Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

In South Africa, the singing of “struggle songs” remains a bone of contention. Some South Africans contend, along with the courts, that songs should be banned when their lyrics incite violence. Other South Africans regard the songs as a way to remember the anti-apartheid struggle.

On 31 October, South Africa’s ruling African National Congress (ANC), along with former ANC Youth League leader Julius Malema, reached an agreement with the white “minority rights” lobby group AfriForum and the Transvaal Agricultural Union (TAU) to avert the banning of the anti-apartheid struggle song Dubula iBhunu. “Dubula iBhunu” is a vernacular Zulu phrase that translates as “Shoot the Boer”.

AfriForum, along with TAU, and Malema and the ANC in its capacity as political party agreed that:

In the interest of promoting reconciliation and to avoid community friction, and recognising that the lyrics of certain songs are often inspired by circumstances of a particular historical period of struggle which in certain instances may no longer be applicable, the ANC and Malema commit to counselling and encouraging their respective leadership and supporters to act with restraint to avoid the experience of such hurt.

Their agreement has been made an order of the court. The ANC abandoned its appeal against the banning of the song while AfriForum agreed not to pursue the banning of the song. The parties committed themselves to further dialogue to deepen mutual understanding. In practice, ANC leaders will discourage their followers from singing songs deemed “hurtful” to “minority groups”.

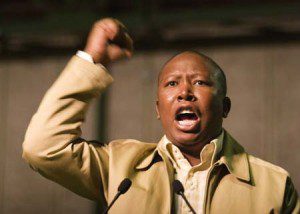

ANC Youth League leader Julius Malema “rediscovered” the anti-apartheid song in March 2010 in the process of bolstering his appeal to young black people who feel excluded from the material benefits of the country’s transition to democracy.

The South African Bill of Rights enshrines freedom of expression but explicitly excludes incitement of violence or advocacy of hatred to incite harm on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender or religion.

AfriForum obtained an order from the High Court last year banning Dubula iBhunu. The judgment found that the song referred to white Afrikaans people as rapists and robbers and dehumanised them by calling them “dogs”. “The process of dehumanisation is recognised … as one of the steps leading to genocide.” Malema was found guilty of hate speech.

The judgment included a reminder that South Africa’s jurisprudence regards

the right to dignity as “at least as worthy of protection as the right to freedom of expression… freedom of expression does not enjoy superior status in our law.”

The ANC appealed against the finding. It also lodged an appeal against another case involving the song: a member of the public, Willem Harmse, had taken another, Mohammed Vawda, to court in 2010 as the latter wanted to use “Dubula iBhunu” during a march against crime. Vawda argued that the song’s lyrics indicated “shooting apartheid” while Harmse, a white farmer, argued that the words could cause him personal harm. The high court had found the song to be an incitement to violence.

The appeal in the Harmse case was postponed in September this year in anticipation of the appeal in the case involving AfriForum, which would have come before the Supreme Court of Appeal this week.

The Mail and Guardian, a leading opinion-making newspaper, questioned the ANC’s decision to withdraw its appeal:

The settlement forestalls the testing of a questionable judgment with far-reaching implications. South Africans should be able to understand that what is legally permissible and what is wise or constructive are not the same. The law must leave wider parameters than political morality.

Nevertheless, South Africa has over the past few years witnessed the rise of a public discourse of intolerance that increasingly invokes violence, including Malema’s public declaration that he would “kill for Zuma” in the run-up to the 2009 election. Jacob Zuma subsequently became ANC leader and South Africa’s president. Rather than it being merely about legality or wisdom, the threat of violence has been used for specific political ends: to intimidate detractors and mobilise support.

In resurrecting Dubula iBhunu, Malema was following the example of Zuma, who had revived another “struggle song”, Awuleth’ Umshini Wami (“Bring My Machine Gun”). Zuma used the song as a war cry when his financial advisor faced a corruption trial in 2005, which implicated him, and when he (Zuma) faced rape charges in 2006.

Christi van der Westhuizen is Index on Censorship’s new South African correspondent

Court verdict comes as the populist politician Julius Malema faces internal disciplinary charges that could see him kicked out of the ANC. Louise Gray reports

(more…)

A South African court has today found Julius Malema, leader of the youth brigade of the country’s ruling African National Congress (ANC), guilty of hate speech. He was ordered to pay costs for singing an apartheid-era song that advocated the killing of white farmers. The civil case was brought against Malema by the Afrikaner civil rights group, Afriforum, who claimed white farmers felt vulnerable due to the song’s lyrics, which translate to “shoot the white farmer“.