30 May 2017 | Campaigns -- Featured, Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Statements, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

On 16 May the Venezuelan government issued Executive Order 2489 to extend the “state of emergency” in Venezuela, in place since May 2016. This new extension authorises internet policing and content filtering. This measure deepens the restrictions to the free flow of information online even more. They include the blocking of streaming news outlets, such as VivoPlay, VPITV, and CapitolioTV. Other serious practices that prevail in Venezuela are the aggressions of military and police personnel to journalists and civilian reporters, and the detention of citizens in the wake of content published on social networks.

This happens in a context of a general deterioration of telecommunications, as a consequence of the divestment in the sector in the last 10 years. This has turned Venezuela into the country with the worst internet connection quality in the Latin American region. Given the censorship practices applied to traditional media, the internet has become an essential tool for the freedom of expression and access to information of the Venezuelan people.

The measures taken by the Venezuelan Government to restrict online content constitute restrictions to the fundamental rights of Venezuelan citizens and, as such, do not comply with the minimum requirements of proportionality, legality, and suitability. The Venezuelan Government has systematically ignored civil society requests regarding the total number of blocked websites. To this date, there is evidence of the blocking of 41 websites, but it is suspected that many more websites are being blocked. The legal and technical processes applied by the government to determine and execute the blocking of websites remain unknown.

These kinds of practices affect the exercise of human rights. In a joint release, the rapporteurs for freedom of expression of the UN and the IACHR condemned the “censorship and blocking of information both in traditional media and on the internet”. During the last few months, three streaming tv providers have been blocked without a previous court order. Moreover, the Government has used unregulated surveillance technologies that affect the fundamental rights of citizens, such as surveillance drones to track and watch demonstrators, while at the same time expanding its internet surveillance prerogatives, through the creation of bodies such as CESPPA.

In addition to this, the government has implemented mechanisms for the collection of biometric data without citizens being able to determine their purpose nor who has access to such information. The official discourse towards the internet, and specifically to social networks, is disturbing: the director of the National Telecommunications Commission has recently declared that social networks are “dangerous” and a tool for “non-conventional war”.

The sum of this factors, aggravated by the passage of time and the deepening of the social and political crisis, outlines the creation of a state of censorship, control, and surveillance that gravely affects the exercise of human rights. Quality access to a free and neutral internet is recognised internationally as a necessary condition for the exercise of freedom expression, communication and the access to information, and as a precondition of the existence of a democratic society. In that regard, the undersigned civil society and academic organisations wish to set our position in the following terms:

We express our condemnation to the extension of the state of exception in Venezuela, as well as to the restrictions to the free flow of online content that derive from it.

We manifest our concern for the growing deterioration of internet access infrastructure and telecommunications in Venezuela. The maintenance of such systems is of vital importance for education, innovation, and the communication of Venezuelans.

We emphasise that the use and implementation of technological tools such as drones and biometric identification systems must fit human rights standards and not affect the fundamental freedoms of citizens, in particular their privacy and autonomy.

We insist that all measures that restrict the free exercise of fundamental rights, such as the blocking of web pages, must comply with the minimum requisites of proportionality, legality and suitability, and in consequence, must be only adopted by judicial authorities following a due process.

We request the ending of the harassing actions and insulting speech conducted by public servants online against NGOs and human rights activists that document and denounce acts through digital platforms.

We demand the cessation of military and police aggressions against journalists and citizen reporters.

We request transparency on the actions taken to restrict internet traffic and content and demand an answer to the requests for public information made by civil society regarding the practices of content blocking and filtering executed by the public administration.

Signed,

Derechos Digitales

Instituto Prensa y Sociedad de Venezuela

Acceso Libre (Venezuela)

(DTES-ULA) Dirección de Telecomunicaciones y Servicios de la Universidad de los Andes

Venezuela Inteligente

Public Knowledge

Access Now

Espacio Público (Venezuela)

Hiperderecho (Perú)

Son Tus Datos (México)

Alfa-Redi (Perú)

Centro de Derechos Humanos de la Universidad Católica Andrés Bello

EXCUBITUS Derechos Humanos en Educación

IPANDETEC (Panamá)

Sursiendo, comunicación y cultura digital

Red en defensa de los derechos digitales, R3D

Global Voices Advox

Asuntos del Sur

Internet Sans Frontières (Internet Without Borders)

Center for Media Research – Nepal

Index on Censorship[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1496155906014-ceb40fec-308b-10″ taxonomies=”13, 6914″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

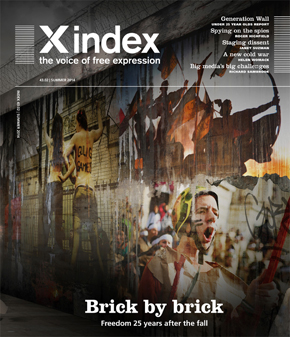

11 Oct 2016 | Digital Freedom, Magazine, Volume 45.03 Autumn 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

CREDIT: ra2studio / Shutterstock

Securing your connection

Activists in countries where the web is heavily censored and internet traffic is closely monitored know that using a virtual private network or VPN is essential for remaining invisible.

A VPN is like a pair of curtains on a house: people know you are in but cannot see what you are doing. This is achieved by creating an encrypted tunnel via a private host, often in another country, through which your internet data flows. This means that anyone monitoring web traffic to find out persons of interest is unable to do so. However, the very fact that you are using a VPN may raise eyebrows.

An increasing number of VPNs promise truly anonymous access and do not log any of your activity, such as ExpressVPN and Anonymizer. However, access to some VPN providers is blocked in some countries and their accessibility is always changeable.

Know your onions

One of the internet’s strengths is also one of its weaknesses, at least as far as privacy is concerned. Traffic passes over the internet in data packets, each of which may take a different route between sender and recipient, hopping between computer nodes along the way. This makes the network resilient to physical attack – since there is no fixed connection between the endpoints – but also helps to identify the sender. Packets contain information on both the sender’s and recipient’s IP address so if you need anonymity, this is a fatal flaw.

“Onion” routing offers more privacy. In this, data packets are wrapped in layers of encryption, similar to the layers of an onion. At each node, a layer of encryption is removed, revealing where the packet is to go next, the benefit being that the node only knows the address details of the preceding and succeeding nodes and not the entire chain.

Using onion routing is not as complicated as it may sound. In the mid-1990s, US naval researchers created a browser called TOR, short for The Onion Routing project, based on the concept and offered it to anyone under a free licence.

Accessing the dark web with the Tor browser is a powerful method of hiding identity but is not foolproof. There are a number of documented techniques for exploiting weaknesses and some people believe that some security agencies use these to monitor traffic.

Put the trackers off your scent

Every time you visit a popular website, traces of your activity are carefully collected and sifted, often by snippets of code that come from other parts of the web. A browser add-on called Ghostery (ghostery.com) can show you just how prevalent this is. Firing up Ghostery on a recent visit to The Los Angeles Times website turned up 102 snippets of code designed to track web activity, ranging from well-known names such as Facebook and Google but also lesser known names such as Audience Science and Criteo.

While some of this tracking has legitimate uses, such as to personalise what you see on a site or to tailor the ads that appear, some trackers, particularly in countries where there are lax or no rules about such things, are working hard to identify you.

The problem is that trackers can work out who you are by jigsaw identification. Imagine you have visited a few places on the web, including reading an online article in a banned publication and then flicking through a controversial discussion forum. A third-party tracker used for serving ads can now learn about this behaviour. If you then subsequently log into another site, such as a social network, that includes your identity, this information can suddenly be linked together. Open-source browser extensions such as Disconnect (disconnect.me) offer a way to disable such trackers.

Use the secure web

A growing number of popular websites force visitors to connect to them securely. You can tell which ones because their addresses begin with https rather than http. Using https means that the website you are visiting will be authenticated and that your communications with the site are encrypted, stopping so-called man-in-the-middle attacks – where a malicious person sits between two people who believe they are communicating directly with each other and alters what is being communicated. Google, as well as using https for both Gmail and search, is also encouraging other websites to adopt it by boosting such sites up the search rankings.

Rather than remembering to check you are using https all the time, some people employ a browser extension created by the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the Tor Project called HTTPS Everywhere to do it for them. It is available for Chrome, Firefox and Opera and forces browsers to user https versions of sites where available.

Hide your fingerprints

Traditional identification methods on the web rely on things like IP addresses and cookies, but some organisations employ far more sophisticated techniques, such as browser fingerprinting. When you visit a site, the browser may share information on your default language and any add-ons and fonts you have installed. This may sound innocuous, but this combination of settings may be unique to you and, while not letting others know who you are, can be used to associate your web history with your browser’s fingerprint. You can see how poorly you are protected by visiting panopticlick.eff.org.

One way to try to avoid this is to use a commonly used browser set-up, such as Chrome running on Windows 10 and only common add-ins activated and the default range of fonts. Turning off Javascript can also help but also makes many sites unusable. You can also install the EFF’s Privacy Badger browser add-on to thwart invisible trackers.

Mark Frary is a journalist and co-author of You Call This The Future?: The Greatest Inventions Sci-Fi Imagined and Science Promised (Chicago Review Press, 2008)

This article is from the Autumn issue of Index on Censorship Magazine. You can order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”90642″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064220008536724″][vc_custom_heading text=”Anonymous now” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064220008536724|||”][vc_column_text]

May 2000

Surfing through cyberspace leaves a trail of clues to your identity. Online privacy can be had but it doesn’t come easy, reports Yaman Akdeniz.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89179″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064220701738651″][vc_custom_heading text=”Evasion tactics” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064220701738651|||”][vc_column_text]

November 2007

Nart Villeneuve provides an overview of how journalists and bloggers around the world are protecting themselves from censorship.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89164″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422010363345″][vc_custom_heading text=”Tools of the trade” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422010363345|||”][vc_column_text]

March 2010

As filtering becomes increasingly commonplace, Roger Dingledine reviews the options for beating online censorship.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The unnamed” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2016 Index on Censorship magazine explores topics on anonymity through a range of in-depth features, interviews and illustrations from around the world.

With: Valerie Plame Wilson, Ananya Azad, Hilary Mantel[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80570″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/11/the-unnamed/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Sep 2015 | Magazine, Volume 43.02 Summer 2014

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by Jason DaPonte, on privacy on the internet taken from the summer 2014 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend the Privacy in the digital age session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

“Government may portray itself as the protector of privacy, but it’s the worst enemy of privacy and that’s borne out by the NSA revelations,” web and privacy guru Jeff Jarvis tells Index.

Jarvis, author of Public Parts: How Sharing in the Digital Age Improves the Way We Work and Live argues that this complacency is dangerous and that a debate on “publicness” is needed. Jarvis defines privacy “as an ethic of knowing someone else’s information (and whether sharing it further could harm someone)” and publicness as “an ethic of sharing your own information (and whether doing so could help someone)”.

In his book Public Parts and on his blog, he advocates publicness as an idea, claiming it has a number of personal and societal benefits including improving relationships and collaboration, and building trust.

He says in the United States the government can’t open post without a court order, but a different principle has been applied to electronic communications. “If it’s good enough for the mail, then why isn’t it good enough for email?”

While Jarvis is calling for public discussion on the topic, he’s also concerned about the “techno panic” the issue has sparked. “The internet gives us the power to speak, find and act as a [single] public and I don’t want to see that power lost in this discussion. I don’t want to see us lose a generous society based on sharing. The revolutionaries [in recent global conflicts] have been able to find each other and act, and that’s the power of tech. I hate to see how deeply we pull into our shells,” he says.

The Pew Research Centre predicts that by 2025, the “internet will become like electricity – less visible, yet more deeply embedded in people’s lives for good and ill.” Devices such as Google Glass (which overlays information from the web on to the real world via a pair of lenses in front of your eyes) and internet-connected body monitoring systems like, Nike+ and Fitbit, are all examples of how we are starting to become surrounded by a new generation of constantly connected objects. Using an activity monitor like Nike+ means you are transmitting your location and the path of a jog from your shoes to the web (via a smartphone). While this may not seem like particularly private data, a sliding scale emerges for some when these devices start transmitting biometric data, or using facial recognition to match data with people you meet in the street.

As apps and actions like this become more mainstream, understanding how privacy can be maintained in this environment requires us to remember that the internet is decentralised; it is not like a corporate IT network where one department (or person) can switch the entire thing off through a topdown control system.

The internet is a series of interconnected networks, constantly exchanging and copying data between servers on the network and then on to the next. While data may take usual paths, if one path becomes unavailable or fails, the IP (Internet Protocol) system re-routes the data. This de-centralisation is key to the success and ubiquity of the internet – any device can get on to the network and communicate with any other, as long as it follows very basic communication rules.

This means there is no central command on the internet; there is no Big Brother unless we create one. This de-centralisation may also be the key to protecting privacy as the network becomes further enmeshed in our everyday lives. The other key is common sense. When asked what typical users should do to protect themselves on the internet, Jarvis had this advice: “Don’t be an idiot, and don’t forget that the internet is a lousy place to keep secrets. Always remember that what you put online could get passed around.”

As the internet has come under increasing control by corporations, certain services, particularly on the web, have started to store, and therefore control, huge amounts of data about us. Google, Facebook, Amazon and others are the most obvious because of the sheer volume of data they track about their millions of users, but nearly every commercial website tracks some sort of behavioural data about its users. We’ve allowed corporations to gather this data either because we don’t know it’s happening (as is often the case with cookies that track and save information about our browsing behaviour) or in exchange for better services – free email accounts (Gmail), personalised recommendations (Amazon) or the ability to connect with friends (Facebook).

“A transaction of mutual value isn’t surveillance,” Jarvis argues, referencing Google’s Priority Inbox (which analyses your emails to determine which are “important” based on who you email and the relevance of the subject) as an example. He expands on this explaining that as we look at what is legal in this space we need to be careful to distinguish between how data is gathered and how it is used. “We have to be very, very careful about restricting the gathering of knowledge, careful of regulating what you’re allowed to know. I don’t want to be in a regime where we regulate knowledge.”

Sinister or not, the internet giants and those that aspire to similar commercial success find themselves under continued and increasing pressure from shareholders, marketers and clients to deliver more and more data about you, their customers. This is the big data that is currently being hailed as something of a Holy Grail of business intelligence. Whether we think of it as surveillance or not, we know – at least on some level – that these services have a lot of our information at their disposal (eg the contents of all of our emails, Facebook posts, etc) and we have opted in by accepting terms of service when we sign up to use the service.

“The NSA’s greatest win would be to convince people that privacy doesn’t exist,” says Danny O’Brien, international director of the US-based digital rights campaigners Electronic Frontier Foundation. “Privacy nihilism is the state of believing that: ‘If I’m doing nothing wrong, I have nothing to hide, so it doesn’t matter who’s watching me’.”

This has had an unintended effect of creating what O’Brien describes as “unintentional honeypots” of data that tempt those who want to snoop, be it malicious hackers, other corporations or states. In the past, corporations protected this data from hackers who might try to get credit card numbers (or similar) to carry out theft. However, these “honeypot” operators have realised that while they were always subject to the laws and courts of various countries, they are now also protecting their data from state security agencies. This largely came to light following the alleged hacking of Google’s Gmail by China. Edward Snowden’s revelations about the United States’ NSA and the UK’s GCHQ further proved the extent to which states were carrying out not just targeted snooping, but also mass surveillance on their own and foreign citizens.

To address this issue, many of the corporations have turned on data encryption; technology that protects the data as it is in transit across the nodes (or “hops”) across the internet so that it can only be read by the intended recipient (you can tell if this is on when you see the address bar in your internet browser say “https” instead of “http”). While this costs them more, it also costs security agencies more money and time to try to get past it. So by having it in place, the corporations are creating a form of “passive activism”.

Jarvis thinks this is one of the tools for protecting users’ privacy, and says the task of integrating encryption effectively largely lies with the corporations that are gathering and storing personal information.

“Google thought that once they got [users’ data] into their world it was safe. That’s why the NSA revelations are shocking. It’s getting better now that companies are encrypting as they go,” he said. “It’s become the job of the corporations to protect their customers.”

Encryption can’t solve every problem though. Codes are made to be cracked and encrypted content is only one level of data that governments and others can snoop on.

O’Brien says the way to address this is through tools and systems that take advantage of the decentralised nature of the internet, so we remain in control of our data and don’t rely on third party to store or transfer it for us. The volunteer open-source community has started to create these tools.

Protecting yourself online starts with a common-sense approach. “The internet is a lousy place to keep a secret,” Jarvis says. “Once someone knows your information (online or not), the responsibility of what to do with it lies on them,” says Jarvis. He suggests consumers be more savvy about what they’re signing up to share when they accept terms and conditions, which should be presented in simple language. He also advocates setting privacy on specific messages at the point of sharing (for example, the way you can define exactly who you share with in very specific ways on Google+), rather than blanket terms for privacy.

Understanding how you can protect yourself first requires you to understand what you are trying to protect. There are largely three types of data that can be snooped on: the content of a message or document itself (eg a discussion with a counsellor about specific thoughts of suicide), the metadata about the specific communication (eg simply seeing someone visited a suicide prevention website) and, finally, metadata about the communication itself that has nothing to do with the content (eg the location or device you visited from, what you were looking at before and after, who else you’ve recently contacted).

You can’t simply turn privacy on and off – even Incognito mode on Google’s Chrome browser tells you that you aren’t really fully “private” when you use it. While technologies that use encryption and decentralisation can help protect the first two types of content that can be snooped on (specific content and metadata about the communication), there is little that can be done about the third type of content (the location and behavioural information). This is because networks need to know where you are to connect you with other users and content (even if it’s encrypted). This is particularly true for mobile networks; they simply can’t deliver a call, SMS or email without knowing where your device is.

A number of tools are on the horizon that should help citizens and consumers protect themselves, but many of them don’t feel ready for mainstream use yet and, as Jarvis argues, integrating this technology could be primarily the responsibility of internet corporations.

In protecting yourself, it is important to remember that surveillance existed long before the internet and forms an important part of most nation’s security plans. Governments are, after all, tasked with protecting their citizens and have long carried out spying under certain legal frameworks that protect innocent and average citizens.

O’Brien likens the way electronic surveillance could be controlled to the way we control the military. “We have a military and it fights for us…, which is what surveillance agencies should do. The really important thing we need to do with these organisations is to rein them back so they act like a modern civilised part of our national defence rather than generals gone crazy who could undermine their own society as much as enemies of the state.”

The good news is that the public – and the internet itself – appear to be at a junction. We can choose between a future where we can take advantage of our abilities to self-correct, decentralise power and empower individuals, or one where states and corporations can shackle us with technology. The first option will take hard work; the second would be the result of complacency.

Awareness of how to protect the information put online is important, but in most cases average citizens should not feel that they need to “lock down” with every technical tool available to protect themselves. First and foremost, users that want protection should consider whether the information they’re protecting should be online in the first place and, if they decide to put it online, should ensure they understand how the platform they’re sharing it with protects them.

For those who do want to use technical tools, the EFF recommends using ones that don’t rely on a single commercial third party, favouring those that take advantage of open, de-centralised systems (since the third parties can end up under surveillance themselves). Some of these are listed (see box), most are still in the “created by geeks for use by geeks” status and could be more user-friendly.

Privacy protectors

TOR

This tool uses layers of encryption and routing through a volunteer network to get around censorship and surveillance. Its high status among privacy advocates was enhanced when it was revealed that an NSA presentation had stated that “TOR stinks”. TOR can be difficult to install and there are allegations that simply being a TOR user can arouse government suspicion as it is known to be used by criminals. http://www.torproject.org

OTR

“Off the Record” instant messaging is enabled by this plugin that applies end-to-end encryption to other messaging software. It creates a seamless experience once set up, but requires both users of the conversation to be running the plug-in in order to provide protection. Unfortunately, it doesn’t yet work with the major chat clients, unless they are aggregated into yet another third party piece of software, such as Pidgin or Adium. https://otr.cypherpunks.ca/

Disconnect

This browser plugin tries to put privacy control into your hands by making it clear when internet tracking companies or third parties are trying to watch your behaviour. Its user-friendly inter- face makes it easier to control and understand. Right now, it only works on Chrome and Firefox. http://www.disconnect.me

Silent Circle

This is a solution for encrypting mobile communications – but only works between devices in the “silent circle” – so good for certain types of uses but not yet a mainstream solution, as encryption wouldn’t extend to all calls and messages that users make. Out-of-circle calls are currently only available in North America. https://silentcircle.com

©Jason DaPonte and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the summer 2014 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine, with a special report on propaganda and war. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

18 Mar 2015 | Magazine, mobile, News and features, Volume 44.01 Spring 2015

Women’s Voices by Meltem Arikan

Index on Censorship magazine’s editor, Rachael Jolley, introduces a special issue on refugee camps, looking at how migrants’ stories get told across the world, from Syria and Eritrea to Italy and the UK

Nothing is national any more, everything and everyone is connected internationally: economies, communication systems, immigration patterns, wars and conflicts all map across networks of different kinds.

Those linking networks can leave the world better informed and more aware of its connections, or those networks can fail to acknowledge their intersections, while carrying as much misinformation as information.

Where people are living in fear a connected world can be frightening, it can carry gossip and information back to those who pursue them. Decades ago, when people escaped from their homes to make a new life across the world, they were not afraid that their words, criticising the government they had fled from, could instantly be broadcast in the land they had left behind.

It is no wonder that in this more connected world, those fleeing persecution are more afraid to tell the truth about what the regime that tortured or imprisoned them has been doing. While, on the one hand, it should be easier to find out about such horrors, the way that your words can fly around the world in seconds adds enormous pressures not to speak about, or criticise, the country you fled from.

That fear often produces silence, leaving the wider world confused about the situation in a conflict-riven country where people are being killed, threatened or imprisoned. The consequences of instant communication can be terrifyingly swift.

Yet a different side of those networks, new apps or free phone services such as Skype, can provide some help in getting messages back to families left behind, giving them some hope about their loved ones’ future. That is one aspect that those in decades and centuries past, who fled their homelands, could never do. In the late 19th century, someone who escaped torture in Russia and travelled thousands of miles to the United States, might never speak to the family they had left behind again.

Communication has been revolutionised in the last two decades – where once a creaky telephone line was the only way of speaking to a sister or father across a continent or two, now Skype, Viber, Googlechat, and others offer options to see and speak every day.

In this issue’s special report Across the Wires, our writers and artists examine the threats of free expression within refugee camps, and as refugees desperately flee from persecution. Sources estimate that there are between 15.5 and 16.7 million refugees in the world today. Some are forced to live in camps for decades, others are fleeing from new conflicts, such as three million who have already left Syria. Many of us may know someone who has been forced to flee from another regime, those that don’t may in the future, and have some understanding of what that journey is like.

In this issue, writer Jason DaPonte examines how those who have escaped remain worried that their words will be captured and used against their families, and the steps they take to try avoid this. He also looks at “new” technology’s ability to keep refugees in touch with the outside world and to help tell the story of the camps themselves.

Italian journalist Fabrizio Gatti spent four years undercover, discovering details of refugee escape routes and people trafficking. In an extract from his book, previously unpublished in English, he tells his story of assuming the identity of a Kurdish man Bilal escaping torture, and fleeing to Italy via the Lampedusa detention camp, and the treatment he encountered. He speaks only Arabic and English to camp officials, but is able to hear what they said to each other in Italian about those seeking asylum. He uncovers the inhumanity and lack of rights those around him experienced in this powerful piece of writing.

Some of our authors in this issue speak from personal experience of seeking refuge, not speaking the language of the land they are forced to move to, and the steps they go through to resettle and be accepted in another land. Kao Kalia Yang’s family fled Laos during the Vietnam war, moving first to Thailand and then to the United States. She remembers how the family struggled first without understanding or speaking in Thai, then the same battles with English once they settled in the United States.

Ismail Einashe, whose family fled from Somaliland, talks to those who have escaped from one of the most secretive countries in the world, Eritrea. Einashe talks to Eritreans, now living in the UK, who are still afraid to speak openly about the conditions at home for fear of retribution.

The report also examines how the global media portrays refugee stories, the accuracy of those portrayals and how projects such as a new Syrian soap opera, partly written by a refugee, are giving asylum seekers and camp dwellers more power to tell the stories themselves.

But when people are escaping danger, the natural inclination is to stay quiet and under the radar. Some bravely do not. They intend to alert the world to a situation that is unfolding, and to attempt to protect others. Our report shows how much easier it is for the world’s citizens to find out about terrible persecution than it was in other eras, but how those communication tools can be turned back on those that are persecuted themselves. The push and pull of global networks, to be used for freedom or to silence others, is an on-going battle and one that we can only become more aware of.

Order your digital version of the magazine from anywhere in the world here

© Rachael Jolley