21 Nov 2013 | Digital Freedom, India

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

Full report in PDF

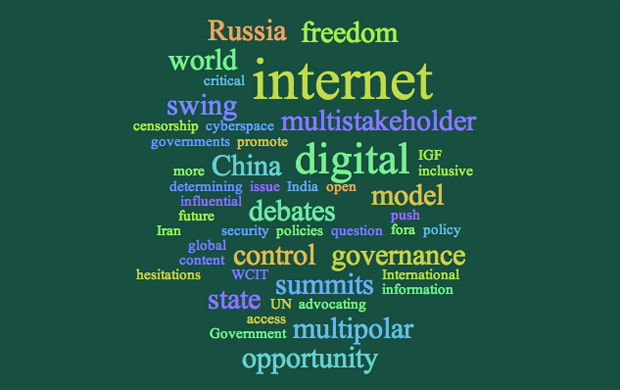

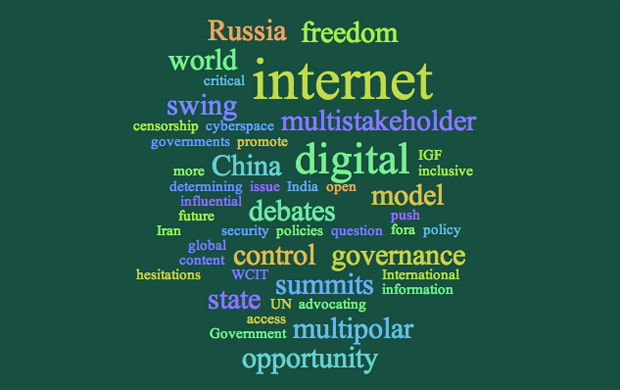

(5) INDIA’S ROLE IN GLOBAL INTERNET DEBATES

International summits and fora over the next two years will be critical in determining the internet’s future. The open and inclusive multistakeholder model of internet governance has been called into question, with some governments – namely China, Iran and Russia – advocating for more control. As an influential state in our increasingly digital and multipolar world, India has the opportunity to push policies that promote digital freedom. Yet, India is still very much a swing state in these internet governance debates.

After initial scepticism, India has now joined the European Union (EU) and the US in resisting the call for a top-down government-led approach for global internet governance. At the World Conference on International Telecommunication in Dubai in December 2012, India was one of the few countries to side with EU member states and the US in supporting the current multistakeholder status quo. This was the result of a debate in India, in which the key battle line was whether internet freedom constituted a daunting threat to security that required top-down national control or not.

India’s hesitation increased after the 2008 Mumbai attacks when Jaider Singh, Secretary of the Department of Information Technology, described the internet as “both a vehicle and a target of criminal minds”.[49] Concerns over security and spam led India to advocate for more national control over internet governance, through the creation of a United Nations committee.[50] Earlier in 2011 at the Internet Governance Forum in Nairobi, India, along with South Africa and Brazil – two other crucial swing states in the internet governance debate – proposed a similar initiative.

While such top-down control has long been advocated by the likes of China and Iran – countries with a poor domestic track record on digital freedom – it is a direct threat to internet openness and the exercise of human rights online by placing too much control of the process in the hands of national governments. The EU and US tried to address India’s concerns diplomatically by agreeing to a working group.

It is positive that India is now willing to play an important role in defending the multistakeholder model of internet governance against calls for more top-down state regulation. Yet, it is clear that with a sixth of the world’s population, it is not just important for India’s government to defend internet freedom globally, but also ensure that its domestic record stands up to scrutiny and is a model for the rest of the world to adopt. Currently, this is not the case.

India is not only setting internet policies for its 10 percent of users today, but for its 1 billion citizens yet to come online. The decisions it makes, both domestically and on the international stage, are likely to set powerful precedents for regional neighbours, and other emerging democratic powers.

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

This report was originally posted on 21 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[49] Jaider Singh, speaking at the third annual Internet Governance Forum in Hyderabad, India, in 2008 with the theme ‘Internet for All.’ Internet Governance Forum, ‘Internet Governance Forum Concludes Hyderabad Meeting’ (6 December 2008), http://www.elon.edu/docs/e-web/predictions/IGF 08 Daily Highlights Dec 6.pdf accessed on 10 September 2013.

[50] In 2011, India proposed a United Nations Committee for Internet-Related Policies (CIPR) be established to develop and oversee internet policies that would affect the world’s users. Techdirt, ‘India Want UN Body To Run The Internet: Would That Be Such A Bad Thing?’ (2 November 2011), http://www.techdirt.com/articles/20111102/04561716601/india-wants-un-body-to-run-internet-would-that-be-such-bad-thing.shtml accessed on 2 September 2013.

21 Nov 2013 | Digital Freedom, India

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

Full report in PDF

4. ACCESS: OBSTACLES AND OPPORTUNITIES

Key concerns in assessing online freedom of expression in India are the barriers to accessing the internet itself. There are a number of major obstacles to online access in India namely infrastructural limitations, cost considerations as well as illiteracy and language. In addition, this section argues that security considerations have created further barriers for Indian people to access the internet.

With around 120 million web users – 12.6 percent of India’s population – internet penetration is relatively low by global standards. Yet as cheaper smartphones enable millions more to access the net, usage is increasing and the government is prioritising digital access and development as a political objective. Digital access initiatives are being developed in India to fight illiteracy and poverty, promote Indian language content online, increase broadband penetration and speed in rural and urban areas, and improve the reliability of electricity.[42]

In May 2006, the government approved a National e-Governance Plan to implement national e-governance with the aim to make all government services accessible to localities. This project aims to connect more Indian citizens through the National Optic Fibre Network and takes into account the need to increase internet access in the country.[43]

One of the major barriers to access online content is language. There are 22 primary regional languages in India, but most online content is in English, a language only 11 percent of the population can read.[44] Civil society initiatives have moved quicker than the government. Journalist Shubhranshu Choudhary has created the news platform CGNet Swara, which lets people use their mobile phone to listen to and leave their own stories, bringing news to communities who don’t speak Hindi or English, and are therefore denied access to mainstream newspapers or news websites.[45]

Broadband access and the price remains a major barrier to digital freedom of expression with only 3% of households having a fixed internet connection in 2012.[46] For this reason, many Indian users access the internet via cybercafés. However in 2011, fearing that cybercafés facilitated criminal and terrorist activities, the Indian Government introduced strict rules restricting cybercafés under Section 79 of the IT Act.

Many have denounced the cybercafé rules as restricting access to cybercafés and infringing Indian citizen’s freedom of expression and privacy rights.[47] The rules are problematic in many ways. Firstly, they limit the creation and sustainability of cybercafés by imposing draconian administrative requirements. For example, cybercafés must also have the capacity to retain user identity information and the log register in a secure manner for a minimum period of a year. Secondly, the rules directly limit citizens’ access to cybercafés. Cybercafés cannot allow users to use computer resources without providing an established identity document, a barrier for poorer people in rural communities who are disproportionately likely not to have the required identification.

India faces numerous obstacles to internet access, from infrastructural limitations to costs and language restrictions.[48] While government efforts to increase broadband penetration and speed in rural and urban areas are welcome, restrictions on access to and the functioning of cybercafés must be lifted.

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

This report was originally posted on 21 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[42] Hari Kumar, New York Times, India Ink (Blog), ‘In India Homes, Phones and Electricity on Rise but Sanitation and Internet Lagging’ (14 March 2012), http://india.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/14/in-indian-homes-phones-electricity-on-rise-but-sanitation-internet-lagging/ accessed on 11 September 2013.

[43] Government of India, National e-Governance Plan, http://india.gov.in/e-governance/national-e-governance-plan

[44] OpenNet Initiative, ‘Country Profile: India’ (9 August 2012) https://opennet.net/research/profiles/india accessed on 10 September 2013.

[45] Rachael Jolley, Index on Censorship, ‘India calling’, ‘Not heard? Ignored, suppressed and censored voices’, Volume 42, Number 03, September 2013.

[46] Hari Kumar, New York Times, India Ink (Blog), ‘In India Homes, Phones and Electricity on Rise but Sanitation and Internet Lagging’ (14 March 2012), http://india.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/14/in-indian-homes-phones-electricity-on-rise-but-sanitation-internet-lagging/ accessed on 11 September 2013.

[47] Information Technology [Guidelines for Cybercafés] Rules, 2011, http://deity.gov.in/sites/upload_files/dit/files/GSR315E_10511(1).pdf accessed on 11 September 2013.

[48] Freedom House, ‘Freedom on the net 2013’, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2013/india accessed on 4 October 2013.

21 Nov 2013 | Digital Freedom, India

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

Full report in PDF

(3) SURVEILLANCE, PRIVACY AND GOVERNMENT’S ACCESS TO INDIVIDUALS’ ONLINE DATA

Recent revelations in the Hindu have raised concerns over the extraordinary extent of domestic surveillance online, without any legal and procedural framework to protect privacy.[30] This chapter looks at how the Indian government’s surveillance and access to individuals’ online data presents a threat to freedom of expression. When people know or assume that governments or companies are monitoring their private communications, they are less inclined and less likely to communicate freely. The UN’s Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression Frank La Rue delivered a report to the Human Rights Council outlining how state and corporate surveillance undermine freedom of expression and privacy.[31] His report states that “Privacy and freedom of expression are interlinked and mutually dependent; an infringement upon one can be both the cause and consequence of an infringement upon the other.”

At the end of 2012, major telecom companies in India agreed to grant the government real-time interception capabilities for the country’s one million BlackBerry users. The Indian government has consistently requested that major web companies set up servers in India to allow them to monitor local communications.[32] Such surveillance capabilities potentially breach international human rights standards and have been subject to court challenges. In 1996, the Indian Supreme Court held that the citizen’s privacy has to be protected from abuse by the authorities.[33] Yet, Section 69 of the IT Act gives the state surveillance powers in the interest of national security or “friendly relations with foreign states”.[34]

In April 2013, India began implementing a $75 million Central Monitoring System (CMS) that will allow the government to access all digital communications and telecommunications in the country.[35] Content covered by the CMS will include all online activities, phone calls, text messages and even social media conversations. The scope of the programme, in development since 2009, is still to be determined, but some worry about the lack of safeguards against abuse in its implementation. Pranesh Prakash, Policy Director at the Centre for Internet and Society, argues: “In India, we have a strange mix of great amounts of transparency and very little accountability when it comes to surveillance and intelligence agencies.”[36]

Opponents of the system and human rights advocates worry the government will abuse the CMS to monitor or arrest political critics rather than to enhance national security as intended.[37] Arguably, CMS may violate Article 21 of the Constitution guaranteeing “personal liberty”. Concerns remain that without comprehensive privacy laws in India, the system will not be sufficiently accountable, and could chill free expression. Cynthia Wong, senior Internet researcher at Human Rights Watch, says: “The Indian government’s centralized monitoring is chilling, given its reckless and irresponsible use of the sedition and Internet laws. New surveillance capabilities have been used around the world to target critics, journalists, and human rights activists.”

In addition, new laws passed in April 2011 expanded internet surveillance in cybercafés, the primary point of access for the majority of Indians who cannot afford private computers or smartphones (see the section on access). Furthermore, Indians are required to register their real names to activate SIM cards and mobile and internet service providers (ISPs) are required to grant government authorities access to user data. Requesting user data becomes problematic when data is used for prosecuting free speech online and stifling political criticism (see section on criminalisation of online speech and social media).

India is one of the worst offenders globally both for takedown and for user requests, though on user information it is ranked after the US. The Google Transparency Report shows that India ranks second – after the United States – in the number of government requests for users data.[38] In August 2013, Facebook released a similar report. During the first six months of 2013, India ranks second in number of total requests (3,245 requests) and Facebook produced data in 50 percent of the cases.[39] It is possible that data requested by the government will be used in criminal prosecutions for defamation, hate speech, or harming “communal harmony”. This is problematic because these laws in themselves are too vague and broad and do not protect freedom of expression adequately, resulting in disproportionate arrests and prosecutions merely for the expression of views on a blog, liking a post on Facebook, or writing a political tweet. Without privacy law and safeguards to protect data, the collection and retention of such data can be misused and generate a chilling effect among the Indian population.

Many Indian MPs are aware of the need for a legal framework to protect the privacy of Indian citizens. In 2011, Parliament passed new data protection rules, but there is still no privacy law in India. Privacy is a fundamental human right and underpins human dignity and other key values such as freedom of association and freedom of expression. Key changes suggested by internet advocates include a Privacy Bill to address data protection and surveillance, and the establishment of a Privacy Commission.[40] It is time for the Indian government to take better account of the right to privacy and protection from arbitrary interference with one’s privacy.[41] Addressing mass surveillance and unwarranted digital intrusions in India are both necessary steps to fight self-censorship and promote freedom of expression.

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

This report was originally posted on 21 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[30] Shalini Singh, The Hindu, ‘India’s surveillance project may be as lethal as PRISM’ (21 June 2013), http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/indias-surveillance-project-may-be-as-lethal-as-prism/article4834619.ece accessed on 24 September 2013.

[31] Brian Pellot, Index on Censorship, ‘UN report slams government surveillance’, http://www.indexoncensorship.org/2013/06/government-surveillance-apple-google-verizon-facebook/ accessed on 10 September 2013.

[32] Firstpost, ‘Telecos agree to real-time intercept for Blackberry messages’ (31 December 2012), http://www.firstpost.com/tech/telecos-agree-to-real-time-intercept-for-blackberry-messages-573612.html accessed on 10 September 2013.

[33] Pranesh Prakash, New York Times, India Ink (blog), ‘How Surveillance Works In India’ (10 July 2013), http://india.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/07/10/how-surveillance-works-in-india/?_r=0 accessed on 10 September 2013.

[34] The Information Technology Act, Amendment, 2008, Section 69, ‘Directions of Controller to a subscriber to extend facilities to decrypt information’, http://cca.gov.in/cca/sites/default/files/files/itact-amendments2009.pdf accessed on 23 September 2013.

[35] Times of India, ‘Government can now snoop on your SMSs, online chats’ (7 May 2013), http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/tech/tech-news/internet/Government-can-now-snoop-on-your-SMSs-online-chats/articleshow/19932484.cms accessed on 5 September 2013.

[36] Pranesh Prakash, New York Times, India Ink (blog), ‘How Surveillance Works In India’ (10 July 2013), http://india.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/07/10/how-surveillance-works-in-india/?_r=0 accessed on 10 September 2013.

[37] Mahima Kaul, Index on Censorship, ‘India’s plan to monitor web raises concerns over privacy’, http://www.indexoncensorship.org/2013/05/indias-plan-to-monitor-web-raises-concerns-over-privacy/ accessed on 5 September 2013.

[38] Google, ‘Google Transparency Report’, http://www.google.com/transparencyreport/userdatarequests/IN/ accessed on 5 September 2013 and 15 November 2013.

[39] Facebook, ‘Global Government Requests Report’, https://www.facebook.com/about/government_requests accessed on 5 September 2013.

[40] In 2013, the Centre for Internet and Society drafted a Privacy Bill addressing data protection, surveillance and interception of communications. Centre for Internet and Society, ‘Privacy (Protection) Bill, 2013: Updated Third Draft’ (30 September 2013), http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/privacy-protection-bill-2013-updated-third-draft accessed on 4 October 2013.

[41] The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 12: “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.” http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/

21 Nov 2013 | Digital Freedom, India

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

Full report in PDF

(2) CRIMINALISATION OF ONLINE SPEECH AND SOCIAL MEDIA

The criminalisation of online speech in India is of concern as the authorities have prosecuted legitimate political comment online and personal views expressed on social media. New free speech opportunities offered by social media usage in India have been diminished after the introduction of provision 66A of the IT Act and the arrest of a number of Indian citizens for posting harmless content.[20] This chapter looks at how Section 66A constitutes a significant impediment to freedom of expression and will demonstrate the need to reform the law.

In 2011, Communications Minister Kapil Sibal asked Google, Facebook and Yahoo! to design a mechanism that would pre-filter inflammatory and religiously offensive content.[21] This request was not just, as noted at the time, technologically impossible, it was also a clear assault on free speech. The request demonstrated that even if Section 66A were reformed, further work would still be needed to prevent politically motivated crackdowns on social media usage.

Section 66A of the IT Act is both overly broad and also carries a disproportionate punishment. The section punishes the sending of “any information that is grossly offensive or has menacing character” or any information meant to cause annoyance, inconvenience, obstruction, insult, enmity, hatred or ill will, among other potential grievances. The provision carries a penalty of up to three years imprisonment and a fine.

IT (Amendment) Act 2008

66A: Any person who sends, by means of a computer resource or a communication device, —

(a) any information that is grossly offensive or has a menacing character; or

(b) any information which he knows to be false, but for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience, danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred or ill will, persistently by making use of such computer resource or a communication device; or

(c) any electronic mail or electronic mail message for the purpose of causing annoyance or inconvenience or to deceive or to mislead the addressee or recipient about the origin of such messages, shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years and with fine.

Much of the 2008 law historically stems from the 1935 UK Post Office (Amendment) Act, which related to telephone calls and telegraph messages. Rather than update the law to remove this dated provisions, the Indian government decided to extend them to new technologies.

Of particular concern is that there have been a number of arrests made under Section 66A for political criticism on Facebook, Twitter and even via private email. This is a worrying trend that may indicate an intolerance towards public interest speech about politicians that ought to be protected. Criminal and civil cases have also been brought against dozens of internet companies for failing to remove content deemed by some to be defamatory or religiously offensive.[22] Indians new to social media are learning to navigate the red lines of free speech or face prosecution. This degree of censorship is unwelcome in a functioning democracy.

For example, two women were arrested in 2012 for their use of Facebook, one for criticising disruptions in Mumbai during a politician’s funeral and the other for “liking” her friend’s comment (see case study). The two women were arrested under Section 66A and their arrest soon sparked public outrage, with the Times of India newspaper denouncing “a clear case of abuse of authority” by the police.[23]

Case study: Facebook arrests

On Sunday 18 November 2012, a 21-year-old Mumbai woman, Shaheen Dhada, shared her views on Facebook on the shutdown of the city as Shiv Sena chief Bal Thackeray’s funeral was being held. Her friend Renu Srinivasan “liked” her post. At 10.30 am the following day, they were both arrested and were ordered by a court to serve 14 days in jail. Hours later, they were eventually allowed out on bail after paying two bonds of Rs. 15,000 (£145) each.

Dhada had posted, “Respect is earned, not given and definitely not forced. Today Mumbai shuts down due to fear and not due to respect”. A local Shiv Sena leader filed a police complaint and Dhada and Srinivasan were booked under Section 295 A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) for “deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings or any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs.” Subsequently they were also charged under Section 505 (2) of the IPC for making “statements creating or promoting enmity, hatred or ill-will between classes”, and the police added Section 66A of the IT Act to the list of charges.

After a significant public outcry, charges were finally dropped. Other recent examples include a 19-year-old, Sunil Vishwakarma, who was detained for a derogatory Facebook post against a politician.[24] “We have received a complaint that he posted some objectionable comments against Raj Thackeray”, said an officer at Palghar police station. The police did not charge the teenager. He was questioned and later taken to a special cyber-crime cell before being released. In October 2012, Ravi Srinivasan, a 46-year-old businessman in the southern Indian city of Pondicherry, was arrested for a tweet criticising Karti Chidambaram, the son of Indian Finance Minister P Chadambaram. He was later released on bail.

Popular outrage over the police’s misuse of Section 66A led the Minister for Information and Communication Technology, Kapil Sibal, to issue a guidance to states on how to implement the controversial section of the IT Act.[25] However, there remain ongoing issues relating to political interference in law enforcement itself and to the vague wording of the law itself, with the use of the terms “annoyance” and “inconvenience” overly broad, giving the authorities a wide scope to criminalise comment and opinion.[26]

Despite top-down resistance to change, there is a push for reform of the law. Beyond the guidelines issued in late 2012 to prevent misuse of Section 66A, a revision of the law itself is still needed to prevent warrantless arrests and prosecutions. Civil society and political pressure to reform the law have recently increased. In 2012, cartoonist Aseem Trivedi and journalist Alok Dixit founded Save Your Voice, a movement against internet censorship in India that opposed the IT Act and demands democratic rules for the governance of internet.[27] The Minister for Information and Communication Technology has acknowledged there is an issue over the interpretation of 66A: “It’s very difficult to interpret the act on the ground. If you give this power to a sub-inspector of police, it is more than likely to be misused”.[28] Yet, he has defended the controversial law and resisted change, justifying his decision by saying that there was “no rampant misuse”.[29]

In January 2013, Rajeev Chandrasekhar, member of the upper house of the Indian Parliament, filed a petition to the Indian Supreme Court challenging Section 66A and the Information Technology [Intermediaries Guidelines] Rules for being “arbitrary and uncanalized, […] and in violation of the rights available to citizens under Articles 14, 19 and 21 of the Constitution.” Five other petitions related to the IT Act are currently under review by the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court has directed that pleadings will be listed before the Court in the first week of January 2014. This is a welcome step but the Supreme Court must deal with these cases as a matter of urgency and even in the case of success for the petitions, these decisions will require political will to be implemented.

The criminalisation of online speech and social media usage is a serious threat to freedom of expression in the country. The use of “offence” to silence political criticism online jeopardises free speech as a fundamental right necessary for public debate in a democracy. It is clear that there is the need and the public will to reform the law. The arrests and prosecution of citizens for innocuous messages has tarnished India’s image as the world’s largest democracy. While the 2014 General Elections offer a window of opportunity for change, the Indian authorities must undertake reform of the IT Act and end resistance to change.

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

This report was originally posted on 21 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[20] BBC News, ‘Outrage at India arrests over Facebook post’ (20 November 2012), http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-20405193 accessed on 5 September 2013.

[21] The Hindu, ‘Sibal warns social websites over objectionable content’ (6 December 2011), http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/sibal-warns-social-websites-over-objectionable-content/article2690084.ece accessed on 5 September 2013.

[22] Freedom House, ‘Freedom on the Net 2012: India’, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2012/india accessed on 9 September 2013.

[23] Times of India, ‘Shame: 2 girls arrested for harmless online comment’ (20 November 2012), http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2012-11-20/mumbai/35227016_1_police-station-shiv-sainiks-police-action accessed on 5 September 2013.

[24] Indian Express, ‘Now Palghar police detain 19-year-old for Facebook post on Raj Thackeray’ (28 November 2012), http://www.indianexpress.com/news/now-palghar-police-detain-19yrold-for-facebook-post-on-raj-thackeray/1037462/ accessed on 5 September 2013.

[25] New guidelines require that no less than a police officer of a rank of Deputy Commissioner of Police will be allowed to permit registration of a case under provisions of the Information Technology Act.

[26] Some provisions in Section 66A were purportedly drafted to prevent spam – messages typically sent in bulk and unsolicited.

[27] Save Your Voice, a movement against web censorship, http://www.saveyourvoice.in/p/about.html

[28] Lakshmi Chaudhry, First Post, ‘The real Sibal’s law: Resisting Section 66A is futile’, http://www.firstpost.com/politics/the-real-sibals-law-resisting-section-66a-is-futile-541045.html?utm_source=ref_article accessed on 18 November 2013.

[29] Nikhil Pahwa, Medianama, News and Analysis of Digital Media in India, ‘Sibal defends IT Act Section 66A in Parliament: Notes’, http://www.medianama.com/2012/12/223-sibal-defends-it-act-section-66a-in-parliament-notes/ accessed on 18 November 2013.