11 Dec 2010 | Uncategorized

Julian Assange’s lawyers are saying that a US indictment is imminent. But what crime would he actually be guilty of? The Congressional Research Service pointed out earlier this week, in a fascinating document published on Steven Aftergood’s always enlightening Secrecy News, just how difficult it would be to nail him.

Past prosecutions have been almost entirely of individuals who have access to classified information and leak it to foreign agents (not to the press for publication).

And there are no cases of publishers being prosecuted. There have been calls for Assange’s prosecution under the Espionage Act, which covers the leaking of documents relating to the US’s national defence. Yet although some of the diplomatic cables would fit that category, it is not illegal to disclose the information unless you are a government employee.

The US government would have to prove that Assange was disseminating documents with intent to harm the US’s national security — and here, once again, the act of publishing the documents is unlikely to be an offence and would be protected by the First Amendment.

The Supreme Court has been wary in the past of using the Espionage Act to punish whistleblowers “who reveal information that poses more of a danger of embarrassing public officials than of endangering national security”.

Extradition would also be immensely complex, not least because it is not allowed when the offence is political.

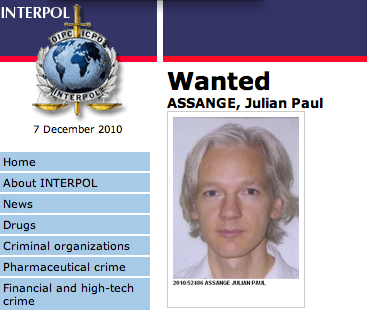

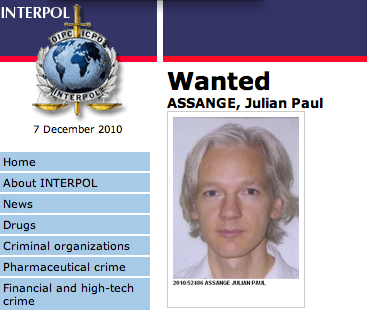

7 Dec 2010 | News

A London court today refused to grant bail to Wikileaks’ founder Julian Assange. Assange is facing extradition to Sweden on sexual assault charges including one count of unlawful coercion, two counts of sexual molestation and one count of rape.

(more…)

6 Dec 2010 | Index Index, minipost, News

Wikileaks is reporting that Swiss bank Post Finance has frozen an account set up for the legal defence of Julian Assange. The move follow’s Paypal’s freezing of Wikleaks’ account last Friday (3 December)

Read Wikileaks’ statement here

6 Dec 2010 | Uncategorized

Imagine if an American politician had called for the execution of the editor of the New York Times.

Or if the newspaper’s bank had declined to handle its business any more because it considered that it had published information that promoted illegal activities. There would be an outcry and widespread denunciation of such an assault on press freedom and the First Amendment. The latest revelations today, following Wikileaks’ publication of strategic sites considered vital to the US’s national security will increase the pressure to isolate and condemn Wikileaks and anyone who supports the site and Julian Assange. Not only have Amazon and PayPal now refused to do business with Wikileaks, but students at Columbia University have been warned that they risk their job prospects if they download the leaked diplomatic cables or even make comments about the documents on Facebook and Twitter. The advice was sent to students by Columbia’s Office of Career Services, following a tip off from an alumnus working in the State Department.

It is perhaps the fallout from Wikileaks’ mass publication of diplomatic cables, rather than the content of the cables themselves, that may do the most harm in the end. When one of the world’s leading liberal educational institutions advises self-censorship to its students, rather than encouraging them to explore and read one of the most significant publications of our time, it is clear that we are in the grip of such a damaging panic that it is threatening the core principles of freedom of speech. The fury over Wikileaks’ publication of the diplomatic cables is not only undermining the United States’ historic commitment to the First Amendment, but the Obama administration’s avowed support for internet freedom (spearheaded by Hillary Clinton) now looks decidedly hollow. It is the Swiss who currently emerge as the world’s champions of freedom of information, vowing to stand up to political pressure.

Wikileaks is here to stay. Wikileaks.org is still offline, but the content can now be accessed on more than 300 mirror sites. Even if the United States and its supporters such as France were successful in removing it for good, another version or a successor to Assange and his colleagues would take their place. Prosecuting Assange under the Espionage Act (one of the most draconian pieces of legislation in US history) will solve nothing beyond chilling the freedom not only of whistleblowers, but of everyone who wants to enjoy the right to share and exchange information freely. When Daniel Ellsberg faced trial for leaking the Pentagon Papers in 1973, it was press freedom and the public’s right to know that was in jeopardy. This time it’s the freedom of expression of us all. Whether you think Wikileaks’ behaviour is reckless or admirable, we all need to take the long view in considering the consequences.