30 Jan 2014 | News, Religion and Culture

Fareed Zakaria (left) chaired two panels of LGBT activists at Davos. The first (above) consisted of Alice Nkom, Masha Gessen and Dane Lewis (Image: Twitter/@m_delamerced)

A panel of LGBT activists used the World Economic Forum last week to scrutinise recent homophobic laws passed by the Nigerian President, Goodluck Jonathan, despite rumours prior to the event suggesting it would be Putin who, for obvious reasons, would come under attack at the discussion.

Those taking part were flown into the event from around the world; Russian and American journalist Masha Gessen, Cameroonian lawyer Alice Nikom and J-FLAG Executive Director Dane Lewis were all present, as well as Human Rights Campaign President Chad Griffin, and Republican mega-donors Paul Singer and Dan Loeb.

Opening the breakfast discussion the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay said: “Two weeks ago President Jonathan of Nigeria signed into law a bill that criminalises, among other things, gay wedding celebrations, any public display of any same-sex affection, as well as the operating of gay clubs, businesses or organisations, including human rights organisations that focus on protecting the rights of LGBT people.”

Held rather ironically across the street from a discussion the Nigerian President himself was currently attending, Griffin followed suit: “Just to be clear what he signed, so everyone understands it in this room, it was already illegal to be LGBT but he further legalised it. You can be in prison for 14 years for simply being a gay person.

“Each one of you here would be subject to arrest because you’re in this room today: you’d go to prison for ten years. That’s what’s happening right now in that country and I bet you most people in that room don’t know what he’s just done.”

Putin’s name did manage to crop up in conversation and, not surprisingly, it was Gessen who had something to say.

She believes the Kremlin legitimately felt the LGBT community was the one minority it could beat up without fearing a backlash from the rest of the world- how wrong they were. The international reaction may have been slow to take off, she said, but the strong global response has come as a real shock to the Russian government.

“There is a reason why we talk about human rights and there is a reason why we talk about the protection of minorities, because minorities often do have to be protected from the majority, that’s the point,” Gessen said.

The ski resort of Davos, Switzerland welcomes around 2,500 of the world’s top business leaders, politicians, intellectuals and journalists each year to talk business. The singling out of countries or politicians for criticism during the conference is unheard of, according to Politico, which referred to the forum as a “week of political calm”.

This year’s conference came under the banner The Reshaping of the World: Consequences for Society, Politics and Business. Singer and Loeb, who organised the panel, reshaped the theme into a discussion about global sexuality and equality.

Loeb said: “We’re at the World Economic Forum. They say we’re here to make the world a better place. I think we need to take care of the injustices imposed on others in our efforts to make the world a better place.”

Griffin closed the talk by looking at the future of LGBT discussions at Davos, emphasising what an incredible start the first attempt at grabbing the world’s attention at the World Economic Forum was. But there were wishes that the intimate breakfast event would one day “be in the building across the street”.

Watch the full video of the discussion here.

This article was published on 30 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Dec 2013 | India, News

From a protest in Mumbai against Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code which, among other things, bans gay sex (Image: Abhishek Chinnappa/Demotix)

I woke up on 11 December to a phone call from my friend. She was in tears: “My parents would rather have me married than arrested. They are constantly saying that even the Supreme Court thinks my ‘lifestyle’ is illegal.” I wasn’t sure whether she was pulling a prank on me. It turns out she wasn’t. The date 11.12.13 had tossed at us a judgment that sent shockwaves through India’s LGBTQ population. The July 2009 ruling from the Dehli High Court, decriminalising sex between two consenting adult, including “gay sex”, had been overruled by the Supreme Court.

The Delhi High Court had ruled that Section 377 of the Penal Code was in violation of the Constitution — specifically Article 14 which guarantees “equality before law”, Article 15 which prohibits discrimination on the basis of “religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth” and Article 21 which protecting “life and personal liberty.” The Supreme Court, however, stated that the section can be repealed or amended only by the Indian Parliament.

“While reading down Section 377 IPC, the Division Bench of the High Court overlooked that a minuscule fraction of the country’s population constitute lesbians, gays, bisexuals or transgender people and in last more than 150 years less than 200 persons have been prosecuted (as per the reported orders) for committing offence under Section 377 IPC and this cannot be made sound basis for declaring that section ultra vires the provisions of Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution,” the Supreme Court stated. Is the implication that just because the LGBTQ community is a minority, it can do without basic human rights? If quantity is the yardstick, then surely we need not fight discrimination against the disabled, religious minorities or the tribals anymore?

After the Delhi High Court ruling, there was a general climate of optimism regarding the rights of sexual minorities. This is not to say that police harassment stopped or lesbians stopped committing suicide. Unlike in the past, this year’s the Chennai Pride march was not given permission to go along the beach, and had to change its route at the last minute. Parts of the route for the Hyderabad Pride parade was in areas with little traffic and hence had little visibility. Despite the official estimates, human rights groups like the People’s Union of Civil Liberties, Karnataka have extensively researched and published reports on how Section 377 has been widely used by the police and society at large to harass homosexuals, male sex workers and transgender people. Extortion, blackmail, rape, physical assaults have gone unreported in a climate of fear.

What if my family/neighbourhood/office comes to know of my orientation? Will I lose my job? Will my family disown me? Do I have affordable legal support at hand? These are some very basic questions that have played on the minds of hundreds of thousands within the LGBTQ community. Section 377 does not imply that one can simply be arrested for one’s sexual orientation; strict material evidence of specific sexual acts is necessary for arrest. But fear creates a vicious cycle of ignorance and more fear. Facts get subsumed and a threat becomes enough to buckle under. Combined with the country’s reactionary obscenity laws, this becomes a potent cocktail for further harassment.

Yet, organisations like Sappho for Equality have conducted regular workshops with the police and the medical establishment, and have found a largely receptive audience. Nine transgender people across the country came together to produce an album and television soaps featured queer tracks. Two of the four short films in “Bombay Talkies” — a compilation celebrating 100 years of Indian cinema, released earlier this year — dealt with the topics homosexuality and transgenderism. Commercials have targeted the modern, urban Indian LGBTQ population. So much so, that many researchers (including myself) started writing about elitism in the Queer movement. This is the backdrop against which the Supreme Court made its ruling! Where does this take us back to? Sappho’s members wonder whether they will be allowed space in governmental agencies anymore. Ranjita Sinha of ATHB (Association of Transgender/Hijra in Bengal) already reports how complaints of harassment are pouring in, citing the examples of Bijoy Maity, who was physically assaulted on the evening of the judgment by locals who did not want an “effeminate” neighbour.

The media has been largely supportive but this support has a flip side too. Each time they flash the ticker, “Homosexuality criminalised”, they end up perpetuating a climate of fear. Yet, Section 377 is not only about the rights of sexual minorities to be themselves and to choose how and whom they love. It also criminalises sex “against the order of nature” and hence even heterosexuals practising oral and anal sex — in other words non procreative sex — can fall within its ambit. The State is entering your bedroom and infringing your integrity and your bodily autonomy — it is dictating your sex life. Anybody, irrespective of sexual orientation, should be concerned by this judgment, a fact yet to be highlighted by the media. The largest democracy of the world is faced with a very basic question. Is it even a democracy if it cannot uphold the fundamental rights of its citizens? As we ponder this question, come on the streets and scream for our rights, my friend and many like her are faced with the uphill task of claiming and reclaiming their right to be themselves.

2 Dec 2013 | Croatia, News, Religion and Culture

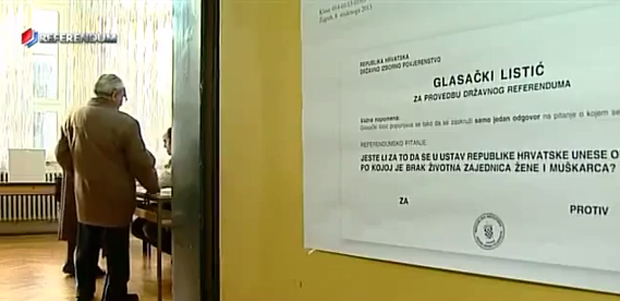

Croatians cast their votes on whether marriage should be constitutionally recognised as being between a man and a woman (Image: Mc Crnjo/YouTube)

Croatia’s voters moved Sunday to amend the country’s constitution to define marriage as being between a man and a woman. The campaign had been orchestrated by the country’s religious institutions. Sixty-five percent of voters supported a change that effectively bars gay marriage.

The campaign used some interesting and controversial tactics. Religious teachers in schools threatened students that they wouldn’t get a passing grade if they did not provide proof of their families’ support for the constitutional change. This was reported by an English language teacher from Split, the second largest city in Croatia, to the inspection body of the Ministry of Education around mid-November.

“If this is the situation in Split I believe it is even worse in smaller towns”, concluded the teacher who did not want to sign her name.

Following this, the media received numerous letters from school teachers confirming that religious teachers around Croatia were blackmailing students to make sure their family members vote “for the protection of the family” — the Catholic Church’s interpretation of the referendum question.

“If the president of the country and other public persons can talk about voting at the referendum why can’t a religious teacher do so?” commented Sabina Marunčić, senior advisor for religious education at the Croatian Education and Teacher Training Agency.

Since the call for a referendum on 8 November, the campaign has been the main topic of discussion in Croatia, despite the country facing a severe economic crisis and an unemployment rate of 20.3 per cent. While Croatian law defines marriage as a union between a man and a woman, this definition does not exist in the constitution. A recent announcement of a new law on same-sex partnerships has caused conservative movements to come together in the initiative “In the Name of Family”. They started spreading fear about gay marriage being legalised, despite the centre-left government showing no intention to do this. A 2003 law on same-sex partnerships has been seen as practically useless because it secures only a few, less important rights, and only after a relationship breaks down.

For weeks all anyone talked about was who will vote “for” and who will vote “against”, in the first national referendum in the Republic of Croatia set up by popular demand. The Social Democratic prime minister Zoran Milanović, President Ivo Josipović and numerous ministers all came forth against introducing the definition into the constitution. A large portion of powerful media was also openly against it. However, public opinion polls showed that 68 per cent of the citizens would vote for the proposal; 26 per cent against.

In the referendum campaign, the Catholic Church have firmly been advocating “for”. It has has a strong influence in the country of 4.29 million, with 86 per cent declaring themselves Catholic according to the latest census, released in 2011. The initiative “In the name of family” which has succeeded in gathering signatures of 740,000 citizens in order to hold a referendum is also linked to the Catholic Church.

“The church did not want to start the initiative for a referendum but it wholeheartedly accepted In the Name of Family, whose numerous members are conservative Catholics close to certain Croatian bishops,” says Hrvoje Crikvenec, editor of the religious portal Križ života (“Cross of Life”).

“However, I believe that the entire organisation and initiative is supported more by politics, that is, a marginal political right-wing party Hrast, than Croatian bishops. They have now become more involved in the campaign in the hope of what would for them be a positive outcome of the referendum, which would ultimately show them as winners.”

The initiative’s leaders do come from the non-parliamentary right-wing party Hrast, as well as conservative associations opposing the introduction of sex education in schools, artificial insemination and abortion. Some of them have been linked to Opus Dei, a secretive Catholic organisation which has been strengthening its presence in Croatia. In the Name of Family and the fight against a possible equal standing of homosexual and heterosexual marriages has provided them with the support of a larger portion of the public.

The Catholic Church has undoubtedly helped the success of a In the Name of Family. Signatures were gathered in front of churches and elsewhere, even in universities. Cardinal Josip Bozanić had written a note instructing priests to encourage believers in masses to attend the referendum and vote for the definition of marriage as a union between a man and a woman. Group prayers for its success were also organised throughout Croatia in the lead up to the vote.

“We can’t blame the bishops for advocating the referendum from the altar because this is a part of the church’s program. They are more entitled do so than to say who to vote for at the elections, which they also do. However, it is inadmissible for religious teachers to influence children in schools,” university professor of philosophy and political commentator Žarko Puhovski says.

Despite Croatia being a majority Catholic country, every fourth marriage ends in divorce and a decreasing number of couples are deciding to marry.

“The church’s influence on citizens is far greater regarding political than moral views. Church morality is accepted in principle, but political views supported by the church gain additional power. That is why the referendum is causing a short-term increase in the influence of the church, which has for years been weakening,” Puhovski explains.

Church leaders are often complaining about the non-existent dialogue with the current, left-wing government, especially regarding the issues they consider to be related to religion – education of children, family care and marriage.

“The ultimate success of this referendum is in showing the power of the church in Croatia. It has shown the government that it can move masses of people so in the future, the government will have to think carefully before making any decision which could harm their interests,” said a group of Roman Catholic theologists in a joint letter made public on 29 November.

“The relationship between the church and the state has mostly been disturbed by militant statements of individuals from the Catholic Church leadership, which seem to be best served with a one common mindset rather than political and worldview pluralism,” sociologist and ex-ambassador for the Holy See, Ivica Maštruko says.

“We are not dealing with a normal criticism of the current social state and relations, but bigotry, inappropriate discourse and civilisational and religious malice,” Maštruko added.

An example of such a discourse is provided by reputable former minister and theologist Adalbert Rebić who, earlier this year, was quoted as saying: “The conspiracy of faggots, communists and dykes will ruin Croatia.” Pastor Franjo Jurčević was convicted for publishing homophobic and extremist posts on his blog.

But in the campaign for the referendum the Catholic Church was joined by representatives of the other most influential religious communities in Croatia – Orthodox Christians, Muslims, Baptists and the Jewish community Bet Israel. Together they supported the referendum and invited the believers to vote in order to “secure a constitutional protection of marriage”. Religious communities in Croatia are usually rarely seen forming such shared views.

“The most interesting thing is the agreement between the Catholic Church and the Serbian Orthodox Church which have in the past twenty years completely missed the chance to initiate reconciliation, dialogue and co-existence during and after the wars in ex-Yugoslavia. Religious communities in the region can obviously agree only when they find a common enemy, which in the case of this referendum are LGBT persons,” Cirkvenec says.

Žarko Puhovski considers it indicative that religious communities in Croatia succeed in forming shared views only with regards to sexual morality.

“They have failed to reach a consensus on any other moral or political issue,” he concludes.

This article was published on 2 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

29 Nov 2013 | News, Uganda

Hundreds of Ugandans took to the streets in support of the government’s proposed anti-homosexuality bill in 2009 (Image: Edward Echwalu/Demotix)

The Ugandan government’s position on homosexuality is considered one of the harshest in the world. The proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill, seeks to, among other things, broaden the criminalisation of homosexuality so that Ugandans who engage in same-sex relations abroad can be extradited to Uganda and charged. Originally, some of the provisions in the law called for death penalties or life sentences for those convicted as homosexuals. It has since been amended to remove the proposal of death penalties, but the life sentences remain.

A special motion to introduce the legislation was passed only a month after a two-day conference where three American Christians asserted that homosexuality is a direct threat to the cohesion of African families. Indeed, the church — both Anglican and Catholic — plays a big role in shaping the government’s tough stance on homosexuality. New Pentecostal churches are also fuelling the anti-gay message, with firebrand crusaders like Pastor Martin Sempa at the forefront.

Together, the state and the church accuse the gay community of recruiting young people in schools. There have also been claims that gay people are recording sex videos with young Ugandans that they then sell abroad. It is said that young people are lured into this with promises of financial gains. Sixty-five-year-old Brit Bernard Randall is facing trial for engaging in gay sex, and for possession of videos of him engaging in gay sex.

Anti-gay legislation has been in place in Uganda for some time. Laws prohibiting same-sex sexual acts were first introduced under British colonial rule in the 19th century, and those were enshrined in the Penal Code Act 1950. Section 146 states that “any person who attempts to commit any of the offences specified in section 145 commits a felony and is liable to imprisonment for seven years.” On 29th September 2005, President Museveni also signed a constitutional amendment prohibiting same-sex marriages.

But the anti-gay bill is not the only story on this topic to come out of Uganda in recent times. In 2004, the Uganda Broadcasting Council fined Radio Simba $1,000 for hosting homosexuals on one of its shows, and the radio station was forced to make a public apology. In January 2011, LGBT activist David Kato was killed. Kato, together with Patience Onziema and Kasha Jacqueline, had successfully sued a Ugandan paper the Rolling Stone and its Managing Editor Giles Muhame. The paper had published their full names and photos, as well as those of a number of other allegedly gay people and called for the lynching of all homosexuals. The court issued a permanent injunction preventing the paper and the editor from publishing the identities of any other homosexuals. Kato’s murderer, Enoch Nsubuga, was handed down a 30-year prison sentence.

On 3 October 2011, a local human rights and LGBT activist challenged a part of the Equal Opportunities Commission Act in the Constitutional Court. Section 15(6)(d) prevents the Equal Opportunities Commission from investigating “any matter involving behaviour which is considered to be (i) immoral and socially harmful, or (ii) unacceptable by the majority of the cultural and social communities in Uganda.” The petitioner argued that this clause is discriminatory and violates the constitutional rights of minority populations. A decision has not yet been made on the petition.

The bill has, however, caused the most outrage. The Ugandan government and the evangelicals faced immense international criticism, and the bill was met with protests from LGBT, human rights and civil society groups. Countries including Sweden even threatened to stop their aid to Uganda in protest.

In response to the attention, the bill was revised to drop the death penalty, and President Yoweri Museveni formed a commission to investigate the possible repercussions of passing it. The Speaker of the Ugandan parliament promised in November 2012 the bill would pass by the end of the year as a Christmas gift for the group that supported it. It is, for now, still on hold. But while the Ugandan government has toned down its rhetoric against the gay community lately — this is believed to be due to international pressure — the persecution of gay people in the country persists.

This article was originally posted on 29 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org