Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

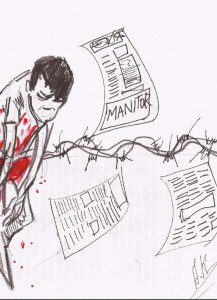

In the run up to today’s Azerbaijani presidential election, we publish an article and photographs from Index on Censorship magazine showing how the authorities have cracked down on journalists, activists and artists that criticize the government. These stories of the risks journalist and photographers face show how far the regime will go to silence its critics including intimidation and prison sentences. Writers Rasul Jafarov and Rebecca Vincent document the stories of some of the country’s courageous photojournalists, who have documented what life is really like under President Ilham Aliyev.

“In authoritarian regimes, art can serve as a powerful means of expressing criticism and dissent, subverting traditional means of censorship. Photography is particularly telling, capturing the raw truth and making it difficult for even seasoned propagandists to refute. These photographs, from Abbas Atilay, Shahla Sultanova, Mehman Huseynov, Aziz Karimov, Ahmed Muxtar and Jahangir Yusif, show a side of the capital Baku that contrasts sharply with the sleek, glossy image President Ilham Aliyev’s government seeks to portray. They expose an authoritarian regime prepared to arrest those who document protests and criticism — journalists, human rights defenders, civic and political activists and even ordinary citizens.

But those who embrace subjects others prefer to avoid, exposing unsavoury truths the Azerbaijani authorities would prefer to keep hidden — such as corruption and human rights abuses — do so at significant personal risk and hardship.

As journalists, they face intimidation, harassment, threats, blackmail, attacks and imprisonment in connection with their work, which is seen as direct criticism of the authorities. As artists, they face economic hardship and restrictions on where they can display and disseminate their work.

Most of these images were taken during unsanctioned protests in Baku. Photographers face particular hazards when covering protests in Azerbaijan, as not only can they be injured in the general chaos, but they can also be singled out because of their work. The Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety reports that so far in 2013 there have been 17 attacks against journalists and photographers covering protests.

Narimanov Park, Baku, 15 May 2010. Police forcibly detain a political activist during an unsanctioned protest. Photograph by Abbas Atilay

Fountain Square, Baku, 10 March 2013. A political activist during an unsanctioned demonstration protesting the deaths of military conscripts in non-combat situations. Authorities used excessive force to disperse the peaceful protest and detained more than 100 people. Photograph by Jahangir Yusif

Sabir Park, Baku, 11 March 2011. During an unsanctioned political protest

in the wake of the Arab Spring, a police officer encourages journalists to take his photo. This was a rare move, which the photographer believes was intended to distract photographers from other aspects of the protest, such as police physically restraining protesters. Photograph by Mehman Huseynov

Shamsi Badalbayli Street, Baku, 2 April 2012. A resident is forcibly evicted from the area where the Winter Garden will be constructed. Approximately 300 complaints have been sent to the European Court of Human Rights related to forced evictions from this area. Photograph by Ahmed Muxtar

Fountain Square, Baku, 20 October 2012. Police detain a young opposition activist during an unsanctioned protest calling for parliament to be dissolved after a video was released showing an MP discussing the sale of parliamentary seats. Dozens of activists were detained during that protest. Photograph by Aziz Karimov

Hijab ban, 5 October 2013. Photograph by Aziz Karimov

Investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova confronts police. Photograph by Mehman Huseynov

Nevreste Ibrahomova, head of Azerbaijan Islamic Party’s Women Council, holds the photo of an arrested Azerbaijani Islamist and chants freedom to him. Photograph by Shahla Sultanova

Photographers also face arrest and protracted legal action as a result of their work. Mehman Huseynov faces up to five years in prison on politically motivated hooliganism charges stemming from an altercation with a police officer during protests ahead of the Eurovision Song Contest in May 2012. The photographers featured in this story are among the few courageous individuals in Azerbaijan who remain willing to take on the risks associated with this work. They need international support and protection before they, too, become the subjects rather than the artists.”

Rasul Jafarov is the chairman of the Human Rights Club and project coordinator of the Art for Democracy Campaign. Rebecca Vincent is Art for Democracy’s advocacy director. She writes regularly on human rights issues in Azerbaijan

To find out more about the magazine and for subscription options, and read more about stories from the issue click here. These photographers will be part of an exhibition in London this winter. For more details, follow @art4democracy Join us to launch of Index on Censorship’s autumn issue on 15 October. To register for the event, click here.

Last week Azerbaijani journalist and Index award-winner Idrak Abbasov was brutally assaulted. As members of the international press apply for visas to cover the Eurovision Song Contest, local journalists continue to face attacks and intimidation. Celia Davies reports

The first photos of Idrak Abbasov were met with confusion and fear. The well-known Azerbaijani journalist was lying unconscious on the ground, his right eye swollen and black, his face bloodied. He was still wearing his luminous yellow press jacket. Later photos showed him in hospital, where he lay unconscious for close to six hours.

The first photos of Idrak Abbasov were met with confusion and fear. The well-known Azerbaijani journalist was lying unconscious on the ground, his right eye swollen and black, his face bloodied. He was still wearing his luminous yellow press jacket. Later photos showed him in hospital, where he lay unconscious for close to six hours.

Abbasov is still in hospital, suffering two broken ribs, three fractured ribs, cranial trauma, and damage to his right eye. One week on from his attack, his vision is blurred and the full extent of his head trauma remains unknown. He will not be discharged for at least another two weeks.

Less than a month ago, Abbasov was in London, collecting the Index on Censorship award for investigative journalism. Reflecting on the increasing restrictions on Azerbaijan’s struggling independent media, Idrak acknowledged that “For the sake of this right [to the truth] we accept that our lives are in danger, as are the lives of our families”.

On his return to Baku, he continued his work, heading out on 18 April to film the second round of demolition work in a residential area close to one of Baku’s numerous oilfields. Behind the demolition is the powerful state oil company SOCAR, which says the housing is illegal; the residents say they bought the land in good faith. When Abbasov began filming, SOCAR employees violently assaulted him. According to eyewitnesses the police looked on.

The other journalists at the demolitions, including Gunay Musayeva of Yeni Musavat newspaper and two cameramen for local media freedom NGO the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS), have spoken about the chaos at the scene. Musayeva was also attacked by guards but did not require hospitalisation; the taxi the cameramen arrived in had its windscreen broken, but the men inside were unhurt.

Abbasov was visited in hospital yesterday (25 April) by a group of SOCAR officials, who told him they would be leading an investigation into the incident – the Binagady Police Department has also launched a criminal case based on charges of hooliganism, to which Abbasov objects. “This wasn’t hooliganism; this is an Article 163 case, obstruction of the lawful activities of a journalist.”

A statement issued by the local EU delegation in response to Abbasov’s assault declared the incident “yet another example of unacceptable pressure [to which] journalists in Azerbaijan are exposed”.

This brutal attack comes as members of the international press are applying for visas to come to Baku for the upcoming Eurovision Song Contest in May. The Azerbaijani Prime Minister has promised Eurovision organisers that international journalists will be free to carry out their work; the day before the SOCAR incident, President Ilham Aliyev himself declared to the Cabinet of Ministers that freedom of expression in Azerbaijan is guaranteed.

The day after the incident, the Ministry of Internal Affairs released a statement reporting that “200-250 residents of the settlement beat and injured [SOCAR] employees”, naming Abbasov as “a local resident”. The Azerbaijani Human Rights Ombudsman also visited him in hospital, and has called for a full and objective investigation. In a separate press release, the Presidential Administration condemned the violence, but deemed it unrelated to Abbasov’s professional activity. The Department Chief there supported statements by SOCAR claiming that the journalists had not been wearing press jackets – in the face of photo evidence to the contrary – and finished with a warning to media representatives: “journalists covering such actions must wear special clothes, [and] must not interfere in the process.”

Amidst these competing versions of events, the president’s confident assurances remain largely at odds with an often hostile reality, and international journalists are advised to be vigilant about their personal security, as well as the safety of any local staff – fixers, drivers, and so on – with whom they are working.

When asked, Abbasov said that his attack should not deter the international media from covering the event. Emin Huseynov, Chairman of IRFS, one of Abbasov’s employers, echoed his advice:

Write about Eurovision. But be aware there is a darker, sadder story behind the shiny buildings and expensive shops that will continue when the singing is over.

With seven journalists already in jail and the dust only just settling following the high profile attempted blackmail of leading investigative reporter Khadija Ismayilova, independent media outlets and NGOs are starting to worry about what will happen after Eurovision, once Azerbaijan is no longer under the international spotlight. Many fear that there will be a backlash against all those who have spoken out against human rights and free expression violations – and that once Eurovision is over, Azerbaijan will drop off the international agenda.

Celia Davies is Program Development Manager at the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety in Baku, Azerbaijan

As the international community looks forward to the Eurovision Song Contest, Azerbaijan is working hard to present itself as a modern, democratic country. But a new report from Index and partners paints a very different picture

As the international community looks forward to the Eurovision Song Contest, Azerbaijan is working hard to present itself as a modern, democratic country. But a new report from Index and partners paints a very different picture