16 Dec 2013 | News

North Korea has expanded its deletion of a few hundred online articles mentioning Jang Song Thaek, the executed uncle of Kim Jong Un, to all articles on state media up to October 2013, numbering in the tens of thousands.

North Korea has expanded its deletion of a few hundred online articles mentioning Jang Song Thaek, the executed uncle of Kim Jong Un, to all articles on state media up to October 2013, numbering in the tens of thousands.

“It’s definitely the largest ‘management’ of its online archive North Korea has engaged in since it went online. No question,” Frank Feinstein, North Korea news analyst, told this writer on Sunday (15 December).

The Korean Central News Agency (www.kcna.kp), the state’s main organ, started publishing in its current online form on 1 January, 2012, and had some 39,000 Korean-language articles by mid-December 2013, with many translated into other languages. “Now however there are now no articles in the archive from prior to October 2013, with everything numbered to around 35,000 – or to October this year – gone,” said Feinstein, director of KCNA Watch, which analyses North Korean media for keywords and converts that into visual data to gauge reporting trends. Similar proportions of deletions were true for Korean Workers’ Party paper Rodong Sinmun and www.uriminzokkiri.com.

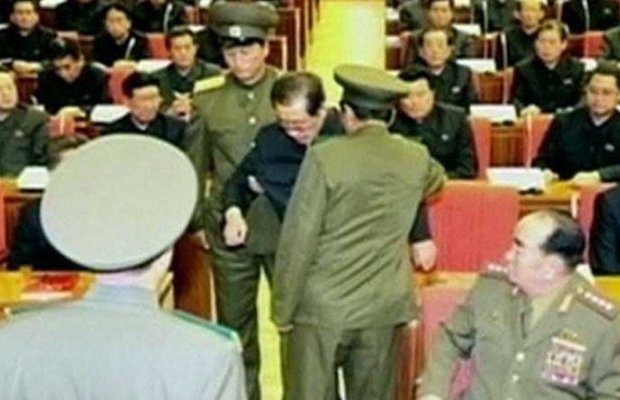

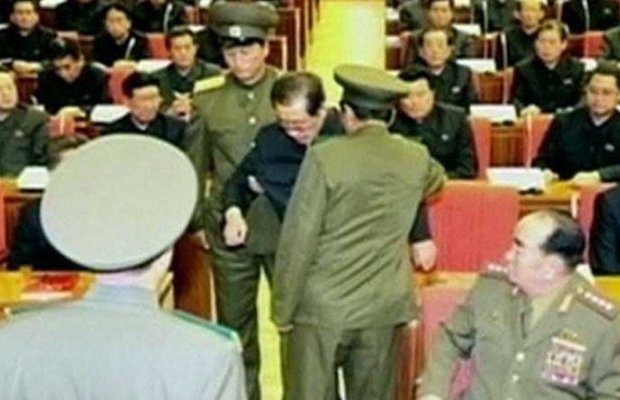

Just four days passed from the arrest Kim Jong Un’s uncle Jang, which was televised across North Korea, to his execution on 12 December 12. Thereafter the expurgation of any mention of Jang from the state news files took just hours. Following outages that to seemed affect several state online news sources, of some 550 Jang-related Korean articles on www.kcna.kp, Feinstein estimated that by late Friday, “every single one has either been altered, or deleted, without exception”. This included the most anodyne reports such as a 5 October KCNA story about Kim Jong Un visiting a hospital under construction now reads: “He personally named it ‘Okryu Children’s Hospital’ as it is situated in the area of Munsu where the clean water of the River Taedong flows.” But the original had continued: “He was accompanied by Jang Song Thaek, member of the Political Bureau of the CC, the WPK and vice-chairman of the NDC, and Pak Chun Hong, Ma Won Chun and Ho Hwan Chol, vice department directors of the CC, the WPK.”

Other examples are at the KCNA Watch site, and as also observed by North Korea watcher, Martyn Williams at www.northkoreatech.org.

What’s new about the North’s retrospective media management is its scale and that it’s doing it online, before a global audience. “This is North Korea censoring itself to the world – not just to its own citizens…Personally, I can’t believe they could think they’d get away with this sort of revisionism,” said Feinstein.

Nonetheless, the North can sustain its digital Ministry of Truth antics on the World Wide Web by preventing its output from being indexed. ‘It already works on KCNA – Google can’t index it at all. You can’t even link to an article on KCNA,’ said Feinstein, pointing to Google’s entire, paltry record of KCNA’s office in Pyongyang via this link.

It’s not clear even if South Korean intelligence or news agency Yonhap can archive KCNA’s database in its live form. “While North Korea doesn’t understand much about how to successfully operate online, they do understand this much.”

One theory contends that the North publishes different propaganda for internal and external consumption. For sure, North Korean people can only access news produced by the North Korean state, accessing www.kcna.kp through the country’s intranet, but more likely from the state TV, radio or newspapers on station platform hoardings of which obviously none enable access to digital or visual archives. TV has also been noted as adjusted, with a documentary first shown on 7 October 2013 being reshown on 7 December with Jang cut out of shots by adjusted focus and framing.

The upshot is this: “Our party, state, army and people do not know anyone except Kim Il Sung, Kim Jong Il and Kim Jong Un,” according to the sole English-language article left on KCNA that mentions Jang, a vicious 2,750-word denouncement from 13 December 13. The piece calls Jang “impudent, arrogant, reckless, rude and crafty,” “despicable human scum … worse than a dog,” who, backed by “ex convicts”, had plotted to destroy the economy before “rescuing” the country by military coup and billions earned from hoarded precious metals.

“They are serious about removing him from history,’ said Feinstein, except for passages such as “the era and history will eternally record and never forget the shuddering crimes committed by Jang Song Thaek, the enemy of the party, revolution and people and heinous traitor to the nation,” which concludes the KCNA piece. Meanwhile, “Rodong Simnun no longer knows Jang as anything other than a traitor,” tweeted Korea historian and linguist, Remco Breuker.

Traffic to www.kcna.kp has never been higher, even than for the death of Kim Jong Il, as people now follow stories to the source and are captivated by the apparent novelty of North Korea having an online presence, and one that uses such bizarre language. “Once they find KCNA, there’s no going back.” KCNA’s legitimacy as an analytical source for the North Korean state’s views is oft obscured by its saltier reportage.

Outside news sources are also sensationalist. While most Pyongyang watchers agree Jang was shot dead, Taiwanese news reported he’d been eaten by 120 dogs in front of Kim Jong Un and 300 government ministers in an hour-long death. Feinstein also pointed to a globally syndicated article before Jang’s trial that precipitously claimed www.kcna.kp had cleared out all Jang articles, when in fact articles mentioning Jang were still up. Basically, KCNA “has a bad search function”, said Feinstein.

While the case provides a tantalising view of what the Soviets might have done in the Internet age, it has also pushed out of the headlines another North Korea story, the release of American tourist Merrill Newman who had been held in North Korea since October on charges of “espionage” relating to his military service in Korea during the 1950-1953 war. Newman, who had gone to North Korea as a tourist, said he had not understood quite how far the North Korean state does not consider the war to be over – something arguably partly attributable to the US media barely ever mentioning the conflict, despite the country still being not at peace with North Korea.

Ironically, KCNA Watch has been blocked in South Korea since 25 October. Visitors to the site hit a Korea Communications Standards Commission (KSCS) blocking screen that says “connection to this website you tried to access is blocked as it provides illegal/hazardous information,” under the 1948 National Security Act, which restricts anti-state acts or material that endanger national security, including all printed and online matter from Pyongyang. Civilians seeking to analyse KCNA material in South Korea need official clearance, with the data viewed under armed guard and deleted immediately afterwards, said Feinstein. The block extends to foreign embassies in Seoul and is under increasing criticism as a blanket weapon for stifling dissent. In August the UN special rapporteur on human rights Margaret Sekaggya called it “seriously problematic for the exercise of freedom of expression”.

Sybil Jones

6 Nov 2013 | Africa, Digital Freedom, News, Uganda

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

The number of Ugandans with internet connectivity keeps on increasing, especially because of the influx of cheap handsets with internet access from China. Today, over 990,000 Ugandans have Facebook accounts. This though, is still a drop in the ocean keeping in mind that the country has a population over 35 million. By comparison, almost 20 million have access to mobile phones with SMS capabilities. The current Ugandan regime seeks to have direct control over all these vital information dissemination tools.

The Uganda Communications Commission (UCC), a government arm set up as a regulator of the telecommunications industry, is the government’s barking dog in this endeavour, and has often been let loose to abuse digital freedoms in the country. Among other things, a directive was issued to all telecom companies to register phone and data SIM cards they sell, capturing all details about the buyer. The government also uses the option to transfer money via mobile phones, offered by many telecom companies, to monitor activities of opposition politicians and activists. With the enactment of the Public Order Management Act (POMA) into law recently, the Ugandan police has set up several bureaus in its different departments to monitor the social media, calls and SMS of individuals from the opposition and civil society, as well as journalists and other activists. POMA is a draconian law that has been enacted to limit the movements and gatherings of people without police permission, among other harsh provisions.

Since the government of Uganda liberalised the economy in the 1990’s, several telecommunication companies and other Internet Service Providers (ISPs) have been offering telecom services in tandem with the international developments in that industry. Today, the biggest ISPs are the South African MTN, the French Orange, Bharti Airtel, which has now merged with Warid Telecom, and the indigenous UTL. During the riots of 2009 and 2011, UCC asked all ISPs to block emails, SMS and Facebook messages that had any political content or that mentioned names of certain government and opposition politicians. Although some protested, they had to give in or risk losing their operation licenses in the country. It should be noted too that all the telecommunication companies in the country have political godfathers high up in the echelons of the current government. With this arrangement, ISPs are easily beaten into the “correct line.”

Among the different social media channels available today like Whatsapp, Twitter and e-mails, Facebook remains one of the most widely used and fastest growing social media channel. All others are used basically by what one could term as Uganda’s elite class. The Ugandan police, on behalf of the government, recently asked Facebook to provide them with information held about all Ugandans with registered accounts – a request Facebook turned down. Many Ugandans are today able to air out their grievances with government through Facebook, and this is one of the highly monitored social media outlets by the government. Critics have used this outlet to discuss issues with the public, and the regime is not happy with it. The government manoeuvres clearly indicate that it would very much love to have total control of the social media channels, but it is hampered by the fact that all firms controlling these channels are abroad and out of its reach and patronage.

Take the case of the now famous Tom Voltaire Okwalinga (TVO), a Ugandan blogger who is also very active on Facebook. He has written extensively about the abuses of government, and he is one individual the Ugandan government would pay any price to identify and apprehend. Despite the government’s efforts to identify him and the number of security operatives that have been deployed to apprehend this individual, TVO has developed a big following on Facebook, usually commenting on his exposés.

His case shows how, in the nutshell, the Ugandan government is trying to gain an upper hand in controlling and curbing digital freedoms in the country.

This article was originally posted on 6 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

4 Nov 2013 | Digital Freedom, News

We can partially blame gerrymandering for the current gridlock in the U.S. Congress. By shaping the electoral map to create politically safe spaces, we have generated a fractious body that often clashes rather than collaborates, limiting our chances of resolving the country’s toughest challenges. Unfortunately, revelations about the global reach of American security surveillance programs under the National Security Agency (NSA) are leading some to propose what amounts to gerrymandering for the internet in order to route around NSA spying. This will shackle the internet, inherently change its technical infrastructure, throttle innovation, and likely lead to far more dangerous privacy violations around the globe.

Nations are rightly upset that the communications of their citizens are swept up in the National Security Agency’s pervasive surveillance dragnet. There is no question the United States has overreached and violated human rights in its collection of communications information on innocent people around the globe; however, the solution to this problem should not, and truly cannot, be data localization mandates that restrict data storage and flow.

The calls for greater localization of data are not new, but the recent efforts of Brazil’s President, Dilma Rouseff, to protect Brazilians from NSA spying reflected the view of many countries suddenly faced with a new threat to the privacy of the communications of their citizens. Rouseff has been an advocate for internet freedom, so undoubtedly her proposal is well intentioned, though the potential unintended repercussions are alarming.

First, it’s important to consider the technical reasons why data location requirements are a really bad idea. The Internet developed in a widely organic manner, creating a network that allowed data to flow from all corners of the world – regardless of political boundaries, residing everywhere and nowhere at the same time. This has helped increase the resilience of the internet and it has promoted significant efficiencies in data flow. As is, the network routes around damage, and data can be wherever it best makes sense and take an optimal route for delivery.

Data localization mandates would turn the internet on its head. Instead of a unified internet, we would have a fractured internet that may or may not work seamlessly. We would instead see districts of communications that cater to specific needs and interests – essentially we would see Internet gerrymandering at its finest. Countries and regions would develop localized regulations and rules for the internet to benefit them in theory, and would certainly aim to disadvantage competitors. The potential for serious winners and losers is huge. Certainly the hope for an internet that promotes global equality would be lost.

Data localization may only be a first step. Countries seeking to keep data out of the United States or that want to exert more control over the internet may also mandate restrictions on how data flows and how it is routed. This is not far-fetched. Countries such as Russia, the United Arab Emirates, and China have already proposed this at last year’s World Conference on International Telecommunications.

As internet traffic begins to demand more bandwidth, especially as we witness more real-time multimedia applications, efficient routing is essential to advance new internet services. High capacity applications like Apple’s FaceTime may slow to the painful crawl reminiscent of the dial-up days of the internet.

This only begins to illustrate the challenges internet innovators would face, but big established players like Facebook, Google and Microsoft, would potentially have the resources to abide by localization mandates – of course, only if the business case supports working in particular locales. Some countries with local storage rules may be bypassed altogether. For small or emerging businesses, data localization requirements would be a greater challenge. It would build barriers to markets and shut off channels for innovation. Few emerging businesses could afford to locate servers in every new market, and if local data server requirements become ubiquitous, it will be businesses in emerging markets that are most disadvantaged. The reality for developing nations is that protectionist measures such as data localization will further isolate local business from the global market, depriving them of the advantages for growth that are provided by the borderless internet.

Most important though, is the potential for fundamental harm to human rights due to data localization mandates. We recognize that this is a difficult argument to accept in the wake of the revelations about NSA surveillance, but data localization requirements are a double-edged sword. It is important to remember that human rights and civil liberties groups have long been opposed to data localization requirements because if used inappropriately, such requirements can become powerful tools of control, intimidation and oppression.

When companies were under intense criticism for turning over the data of Chinese activists to China, internet freedom activists were united in theirs calls to keep user data out of the country. When Yahoo! entered the Vietnamese market, it placed its servers out of the country in order to better protect the rights of its Vietnamese users. And the dust up between the governments of the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, India, and Indonesia, among others, demanding local servers for storage of BlackBerry messages in order to ensure legal accountability and meet national security concerns, was met with widespread condemnation. Now with democratic governments such as Brazil and some in Europe touting data localization as a response to American surveillance revelations, these oppressive regimes have new, albeit inadvertent, allies. While some countries will in fact store, use and protect data responsibly, the validation of data localization will unquestionably lead to many regimes abusing it to silence critics and spy on citizens. Beyond this, data server localization requirements are unlikely to prevent the NSA from accessing the data. U.S. companies and those with a U.S. presence will be compelled to meet NSA orders, and there appear to be NSA access points around the world.

Data localization is a proposed solution that is distracting from the important work needed to improve the Internet’s core infrastructural elements to make it more secure, resilient and accessible to all. This work includes expanding the number of routes, such as more undersea cables and fiber runs, and exchange points, so that much more of the world has convenient and fast Internet access. If less data is routed through the U.S., let it be for the right reason: that it makes the Internet stronger and more accessible for people worldwide. We also need to work to develop better Internet standards that provide usable privacy and security by default, and encourage broad adoption.

Protecting privacy rights in an era of transborder surveillance won’t be solved by ring fencing the Internet. It requires countries, including the U.S., to commit to the exceedingly tough work of coming to the negotiating table to work out agreements that set standards on surveillance practices and provide protections for the rights of privacy and free expression for people. Germany and France have just called for just such an agreement with the U.S. This is the right way forward.

In the U.S., we must reform our surveillance laws, adopt a warrant requirement for stored email and other digital data, and implement a consumer privacy law. The standards for government access to online data in all countries must likewise be raised. These measures are of course much more difficult in the short run that than data localization requirements, but they are forward-looking, long-term solutions that can advance a free and open internet that benefits us all.

Joseph Lorenzo Hall, Chief Technologist at Center for Democracy and Technology, co-authored this piece with Leslie Harris.

This article was originally posted on 4 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Oct 2013 | Digital Freedom

Last year’s Internet Governance Forum in Baku, Azerbaijan proved controversial due to the choice of host. This year’s event, in Bali, Indonesia was bound to be contentious, after Edward Snowden’s leaks on the US’s PRISM programme. PRISM and TEMPORA (the UK system of mass surveillance) were a lightening rod for general discontent from activists who feel an increasing sense of ill ease over the state of internet freedom. Many of the sessions were bad-tempered affairs with civil society rounding on the perceived complacency of government officials from democracies who refused to state their opposition to mass state surveillance in clear enough terms.

At an event hosted by the Global Network Initiative, Index on Censorship, andPakistan’s Centre for Social and Policy Analysis, a US government official was heckled by the audience when he attempted to justify PRISM as an anti-terrorism measure. Of particular concern for delegates was a sense that PRISM is now being used by less democratic and authoritarian states to justify their own surveillance systems. The Chinese were quick to point out the ‘double standards’ of the US at this workshop, following it with appalling doublespeak to gloss over their poor domestic record on human rights violations. A point I challenged them on in no uncertain terms.

Participants in the workshop from across the globe from Pakistan to South Africa stated their concern that a race to the bottom is beginning with new surveillance capacities being debated in countries such as Russia, New Zealand and the UK. Other areas of concern at the workshop included the increasing use of filters at ISP level (in particular in Indonesia where a significant number of ISPs are adopting filtering) and the pressure now felt by Telcos from states who are imposing burdensome requirements to filter content. One worrying prospect is that the ITU will succumb to a push to ensure Telcos do not distribute ‘blasphemous’ content which could lead to the full Balkanisation of the internet.

Although the outlook is bleak, civil society is pushing back at corporations and governments. Bytes for All in Pakistan has done impressive work in chronicling censored online content. A number of coalitions strengthened at the IGF with closer co-operation between international NGOs to take on mass state surveillance. This weekend, a number of US NGOs will rally in Washington DC against the PRISM programme with thousands expected to take to the streets. Index on Censorship’s #DontSpyOnMe petition of 7,000 signatures was this week sent to Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaitė, who currently hold the Presidency of the Council of the EU, and Herman van Rompuy, President of the European Council. The EU heeded our calls to discuss mass surveillance at the Council of Ministers meeting – a big success. The pressure on corporations is being felt too, Telcos came under particular fire for their willingness to install surveillance equipment in their networks. Yet, many are beginning to speak publicly over the pressures they feel from states and the need for transparency so their users are at least aware of the surveillance they may be subject to and so can adjust their behaviour accordingly. Meanwhile, Google launched new tools to illustrate the threats the internet faces. The Digital Attack Map is a realtime website displays DDOS attacks and where they originate from – useful in tracking attacks on civil society websites from state-run or criminal botnets. Google also launched a project to provide free, secure web hosting for internet activists under attack.

One of the strengths of the IGF is the broadness of the workshop programme. From the challenges felt by the disabled online, minority rights online, through to bridging the ‘digital divide’ between the rich and poor both internationally and internally within even wealthier countries, the IGF covered a significant amount of ground. Yet, one of the big challenges to the IGF is how to engage a wider section of civil society. While the IGF was better attended by delegates from South-East Asia, fewer delegates from Europe and the Middle East were visible during this IGF. This remains a challenge to the organisers, with too much interaction from those physically present at the conference and too little from the many remote participants, many of whom couldn’t afford the air fare to Bali but have much to contribute. Bridging this divide will be important in the future.

The tone of this IGF was set by the Snowden revelations. The US and other Western democracies were on the back foot, in stark contrast to their confident promotion of net freedom in Baku. Without openess, increased transparency and an end to mass surveillance it’s hard to see how they will regain their moral authority, leaving a huge vacuum at the heart of these debates. A vacuum that others – in particular China – are willing to fill. The battle to keep the multistakeholder, open internet free from top-down state interference is on-going. The IGF should give once confident advocates of net freedom serious pause for thought.

North Korea has expanded its deletion of a few hundred online articles mentioning Jang Song Thaek, the executed uncle of Kim Jong Un, to all articles on state media up to October 2013, numbering in the tens of thousands.

North Korea has expanded its deletion of a few hundred online articles mentioning Jang Song Thaek, the executed uncle of Kim Jong Un, to all articles on state media up to October 2013, numbering in the tens of thousands.