28 Mar 2018 | Event Reports, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

“We must distinguish the things that are intellectually dishonest and aimed at persuading, which is traditionally called propaganda, and the things where people are trying to give you general information, which doesn’t have the absolute intention of persuading you,” said The Times columnist David Aaronovitch at a panel at the Essex Book Festival.

Aaronovitch, also Index’s chair, was discussing the role of propaganda with leading expert on the darknet and technology Jamie Bartlett and Chinese-British author Xinran, who was the first woman to have a late-night radio show in China.

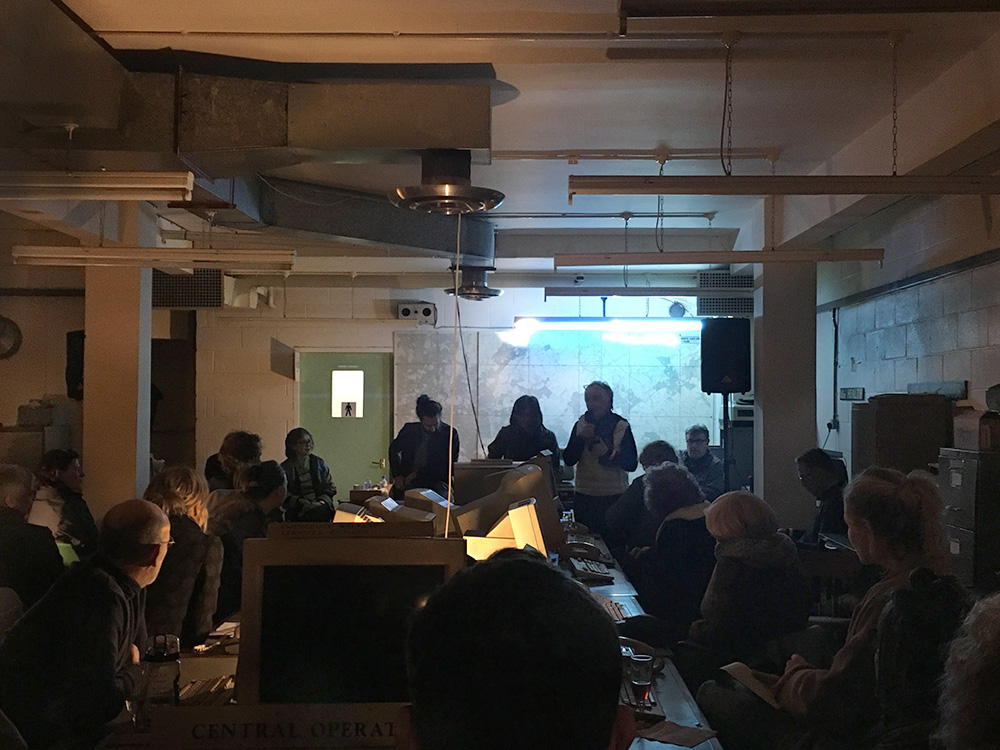

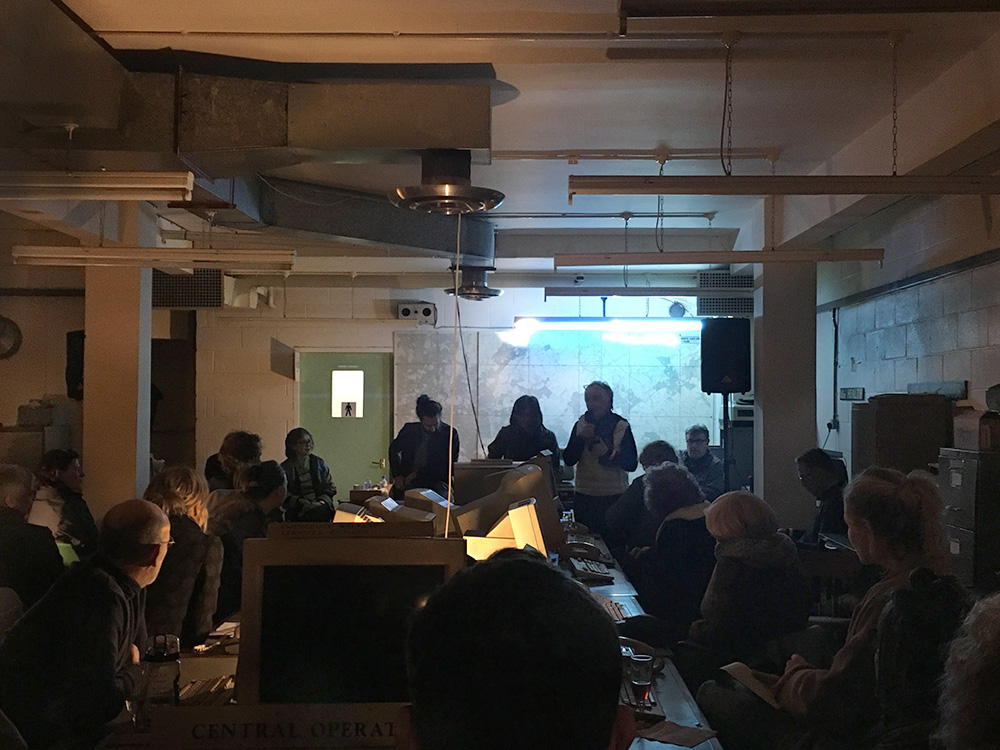

The panel, chaired by Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley, was part of the festival’s Nuclear Option day at the Kelvedon Hatch Secret Nuclear Bunker, a twisted network of dimly lit hallways and musty rooms that lie beneath a field.

Around 75 attendees gathered on March 25 to listen to Index’s panel and attend other workshops, screenings and performances part of the festival. Everyone at the festival was free to roam the enormous bunker and walk amongst Cold War history.

Passing signs that instructed people to “use water sparingly” and dusty machines that co-ordinated evacuation procedures, attendees eventually made their way to a desk-lamp lit room and were seated at long desks with old, monochrome computers.

Looking at the current state of propaganda, Bartlett said “everything has become more emotional and gut-driven,” adding that politics has not become as informed as people had hoped, but now become “heuristic because people are just showered with information”.

Aaronovitch called the inundation of information the “age of cacophony”.

What is emerging, according to Bartlett, is a “horrible new form of soft surveillance that has encouraged a great conformity among people”.

Xinran said China’s current propaganda, especially on social media, along with party control of education and the legal system has led to “one voice” in China, despite age gaps, class, education and geographical residence.

The author talked about her past experiences with censorship and Chinese propaganda when she worked on her radio show in China. She explained that there was a list of restrictions she had to abide by, these included never mentioning the British media, Western religions or love and relationships. The author said during her show she was able to tackle subjects that were previously taboos on Chinese radio.

“My work was stopped for three months when I spoke about homosexuality,” said Xinran. “This type of censorship was very strong until 1997, but it has now escalated to constant censorship, due to social media.”

Looking at the future of propaganda and its direction, Bartlett added that he can “see much more reliance on coercive digital types of surveillance being absolutely necessary just to maintain some type of law and order in society, especially online, which could make us a much more authoritarian society”.

This led Bartlett to predict that “already authoritarian countries are going to become much more so, and already very free countries are going to become even more free to the point where it might collapse”.

He believes we are shifting to a “Huxleyan society,” which Aaronovitch called the “algorithmic society”. Both felt one big question was, who governs the algorithms?

Aaronovitch noted that it depended on who was controlling the algorithms, saying that if the EU requested that Google to reveal its algorithms, it would be problematic; however, governmental algorithms used for policing in a democratic society were essential.

With reference to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which was mentioned numerous times during the panel, Bartlett noted that the worry over “Cambridge Analytica’s 5,000 data points on every single American doesn’t compare to what’s coming”.

“We are going to be creating a lot more data in the future,” said Bartlett. “And it is going to be shared and it is going to be used by political actors.”

Aaronovitch advised the audience that the best way to combat propaganda is to ask yourself, “‘Am I wrong?’. The point is to ensure no one is “completely blinded by initial preferences”.

Similar to Aaronovitch’s warning to predisposed biases, Xinran calls for “independent thinking,” and equated the consumption of information with eating.

“In Chinese we say you become what you eat,” said Xinran. “And your brain is the same way. You become what you are by what you believe”.

Hats off to @EssexBookFest! An incredible day at the Secret Nuclear Bunker. Brilliant discussion with @IndexCensorship, @JamieJBartlett, @DAaronovitch, @londoninsider and #Xinran, topped off with a silent disco of music banned from Estonia, with obligatory gherkins and vodka 👍 pic.twitter.com/HVtfrVDRb1 — Radical ESSEX (@RadicalEssex) 26 March 2018

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522237614911-7109bbff-bdcf-1″ taxonomies=”2631″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

25 Aug 2017 | Digital Freedom, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

I spend a lot of my time writing about encryption. Until recently I did this from a UK perspective. That is to say, in a country where there are pretty good citizen protections. Despite the occasional hysterical article, the police don’t snoop on you without having some probable cause and a legal warrant. UK citizens aren’t constantly under surveillance and don’t get rounded up for speaking their mind.

From this vantage point, the public debate on encryption starts with its problems. Terrorists are using encrypted messaging apps. Drug dealers are using the Tor browser. End-to-end encryption used by the big tech firms is a headache for local police forces. All this is true. But any benefits are merely addendum, secondary points, “ands” or “buts”. Don’t forget, however, that encryption is also for activists and journalists, including those in less friendly parts of the world. Oh, and don’t forget ordinary citizens. Such benefits are mostly discussed abstractly, almost as an afterthought.

My view on encryption changed in 2016 when I was researching my book Radicals. This being a book about fringe political movements – often viewed with hostility by governments – I expected to use some degree of caution. But it was more than this. Over in Croatia, I was following Vit Jedlicka, the president of Liberland, a libertarian pseudo-nation on the Serb-Croat border. Jedlicka is trying to create a new nation on some unclaimed land that will run according to the principles of radical libertarianism, including voluntary taxation. The Croat authorities do not like him at all, even though he is non-violent and law abiding.

I arrived in Croatia, after an early Easy Jet flight, and was taken aside for questioning by the border police, who appeared to know I was coming. They told me not to attempt to visit Liberland. A little later, while I was away from my hotel, the police turned up and demanded a copy of my passport from the hotel manager. Jedlicka, meanwhile, was barred from entering Croatia, having been deemed a threat to national security.

I did not know a great deal about the Croatian police, but what little I did know made me doubt they cared too much about my right to privacy. I suddenly felt exposed. So Jedlicka and I communicated using an encrypted messaging app, Signal. I had considered Signal mostly a frustrating tool that helps violent Islamists avoid intelligence agencies. But suddenly this nuisance app was transformed. Thank God for Signal, I thought. Whoever invented Signal deserved a prize, I thought. Without Signal, Jedlicka couldn’t engage in activism. Without Signal, I couldn’t write about it.

This was in Croatia. Imagine what that might feel like as a democratic activist in Iran, Russia, Turkey or China.

You see the debate about encryption differently once you’ve had cause to rely on it personally for morally sound purposes. An abstract benefit to journalists or activists becomes a very tangible, almost emotional dependence. The simple existence of powerful, reliable encryption does more than just protect you from an overbearing state: it changes your mindset too. When it’s possible to communicate without your every move being traced, the citizen is emboldened. He or she is more likely to agitate, to protest and to question, rather than sullenly submit. If you believe the state is tracking you constantly, the only result is timid, self-censoring, frightened people. I felt it coming on in Croatia. Governments should be afraid of the people, not the other way around.

The debate on encryption, therefore, should change. The people who build this stuff – whether Tor, PGP or whatever else – are generally motivated by the desire to help people like Jedlicka, people like me. They don’t do it for the terrorists. Seen and understood in that light, the starting point for discussion is about the great benefits of encryption, followed by the frustrating and inevitable fact that bad guys will use the same networks, browsers and messaging apps.

Which is why any efforts to undermine encryption – through laws, endless criticism, weakening standards, bans, threats to ban, backdoors and international agreements – would hit someone like Jedlicka, or me, just as it would Isis. The questions then become: are we willing to prevent good guys having protection just because bad guys are using it? Once you’ve had cause to use it yourself, the answer is extremely clear.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1503654311600-41f8449d-cfd3-2″ taxonomies=”6914″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

28 May 2015 | News and features, United Kingdom

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

It’s hard not to feel sorry for Abu Haleema. The poor man can’t catch a break. All he wants to do is establish a global caliphate under the harshest possible interpretation of sharia — a caliphate in which, he hopes, he will play a significant role — and yet he is thwarted at every turn.

First the authorities stop him from travelling to Syria to join the Islamic State. And then, to add insult to injury, they take away his internet, like he’s a naughty teenager. It’s a hard knock life for Abu.

And it’s about to get even harder. In the Queen’s Speech, the government announced a new counter-extremism bill which, will essentially make the existences of Abu Haleema and people like him illegal, without actually making them illegal.

How does that work? To quote the BBC: “The legislation will also propose the introduction of banning orders for extremist organisations who use hate speech in public places, but whose activities fall short of proscription.”

This, in essence, is a thought ASBO, a convenient way of stamping out “extremism” without making any serious attempt to test that behaviour against any kind of proper harm principle.

Whether we like it or not, we do have laws on hate speech and incitement to violence in the United Kingdom. We also have the powers to proscribe terrorist organisations.

But these powers are apparently not enough: and so we must create semi-legal sub-strata of behaviour where people can be censored on the basis of us not liking what they say very much.

This is not some plea for accommodation of the views of Abu Haleema and his friends. Let us be very clear here: these are views which are entirely antithetical to the secular liberal democracy we aspire to be.

But that fact is exactly the test of a secular liberal democracy: if we are to imagine free speech as a defining value of democracy (as David Cameron has said he does) then we cannot just choose which free speech we will defend and which we will not (as David Cameron has said he wants to). As commentator Jamie Bartlett has pointed out, free speech is not something that one pledges allegiance to in the abstract while stifling in the practice.

Predictably, we now turn to the life and times of George Orwell for a lesson from history.

In early 1945, a small group of London anarchists found themselves facing prosecution for undermining the war effort — specifically the charge of “causing disaffection among the troops”. Their crime was to criticise basic training, and to suggest that Belgian resistance movements should not hand over weapons to their Allied liberators, but instead retain their arms and set about building workers’ militias which would form a revolutionary force in post-Nazi Europe.

For this, several of the group were jailed, the British authorities of the time not noticing the irony of fighting for freedom in Europe while jailing dissidents at home.

The failure of the state — and the civil liberties movement — to stand for the right to free speech led to the formation of the Freedom Defence Committee.

Most of the supporters of the Freedom Defence Committee, including Orwell, would have had some sympathy with the anarchist position (Orwell had hoped, in the early days of the war, that the training and arming of the Home Guard would lead to a socialist revolution after the Nazis had been defeated. Apart from that, at least one of the accused, Vernon Richards, was a friend of Orwell’s).

But Orwell and his comrades in the Freedom Defence Committee were alert to the fact that one cannot simply defend the freedom of one’s friends. One also had to stand for the rights of communists and even fascists to hold their views. (Before any reader attempts to refer me to Orwell’s supposedly infamous “list” of communists and fellow travellers, supplied to his friend Celia Kirwan at the government’s Information Research Department, let me point out that it was a list compiled as a favour for a friend, not a blacklist: no one on that list was ever arrested, and they pursued their careers and lives unhindered). This led to the FDC taking the position that those with unpopular views – even those who had been (and still were) on the other side in the war, should be given the same justice as everyone else – demanding, for example, proper rights in cases of dismissal from employment when such a concept barely existed for anyone.

Fascists, communists and Islamists aside, there is probably not a single political grouping in Britain today that does not lay some claim to Orwell’s legacy. But as with free speech arguments, all tend to support the side that supports their side: libertarians cling to the anti-surveillance overtones in his work, while ignoring the long-held demands for state intervention on some issues. Conservatives admire the anti-communism, while ignoring the horror at capitalism, tradition, and the class system. Socialists pretend that Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm were anything else apart from scathing attacks on left utopianism.

Orwell was a far from perfect figure, but he did get a lot of things right — the fundamental one being the consistent application of principles on issues of liberty.

It is fashionable to invoke Big Brother whenever governments introduce new surveillance measures, or suggest censorship of extremist views. It is also, generally, silly and hyperbolic. But when faced with an enemy entirely at odds with democracy, as we are with Islamist extremism, it’s worth noting that, as did Orwell and his comrades, it is possible to attack the ideology while standing firm on freedom.

An earlier version of this article stated that a group of London anarchists faced prosecution for suggesting the Belgian resistance movements should not hand over weapons to their German liberators. This has been corrected.

This column was posted on 28 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

12 Feb 2015 | Digital Freedom, mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

In his new ebook, tech expert Jamie Bartlett describes what he sees as the long-term ‘Snowden effect’: the explosion of new ways to keep online secrets and protect privacy, and the challenges that presents for state security services. In this extract, Bartlett uncovers some of the more revolutionary plans in the privacy pipeline.

Motivated by an honourable desire to protect online freedom and privacy, hundreds of computer scientists and internet specialists are working on ingenious ways of keeping online secrets, preventing censorship, and fighting against centralised control. A veritable army motivated by a desire for privacy and freedom, trying to wrestle back control for ordinary people. This is where the long-term effects will be felt.

Soon there will be a new generation of easy-to-use, auto-encryption internet services. Services such as MailPile, and Dark Mail – email services where everything is automatically encrypted. Then there’s the Blackphone – a smart phone that encrypts and hides everything you’re doing. There are dozens – hundreds, perhaps – of new bits of software and hardware like this that cover your tracks, being developed as you read this – and mainly by activists motivated not by profit, but by privacy. Within a decade or so I think they will be slick and secure, and you won’t need to be a computer specialist to work out how they work. We’ll all be using them.

And there are even more revolutionary plans in the pipeline. An alternative way of organising the internet is being built as we speak, an internet where no one is in control, where no one can find you or shut you down, where no one can manipulate your content. A decentralised world that is both private and impossible to censor.

Back in 2009, in an obscure cryptography chat forum, a mysterious man called Satoshi Nakamoto invented the crypto-currency Bitcoin.* It turns out the real genius of Bitcoin was not the currency at all, but the way that it works. Bitcoin creates an immutable, unchangeable public copy of every transaction ever made by its users, which is hosted and verified by every computer that downloads the software. This public copy is called the ‘blockchain’. Pretty soon, enthusiasts figured out that the blockchain system could be used for anything. Armed with 30,000 Bitcoins (around $12 million) of crowdfunded support, the Ethereum project is dedicated to creating a new, blockchain-operated internet. Ethereum’s developers hope the system will herald a revolution in the way we use the net – allowing us to do everything online directly with each other, not through the big companies that currently mediate our online interaction and whom we have little choice but to trust with our data.

Already others have applied this principle to all sorts of areas. One man built a permanent domain name system called Namecoin; another an untraceable email system call Bitmessage.

Perhaps the most interesting of all is a social media platform called Twister, a version of Twitter that is completely anonymous and almost impossible to censor. Miguel Freitas, the Brazilian who spent three months building it, tells me he was sparked into action when he read that David Cameron had considered shutting down Twitter after the 2011 riots. ‘The internet alone won’t help information flow,’ Freitas says, ‘if all the power is in the hands of a few people.’

This trend towards decentralised, encrypted systems has become an important aspect of the current crypto-wars.† MaidSafe is a UK start-up that, in a similar way, wants to redesign the internet infrastructure towards a peer-to-peer communications network, without centralised servers. Its developers are building a network made up of contributing computers, with each one giving up a bit of its unused hard drive. You access the network, and the network accesses the computers. Everything is encrypted, and data is stored across the entire network, which makes hacking or spying extremely difficult, if not impossible.

Nick Lambert, the Chief Operating Officer for MaidSafe, explained to me the vision. When you open a browser and surf the web it might feel like a seamless process, but there are all manner or rules and systems that clutter up the system: domain name servers, company servers, routing protocols, security protocols. This is the stuff that keeps the internet going: rules that route your request for traffic, servers that host that web page you’re after, systems that certify for your computer that the site you’re trying to access isn’t bogus. Because it all happens at the speed of light, it doesn’t feel cluttered up, of course.

But all these little stages and protocols create invisible centres of power, explains Nick – be they governments, big tech companies or invisible US-based regulators – and they are all exercising control over what happens on the net. That’s bad for security, and bad for privacy. MaidSafe strips all this out. The end result, says Nick, will be a network that is very difficult to censor and offers more privacy. ‘Even if we wanted to censor users’ content, we couldn’t – because with this system we don’t know or have access to anything the users do.

They’re in control.’ Nick accepts some people will misuse it – but that’s true of almost any technology. ‘Kitchen knives can cause harm,’ he says, ‘but you wouldn’t ban kitchen knives.’

As I see it, this powerful combination of public appetite and new technology means staying hidden online will become easier and more sophisticated. It might feel unlikely at a time when every click and swipe is being collected by someone somewhere, but in the years ahead, it will be harder for external agencies to monitor or collect what we share and see; and censorship will become far more difficult. A golden age of privacy and freedom. Perhaps.

* You’ve probably heard of this pseudonymous digital cash because it was, and still is, the currency of choice on the illegal online drugs markets.

† And increasingly, I predict, politics. Although no political parties – save the occasional fringe party – have given any thought to what crypto-currencies might mean. What does a modern centre-left party think of crypto-currency, or of blockchain decentralisation? They have no idea.

@JamieJBartlett is the director of Centre for the Analysis of Social Media, Demos and a tech blogger for @telegraph.

This extract was published on 12 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org with the author’s permission.