24 Apr 2014 | Lebanon, News, Religion and Culture, Young Writers / Artists Programme

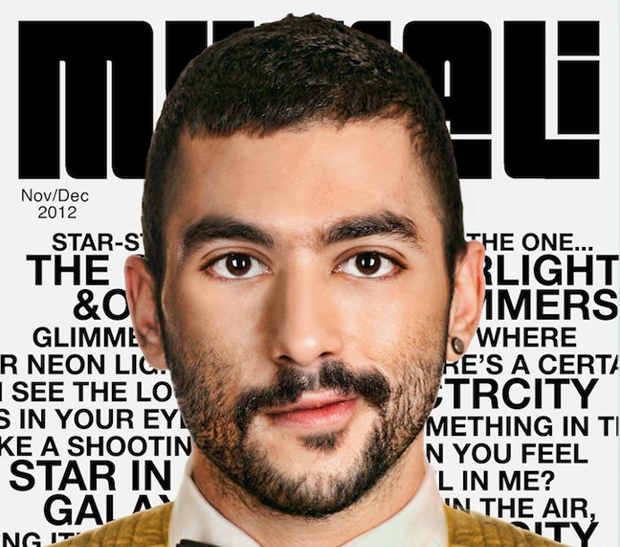

Hamed Sinno, who is openly gay, is the lead singer of Mashrou’ Leila

While walking the streets of the upscale downtown district of Beirut, or sipping cocktails in one of El-Hamra’s bustling bars, one could easily forget that Lebanon is a country where civil liberties are still in debate.

Article 534 of the Lebanese penal code states: “Any sexual intercourse contrary to the order of nature is punished by imprisonment for up to one year.” The vaguely worded article has and is still being used to crackdown on the LGBT community in Lebanon. Compared to its neighbours in the Middle East, Lebanon has long been considered one of the least conservative countries in the region. According to a poll conducted by the Pew Research Centre in 2013, 18% of the Lebanese population thinks that homosexuality should be accepted in the society, putting it way ahead of Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia where almost 97% of the population views homosexuality as deviant and unnatural.

The Lebanese Psychiatric Society issued a statement in early 2013 saying that: “The assumption that homosexuality is a result of disturbances in the family dynamic or unbalanced psychological development is based on wrong information” — making Lebanon the first Arab country to dismiss the belief that homosexuality is a mental disorder. On 28 January 2014, Judge Naji El Dahdah of Jdeideh Court in Beirut dismissed a claim against a transgender woman accused of having a same-sex relationship with a man, stating that a person’s gender should not simply be based on their personal status registry document, but also on their outward physical appearance and self-perception. The ruling relied on a 2009 landmark decision by Judge Mounir Suleimanfrom the Batroun Court that consenual relations can not be deemed unnatural. “Man is part of nature and is one of its elements, so it cannot be said that any one of his practices or any one of his behaviours goes against nature, even if it is criminal behaviour, because it is nature’s ruling,” stated Suleiman.

Despite the recent positives, being gay in Lebanon is still a taboo. In a country drenched in sectarianism, debates about homosexuality are easily dismissed in the name of religion and homosexuals are accused of promoting debauchery.

“People in Lebanon, and across the region, still act like homosexuality doesn’t exist in our society,” said Kareem, who requested that Index only use his first name. “I think it’s important that we start the conversation and get the issues out in the open, so people can start acknowledging it and then decide their stance on. The fight for our rights comes later on,” he added.

In 2013, Antoine Chakhtoura, mayor of the Beirut suburb of Dekwaneh, ordered security forces to raid and shut-down Ghost, a gay-friendly nightclub. “We fought battles and defended our land and honor, not to have people come here and engage in such practices in my municipality,” the mayor asserted.

Four people were arrested during the raid and brought back to municipal headquarters where they were subject to both physical and verbal harassment: forced to undress, enact intimate acts which included kissing, as well as being violently beaten. Marwan Cherbel, minister of interior at the time of the incident, backed the mayor’s actions, adding that: “Lebanon is opposed to homosexuality, and according to Lebanese law it is a criminal offence.”

Unfortunately, this was not an isolated incident. In a similar raid on a movie theatre in the municipality of Burj Hammoud known to cater for a gay clientele, 36 men were arrested and forced to undergo the now abolished anal probes — known as tests of shame. The raid came only a few months after Lebanese TV host Joe Maalouf dedicated an episode of his show Enta Horr (You’re Free) to exposing a porn cinema in Tripoli where it was claimed that young boys were being sexually abused by older men.

“The fact that these incidents received a lot of media coverage, some of which denounced the raids, is a sign that the public is little by little taking an interest in the issue of gay rights,” said Kareem. “Five or six years ago, this could have easily gone unnoticed. While the gay community might not be fully accepted or tolerated in Lebanon, it has been gaining a lot more visibility in recent years.”

Helem, a Beirut-based NGO, was established in 2004 to be the first organisation in the Middle East and Arab world to advocate for LGBT rights. In addition to campaigning for the repeal of Article 543, Helem offers a number of services, including legal and medical support to members of the LGBT community. Organisations like Helem and its offshoot Meem, a support group for lesbian women, had a huge impact on raising awareness and correcting misconceptions about homosexuality. Support from Lebanese public figures has also been on the rise in recent years. For example, popular TV host Paula Yacoubian and pop star Elissa have both shown support for the LGBT community in Lebanon via their Twitter accounts.

While the struggle to change the law continues, young artists have been challenging social norms through art. Mashrou’ Leila, a Beirut-based indie rock band, has sparked a lot of controversy thanks to their songs, in which they unapologetically sing about sex, politics, religion and homosexuality in Lebanon. In Shim el Yasmine, the band’s lead singer, Hamed Sinno, who is openly gay, sings about an old love, a man whom he wanted to introduce to his family and be his housewife. Director and art critic, Roy Dib, recently won the Teddy Award for best short film in 2014 at the 64th Berlinale International Film Festival with his film Mondial 2010. The film tells the story of a gay Lebanese couple on the road to a holiday weekend in Ramallah, Palestine. It tries to explore the boundaries that make it impossible for a Lebanese person to go into Palestine, as well as the challenges faced by a homosexual couple in the region.

The battle for gay rights in Lebanon is multilayered, and while change is starting to feel tangible, there is still a lot to be done.

This article was originally posted on 24 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

12 Feb 2014 | Lebanon, Volume 42.04 Winter 2013

Publicity photograph for Will it Pass or Not?

(Image: http://bourjeily.com)

When writer Lucien Bourjeily made censorship the theme of his latest play, he knew he was in for a battle. And he was right. His play about censorship ended up being banned. Not surprisingly, he thinks this decision tells its own story about Lebanon today.

“Because the censorship law in Lebanon is so vague and elusive,” he says, artwork that might have received approval two years ago are “censored or banned today”. “In this climate of fear,” he adds, “the military obviously becomes more present in day-to-day life, tightening security (through countless check points in almost every corner of Lebanon) and tightening their grip on freedom of expression. For the near future, I fear that we will be hearing about more bans, more censorship, and more constraints on freedom of speech in Lebanon: censorship thrives when the state feels insecure or when it makes the common mistake of correlating security and freedom of expression.”

On 28 August, he was summoned to the Lebanese Censorship Bureau and told that his play, Will It Pass or Not?, could not go ahead. The play, which tackles the theme of censorship head on, poses the difficult question that any Lebanese artist who explores controversial or sensitive issues must consider. Prior to Bourjeily’s encounter with the interior ministry, the play was performed on university campuses to invited audiences instead of theatres. Members of the censorship board attended and broke up the performance, even though a loophole in the law meant that the play could legally be performed in the venue. So Bourjeily decided to test the board and submitted the play for their consideration. On 3 September 2013, the censorship board’s General Mounir Akiki appeared on television, presenting evidence from four so-called “critics” who insisted the play had no artistic merit and therefore would not be passed. Often, the board will recommend changes that will make an artistic work more palatable – a line removed, the omission of controversial material. But in this case, the play was simply rejected. Index decided to publish an extract of the play so readers could make their own minds up.

In this extract from Will It Pass or Not?–published for the first time in English–Lucien Bourjeily exposes the ridiculousness – and arbitrary nature – of the Lebanese Censorship Bureau, which commonly bans material that is deemed to be obscene, offensive to religions or politically sensitive. Use of this translated script is copyrighted, please contact the magazine editor at Index about use of this material

Scene 2

Sergeant Da’ja, 35, is at his desk, looking through some papers. Kareem, 27, a director, is sitting on a chair next to the desk

Kareem raises his hand.

Sergeant Da’ja How long have you been waiting?

Kareem About an hour.

Sergeant Da’ja What have you got?

Kareem A screenplay.

Sergeant Da’ja Go on then, show me.

Kareem Please, here you are.

Kareem passes Da’ja the screenplay.

Sergeant Da’ja You’ve been here before, haven’t you?

Kareem Yes, I submitted a request, but it just got sent back. Someone from your office contacted me.

Sergeant Da’ja Okay. But I can’t do anything with it. Revisions are done by Captain Shadid.

Kareem Can I see Captain Shadid?

Sergeant Da’ja When the Captain is willing to see you. You’ll have to wait.

Kareem I’ll wait.

Captain Shadid, 40, enters the room. Da’ja stands to attention.

Sergeant Da’ja Good day to you, sir.

Flustered, Da’ja shuffles his papers. Kareem raises his hand again but Da’ja ignores him. Da’ja enters the Captain’s office, stamps his foot on the ground and gives a military salute.

Captain Shadid What have we got today, then?

Sergeant Da’ja The Sun newspaper, as usual, sir.

Da’ja hands the newspaper to the captain.

Captain Shadid Madame Noha again, I suppose…

Sergeant Da’ja As usual, sir.

Captain Shadid Have you even read it, you little shit? No, no, no…Just the same old rubbish. Goodness me … What am I to do with her?

Sergeant Da’ja You know best, sir.

Captain Shadid Okay, what else have we got today? Are there many waiting out there?

Sergeant Da’ja There’s someone outside who’d like to speak to you … about his film script. It’s the tedious one about sectarianism in Lebanon and the guys who go to India and set up a secular state … and all that nonsense.

Captain Shadid Yes, yes, I remember. Show him in …

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, sir.

Da’ja stamps his feet and salutes, then leaves the room. Captain Shadid makes a phone call.

Captain Shadid Hi, Noha. Where are you? Come in to my office, please. I’d like a word.

Da’ja goes back to writing on his papers. Kareem raises his hand again.

Sergeant Da’ja Again? You’re an inquisitive type, aren’t you? Always asking questions… Okay, you can go in now.

Kareem enters Captain Shadid’s office. Captain Shadid is on the phone. He gestures to Kareem to give him the screenplay and then sit down.

Sergeant Da’ja Hello, sir. Er, one thing, sir. About your son?

Captain Shadid Yes, what about him?

Sergeant Da’ja There’s a match at 4pm today. Barcelona–Madrid. Who’s going to take him?

Captain Shadid Isn’t there anyone here? Isn’t Sobhi here?

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, Sobhi’s here.

Captain Shadid Well, send Sobhi then.

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, sir. Right you are, sir.

Captain Shadid Mr Kareem.

Kareem Yes, captain?

Captain Shadid Is this your first film?

Kareem It’s the first one I’ve decided to film, yes. It’s taken me three years to write the script.

Captain Shadid Three years and this is what you’ve got to show for yourself?

Kareem It means a lot to me. What do you mean by “this”?

Captain Shadid Listen, there’s something I want to tell you. I’m saying this to you like a brother to a brother. So, this film of yours … I’m afraid it just isn’t up to scratch. The script was 120 pages. But we’ve had to do quite a lot of work on it and it’s got a bit shorter … But it’s turned out great. Let’s take the title, to start with … I mean, how dare you use a name like that? Fucked Up until Judgment Day? Did you really think that was acceptable? Really? Where did you get that idea?

And then there’s the swearing … We counted it all up: you’ve got “fuck you” four times and “you son of a bitch” 14 times. I mean, do you really think that’s reasonable?

Kareem It’s meant to show this guy’s personality: he talks a lot of crap. It’s “dramatic tension”… it’s meant to reflect real life. People do speak like that in real life, captain.

Captain Shadid Lots of people do all kinds of things but it doesn’t mean it gets our approval, my dear man. We really couldn’t condone this character … so we’ve cut him out altogether. Dramatic tension or not: there were quite a few other things we’ve had to cut out too … Like the first scene, for example. So these guys storm out of their sectarian community and stand up to the cleric. You show the priest getting up to mischief and the sheikh taking bribes.

And these guys who just run away, off to India … We can’t have it like this. We’ve got to think of our country’s image, too. So we’ve cut out that whole scene. But don’t worry – we’ll replace it with another scene with the same ending … The guys can leave the country, that’s fine … and go to India … but for tourism instead. So we’re just changing the mood a bit. The film’s much nicer this way. Better to have a film showing a nice, pleasant world rather than this ugly nightmare you had originally. Tourists are great, so the whole idea is much nicer than the stuff with the clerics and the corruption and the bribes … And at the same time, this will encourage tourism: after all, Lebanon is a superb touristic destination.

Kareem But now the film has lost its entire meaning!

Captain Shadid What do you mean it’s lost its meaning? It’s got even more meaning now! Listen, we’re a country of diversity, of coexistence … Your film was very inflammatory. It made the country look like a well of sectarian conflict, where clerics are stirring up trouble and exploiting the country’s problems for their own political motives … No, no, no – we can’t have that.

Kareem But, sir, how can we solve our country’s problems if we don’t talk about them?

Captain Shadid Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha … Ah, so you want to solve the country’s problems now, do you? With your film? Ah, that’s wonderful … Ha, ha, ha … Listen, I’ve got to uphold the law. There are certain parameters I have to work within. And the second scene, where they arrive in India and meet the Indian cleric … well, if he’s portrayed in a negative light, then – even if he’s Indian – it reflects negatively on Lebanese clerics, too. No, no, no – we can’t allow that. Why don’t we have him meeting someone else, instead – a salesman, perhaps? Something useful like that … The Lebanese are renowned for their business acumen, after all, and this would fit with the tourism angle. We’ve killed two birds with one stone … and made it all much simpler. This way, we can approve the text … As for the third scene [he looks down at the screenplay], well … I don’t really think the film needs to be 120 pages long. So, now we’ve got it down to 20 pages. It’s great… Better than nothing, anyway, so roll with it!

Kareem But, sir, now it’s just a short film!

Captain Shadid Yes, but why not? My niece made a lovely short film and it was a big hit at all the festivals round the world. What do you have against short films?

Kareem Sir, it’s just… [Gets a bit flustered] … It’s just I … I don’t understand how you’ve got it down to 20 pages!

Captain Shadid Khalas, come now – no need to get all hot and bothered. Honestly, I get hundreds of scripts on my desk every day and I assure you, your screenplay is much better this way. It’d make a lovely short film. God grant you success!

Kareem But, Captain Shadid, I’ve spent three years working on this script! Can’t we come to a compromise? Can’t we see if there are any smaller changes we could make instead?

Captain Shadid [answering the telephone] Hello? Yes, Brigadier-General. Certainly, sir. Yes, sir. I’m looking into the matter right now, sir.

Captain Shadid gestures to Kareem to see himself out of his office.

Kareem leaves the room and sits down on a chair in Sergeant Da’ja’s office. Da’ja enters. Kareem raises his hand again.

Sergeant Da’ja What, are you still here?

Scene 5

Noha enters Captain Shadid’s office.

Captain Shadid Hi.

Noha Are you angry?

Captain Shadid Me? Why would I be angry? My wife criticises my job day in day out… and today she’s gone as far as mentioning me by name! What did you have to go and put my name in for? Why?

Noha Darling, you’re the one who’s forbidden her from putting on the play.

Captain Shadid What do you mean forbidden?

Noha Well, what else am I supposed to say?

Captain Shadid Hmmm … So … What, have you been to see this play, then?

Noha Of course. But I doubt you have?

Captain Shadid She gets naked in it!

Noha What makes you say that? Have you even seen it?

Captain Shadid No, I’ve not been to see it… But I’ve heard plenty about it from the others. What difference does it make if I’ve seen it? It contains nudity! But, anyway, nudity or not… you shouldn’t be meddling in my work!

Noha I’m just doing the same with my work as you do with yours. As a journalist, I just express my opinion about things… and then you go and meddle in my work.

Captain Shadid My job is to enforce the law.

Noha Yes, and who wrote that law?

Captain Shadid Who wrote the law? Who? The law is in the name of the Lebanese people!

Noha What, so don’t you think the Lebanese people want to go to see this play? Because there’s never an empty seat in the theatre whenever I go.

Captain Shadid Listen, I’m just doing my job… What do you want me to do? I’m your husband… So? What do you want from me? You want me to abolish censorship? Shut down the entire directorate? Sit at home and twiddle my thumbs? Give 200 soldiers the boot?

Noha Yeah, yeah, very funny.

Captain Shadid Well, it’s just not acceptable. Every day, it’s the same old story with you. Isn’t there anything else in the country you could write about besides me?

Noha I’m not the first to write about politics and have you censor it! You’re always saying, “Give it up, girl. You’re just banging your head against a brick wall.” Well, what else should I write about? First, no politics… and now art is banned as well. What should I write about, then? I may as well throw in the towel and sit at home. Is that what you’d rather? You’re always trying to censor me just like those naked women that pile up on your desk.

Captain Shadid Well, we need censorship. What would life be like without any kind of oversight? It’d be carnage… Are we back in the dark ages living in a forest? Children need oversight, society needs oversight.

Noha You said it! Children need oversight – but we’re not children! I’m not a child and I want to see the plays I want to see…Man, living in a forest in the dark ages would be better than living with you.

Captain Shadid What do you want? Shall I get your editor to censor you or shall I pull the plug on your magazine? I mean it… Do you understand?

Noha Go ahead, then, censor it. Who’s going to rush out and buy it, anyway? You guys think it’s just “oversight”… but it’s not – it’s propaganda. And forbidding things just makes them more desirable.

Captain Shadid All right, enough. But just watch it, you. I can always divorce you!

Kareem is still waiting in Sergeant’s Da’ja’s office

Sergeant Da’ja So, your name’s Dalloum? Where are you from?

Kareem The Beqaa Valley.

Sergeant Da’ja Ah, Brigadier-General Dalloum is from Beqaa. Brigadier-General Damian Dalloum.

Kareem Damian Dalloum’s a great guy.

Sergeant Da’ja You know him?

Kareem He’s my father’s cousin.

Sergeant Da’ja Wallahi, no way! His cousin? His cousin? Gosh. Wait here a minute.

Da’ja enters the Captain’s office, stamps his foot on the ground and gives a military salute.

Sergeant Da’ja Er, excuse me, sir. The chap who’s just been in to see you this morning about the Indian film … from the Dalloum family.

Captain Shadid Yes, that’s all dealt with.

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, but he’s still here waiting … We’ve just been talking and it turns out that he’s a Dalloum Dalloum … He’s related to Brigadier-General Dalloum!

Captain Shadid Damian Dalloum?

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, sir…

Captain Shadid Well, why didn’t he say so?

Sergeant Da’ja I don’t know, sir, I don’t think he realised.

Captain Shadid What do you mean – he didn’t realise?

Sergeant Da’ja He didn’t realise that Brigadier-General Dalloum worked here in the directorate.

Captain Shadid How could he not know?

Sergeant Da’ja He might not have known. What would you like to do, sir?

Captain Shadid This film … we’ve had a look at it, right?

Sergeant Da’ja Yes … it’s a bit disrespectful in places, with some swearing … and the title’s rather strange …

Captain Shadid The film’s fine.

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, sir, there’s not really much to say about it.

Captain Shadid We could perhaps just change the title.

Sergeant Da’ja But it’s fine, otherwise.

Captain Shadid Yes, yes. What are you doing waiting out there? Show him in.

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, sir.

Da’ja steps back to his own office

Sergeant Da’ja The captain would like to see you.

Kareem stands up and enters Captain Shadid’s office

Captain Shadid Come in, Dalloum. Please, sit down. This is my wife, Noha. She writes for the Sun newspaper.

Kareem A pleasure to meet you. I always read your paper.

Captain Shadid Mr Kareem, your film is wonderful.

Kareem The short or the long version?

Captain Shadid No, the long version, of course! It’s a great film, wonderful!

Kareem But weren’t there a few things …?

Captain Shadid No, no. We’ve just gone back and had another look, and you were right: there’s not really anything to worry about. It’s very realistic, after all, and it’s got just the right amount of social and political criticism.

Kareem You mean, you’ll give me permission to film it?

Captain Shadid Yes, yes, of course. Don’t you fret! [To Noha] This film gets our full approval. You see: if it’s a great work of art, we approve it, and if it’s not, we don’t. It’s simple. Why do you always have to make such a mountain out of a molehill?

Captain Shadid God bless you, Mr Kareem. Go and see Sergeant Da’ja and he’ll sign it off.

Kareem Yes, captain. Thank you very much, sir!

Sergeant Da’ja Wallahi! So the captain has given you the go ahead?

Kareem steps back into Sergeant Da’ja’s office.

Kareem Yes, er …

Sergeant Da’ja He hasn’t changed the title?

Kareem No, it’s as it was.

Sergeant Da’ja It’s a wonderful film, very deep. It made a great impression on us all. I was the one who suggested that the captain had another look. So, I’ll just sign it off, and then you come back tomorrow for the permit – if it’s not too much trouble?

Kareem Not at all. It’s no trouble.

Sergeant Da’ja And Brigadier-General Dalloum will be here tomorrow too, so you can say hello. I’ll take you to see him. So, please, mind how you go. And what else have I forgotten? Ah yes, here’s my phone number, just in case.

Kareem Your number?

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, come to me direct, if there’s anything at all you need!

Use of this translated script is copyrighted, please contact the magazine editor at Index about use of this material

Translated by Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp

Director and filmmaker Lucien Bourjeily brought interactive, improvised theatre to Lebanese audiences, introducing the first improvisational theatre troupe, ImproBeirut, to the Middle East in 2008. His hard-hitting play 66 Minutes in Damascus, which draws on journalists’ and activists’ descriptions of Syrian detention centres, showcased at the London International Festival of Theatre in summer 2012, receiving critical acclaim. With Kiki Bokassa, he is the co-founder of the Visual and Performing Arts Association, which advocates the use of creative arts to help resolve social issues. Bourjeily is the winner of the 2009 British Council’s Young Creative Entrepreneur Award; he won the title of best director at the 2008 Beirut International Film Festival for his debut film Taht El Aaricha; and was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship in 2010, graduating with a Master in Fine Arts in Film from Loyola Marymount University (Los Angeles). He is also the author of Index on Censorship’s Tripwires manual.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2013 print edition of Index on Censorship magazine. It was posted to indexoncensorship.org on February 12, 2014

13 Sep 2013 | Lebanon, News, Religion and Culture

A publicity shot from Lucien Bourjeily’s latest play, Would It Pass Or Not?

Lucien Bourjeily retains a sense of humour. It’s an important attribute for a playwright taking on Lebanon’s censors.

Earlier this year, Bourjeily, an internationally acclaimed writer and director who dazzled the London International Festival of Theatre 2012 with his immersive work 66 Minutes In Damascus, wrote a play about Lebanese censorship. “Would It Pass Or Not?”, produced by anti-censorship group March, addresses the question every Lebanese writer and artists asks themselves before sitting down to begin a work.

Lebanon is a country battling to keep a lid on sectarian tensions, and eternally caught up in other people’s wars. Censorship is seen as a national security issue, and overseen by the army.

Like so many modern blue-pencillers, the Lebanese Censorship Bureau insist that it is only protecting citizens. There is, says Bourjeily, quite a bit of sympathy for this argument in the country.

So Bourjeily decided to tackle the topic head on and write not about the many sensitive issues in Lebanon but about the censors themselves.

Suspecting that the answer to “Would it pass or not?” would be an emphatic “not”, he and his company sought to exploit a loophole, performing their play on university campuses to invited audiences rather than in public theatres. The censors still pursued him. Two officers from the bureau turned up at a university show and broke up the performance. Bourjeily decided he would try to test the censor’s decision.

In conversation with Index, Bourjeily told of his bizarre encounters with the censor board’s general. He was summoned to the bureau in Beirut on 28 August.

The play cannot go ahead, he was told, because it was not realistic. It was exaggerated.

True, Bourjeily says. It’s fiction. Of course it’s unrealistic and exaggerated. Otherwise it would be a documentary.

The general turns to his subaltern and describes scenes from the play, asking “would such a thing happen here?”, unintentionally and ironically echoing a scene in the play itself. When censors are censoring a play about censorship, things are bound to turn to farce sooner or later.

Normally, Lebanon’s censors will suggest changes to works that will allow them to pass – a joke removed here, a political remark erased there. But with Bourjeily’s play, this was apparently not going to happen.

The censors’ next move was interesting: they would show, they said, that Boujeily’s play had no artistic merit. On 3 September, General Mounir Akiki appeared on television bearing testimony from four “critics”, each of whom said the same thing; that there was no artistic value in “Would it pass or not?”. Curiously, none of these critics were named, but their views were taken very seriously indeed. One said that Bourjeily’s play were “with a defamatory hallucination indicating the absence of his artistic level”, another that the play “was not related to the theatre, but rather with prosaic words and it does not meet the conditions regarding the structure.”

It’s a familiar ruse; if it’s not art, it’s not artistic censorship; if it’s rubbish, who would want to see it anyway?

In this, the censors echoed the notorious, and in hindsight ridiculous, court hearings over Lady Chatterley’s Lover in Britain in 1960 , the crux of the argument being whether the book was actually literature or mere obscene pornography. Great lengths were gone to by intellectuals such as Richard Hoggart to prove that Lady Chatterley’s Lover was literature, and thus, perhaps something one might wish your wife or your servants to read, at least if you were an enlightened sort of chap.

This is always what censorship of works of art comes down to: someone, be it the colonels, the Lord Chamberlain or whoever else, is to decide what you can read, what you can write, what ideas you can process. As the late Christopher Hitchens observed in a speech at the University of Toronto in 2006, if given the choice, would you nominate someone for that role? Or would you think you’d take your chances with your own intellect?

Lebanese writers and theatregoers are deprived of that option every day.

This article was originally published on 13 Sept 2013 at indexoncensorship.org