29 Jan 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News, United Kingdom

Sometimes, when I’m bored, or a bit down and feel the need to believe there are people in the world who are worse to me (worse, not worse off), I turn to TripAdvisor.

I’m sure there are perfectly reasonable people on TripAdvisor. Perfectly normal people, who may have enjoyed a dinner somewhere, or made friends with the barman at their holiday hotel, and thought “I must tell the world! These hardworking service industry people deserve my support.” I’m sure there’s lots of that going on on TripAdvisor (other review sites are available).

These happy people do not concern me. No, these are not the reviews I want to read. I seek out the one and two stars which are often written by the worst people in the world.

Petty, greedy, stingy, paranoid and usually convinced of their own way with imagery. Imagine eating out with these people.

The waitress approaches, smiling (as they often do):

“Would you like to see the wine list?”

“Yes please.” (List is delivered. Exit waitress).

“What do you think she meant by that?”

“What?”

“Asking if we wanted the wine list like that.”

“Like what?”

“Didn’t you hear her?”

“Yes. She said ‘Would you like to see the wine list?’ They often do.”

“But it was the waaaayyyy she said it.”

“Uh.” (Scans room for exits, sees only cheery floor staff).

On goes the evening. Everything is noted. The wine is too cold, the food too hot. Side orders are too expensive, there’s a draft only your dining partner can perceive. The service is too slow/fast. Somehow, in spite of it being a busy night, the waitress has been giving your companion a Paddington hard stare all night.

No, you certainly will not be having dessert, not at these prices.

The bill arrives, and is divided down to the last pea (“You got more ice in your tap water than I did”).

You depart, he on his bus, you on yours. On his way home, he cancels his debit card because he’s sure the restaurant people will have cloned it. You reach home and climb into bed, despondent. His fun though, has just begun.

Pouring himself a decent measure of the large whisky he hides when visitors are around, he settles on the sofa and logs into TripAdvisor (other review sites etc).

“Our trouble started,” he types. “When my friend called to book the table.” (You are now implicated).

“Having read my neighbour Giles Coren’s fine review in the Times of London, I was expecting high things of Brasserie Sarkozy. Methinks Coren the Younger’s judgement may have been clouded by one too many stiffeners over lunch, perhaps with his delightful sister, Victoria (with whom I would be only too happy to ‘Only Connect’!)…”

Why are you friends with this person again? On he goes. The broccoli was insufficiently purple. The steak (always steak) was “inferior” to the Specially Selected 30 Day Matured Aberdeen Angus Sirloin you get in Aldi for just £5.99. The staff were too casual, the room too stuffy, the building in the wrong neighbourhood… And the prices? Is this Monte Carlo?

And he wouldn’t have minded that much if it wasn’t for the rat he almost certainly saw in the gents.

Your friend clicks “one star” closes down his computer, and heads for bed, to dream of the panic when the restaurant’s owners (shysters and rip-off merchants every last one of them) discover his latest mighty internet onslaught.

One wonders if your friend (let’s call him gourmand_Gareth, as that’s what he calls himself), drunk on power, has considered the consequences. Particularly the consequences of the claim about the rat in the toilets, which, while he didn’t quite intentionally make up, is a bit of a misreport. Specifically, he’s moved the rat’s location from “in his imagination” to “standing on the cistern, singing Blur’s classic Britpop ballad To The End”. It didn’t happen. It is wrong to publish a review saying it did. It’s quite probably libellous. In fact, the chef is on the phone to his lawyer right now.

I don’t like your friend (I suspect you don’t either, but you’ve known him since school when… Actually you didn’t like him then either, did you?), but I don’t want him to end up in trouble.

But this is what could happen. While there’s only ever been one successful libel case against a restaurant reviewer in the United Kingdom (Goodfellas v Irish News, 2007, overturned on appeal, fact fans), there has been a rise in libel cases involving social media and the web. According to the Independent, there was a 300 per cent increase between 2012-13 and 2013-14 alone.

In spite of the work done by Index on Censorship and others in improving England’s libel laws, being sued — even being threatened with libel action — is still a deeply unpleasant experience, and quite possibly an expensive one too. Meanwhile, continued threats to the concept of the “mere platform” (that is to say, a site such as TripAdvisor, which allows people to post content without pre-moderation, should not be held legally liable) face threats from the actions of Max Mosley and others who are determined that the web be a more tightly controlled space.

Pre-moderation (editing, in effect) is anathema to how we use the web every day. Try to imagine having to send every tweet to some poor bugger in an office in Dublin who then has to decide whether it gets past every single restriction on speech in the European Union before he publishes it to your page. Not going to happen, no matter how many European courts believe it should.

But on the other side of the coin, people like your friend Gareth should at the very least be aware of what the laws are, and what risks they run. The past few years have seen countless cases of people facing civil and criminal sanction for tweets where they clearly had no idea what the law was (*innocent face*). This is not a plea for more laws, or even more self-censorship. But one does wonder if basic education in what the potential pitfalls of online interaction are, is necessary. Index and its partners are bringing out guides for artists to free speech and the law, but what about the rest of us? It’s too late for poor, silly Gareth.

This article was posted on January 29 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Nov 2014 | China, News, Tibet

![Photo: Wolfgang H. Wögerer, Vienna, Austria [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Vienna_2012-05-26_-_Europe_for_Tibet_Solidarity_Rally_158_Lobsang_Sangay.jpg)

Lobsang Sangay at a solidarity rally for Tibet in 2012 (Photo: Wolfgang H. Wögerer, Vienna, Austria [CC-BY-SA-3.0 or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

It was not, to say the least, what he had been expecting. Just a few weeks earlier, Sangay had become Tibet’s new political leader, taking over all political authority from the Dalai Lama after winning an election held among exiled Tibetans all across the world. It had been his first day in parliament in Dharamsala, where the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA) is based, and his entire cabinet had just been unanimously approved — a cause for celebration.

Yet that same day, a top-secret memo about an upcoming visit to the US had somehow been obtained from the government’s computers, and leaked into the public domain. “Everything was supposed to be very confidential, and the memo was only meant for three people in Washington DC,” Sangay tells Pao-Pao.

His assistants recommended cancelling the trip altogether. “It’s all out,” they told Sangay. “Nothing is a secret.” Their worries were not unwarranted. The Chinese government had started pressuring the American politicians listed in the memo to cancel their meeting with Sangay. Still, he pushed ahead. “I said: ‘We are going to Washington DC, on the same dates as described in the memo, and we are meeting with the same people as in the memo. That’s the only way we can respond to Beijing’s bullying.’”

Security upgrade

In the end, the visit went ahead as planned. But the attack was a shock to Sangay. “First of all, that Beijing is so capable of penetrating our computers that they can get at even our very confidential memos,” he says. “But also, that when I came back to the office, they were logging into every computer in the office and trying to shut it down, trying to track down which computer was affected with a virus and how they stole the secret memo. The whole place was shut down.”

It wasn’t the first time that the Tibetan administration had found itself under Chinese cyber attack. In 2008, the large-scale cyber spying operation Ghostnet managed to extract emails and other data from the CTA. Ghostnet also affected other Tibet-related organisations, as well as embassies and government organisations across the world. A year later, ShadowNet was employed, which researchers from the Infowar Monitor (IWM) at the University of Toronto called a form of “cyber espionage 2.0”.

The IWM researchers were able to establish that the hackers worked from within China, but they have been hesitant to link these hackers to the Chinese government due to a lack of direct evidence. However, an American cable released by Wikileaks describes a “sensitive report” that was able to establish a connection between the attackers’ location and the Chinese army.

The 2011 attack propelled Sangay to tighten the administration’s digital security. “At the time, there was a different mindset about it: ‘Oh, we can’t do much about it, Beijing can do whatever it wants,’” he recalls. Sangay, who was an outsider to Tibetan politics and had spent the sixteen years before he was elected at Harvard Law School, didn’t agree. “I thought that we could upgrade our security to a certain level. Now, even if we have a virus, it’s only on one computer, we can isolate it.”

But while the CTA’s office might no longer grind to a halt when a computer is infected, attacks have continued unabated. In 2012, a Chinese cyber attack infiltrated at least 30 computer systems of Tibetan advocacy groups for over ten months. In 2013, the CTA’s website Tibet.net was compromised in a so-called watering hole attack, which allows hackers to spy on and subsequently attack website visitors.

Greg Walton, an internet security researcher at Oxford University, is concerned at the growing number of these watering hole attacks. When they are combined with attacks that exploit software vulnerabilities, he argues that “there is essentially no defence for the end user, and no amount of awareness or training will mitigate the threat.”

Sangay does not believe that absolute security is possible. “Beijing is still, I am sure, trying to steal things. And I am sure they are successful, in some sense. But we also have to try to make it a little more difficult,” he says. “I assume my email is being read on a daily basis. The Pentagon, the CIA, multinational companies are all being hacked, and they are spending hundreds of millions to protect themselves.”

Sangay throws up his hands: “Poor me! My administration’s budget is around 50 plus million dollars. Even if I would spend my whole budget to protect my email account, that still wouldn’t be enough.”

No attachment, please

Sangay does believe that many problems can be avoided with a few basic precautions. He uses very long passwords for instance, and changes them often to prevent hacks of his own email account. And, he says: “You always have to follow Buddha’s message. What would Buddha say if you send him an email? ‘No attachment please!’” Sangay laughs. “One of the cardinal sins in Buddhism is attachment. Well, Buddha’s lessons, who said that 2,500 years ago, are still valid.”

Holding himself to “Buddha’s teachings” has prevented Sangay from getting his computer infected many times — although there have been some close calls. Take for example the time Time magazine’s editor Hanna Beech emailed him, a week prior to a scheduled interview in Dharamsala.

“She sent me the ten questions she would ask me. I found that very generous, journalists sending me questions ahead of time!” Sangay was about to download the attachment — but then he paused. “I grew a bit suspicious, so I decided to write back to her to ask if it was really her.” Beech said it wasn’t.

The attack was sophisticated, but not uncommon, Sangay says. “We get that on a daily basis, literally; some Tibetan support group or someone from our office sends an email that will contain a virus.”

Strengthening bonds

For the Tibetan government, digital communications have offered Chinese hackers a welcome point of attack. But Sangay also emphasises the positive sides of the internet: “Despite the [Great] Firewall, information breaks through, and is exchanged. That is happening, and that is not something that the Chinese government or any other government can prevent.”

He points to the 2008 protests in Tibet as one example. In the protests, which some dubbed “the cellphone revolution”, written reports, videos and photos from eyewitnesses were able to make their way to the rest of the world via mobile phones.

Additionally, the internet has allowed the Tibetan Central Administration in Dharamsala, home of about 100,000 Tibetans, to strengthen its bonds with the approximately 50,000 exiled Tibetans living elsewhere. Sangay says that the exile community — “scattered across some forty countries” — keeps in touch mainly through the internet.

“The internet has been very vital. The other day, I was speaking to Tibetans in Belgium. I asked them how many log in to Tibet.net, our website, and how many watch Tibetan online TV. About 40% raised their hands.” Tibetans from inside Tibet even manage to send Sangay “one-off messages” via Facebook from time to time. “Things like: ‘I wish you well’, from Facebook accounts that are immediately deleted.”

Dangerous, but helpful

Tibetans inside and outside of China now also communicate constantly via WeChat, but that is not without danger. A year ago, two monks in Tibet were arrested and jailed after posting pictures of self-immolations via the chat app. “Many say it’s very dangerous, because it’s an app by a Chinese company,” Sangay concedes. Still, he also considers it “very helpful and informative” as long as it is used to discuss safe topics.

The Tibetan administration consciously abstains from contacting Tibetans inside China “for fear that we might jeopardise them,” Sangay says. “We get a little less than 100,000 readers to our website every month, and we know many are from inside Tibet and China as well. We know it’s happening, but we really don’t make deliberate efforts [to contact them], and we also don’t keep track.”

Skyping with Woeser

Since Sangay was elected, it has been too risky for him to keep in touch with Tibetans in China via the internet. But before his election, like many others, he was in touch with those inside China almost every day. During his years at Harvard, he often Skyped with the famed Tibetan blogger and activist Tsering Woeser.

“It almost became an everyday ritual. I would go to the office, and then at a particular time I would log on and we would talk for half hour or more. Because her Tibetan wasn’t good, I became her unpaid, amateur Tibetan language teacher.” Sangay laughs as he recalls Woeser’s unsuccessful attempts to crack jokes in her — at the time — mediocre Tibetan.

Unfortunately, Sangay says he “had to stop talking to her for fear that I might endanger her”. But he still admires her work: “She is a good source of information. She compiles information from inside and shares with the rest of the world. She is very bold.” He considers bloggers like her an invaluable resource for those who want to know what life in Tibet is really like.

So will the internet ultimately be a force for good or evil? Sangay doesn’t know. “It all depends on who uses it. For good, if more good people use it.” On the one hand, he is in awe at how nowadays “in zero seconds, at almost zero cost, you can send vast volumes of information”. But he worries about the security side of the internet. “Ultimately, the [power] dynamic is so asymmetrical. One has wealth, and control over access to stronger and better technology, and one doesn’t.”

That, of course, is a power dynamic that the Tibetan leader has long ago gotten accustomed to. “I think the David and Goliath battle will go on, even on the internet,” Sangay says. “Ultimately, if David will prevail, we will have to see.”

This article is also available in Chinese at Pao-Pao.net

This article was posted on 10 November at indexoncensorship.org with permission from Pao-Pao.net

12 Jun 2014 | Cameroon, Iran, News, Nigeria, Russia

The 2014 World Cup in Brazil starts today, 32 nations preparing to battle it out across eight groups in the first stage of the tournament.

This year’s competition, like so many before it, comes with its designated group of death. For those not familiar with the lingo, it means the group containing the highest amount of strong teams. Or even more simply put, the group most difficult to progress from. (You can’t accuse the beautiful game of holding back on the melodrama).

Index has looked at the countries taking part in arguably the biggest show on earth, and put together our own group of death — the freedom of expression edition.

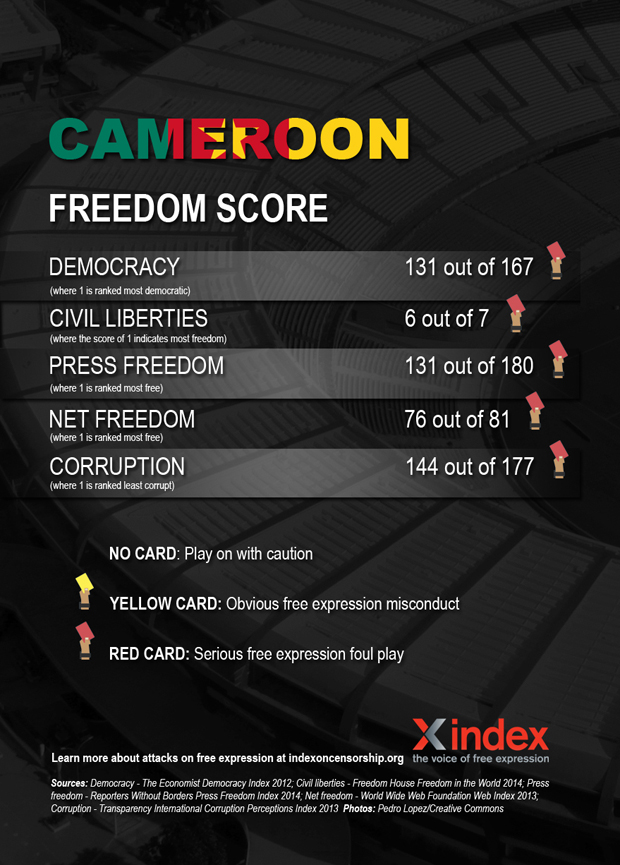

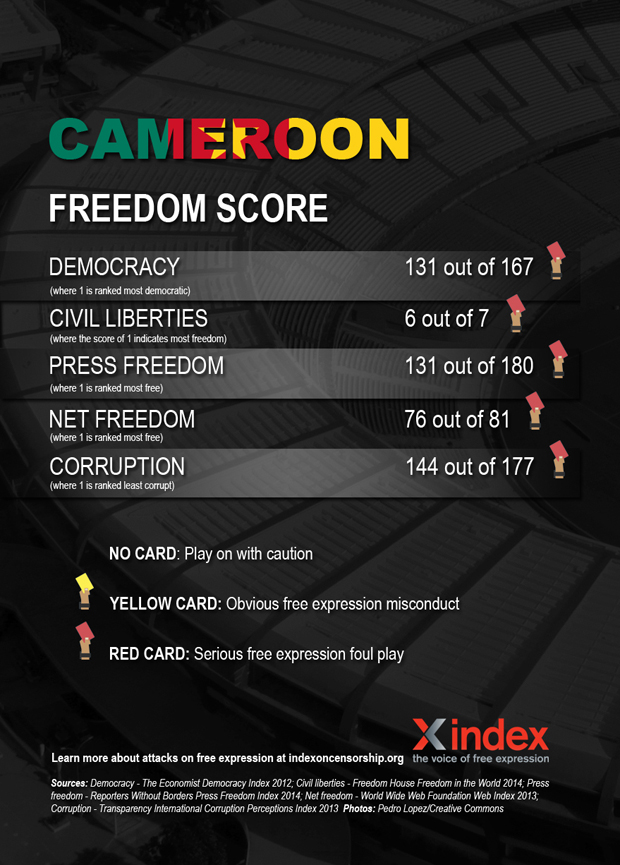

Cameroon

Cameroon — or the Indomitable Lions — have a solid track record in qualifying for the World Cup, having taken part seven time, more than any other African side. There were also the first African team to make it to the quarter final and are responsible for one of the most iconic moments in the tournament’s history. Their track record on free speech, however, is less impressive.

Freedom of expression is guaranteed in Cameroon’s constitution. Despite this, the government of Paul Biya — the country’s leader since 1982 — has been been accused numerous violations of free expression.

Large parts of the press are biased towards the ruling elite, while critical journalists face detainment, harassment and demands to reveal sources, among other things. Self censorship is widespread. In September 2013, 11 press outlets, including newspapers, radio stations and a TV station, were shut down for disrespecting “ethics and professional norms”. In 2010, former newspaper editor Germain Ngota, who had been investigating corruption allegations involving the state-run oil company, died in jail.

Freedom of assembly is often cracked down on. In 2012, former opposition presidential candidate Vincent-Sosthène Fouda and others were charged with “holding an unlawful demonstration”. The same year, security forces used tear against a crowd gathered to protest against Biya. In 2008, around 100 people were killed in clashes with police in anti-government riots.

Arts are not spared either. In 2013, Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s film Le President was banned in Cameroon because it discussed the end of Biya’s reign . In 2008, Lapiro de Mbanga, who criticised the constitutional change in term times that would allow Biya to stay in powers through song, was arrested.

Homosexuality is outlawed, and punishable by up to 14 years in prison. Human rights violations against LGBTI people, or those perceived to be, are “commonplace”. In July 2013, Eric Ohena Lembembe, director of the Cameroonian Foundation for AIDS (CAMFAIDS) was brutally murdered, in what friends suspect was an attack based on his pro-LGBTI advocacy.

Iran

Team Melli will hope that their fourth appearance at the World Cup will see them progress from the group stages for the first time. When he was elected almost a year ago, there was hope that President Hassan Rouhani would be a progressive force within Iran. The results so far have been mixed.

Since coming into power, Rouhani has taken some steps to improve press freedom, such as withdrawing 50 motions against journalists, and lifting some restrictions on previously banned topics. However, the government still controls all TV and radio, and censorship and self-censorship is widespread. The latest figures put the number of jailed journalists in Iran at 35. In January 2013, a group of journalists were arrested for allegedly cooperating with “anti revolutionary” news outlets abroad. Journalists’ associations and civil society organisations that support freedom of expression have also been targeted.

The internet and social media played a significant part in publicising and documenting the protests that followed the 2009 election, which many Iranians believed was fraudulent. The regime has banned Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and, recently, Instagram. The lead-up to the 2013 elections saw Iranian leaders tightening access to the web, and silencing “negative” news. While Rouhani — seemingly an avid Twitter user — has indicated plans to relax web censorship, the country’s plans to launch a “national internet” are said to be going ahead.

In May, eight people were jailed on charges including blasphemy, propaganda against the ruling system, spreading lies insulting the country’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on Facebook. Recently, a group of young people were arrested over a video posted of them singing and dancing along to the song “Happy”, which police called was a “vulgar clip” that had “hurt public chastity”. Some commentators believe the move was meant to intimidate Iranians and discourage online criticism.

Nigeria

Brazil 2014 marks 20 years since Nigeria’s first outing at the World Cup, and the Super Eagles arrive at the tournament as reigning Africa Cup of Nations champions. The country’s leadership, however, is not a champion of free expression.

While parts of Nigerian media is controlled by people directly involved in politics, the country can also boast a lively independent media sector. However, journalists, especially those covering sensitive topics such as corruption or separatist and communal violence still face threats. Journalists have been arrested by security forces, and media outlets have been attacked by terrorists. Legal provisions such as sedition and criminal defamation also challenge press freedom. In 2011, a journalist was arrested over stories detailing alleged corruption in the Nigerian Football Federation.

The country’s freedom of information act was put in place in 2011. However, when human rights lawyer Rommy Mom tried to use the legislation to trace some 500 million of missing aid money allocated to his flood ravaged home state of Benue, he was met with threats from people connected to the state governor, and was forced to flee.

The Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act 2013 outlawing gay marriage and relationships, was signed into law by President Goodluck Jonathan in January. The unpublished law makes it illegal for gay people to hold meetings, and outlaws the registration of homosexual clubs, organisations and associations. Those found to be participating in such acts face up to 14 years in jail.

Nigeria has come under international attention in recent months for abduction of the Chibok school girls by terrorist group Boko Haram. Among other things, Nigerians responded with the powerful #BringBackOurGirls campaign. In June however, authorities seemed to ban an offline protest against the kidnappings, before quickly backtracking. It is also worth noting that the Nigerian government has targeted journalists in their “war on terror”.

Russia

Team Sbornaya travel to Brazil in the knowledge that next time in the World Cup rolls around, they will be playing on home soil. Russia of course, recently hosted another international sporting event — the 2014 Winter Olympics. However, global attention did not improve the country’s poor record on freedom of expression. In fact, experts predicted a rise in censorship ahead of the Olympics.

Press freedom has long been under attack by Russian authorities, with TV news currently providing little beyond the official government line. In the last few months, the relatively well-respected TV channel RIA Novosti was liquidated following a decree by President Vladimir Putin, and replaced by a new press agency headed by a Kremlin-loyalist. In January, Dozhd, a popular independent TV channel was dropped by satellite and cable operators over a controversial survey. For the remaining critical journalists, Russia — one of the countries with the highest number of unpunished journalist murders — is a dangerous place to work.

The crackdown on the internet is widely believed to have started with the protests surrounding the elections securing Putin’s third term in power, organised partly through social media, but it has recently intensified. The Duma has adopted controversial amendments to an information law, targeting bloggers with blocking and fines for anything from failing to verify information posted, to using curse words. Also recently, the founder of “Russian Facebook” VKontakte says he was forced out, with the son of the head of Russia’s largest state-run media corporation predicted to take over as CEO. In 2013, the Duma approved legislation allowing immediate blocking of websites featuring content deemed “extremist”.

Public protests are discouraged through forceful responses by police, arrests, harsh fines and prison sentences. The country’s recent anti-gay legislation also pose a big threat to free expression and assembly. The ban on “promotion” of gay relationships, means that any form of expression deemed to be “gay propaganda” can be shut down. The law has also lead to physical attacks on Russia’s LGBT population.

An earlier version of this article stated that Brazil 2014 marks ten years since Nigeria’s first outing at the World Cup. This has been corrected.

This article was published on June 12, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Jun 2014 | Americas, Brazil, Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Reports, Index Reports, News

World Cup host country Brazil has the potential to become an influential, global leader in digital rights — but that will depend on key decisions taken in the coming months, Index on Censorship says in a report published today.

The internet has provided new opportunities for free expression in the country, but attempts to regulate content, inequality in access to the internet and violence against journalists, are among the challenges to internet freedom that remain in Brazil.

“With the adoption of a progressive legislation on internet rights, Brazil is taking the lead in digital freedom,” said Melody Patry, Index’s Senior Advocacy Officer and author of the report Brazil: A new global internet referee? “Digital technologies have provided new opportunities for freedom of expression in the country, but have also come with new attempts to regulate content and strong inequalities between those with and without access to the internet. Old problems like violence against journalists, media concentration and the influence of local political leaders over judges and other public agents persist,” she said. Brazil recently signed into law the Marco Civil bill, known as the internet bill of rights. It will provide a much-needed legal framework for internet rights, while also making Brazil the largest country in the world to enshrine net neutrality in its legal code. The law also includes stricter privacy standards to fight surveillance, and guarantees freedom of expression online. However, the country still faces considerable challenges in ensuring it can deliver on the promise of the new legislation.

The report is available in English and Portuguese. This article was published on June 9, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

![Photo: Wolfgang H. Wögerer, Vienna, Austria [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Vienna_2012-05-26_-_Europe_for_Tibet_Solidarity_Rally_158_Lobsang_Sangay.jpg)