Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

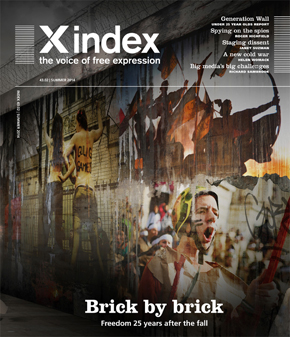

This article is part of the summer 2014 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by Jason DaPonte, on privacy on the internet taken from the summer 2014 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend the Privacy in the digital age session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

“Government may portray itself as the protector of privacy, but it’s the worst enemy of privacy and that’s borne out by the NSA revelations,” web and privacy guru Jeff Jarvis tells Index.

Jarvis, author of Public Parts: How Sharing in the Digital Age Improves the Way We Work and Live argues that this complacency is dangerous and that a debate on “publicness” is needed. Jarvis defines privacy “as an ethic of knowing someone else’s information (and whether sharing it further could harm someone)” and publicness as “an ethic of sharing your own information (and whether doing so could help someone)”.

In his book Public Parts and on his blog, he advocates publicness as an idea, claiming it has a number of personal and societal benefits including improving relationships and collaboration, and building trust.

He says in the United States the government can’t open post without a court order, but a different principle has been applied to electronic communications. “If it’s good enough for the mail, then why isn’t it good enough for email?”

While Jarvis is calling for public discussion on the topic, he’s also concerned about the “techno panic” the issue has sparked. “The internet gives us the power to speak, find and act as a [single] public and I don’t want to see that power lost in this discussion. I don’t want to see us lose a generous society based on sharing. The revolutionaries [in recent global conflicts] have been able to find each other and act, and that’s the power of tech. I hate to see how deeply we pull into our shells,” he says.

The Pew Research Centre predicts that by 2025, the “internet will become like electricity – less visible, yet more deeply embedded in people’s lives for good and ill.” Devices such as Google Glass (which overlays information from the web on to the real world via a pair of lenses in front of your eyes) and internet-connected body monitoring systems like, Nike+ and Fitbit, are all examples of how we are starting to become surrounded by a new generation of constantly connected objects. Using an activity monitor like Nike+ means you are transmitting your location and the path of a jog from your shoes to the web (via a smartphone). While this may not seem like particularly private data, a sliding scale emerges for some when these devices start transmitting biometric data, or using facial recognition to match data with people you meet in the street.

As apps and actions like this become more mainstream, understanding how privacy can be maintained in this environment requires us to remember that the internet is decentralised; it is not like a corporate IT network where one department (or person) can switch the entire thing off through a topdown control system.

The internet is a series of interconnected networks, constantly exchanging and copying data between servers on the network and then on to the next. While data may take usual paths, if one path becomes unavailable or fails, the IP (Internet Protocol) system re-routes the data. This de-centralisation is key to the success and ubiquity of the internet – any device can get on to the network and communicate with any other, as long as it follows very basic communication rules.

This means there is no central command on the internet; there is no Big Brother unless we create one. This de-centralisation may also be the key to protecting privacy as the network becomes further enmeshed in our everyday lives. The other key is common sense. When asked what typical users should do to protect themselves on the internet, Jarvis had this advice: “Don’t be an idiot, and don’t forget that the internet is a lousy place to keep secrets. Always remember that what you put online could get passed around.”

As the internet has come under increasing control by corporations, certain services, particularly on the web, have started to store, and therefore control, huge amounts of data about us. Google, Facebook, Amazon and others are the most obvious because of the sheer volume of data they track about their millions of users, but nearly every commercial website tracks some sort of behavioural data about its users. We’ve allowed corporations to gather this data either because we don’t know it’s happening (as is often the case with cookies that track and save information about our browsing behaviour) or in exchange for better services – free email accounts (Gmail), personalised recommendations (Amazon) or the ability to connect with friends (Facebook).

“A transaction of mutual value isn’t surveillance,” Jarvis argues, referencing Google’s Priority Inbox (which analyses your emails to determine which are “important” based on who you email and the relevance of the subject) as an example. He expands on this explaining that as we look at what is legal in this space we need to be careful to distinguish between how data is gathered and how it is used. “We have to be very, very careful about restricting the gathering of knowledge, careful of regulating what you’re allowed to know. I don’t want to be in a regime where we regulate knowledge.”

Sinister or not, the internet giants and those that aspire to similar commercial success find themselves under continued and increasing pressure from shareholders, marketers and clients to deliver more and more data about you, their customers. This is the big data that is currently being hailed as something of a Holy Grail of business intelligence. Whether we think of it as surveillance or not, we know – at least on some level – that these services have a lot of our information at their disposal (eg the contents of all of our emails, Facebook posts, etc) and we have opted in by accepting terms of service when we sign up to use the service.

“The NSA’s greatest win would be to convince people that privacy doesn’t exist,” says Danny O’Brien, international director of the US-based digital rights campaigners Electronic Frontier Foundation. “Privacy nihilism is the state of believing that: ‘If I’m doing nothing wrong, I have nothing to hide, so it doesn’t matter who’s watching me’.”

This has had an unintended effect of creating what O’Brien describes as “unintentional honeypots” of data that tempt those who want to snoop, be it malicious hackers, other corporations or states. In the past, corporations protected this data from hackers who might try to get credit card numbers (or similar) to carry out theft. However, these “honeypot” operators have realised that while they were always subject to the laws and courts of various countries, they are now also protecting their data from state security agencies. This largely came to light following the alleged hacking of Google’s Gmail by China. Edward Snowden’s revelations about the United States’ NSA and the UK’s GCHQ further proved the extent to which states were carrying out not just targeted snooping, but also mass surveillance on their own and foreign citizens.

To address this issue, many of the corporations have turned on data encryption; technology that protects the data as it is in transit across the nodes (or “hops”) across the internet so that it can only be read by the intended recipient (you can tell if this is on when you see the address bar in your internet browser say “https” instead of “http”). While this costs them more, it also costs security agencies more money and time to try to get past it. So by having it in place, the corporations are creating a form of “passive activism”.

Jarvis thinks this is one of the tools for protecting users’ privacy, and says the task of integrating encryption effectively largely lies with the corporations that are gathering and storing personal information.

“Google thought that once they got [users’ data] into their world it was safe. That’s why the NSA revelations are shocking. It’s getting better now that companies are encrypting as they go,” he said. “It’s become the job of the corporations to protect their customers.”

Encryption can’t solve every problem though. Codes are made to be cracked and encrypted content is only one level of data that governments and others can snoop on.

O’Brien says the way to address this is through tools and systems that take advantage of the decentralised nature of the internet, so we remain in control of our data and don’t rely on third party to store or transfer it for us. The volunteer open-source community has started to create these tools.

Protecting yourself online starts with a common-sense approach. “The internet is a lousy place to keep a secret,” Jarvis says. “Once someone knows your information (online or not), the responsibility of what to do with it lies on them,” says Jarvis. He suggests consumers be more savvy about what they’re signing up to share when they accept terms and conditions, which should be presented in simple language. He also advocates setting privacy on specific messages at the point of sharing (for example, the way you can define exactly who you share with in very specific ways on Google+), rather than blanket terms for privacy.

Understanding how you can protect yourself first requires you to understand what you are trying to protect. There are largely three types of data that can be snooped on: the content of a message or document itself (eg a discussion with a counsellor about specific thoughts of suicide), the metadata about the specific communication (eg simply seeing someone visited a suicide prevention website) and, finally, metadata about the communication itself that has nothing to do with the content (eg the location or device you visited from, what you were looking at before and after, who else you’ve recently contacted).

You can’t simply turn privacy on and off – even Incognito mode on Google’s Chrome browser tells you that you aren’t really fully “private” when you use it. While technologies that use encryption and decentralisation can help protect the first two types of content that can be snooped on (specific content and metadata about the communication), there is little that can be done about the third type of content (the location and behavioural information). This is because networks need to know where you are to connect you with other users and content (even if it’s encrypted). This is particularly true for mobile networks; they simply can’t deliver a call, SMS or email without knowing where your device is.

A number of tools are on the horizon that should help citizens and consumers protect themselves, but many of them don’t feel ready for mainstream use yet and, as Jarvis argues, integrating this technology could be primarily the responsibility of internet corporations.

In protecting yourself, it is important to remember that surveillance existed long before the internet and forms an important part of most nation’s security plans. Governments are, after all, tasked with protecting their citizens and have long carried out spying under certain legal frameworks that protect innocent and average citizens.

O’Brien likens the way electronic surveillance could be controlled to the way we control the military. “We have a military and it fights for us…, which is what surveillance agencies should do. The really important thing we need to do with these organisations is to rein them back so they act like a modern civilised part of our national defence rather than generals gone crazy who could undermine their own society as much as enemies of the state.”

The good news is that the public – and the internet itself – appear to be at a junction. We can choose between a future where we can take advantage of our abilities to self-correct, decentralise power and empower individuals, or one where states and corporations can shackle us with technology. The first option will take hard work; the second would be the result of complacency.

Awareness of how to protect the information put online is important, but in most cases average citizens should not feel that they need to “lock down” with every technical tool available to protect themselves. First and foremost, users that want protection should consider whether the information they’re protecting should be online in the first place and, if they decide to put it online, should ensure they understand how the platform they’re sharing it with protects them.

For those who do want to use technical tools, the EFF recommends using ones that don’t rely on a single commercial third party, favouring those that take advantage of open, de-centralised systems (since the third parties can end up under surveillance themselves). Some of these are listed (see box), most are still in the “created by geeks for use by geeks” status and could be more user-friendly.

Privacy protectors

TOR

This tool uses layers of encryption and routing through a volunteer network to get around censorship and surveillance. Its high status among privacy advocates was enhanced when it was revealed that an NSA presentation had stated that “TOR stinks”. TOR can be difficult to install and there are allegations that simply being a TOR user can arouse government suspicion as it is known to be used by criminals. http://www.torproject.org

OTR

“Off the Record” instant messaging is enabled by this plugin that applies end-to-end encryption to other messaging software. It creates a seamless experience once set up, but requires both users of the conversation to be running the plug-in in order to provide protection. Unfortunately, it doesn’t yet work with the major chat clients, unless they are aggregated into yet another third party piece of software, such as Pidgin or Adium. https://otr.cypherpunks.ca/

Disconnect

This browser plugin tries to put privacy control into your hands by making it clear when internet tracking companies or third parties are trying to watch your behaviour. Its user-friendly inter- face makes it easier to control and understand. Right now, it only works on Chrome and Firefox. http://www.disconnect.me

Silent Circle

This is a solution for encrypting mobile communications – but only works between devices in the “silent circle” – so good for certain types of uses but not yet a mainstream solution, as encryption wouldn’t extend to all calls and messages that users make. Out-of-circle calls are currently only available in North America. https://silentcircle.com

©Jason DaPonte and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the summer 2014 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine, with a special report on propaganda and war. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.