25 Oct 2013 | Asia and Pacific, Digital Freedom, India, News and features

Just days before the United Nation’s led Internet Governance Forum in Indonesia, India, held its own – and first of its kind – conference on cyber governance and cyber security.

With the support of the National Security Council Secretariat of the Government of India, the two-day conference was organized by private think-tank Observer Research Foundation and industry body, Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry, (FICCI). Speakers were from a host of countries including Estonia, Germany, Belgium, Australia, Russia, Israel, and of course, India.

It was ironic, that in a post-Snowden world, buried under allegations of the extent of the NSA’s spying, US officials were unable to attend the conference due to their government’s shutdown. Instead, other views took center stage, and India also visibly demonstrated the various positions its stakeholders take around the questions of governance and security.

Right at the kickoff, India’s Minister for Communications and Technology, Kapil Sibal, challenged the question of sovereignty and jurisdiction in cyberspace. “If there is a cyber space violation and the subject matter is India because it impacts India, then India should have jurisdiction. For example, if I have an embassy in New York, then anything that happens in that embassy is Indian territory and there applies Indian Law.”

India has, over the last few years, flirted with the idea of an UN-lead internet governance structure, and subsequently backed away from it. Minister Sibal said that India believes in “complete freedom of the internet”, however, at the same time needs to acknowledge that along with cyber freedoms come cyber gangsters, and the state and its citizens need to be protected from them.

India, with its 860 million mobile subscriptions (although, the numbers of users would be lower than this figure) is looking more and more to the internet as a delivery platform of socio-economic programs and a tool to boost the economy. That the internet can raise GDP by 10% is a much favored figure for those who promote the internet for economic reasons. The fact is that as the remaining unconnected population of India begins to acquire net connections through desktops and smart phones, the government is increasingly looking at security and surveillance over the internet as a necessary and inevitable route. This also means that the government needs to rely on industry to help them with this gigantic task.

The possible synergy between businesses and government in India was a central theme for discussion; as industry bodies asked the government to invest in training more cyber security specialists and also start moving towards uniform security standards and protocols. In fact, Indian industry most certainly wants to be relived of the financial burden of training personnel, and to an extent, investment in security R&D, and is keen to partner with the government to achieve both ends. Indian industry is often in the news because it appears almost universally under prepared for cyber attacks, both from within the country and externally. Suggestions of a government-led cyber awareness program were made as well, with calls to allocate funds for these exercises in the budget.

However, as has been the case in India, the real source of friction still lies between civil society and the government over the question of surveillance and monitoring. In a session entitled ‘Privacy and National Security’; perhaps the only India-centric panel of the entire conference, the debate became overheated. The panel consisted of a senior police officer involved in surveillance, India’s director-general of CERT (Computer Emergency Response Team), a representative from the mobile industry and a privacy expert. The government official was pushed by civil society members and journalists to explain the workings of the Central Monitoring System, still very opaque to the public, and later the official definition of privacy. He did neither. Unsurprisingly, India is yet to really define what privacy is, leading to simultaneous furor in the room and twitter (#cyfy13) about why this hasn’t been done as yet.

The sense in the room was that surveillance, while necessary to protect citizens, is only really effective when it is conducted in a targeted manner. Mass surveillance leads to self-censorship and is, in the end, counter productive. The other bone of contention was the question of identity, with the government making arguments that verifiable cyber identity is a possible solution to cyber crime. However, other participants found the issue troubling, as anonymity is necessary for a number of reasons, including as we have seen around the world, political dissent.

Finally, panelists discussed how best to inculcate a multistakeholder approach when legislating the internet. It was pointed out more than once that the internet was a product of private enterprise, made on open standards and principles, but now governments are attempting to control this resource. However, while public calls for multistakeholderism were made for many reasons; human rights, protection of privacy and even to benefit business in the long run (as they would not risk being caught up in lengthy court cases in the future if they took civil society on board from the start), there was still an elephant in the room. Offline, many official participants wondered why Chatham House Rules were not observed, or why there were no closed-door meetings only for government officials. It was clear that much of the weighty – and honest – discussions still don’t involve the public. Perhaps not where the question of governance is, but certainly when the question of security is.

Ultimately, there are two broad outcomes of this conference. The first is that India has indicated its willingness to start shouldering discussions to do with the global cyberspace. The other is, as India’s National Security Advisor put it, — ““India has a national cybersecurity policy not a national cybersecurity strategy.” This is certainly a start to building a consensus for that strategy.

This article was posted at indexoncensorship.org on 25 Oct 2013.

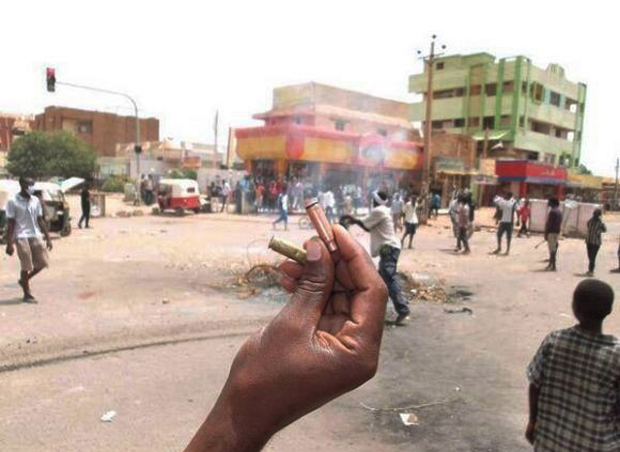

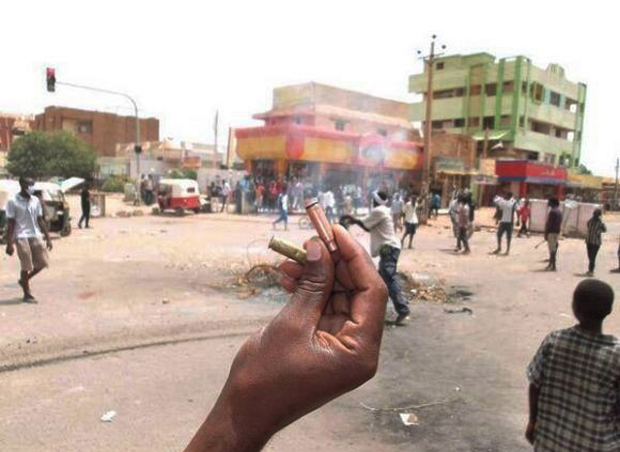

27 Sep 2013 | Digital Freedom, Middle East and North Africa, News and features, Sudan

Reports of at least 50 dead have been received from Sudan.

There’s no trying to hide what’s happening within the urban centres of Sudan today. On Wednesday, September 25 at about 1pm, the Sudanese authorities completely shut down the country’s global internet for 24 hours. This happened against the backdrop of spreading peaceful protests following the regime’s decision to lift state subsidies from basic food items and fuel.

In the last few weeks, Sudan’s citizens have been feeling the burden of increasing prices as the Sudanese pound depreciated sharply, and purchasing power declined in a country where 46 percent of the population live in poverty. The lifting of subsidies was met with a popular outburst, especially after a public TV speech by President Omer Al Bashir made it clear that his government has no concrete solutions. He went on to mock the population saying they did not know what hot dogs were before he came to power.

The protests, which started in Wad Madani in Gaziera state, have so far spread to Sudan’s major towns including Nyala in war-struck Darfur. They have been met with unprecedented government violence in the Northern cities of Sudan which have traditionally been peaceful. Live ammunition has been used against protesters, many of whom are school students and youth in their early to mid twenties. By the third day of protests the death toll in Khartoum alone exceeded 100, and 12 in Wad Madani. There have been arrests amongst political leaders, activists and protesters, with more than 80 detainees from Madani alone.

Sudan’s government has cracked down violently, using live ammunition to disperse demonstrators.

Protesters are mainly calling for the regime to step down, with chants of, “liberty, justice, freedom”, “the people want the downfall of the regime”, and “we have come out for the people who stole our sweat”. These protests lack any political or civil society leadership, and so far not a single statement has come from the umbrella of opposition parties, the National Coalition Forces.

Crackdown on the internet and print media

The internet blackout imposed by Sudan’s National Congress Party (NCP) was an intentional ploy aimed at limiting the outflow of information, especially the very graphic images of protesters lying dead in the streets, as well as the images from hospital morgues showing protesters with fatal injuries to the head and upper torso areas. It is clear that this show of force is meant to frighten Sudanese citizens and deter additional protests. (Graphic Images: Street | Street)

This is not the first time the regime in Khartoum has shut down the internet. In June 2013 there was an 8-hour internet blackout during a gathering organized by the Ansar (an off-shoot of the Umma Party) that attracted thousands of people. During the protests last year, dubbed Sudan Revolts, the internet slowed down drastically on the night of June 29, before a large protest was announced.

Since the independence of South Sudan in July 2011, Sudan has also experienced a general clampdown on the media. On September 19, before the start of the protests on Monday, newspapers writing about the economic situation including Alayaam, Al Jareeda and the pro-government Al Intibaha, were confiscated. On Thursday, newspapers including included Al Ayaam and Al Jareeda, refused to print because of the government imposed censorship that prohibits any mention of the ongoing protests. Today Al Sudani and Al Mahjar newspapers (both pro-government) were confiscated, and Al Watan was not allowed to go to press.

The government of Sudan cut the country off from the internet as protests against the end of fuel subsidies spread.

With most citizens and activists relying completely on social media outlets and internet access through mobile phones to share information, footage and photos, the internet remains the only affordable means to communicate with the outside world. Other options, such as dial-up using modems are not viable for Sudan, as most people have no landlines to connect via modems and depend on mobile devices to access the internet.

During the internet blackout many reported that even SMS messages were blocked. And services such as tweeting via SMS were interrupted by the sole telecommunications provider that carries this service-Zain.

Popular anger and continuing protests

Contrary to the government’s intention the excessive use of force against protesters, the rising death toll and continuing rumours that the internet may be shut down again have not dissuaded citizens, but rather made them more angry and determined, with protests lasting long after midnight in Khartoum. As the streets of the capital and other towns filled up with security agents, riot police and armed government militias, citizens have nonetheless buried their dead in large and angry processions.

Today has been called Martyr’s Friday, in remembrance of all those who have fallen. Protests have been announced in all of Sudan’s towns. In some areas of Khartoum, citizens reported that they were not allowed into mosques for Friday prayers, and that the mosques had a heavy presence of security agents in civilian clothes. This move shows that the regime is anxious protests may follow after the prayers, as well as fearing the possible politicisation of the Friday sermons which may incite more anger.

Nonetheless, this has not deterred more than 2,000 protesters to congregate in Rabta Square, Shambat Barhry (in Khartoum). While writing this, a protester called me to say his internet was not working, and described that even leaders from the communist party, Popular Congress Party and others were starting to arrive. I could hear him with difficulty, but chants in the background were clear, “ya Khartoum, thouri, thouri”—Khartoum, revolt, revolt.

So far one thing is clear: these protests are not a replay of last year’s summer protests that were mainly triggered by university students and youth movements. These are street-supported protests–something that previous protests lacked and a game changer for the NCP who is gradually losing its grip on power.

This article was originally posted on 27 Sept 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

This article was edited on 5 November 2013 at 13:50. The article originally stated that the internet blackout took place on Wednesday 26 September. It took place on 25 September.

22 Jul 2013 | United Kingdom

Full text of David Cameron’s speech today:

Today I am going to tread into territory that can be hard for our society to confront, that is frankly difficult for politicians to talk about — but that I believe we need to address as a matter of urgency.

I want to talk about the Internet: the impact it is having on the innocence of children, how online pornography is corroding childhood, and how, in the darkest corners of the Internet, there are things going on that are a direct danger to our children, and that must be stamped out.

I’m not making this speech because I want to moralise or scaremonger, but because I feel profoundly as a politician — and as a father — that the time for action has come. This is, quite simply, about how we protect our children and their innocence.

Let me be very clear, right at the start: the Internet has transformed our lives for the better. It helps liberate those who are oppressed, it allows people to tell truth to power, it brings to education to those previously denied it, it adds billions to our economy, it is one of the most profound and era-changing inventions in human history.

But because of this, the Internet can sometimes be given a special status in debate. In fact, it can be seen as beyond debate. To raise concerns about how people should access the Internet or what should be on it is somehow naïve or backward-looking. People feel they are being told the following:

“An unruly, un-ruled Internet is just a fact of modern life”

“Any fall out from that is just collateral damage”

“You can easily legislate what happens on the Internet as you can legislate the tides”

Against this mindset, people — and most often parents’ — very real concerns are dismissed. They’re told “the Internet is too big to mess with, too big to change.” But to me, the questions around the Internet and the impact it has are too big to ignore. The Internet is not just where we buy, sell and socialise. It is where crimes happen and where people can get hurt, and it is where children and young people learn about the world, each other, and themselves.

The fact is that the growth of the Internet as an unregulated space has thrown up two major challenges when it comes to protecting our children. The first challenge is criminal: and that is the proliferation and accessibility of child abuse images on the Internet. The second challenge is cultural: the fact that many children are viewing online pornography and other damaging material at a young age, and that the nature of that pornography is so extreme it is distorting their view of sex and relationships.

Let me be clear: these challenges are very distinct and very different.

In one we’re talking about illegal material. The other legal material is being viewed by those who are underage. But both these challenges have something in common. They are about how our collective lack of action on the Internet has led to harmful — and in some cases truly dreadful — consequences for children.

Of course, a free and open Internet is vital. But in no other market — and with no other industry — do we have such an extraordinarily light touch when it comes to protecting our children. Children can’t go into shops or the cinema and buy things meant for adults or have adult experiences — we rightly regulate to protect them. But when it comes to the Internet, in the balance between freedom and responsibility, we have neglected our responsibility to our children.

My argument is that the Internet is not a sideline to ‘real life’ or an escape from ‘real life’; it is real life.

It has an impact: on the children who view things that harm them, on the vile images of abuse that pollute minds and cause crime, on the very values that underpin our society. So we have got to be more active, more aware, more responsible about what happens online. And I mean ‘we’ collectively: governments, parents, Internet providers and platforms, educators and charities. We’ve got to work together across both the challenges I have set out.

Let me start with the criminal challenge: and that is the proliferation of child abuse images online. Obviously, we need to tackle this at every step of the way, whether it’s where this material is hosted, transmitted, viewed, or downloaded.

I am absolutely clear that the State has a vital role to play. The police and CEOP — that is the Child Exploitation and Online Protect Centre — are already doing a good job in clamping down on the uploading and hosting of this material in the UK. Indeed, they have together cut the total amount of known child abuse content hosted in the UK from 18 per cent of the global total in 1996 to less than one per cent today. They are also doing well on disrupting the so-called ‘hidden Internet’, where people can share illegal files, and on peer-to-peer sharing of images through photo-sharing sites or networks away from the mainstream Internet.

Once the CEOP becomes a part of the National Crime Agency, that will further increase their ability to investigate behind paywalls, to shine a light on the ‘hidden Internet’, and to drive prosecutions of those who are found to use it. So let me be clear to any offender who might think otherwise: there is no such thing as a ‘safe’ place on the Internet to access child abuse material.

But the government needs to do more.

We will give CEOP and the police all the powers they need to keep pace with the changing nature of the Internet. And today I can announce that from next year, we will also link up existing fragmented databases across all the police forces to produce a single secure database of illegal images of children, which will help police in different parts of the country work together more effectively to close the net on paedophiles.

It will also enable the industry to use the digital hash tags from the database to proactively scan for, block, and take down these images whenever they occur. And that’s exactly what the industry has agreed to do, because this isn’t just a job for government. The Internet Service Providers and the search engine companies have a vital role to play, and we have already reached a number of important agreements with them.

A new UK-US taskforce is being formed to lead a global alliance with the big players in the industry to stamp out these vile images. I have asked Joanna Shields, CEO of Tech City and our Business Ambassador for Digital Industries, who is here today, to head up engagement with industry for this task force, and she will work with both the UK and US governments and law enforcement agencies to maximise our international efforts.

Here in Britain, Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo are already actively engaged on a major campaign to deter people who are searching for child abuse images. I cannot go into detail about this campaign, because that would undermine its effectiveness, but I can tell you it is robust, it is hard-hitting, and it is a serious deterrent to people looking for these images. When images are reported they are immediately added to a list and blocked by search engines and ISPs, so that people cannot access those sites.

These search engines also act to block illegal images and the URLs, or pathways that lead to these images from search results, once they have been alerted to their existence. But here, to me, is the problem: the job of actually identifying these images falls to a small body called the Internet Watch Foundation. This is a world-leading organisation, but it relies almost entirely on members of the public reporting things they have seen online.

So, the search engines themselves have a purely reactive position. When they’re prompted to take something down, they act. Otherwise, they don’t. And if an illegal image hasn’t been reported, it can still be returned in searches. In other words, the search engines are not doing enough to take responsibility.

Indeed in this specific area they are effectively denying responsibility, and this situation has continued because of a technical argument. It goes that the search engines shouldn’t be involved in finding out where these images are, that they are just the ‘pipe’ that delivers the images, and that holding them responsible would be a bit like holding the Post Office responsible for sending on illegal objects in anonymous packages.

But that analogy isn’t quite right, because the search engine doesn’t just deliver the material that people see, it helps to identify it.

Companies like Google make their living out of trawling and categorising content on the web so that in a few key-strokes you can find what you’re looking for out of unimaginable amounts of information. Then they sell advertising space to companies, based on your search patterns. So to return to that analogy, it would be like the Post Office helping someone to identify and order the illegal material in the first place, and then sending it onto them, in which case they absolutely would be held responsible for their actions.

So quite simply: we need the search engines to step up to the plate on this.

We need a situation where you cannot have people searching for child abuse images and being aided in doing so. Where if people do try and search for these things, they are not only blocked, but there are clear and simple signs warning them that what they are trying to do is illegal, and where there is much more accountability on the part of the search engines to actually help find these sites and block them.

On all these things, let me tell you what we’ve already done and what we are going to do. What we have already done is insist that clear, simple warning pages are designed and placed wherever child abuse sites have been identified and taken down, so that if someone arrives at one of these sites they are clearly warned that the page contained illegal images. These splash pages are up on the Internet from today, and this is a vital step forward.

But we need to go further. These warning pages should also tell those who’ve landed on it that they face consequences, such as losing their job, their family, even access to their children if they continue. And vitally, they should direct them to the charity campaign ‘Stop It Now’, which can help them change their behaviour anonymously and in complete confidence.

On people searching for these images, there are some searches where people should be given clear routes out of that search to legitimate sites on the web. So here’s an example: If someone is typing in ‘child’ and ‘sex’ there should come up a list of options:

‘Do you mean child sex education?’

‘Do you mean child gender?’

What should not be returned is a list of pathways into illegal images which have yet to be identified by CEOP or reported to the IWF.

Then there are some searches which are so abhorrent, and where there can be no doubt whatsoever about the sick and malevolent intent of the searcher, where there should be no search results returned at all. Put simply — there needs to be a list of terms — a black list — which offer up no direct search returns.

So I have a very clear message for Google, Bing, Yahoo, and the rest: you have a duty to act on this, and it is a moral duty.

I simply don’t accept the argument that some of these companies have used to say that these searches should be allowed because of freedom of speech. On Friday I sat with the parents of Tia Sharp and April Jones. They want to feel that everyone involved is doing everything they can to play their full part in helping to rid the internet of child abuse images.

So I have called for a progress report in Downing Street in October, with the search engines coming in to update me. The question we have asked is clear: If CEOP give you a black-list of internet search terms, will you commit to stop offering up any returns to these searches?

If in October we don’t like the answer we’re given to this question, if the progress is slow or non-existent, then I can tell you we are already looking at the legislative options we have to force action. And there’s a further message I have for the search engines. If there are technical obstacles to acting on this, don’t just stand by and say nothing can be done; use your great brains to help overcome them.

You’re the people who have worked out how to map almost every inch of the earth from space, who have developed algorithms that make sense of vast quantities of information. You’re the people who take pride in doing what they say can’t be done. You hold hackathons for people to solve impossible Internet conundrums, well — hold a hackathon for child safety.

Set your greatest brains to work on this. You are not separate from our society, you are part of our society, and you must play a responsible role in it. This is quite simply about obliterating this disgusting material from the net — and we will do whatever it takes.

So that’s how we are going to deal with the criminal challenge. The cultural challenge is the fact that many children are watching online pornography — and finding other damaging material online — at an increasingly young age.

Now young people have always been curious about pornography and they have always sought it out. But it used to be that society that could protect children by enforcing age restrictions on the ground, whether that was setting a minimum age for buying top-shelf magazines, putting watersheds on the TV, or age rating films and DVDs. But the explosion of pornography on the Internet, and the explosion of the Internet into children’s lives — has changed all that profoundly. It’s made it much harder to enforce age restrictions, and much more difficult for parents to know what’s going on.

But we as a society need to be clear and honest about what is going on.

For a lot of children, watching hardcore pornography — is in danger of becoming a rite of passage. In schools up and down our country, from the suburbs to the inner city, there are young people who think it’s normal to send pornographic material as a prelude to dating, in the same way you might once have sent a note across the classroom. Over a third of children have received a sexually explicit text or email. In a survey, a quarter of children said they’d seen pornography which had upset them. This is happening. It’s happening on our watch as adults.

And the effect can be devastating. Our children are growing up too fast. They are getting distorted ideas about sex and being pressured in a way we have never seen before. As a father, I am extremely concerned about this.

Now this is where some could say: ‘it’s fine for you to have a view as a parent; but not as Prime Minister… this is an issue for parents, not for the state.’

But the way I see it, there is a contract between parents and the state. Parents say ‘we’ll do our best to raise our children right’, and the state agrees to stand on their side; to make that job a bit easier, not harder.

But when it comes to Internet pornography, parents have been left too much on their own, and I am determined to put that right. We all need to work together, both to prevent children from accessing pornography, and to educate them about keeping safe online.

This is about access and it’s about education, and let me tell you what we’re doing on each. On access, things have changed profoundly in recent years. Not long ago, access to the Internet was mainly restricted to the PC in the corner of the living room, with a beeping dial up modem, downstairs in the house where parents could keep an eye on things. Not it’s on smartphones, laptops, tablet computers, and game consoles. And with high speed connections that make movie downloads and real time streaming possible. Parents need even more help to protect their children across all these fronts.

So on mobile phones, it is great to report that all of the operators have now agreed to put adult content filters onto phones automatically. To deactivate them you will need to prove that you are over 18, and the operators will continue to refine and improve those filters. On public Wi-Fi — of which more than 90 per cent is provided by six companies — O2, Virgin Media, Sky, Nomad, BT, and Arqiva. I’m pleased to say that we have now reached an agreement with all of them that family-friendly filters are applied across the public Wi-Fi network, wherever children are likely to be present. This will be done by the end of next month. And we are keen to introduce a “Family Friendly Wi-Fi” symbol which retailers, hotels and transport companies can use to show their customers that their public Wi-Fi is filtered.

That is how we’re protecting children outside of the home. Inside the home, on the private family network, it is a more complicated issue. There has been a big debate about whether Internet filters should be set to a default ‘on’ position. In other words, with adult content filters applied by default — or not.

Let’s be clear: this has never been a debate about companies or governments censoring the Internet, but about filters to protect children at the home network level. Those who wanted default ‘on’ said it’s a no-brainer: just have the filters set to ‘on’, then adults can turn them off if they want to. And that way, we can protect all children, whether their parents are engaged in Internet safety or not.

But others said default ‘on’ filters could create a dangerous sense of complacency. They said that with default filters, parents wouldn’t bother to keep an eye on what their kids are watching, as they’d be complacent and assume the whole thing was taken care of.

I say we need both: we need good filters that are pre-selected to be on unless an adult turns them off, and we need parents aware and engaged in the setting of those filters. So that’s what we’ve worked hard to achieve. I appointed Claire Perry to take charge of this, for the very simple reason that she is passionate about this issue and determined to get things done. She has worked with the big four Internet service providers. TalkTalk, Virgin, Sky, and BT who together supply Internet connections to almost 9 out of 10 homes.

And today, after months of negotiation, we have agreed home network filters that are the best of both worlds. By the end of this year, when someone sets up a new broadband account, the settings to install family friendly filters will be automatically selected. If you just click “next” or “enter”, then the filters are automatically on. And, in a really big step forward, all the ISPs have rewired their technology so that once your filters are installed, they will cover any device connected to your home Internet account.

No more hassle of downloading filters for every device, just one click protection. One click to protect whole home and keep your children safe. Now once those filters are installed, it should not be the case that technically literate children can just flick the filters off at the click of a mouse without anyone knowing. So we have agreed with the industry that those filters can only be changed by the account holder, who has to be an adult.

So an adult has to be engaged in the decisions. But of course, all this just deals with the ‘flow’ of new customers, those switching service providers or buying an Internet connection for the first time. It does not deal with the huge ‘stock’ of existing customers, almost 19 million households, so this is now where we need to set our sights.

Following the work we’ve already done with the service providers, they have now agreed to take a big step. By the end of next year, they will have contacted all of their existing customers, and presented them with an unavoidable decision about whether or not to install family friendly content filters. TalkTalk, who have shown great leadership on this, have already started and are asking existing customers as I speak.

We are not prescribing how the ISPs should contact their customers, it’s up to them to find their own technological solutions. But however they do it, there will be no escaping this decision, no ‘remind me later’ and then it never gets done. And they will ensure it is an adult making the choice. If adults don’t want these filters — that’s their decision. But for the many parents who would like to be prompted or reminded, they’ll get that reminder, and they’ll be shown very clearly how to put on family friendly filters.

This is a big improvement on what we had before, and I want to thank the service providers for getting on board with this.

But let me be clear: I want this to be a priority for all Internet service providers not just now, but always. That’s why I am asking today for the small companies in the market to adopt this approach too, and why I’m asking OFCOM, the industry regulator, to oversee this work, judge how well the ISPs are doing and report back regularly. If they find that we are not protecting children effectively I will not hesitate to take further action.

But let me also just say this: I know there are lots of charities and other organisations which provide vital online advice and support that many young people depend on. And we need to make sure that the filters do not — even unintentionally — restrict this helpful and often educational content. So I will be asking the UK Council for Child Internet Safety to set up a working group to ensure that this doesn’t happen, as well as talking to parents about how effective they think the filter products are. So making filters work is one front we are acting on; the other is education.

In the new national curriculum, launched just a couple of weeks ago, there are unprecedented requirements to teach children about online safety.

That doesn’t mean teaching young children about pornography, it means sensible, age-appropriate education about what to expect on the Internet. We need to teach our children, not just about how to stay safe online, but how to behave online too. On social media and over phones with their friends. And it’s not just children that need to be educated, but parents.

People of my generation grew up in a completely different world, our parents kept an eye on us in the world they could see. This is still a relatively new, digital landscape — a world of online profiles and passwords — and speaking as a parent, most of us need help navigating it. Companies like Vodafone already do a good job at giving parents advice about online safety. They spend millions on it and today they are launching the latest edition of their digital parenting guide. They are also going to publish a million copies of a new educational tool for younger children called the Digital Facts of Life.

And I am pleased to announce something else today: a new, major national campaign that’s going to be launched in the new year, that is being backed by the four major internet service providers as well as other child-focused companies, that will speak directly to parents about how to keep their children safe online, and how to talk to their children about other dangers like sexting and online bullying.

Government is going to play its part too.

We get millions of people interacting with government, whether that’s sorting out their road tax, on their Twitter account or — soon — registering for Universal Credit.

I have asked that we use these interactions to keep up the campaign, to prompt parents to think about filters, and to let them know how they can keep their children safe online.

This is about all of us playing our part.

So we’re taking action on how children access this stuff, on how they’re educated about it, and I can tell you today we are also taking action on the content that is online.

There are certain types of pornography that can only be described as ‘extreme’.

I am talking particularly about pornography that is violent, and that depicts simulated rape. These images normalise sexual violence against women – and they are quite simply poisonous to the young people who see them.

The legal situation is that although it’s been a crime to publish pornographic portrayals of rape for decades, existing legislation does not cover possession of this material – at least in England and Wales.

Possession of such material is already an offence in Scotland, but because of a loophole in the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008, it is not an offence South of the border. Well I can tell you today we are changing that.

We are closing the loophole — making it a criminal offence to possess internet pornography that depicts rape. And we are doing something else to make sure that the same rules apply online as they do offline. There are some examples of extreme pornography that are so bad that you can’t even buy this material in a licensed sex shop.

And today I can announce we will be legislating so that videos streamed online in the UK are subject to the same rules as those sold in shops.

Put simply – what you can’t get in a shop, you will no longer be able to get online. Everything I’ve spoken about today comes back to one thing: the kind of society we want to be. I want Britain to be the best place to raise a family.

A place where your children are safe.

Where there’s a sense of right and wrong, and boundaries between them.

Where children are allowed to be children.

All the actions we’re taking come back to that.

Protecting the most vulnerable in our society; protecting innocence; protecting childhood itself.

That is what is at stake.

And I will do whatever it takes to keep our children safe.

22 Jul 2013 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society, United Kingdom

Technology writer and broadcaster Bill Thompson spoke at the recent ISPA Awards dinner. ISPA, the Internet Service Providers Association, represents the companies that connect us all to the Net, and Thompson called on them to stand up for freedom, however hard that may be. This is an edited version of his talk.

I first used the internet in 1984/5 when I was a student at Cambridge University sitting at a dumb terminal on an IBM mainframe and discovered that we could email people both locally and at other universities. I didn’t know we were using the Internet, of course, because it was just ‘the network’. I had access when I worked at Acorn Computers, and in the early 1990’s ended up at PIPEX, the UK’s first commercial ISP.

A lot of my work at that time revolved around promoting the idea that the Internet was the right way to build the ‘information superhighway’ beloved of Al Gore, Tony Blair and others, rather than closed, proprietary technologies like AOL, Compuserve and the Microsoft Network. These systems were touted as the alternative to the insecure, unmanageable internet, and for a brief period it looked like they might triumph simply because of the marketing effort that went into them, but in the end it was the open net and the open web that came to provide the infrastucture for our networked economies and society.

In the last three decades the internet has become the pipe that delivers the world to us in all the ways that radio and TV used to and all the ways that radio and TV, as one-way broadcast media, never could. These days there are many countries where it makes far more sense to occupy the offices of the ISPs after a military coup than it does to take over the television stations.

This triumph comes at a cost. We have managed to avoid replacing the cacophony of the somewhat democratic open standards bazaar with a closed-minded architecture of control in which we would be expected to ask for permission to do anything, and would be reliant on Microsoft, AOL and those who they approve to maintain, develop and deliver innovation, and to charge what they liked for the privilege, but in the process we have built an internet that is almost impossible to manage.

We see it in the chaos of spam, malware and phishing, as well as the impossibility of creating effective filters for material that we’d prefer our children didn’t see, whatever the government may want to believe (and whatever PR hype they may persuade the Daily Mail to print). Many ISPs would probably prefer a safe, manageable network where they can control what their customers see and do and avoid takedown notices and copyright trolls and excessive legislation to manage illegal and ‘harmful’ content online. We know what that world looks like – it’s the content industries dream of compulsory digital rights management, premium services and Ultraviolet, but it doesn’t look that attractive to those of us who value the Internet’s creative potential and see it as the foundation of an open society.

We inherited a network which was designed to be open and permissive and to be used by nice people doing nice things. Over the last three decades it has been unleashed onto the world, and the openness of the network has meant that bad people have used it to do bad things, selfish people have used it to do selfish things, and governments have looked for ways to monitor it using the same features that the authors of Tor used to make it hard to monitor.

As a result today’s internet is more easily used for oppression than openness, and have seen how the US and UK, like China and others, have been reading as much net traffic as they can get their hands on, and how laws have been written to make such surveillance legal. The latest announcements on filtering mark a move towards deeper monitoring of the material UK net users are downloading, using the argument that we must ‘think of the children’ to justify this.

It may mark the point at which many ordinary users start to worry that the network they increasingly rely on for many aspects of their daily life is in fact the space in which they are most exposed, where their freedom to live their lives without being observed or suspected is most easily removed, because it is just as impossible to enforce the positive freedoms online as the negative ones. We can’t keep people safe from malware or spam, and we can’t tell them they can speak privately or speak openly without fear of reprisal.

ISPs have a real problem here. It’s the one outlined by Tim Wu and Jack Goldsmith in their book ‘Who Controls the Internet?’, where they point out that whatever freedom we may seek online, the net is delivered to us by companies that have offices and employees and servers, all of which are located in the physical world. For a company to operate within a territory it has to obey the laws within that territory, and while it seems to be accepted that there’s some wriggle room over how ISPs manage their tax affairs, disobeying court orders – especially secret ones – is generally seen as being a bad idea. Their lawyers don’t like it. Their families wouldn’t like having to say goodbye as senior executives were whisked off to gaol.

Yet these ISPs have become the de facto guardians of our online freedoms. They are the people who built the networks on which the world now runs, and the choices they make about standards, systems, hardware, traffic shaping, pricing plans and who gets to put tapping equipment in their routing cabinets matter.

The only viable solution I can see is to work with ISPs to re-engineer the network so that it cannot be so easily subverted by the forces of oppression and control that would close the networks, close society and close our imagination. We created the internet, it is a product of our imagination and our engineering skill and there is very little about it that could not be re-engineered – if we cared enough to do it, and there are no laws that we cannot change to ensure that the regulation of that re-engineered network preserves our freedoms and does not remove them.

If we want the network to be a tool for freedom then we need to design it in the right way, not simply work with what we have inherited.

Our last, best, hope? Metafilter tells me the phrase was coined by Lincoln but used in Bablyon 5 :-)

Further reading

• Larry Lessig on Rewriting the Internet

• Marco Ament on Lockdown

• Adactio on APIs

• Anil Dash on the Web we Lost

• Tim Wu & Jack Goldsmith: Who Controls the Internet?