah’s father left, it was the mother, the innocent party, who was left with the shame, the besmirched honour. While in prison, Zoora Shah told her daughter that she would like to see her become a prison governor, so that she could help women in incarceration. Shah’s impulse ever since, she says, was to be in a position to influence change.

But still she realises there will be people who are not interested in women taking up public spaces. “Already my ‘character’ has been attacked and desecrated through social media and trolling. The smear campaign that has started has been some of the most vicious and disgusting I have seen. But it does not scare me, will not change me, and it in fact fuels my passion for change more,” she wrote for Urban Echo.

The impulse to deny women the right to exist in public is not limited to the streets of Delhi, or Bradford. Think of the threats received by feminist Caroline Criado Perez, by MPs such as Stella Creasy and Luciana Berger. Think, even of the sexist chants against female officials and staff that have been highlighted by the Football Association recently. The language may be openly hateful, or couched in “protective” metaphor, but the message is always clear. The public sphere, public interaction, is for men, and at best, you are here by our permission. But the question is not, fundamentally, about who grants permission. As long as we accept that that power belong to one group and not the other, then we are accepting and entrenching inequality. The aspiration is to smash any idea of who is “allowed” to go where, who is allowed to wear what, who is allowed to say what. In an equal world, there can be no concept of “permission” being granted by one group to another. Instead, as Naz Shah wrote, there must be “real meaningful and honest conversations not only with ourselves but with our families, our communities and beyond”.

This column was posted on 12 March 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

23 Jan 2015 | News

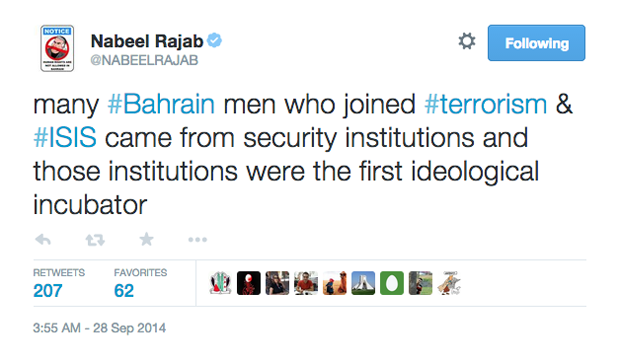

Bahrain

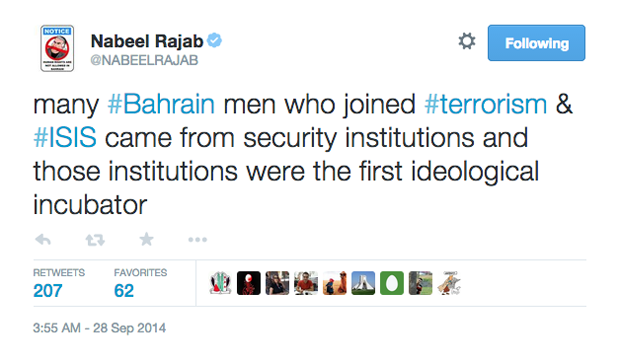

This week, prominent Bahraini human rights activist Nabeel Rajab was handed down a six month suspended sentence over a tweet in which both the country’s ministry of interior and ministry of defence allege that he “denigrated government institutions”. Rajab was only released last May after two years in prison, over charges that included sending offensive tweets. His experience is not unique in Bahrain. In May 2013, five men were arrested for “insulting the king” via Twitter.

Turkey

A former Miss Turkey was recently arrested for sharing a satirical poem criticising the country’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on her Instagram account. She is set to go on trial later this year. Turkey has a chequered relationship with social media, temporarily banning both Twitter and YouTube in the wake of the Gezi Park protests, in large part organised and reported through social media. In 2013, authorities arrested 25 individuals for spreading “untrue information” on social media.

Saudi Arabia

(Photo: Gulf Centre for Human Rights)

In late 2014, women’s rights activist Souad Al-Shammari was arrested during an interrogation over some of her tweets. The charges against her include “calling upon society to disobey by describing society as masculine” and “using sarcasm while mentioning religious texts and religious scholars”, according to the Gulf Centre for Human Rights.

France

![(Photo: « Source : Réseau Voltaire » [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Dieudonné_Axis_for_Peace_2005-11-18.jpg)

(Photo: Réseau Voltaire [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

Following the series of terrorist attacks in Paris in early January, at least 54 people have been detained by police for “defending or glorifying terrorism”. A number of the cases, including against comedian Dieudonne M’bala M’bala, are believe to be connected to social media comments.

Britain

A 22 year old man was arrested in for “malicious communication” following Facebook messages made in response to the murder of soldier Lee Rigby, and another user was arrested after taunting Olympic diver Tom Daly about his dead father. More recently, police arrested a 19-year-old man over an “offensive” tweet about a bin lorry crash in Glasgow that killed six people. TV personality Katie Hopkins, known for her controversial tweets, was also reported to Scottish police following some tasteless tweets about about Scots. The incident prompted Scottish police the to post their now infamous tweet declaring they would continue to “monitor comments on social media“.

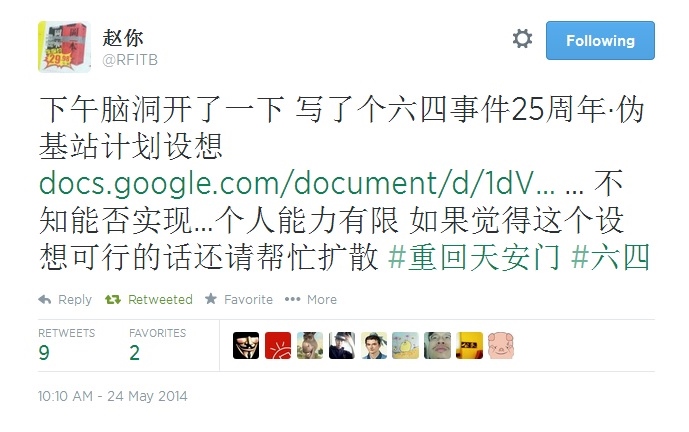

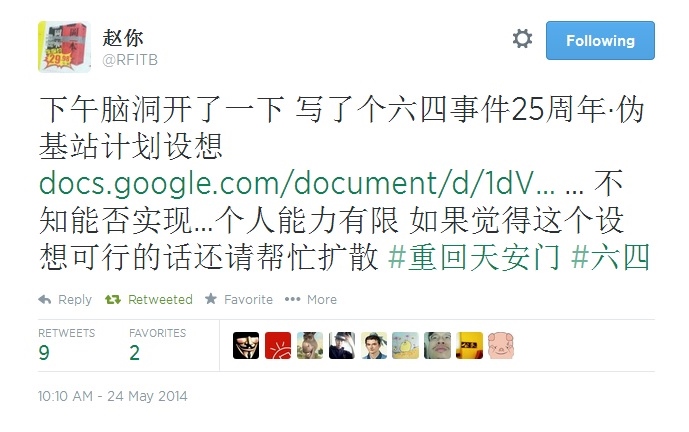

China

Online activist Cheng Jianping was arrested on her wedding day in 2010 for “disturbing social order” by retweeting a joke by her fiance. She was sentenced to one year of “re-education through labour”. Twitter is officially banned in China, and microblogging site Weibo is a popular alternative. In 2013, four Weibo users were arrested for spreading rumours about a deceased soldier labelled a hero and used in propaganda posters. The four were said to have “incited dissatisfaction with the government”, according to the BBC.

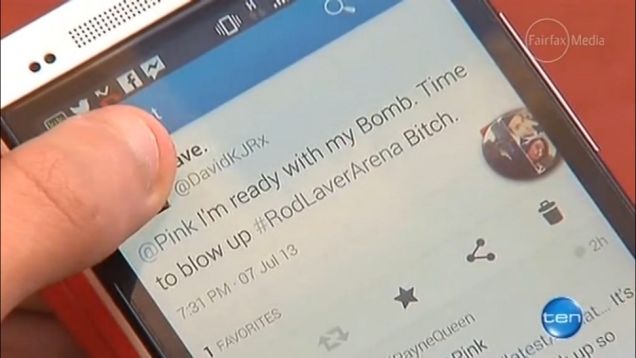

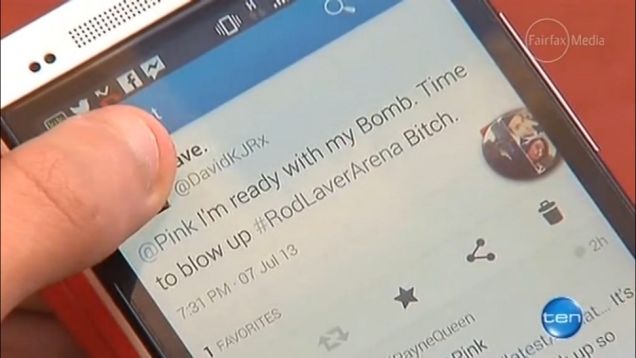

Australia

A teen was arrested prior to attending a Pink concert in Melbourne for tweeting: “I’m ready with my Bomb. Time to blow up #RodLaverArena. Bitch.” The tweet referenced lyrics from the American popstar’s song Timebomb.

India

An Indian medical student was arrested in 2012 over a Facebook post questioning why her city of Mumbai should come to a standstill to mark the death of a prominent politician. Her friend was arrested for liking the post. Both were charged with engaging in speech that was offensive and hateful.

United States

Back in 2009, a New York man was arrested, had his home searched and was placed under £19,000 bail for tweeting police movements to help G20 protesters in Pittsburgh avoid the officers. According to Global Voices, it is unclear whether his actions were actually illegal at the time.

Guatemala

A man was arrested in 2009 for causing “financial panic” by tweeting that Guatemalans should fight corruption by withdrawing all their money from banks.

This article was posted on 23 January, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![(Photo: « Source : Réseau Voltaire » [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Dieudonné_Axis_for_Peace_2005-11-18.jpg)