Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The truth is in danger. Working with reporters and writers around the world, Index continually hears first-hand stories of the pressures of reporting, and of how journalists are too afraid to write or broadcast because of what might happen next.

In 2016 journalists are high-profile targets. They are no longer the gatekeepers to media coverage and the consequences have been terrible. Their security has been stripped away. Factions such as the Taliban and IS have found their own ways to push out their news, creating and publishing their own “stories” on blogs, YouTube and other social media. They no longer have to speak to journalists to tell their stories to a wider public. This has weakened journalists’ “value”, and the need to protect them. In this our 250th issue, we remember the threats writers faced when our magazine was set up in 1972 and hear from our reporters around the world who have some incredible and frightened stories to tell about pressures on them today.

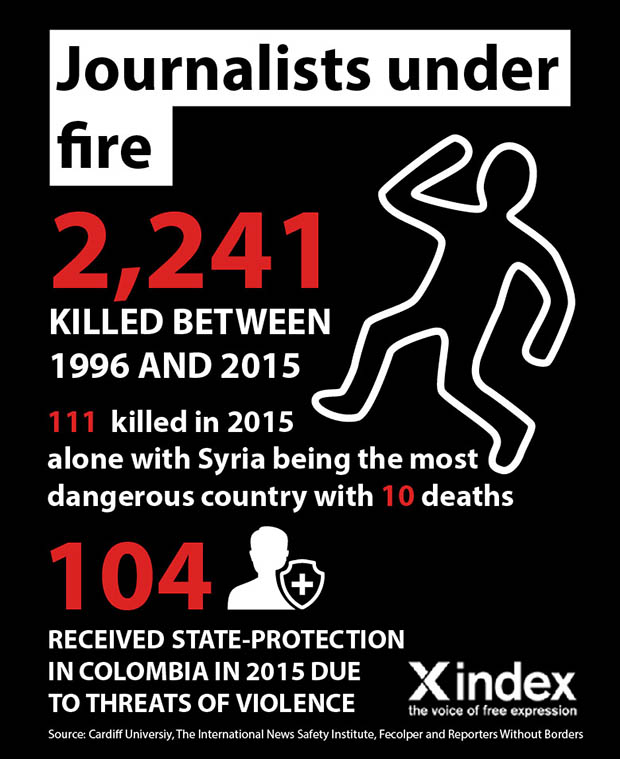

Around 2,241 journalists were killed between 1996 and 2015, according to statistics compiled by Cardiff University and the International News Safety Institute. And in Colombia during 2015 104 journalists were receiving state protection, after being threatened.

In Yemen, considered by the Committee to Protect Journalists to be one of the deadliest countries to report from, only the extremely brave dare to report. And that number is dwindling fast. Our contacts tell us that the pressure on local journalists not to do their job is incredible. Journalists are kidnapped and released at will. Reporters for independent media are monitored. Printed publications have closed down. And most recently 10 journalists were arrested by Houthi militias. In that environment what price the news? The price that many journalists pay is their lives or their freedom. And not just in Yemen.

Syria, Mexico, Colombia, Afghanistan and Iraq, all appear in the top 10 of league tables for danger to journalists. In just the last few weeks National Public Radio’s photojournalist David Gilkey and colleague Zabihullah Tamanna were killed in Afghanistan as they went about their work in collecting information, and researching stories to tell the public what is happening in that war-blasted nation. One of our writers for this issue was a foreign correspondent in Afghanistan in 1990s and remembers how different it was then. Reporters could walk down the street and meet with the Taliban without fearing for their lives. Those days have gone. Christina Lamb, from London’s Sunday Times, tells Index, that it can even be difficult to be seen in a public place now. She was recently asked to move on from a coffee shop because the owners were worried she was drawing attention to the premises just by being there.

Physical violence is not the only way the news is being suppressed. In Eritrea, journalists are being silenced by pressure from one of the most secretive governments in the world. Those that work for state media do so with the knowledge that if they take a step wrong, and write a story that the government doesn’t like, they could be arrested or tortured.

In many countries around the world, journalists have lost their status as observers and now come under direct attack. In the not-too-distant past journalists would be on frontlines, able to report on what was happening, without being directly targeted.

So despite what others have described as “the blizzard of news media” in the world, it is becoming frighteningly difficult to find out what is happening in places where those in power would rather you didn’t know. Governments and armed groups are becoming more sophisticated at manipulating public attitudes, using all the modern conveniences of a connected world. Governments not only try to control journalists, but sometimes do everything to discredit them.

As George Orwell said: “In times of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.” Telling the truth is now being viewed by the powerful as a form of protest and rebellion against their strength.

We are living in a historical moment where leaders and their followers see the freedom to report as something that should be smothered, and asphyxiated, held down until it dies.

What we have seen in Syria is a deliberate stifling of news, making conditions impossibly dangerous for international media to cover, making local news media fear for their lives if they cover stories that make some powerful people uncomfortable. The bravest of the brave carry on against all the odds. But the forces against them are ruthless.

As Simon Cottle, Richard Sambrook and Nick Mosdell write in their upcoming book, Reporting Dangerously: Journalist Killings, Intimidation and Security: “The killing of journalists is clearly not only to shock but also to intimidate. As such it has become an effective way for groups and even governments to reduce scrutiny and accountability, and establish the space to pursue non-democratic means.”

In Turkey we are seeing the systematic crushing of the press by a government which appears to hate anyone who says anything it disagrees with, or reports on issues that it would rather were ignored. Journalists are under pressure, and so is the truth.

As our Turkey contributing editor Kaya Genç reports on page 64, many of Turkey’s most respected news outlets are closing down or being forced out of business. Secrets are no longer being aired and criticism is out of fashion. But mobs attacking newspaper buildings is not. Genç also believes that society is shifting and the public is being persuaded that they must pick sides, and that somehow media that publish stories they disagree with should not have a future.

That is not a future we would wish upon the world.

Order your full-colour print copy of our journalism in danger magazine special here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Magazines are also on sale in bookshops, including at the BFI and MagCulture in London, Home in Manchester, Carlton Books in Glasgow and News from Nowhere in Liverpool as well as on Amazon and iTunes. MagCulture will ship anywhere in the world.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94291″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228208533353″][vc_custom_heading text=”Afghanistan in 1978-81″ font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228208533353|||”][vc_column_text]April 1982

Anthony Hyman looks at the changing fortunes of Afghan intellectuals over the past four or five years.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94251″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228208533410″][vc_custom_heading text=”Colombia: a new beginning?” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228208533410|||”][vc_column_text]August 1982

Gabriel García Márquez and others who faced brutal government repression following the 1982 election.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”93979″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228408533703″][vc_custom_heading text=”Repression in Iraq and Syria” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228408533703|||”][vc_column_text]April 1983

An anonymous report from Amnesty point to torture, special courts and hundreds of executions in Iraq and Syria. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Danger in truth: truth in danger” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F05%2Fdanger-in-truth-truth-in-danger%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The summer 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at why journalists around the world face increasing threats.

In the issue: articles by journalists Lindsey Hilsum and Jean-Paul Marthoz plus Stephen Grey. Special report on dangerous journalism, China’s most famous political cartoonist and the late Henning Mankell on colonialism in Africa.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”76282″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/05/danger-in-truth-truth-in-danger/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Watching the surreal videos of the police takeover of Turkish newspaper Zaman last week — inside the building police officers played cards behind the newspaper’s reception desk and devoured plates of baklava in the cafeteria as journalists looked on — I was reminded of the events of the past eight years that so definitively transformed Turkey’s media scene.

The change happened so gradually over the years that many missed the transformation. But journalism in Turkey has turned into a scene of feuds and long-held hostilities. The job description of a Turkish journalist now includes the ability to help lock up journalists from the opposite political camp.

Over the past eight years, a spate of legal cases have altered Turkey’s media environment beyond return. The most recent of these was the 2014 Selam Tevhid case, in which prosecutors intended to jail Turkey’s pro-government journalists who were accused of being foreign spies and aiding terrorist organisations.

But it was the OdaTV case of 2011 that had the greatest impact on journalism. The outcome silenced the popular and populist voice of secular nationalists and spread fear and paranoia to all media workers.

Earlier, in September 2008, after selling off his secular-nationalist broadcaster KanalTurk, Turkish journalist Tuncay Özkan was detained by Turkish police in relation to the Ergenekon investigation. He was detained in the Silivri Penitentiary, Europe’s largest penal facility where he would await the outcome of his trial for more than two years. One of Özkan‘s friends, Mustafa Balbay, the Ankara correspondent of Cumhuriyet newspaper, was also imprisoned in the same trial.

To many observers, Özkan’s and Balbay’s ideas were old fashioned, parochial and too nationalistic, views that somehow defined the way they were treated in the public sphere. There was little international reaction when Özkan’s KanalTurk‘s staunchly secularist and republican editorial line was changed overnight. The same broadcaster now defended polar opposite views.

After five years in detention, Özkan was sentenced in April 2013 to life imprisonment for being part of Ergenekon, a “ultra-secularist organisation that plotted a coup”. Balbay was luckier: he received 34 years and 8 months. Again, there was little world reaction to this surreal turn of events, but, in Turkey, many progressive voices applauded the verdicts, seeing them as part of what they ominously called the country’s “normalisation”.

Throughout 2008, Turkey’s media sphere changed enormously through these trials that made the criminalisation of Turkey’s media part of the journalistic occupation. More than a dozen journalists were detained in the OdaTV trials, accused of being members of the “media arm” of the terrorist organisation Ergenekon, named after Turks’ founding myth. There were so many arrests that the prison’s sports hall needed to be transformed into a courtroom to accommodate all the defendants.

Many of Turkey’s progressives bought into the idea that what was happening was a good thing. Once “ultra-secularist coup plotters” would be placed behind bars, Turkey would finally achieve its long-awaited “liberal consensus”. Those who opposed the arrests were branded reactionaries who should have known better.

According to the newspapers, Turkey was cleaning its bowels: there were lone dissenting voices but the general reaction to the prison verdicts was that all the bad, radical people were finally getting what they had long deserved.

The normalisation discourse was built on the idea that Turkey needed a “liberal consensus” where the extreme elements of politics and the media needed to leave the public sphere to moderates of all political persuasions. Thanks to this, Turkey would be able to become “a model democracy” in the Middle East.

As the trials continued, and more than 40 Kurdish journalists were imprisoned because of their alleged ties to terrorist groups, Turkey was represented as its most liberal self in the international scene — what made it democratic, the argument ran, was the trials themselves. In fact, Turkey was being its most illiberal self, having the highest number of journalists in prison at the time. In 2012, just a year before the anti-government Gezi Park protests, the country was being held up as a paradigm. A Reporters Without Borders report from that year, read: “With a total of 72 media personnel currently detained, of whom at least 42 journalists and four media assistants are being held in connection with their media work, Turkey is now the world’s biggest prison for journalists – a sad paradox for a country that portrays itself a regional democratic model.”

Worryingly, the Ergenekon and OdaTV trials moulded a new type of journalist who took pleasure in the jailing of his colleagues. After journalist and IPI World Press Freedom Hero Nedim Sener and his colleague Ahmet Sik were detained in 2011, they were conveniently added to the list of coup plotters. When journalist and editor Soner Yalcin was arrested in February 2011 along with other OdaTv journalists, this was seen as a blow to Turkish nationalism, rather than journalism. In the fight with nationalism, the locking up of nationalist journalists was seen as a necessary evil.

By 2011, the process that had begun in 2008 reached new heights, when the character assassination of journalists became commonplace in the Turkish press. It was now acceptable to publish transcripts of phone conversations between journalists who might have been plotting a coup.

A more troubling development was the rise of a new genre: more and more journalists devoted all their work to making incriminating accusations against their colleagues. The success of a journalist’s work was now defined by the outcome of trials he had supported with his columns: if he managed to get his colleagues convicted through defaming their character, he was promoted.

No political group was able to resist the attraction of this new, adrenaline-ridden form of journalism and, most alarmingly, readers who followed those developments, started taking joy in this spectacle, a development that would surely fascinate Michel Foucault. Journalism became meta: newspaper front pages tallied which journalists were locked up and which were freed. There was fresh material every other month: the political identities of imprisoned journalists changed but the end result was the same.

It is now clear how Turkey’s fake “liberal consensus” failed spectacularly. However unpalatable progressives found them, Turkey’s secularist-nationalists, socialists and communists defended their right to exist in a society where they constitute a historical phenomenon alongside Turkey’s conservatives. Their imprisonment in the name of normalisation was unacceptable and immoral.

Instead of a liberal consensus, what Turkey needs is a proper dissensus: the coexistence of these different political camps.

To tie in with the release of Index on Censorship magazine’s summer 2015 issue on academic freedom, Index put together a reading list of articles looking at the issues surrounding freedom of speech in universities from all over the world. Highlights include Kaya Genc’s examination of the Turkish universities that are restricting professors’ rights to teaching certain portions of history and Duncan Tucker’s look at the academics and students facing death threats in Mexico. There are also testimonies from young women who faced obstacles to getting an education.

All of these articles are taken from the special report of the summer 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Students and academics can browse the Index magazine archive in thousands of university libraries via Sage Journals.

Academic freedom articles

Kaya Genç, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 10-13

Index’s Turkish contributing editor discusses threats against professors that refuse to stick to the syllabus in Turkish universities

Universities under fire in Ukraine’s war by Tatyana Malyarenko

Tatyana Malyarenko, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 14-17

Academic’s jobs are under threat in Ukraine, Tatyana Malarenko discusses how many academics are being hauled in front of special committees and accused of terrorist activity

Industrious academics by Michael Foley

Michael Foley, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 18-19

Lecturer Michael Foley on the commercial pressures being applied to universities in Ireland

Stifling freedom: One hundred years of attacks on US academic freedom by Mark Frary

Mark Frary, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 20-25

Mark Frary takes us through one hundred years of attacks on freedom of expression in US universities

Martin Rowson, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 26-27

Cartoonist Martin Rowson’s regular Index illustration looks at students being gagged at graduation

Ideas under review by Suhrith Parthasarathy

Suhrith Parthasarathy, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 28-30

In India, the autonomy of universities is being challenged by Prime Minister Narendra Modi amidst growing concerns of censorship

Girls standing up for education by Natumanya Sarah, Ijeoma Idika-Chima, and Sajiha Batool

Natumanya Sarah, Ijeoma Idika-Chima, and Sajiha Batool, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 31-33

Three female students from Uganda, Nigeria and Pakistan discuss their experiences of their own education systems

Open-door policy? by Thomas Docherty

Thomas Docherty, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 34-39

Government suppression of UK universities is becoming more and more of an issue, reports Thomas Docherty. Includes the students view by the editor of The Cambridge Tab Sarah Ivers.

Mexican stand-off by Duncan Tucker

Duncan Tucker, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 40-43

Journalist Duncan Tucker lays out the battle for academic freedom in Mexico, where death threats, harassment and beatings are commonplace in universities

Return of the Red Guards by Jemimah Steinfeld

Jemimah Steinfeld, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 44-49

Index’s contributing editor in China Jemimah Steinfeld reports from China where a targeted campaign against anyone who criticises the ruling party has recently moved to universities

The reading list for threats to academic freedom can be found here

Another week, another social media ban in Turkey. I email a friend. to ask what are people making of this latest gross violation of free speech. “Nothing much,” comes the reply. “Lots of jokes though.”

Such is life these days in Erdoganistan, where every day brings a new censorship story, greeted now with what my Turkish friend calls “the humour of desperation”.

The latest ban on social media came, perhaps, with slightly more justification than previous attempts. Pictures of a state prosecutor, Mehmet Selim Kiraz, were circulated by the hard-left Revolutionary People’s Liberation Front (DHKP-C), which had taken him hostage. Hours after the pictures were released, Kiraz was dead. A court ordered that the picture of the dead man in perhaps his final moments be removed from certain sites, but the image proliferated. Hence the blocking of social media on Monday.

It was a case, as Kaya Genc wrote, of “burning the quilt to get rid of the flea”.

This is not unusual in Turkey. Last spring, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan vowed to put a stop to social media after leaked wiretap recordings circulated on Twitter. Back in 2007, the whole of YouTube was blocked because of a video that insulted Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey. That ban lasted three years, and even then-president Abdullah Gul raised his objections. During his presidency, in fact. Gul was never the most reliable friend of the authorities when it came to online censorship. Even during the 2014 ban, he tweeted “”The shutdown of an entire social platform is unacceptable. Besides, as I have said many times before, it is technically impossible to close down communication technologies like Twitter entirely. I hope this measure will not last long.”

In 2008, in one of my personal favourite incidents of online censorship, Richard Dawkins’ website was blocked because of a dispute with ridiculous, but powerful Turkish creationist Harun Yahya.

One has to admire Turks’ sanguinity in the face of such idiocy. It is not as if the web and social media are marginal in Turkish everyday life. As with any other country where half-decent smartphones are available, Turkish billboards and TV adverts are festooned with the familiar logos urging us to like, share, follow and the rest.

But Erdogan and the authorities appear convinced that the web is something that can be harnessed and controlled and without any detrimental effect.

Not that the Turkish president is alone in this belief. During the 2011 London riots, David Cameron famously suggested shutting down social media, to the delirious whooping of the likes of Iran’s Press TV and China’s Xinhua news agency: “Look,” they gleefully pointed out. “The British go on about free speech, and at the first sign of trouble, they want to shut down the internet.” It was rumoured that the Foreign Office had to intervene to point out how bad Cameron was making its diplomats’ human rights lectures look.

But there is a special kind of madness at play in Turkey’s multiple bans, a particular persistence. Ban it! Ban it again! Harder!

The Turkish state at times seems too much like a cranky uncle to be taken seriously, staring confusedly at the Face-book and worrying that somehow it’s a scam because they once heard about an email scam on the radio and now the computer is plotting against them.

But the problem is that Turkey isn’t your confused uncle. Turkey is a hugely important country. The attitude toward web censorship tells us a lot about Erdogan’s regime: it’s erratic, volatile, prone to paranoia, and increasingly suspicious of new things and the outside world. The president is prone to talking about his and Turkeys enemies, internal and external. The recent moves against the Gulen movement (including its newspaper Zaman) and refreshed hostility towards the PKK suggest Erdogan is up for a fight. Last month, he lumped the two movements together declaring that they were “engaged in a systematic campaign to attack Turkey’s resources and interests for years.” – sounding for all the world like Stanley Kubrick’s Brigadier General Jack D Ripper obsessing over plots to taint our precious bodily fluids.

Invoking the age-old Turkish paranoia of hidden power bases, Erdogan said: “We see that there are some groups who turn their backs on this people […] Two different structures that use similar resources have been attacking Turkey’s gains for the past 12 years. One uses arms while the other uses sneaky ways to infiltrate the state and exploit people’s emotions. Their aim is to stop Turkey from reaching its goals.”

Endless obsession over threats does not make for healthy government, let alone democracy. Some suggest that in his outspokeness and utter partiality, Erdogan is already overstepping the mark and creating a defacto US-style presidency – a stated aim.

Men with enemies lists are best avoided, and probably shouldn’t be allowed to be in charge of anything. Erdogan has all the appearance of being one of those men, and he’s been quite clear that the internet is on the list, saying after the 2013 Gezi protests that “Social media is the worst menace to society.”

This attitude is not a rational, but paranoia never is. For all that Turks can laugh at the president and the system, deep down they must worry.

This column was published on April 9, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org