23 Apr 2015 | Africa, Angola, mobile, News and features

Journalist and human rights activist Rafael Marques de Morais (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

The trial of Rafael Marques de Morais, the investigative journalists who has exposed corruption and serious human rights violations connected to the diamond trade in his native Angola, will restart on 14 May. He was initially set to appear in court again on 23 April, but was informed of the postponement late in the evening on 22 April.

Marques de Morais is being sued for libel by a group of generals in connection to his work. The parties will be negotiating ahead of 14 May, to try and find some “common ground”, Marques de Morais told Index.

“In the interest of all parties and for the benefit of continuing work on human rights and for the future of the country, it is a very important step to be in direct contact,” he said.

“Rafael’s crucial investigations into human rights abuses in Angola should not be impeded by this dialogue. Index stresses the importance of avoiding any form of coercion,” said Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

Marques de Morais originally faced nine charges of defamation, but on his first court appearance on 23 March was handed down an additional 15 charges. The proceedings were marked by heavy police presence, and five people were arrested. This came just days after he was named joint winner of the 2015 Index Award for journalism.

The case is directly linked to Marques de Morais’ 2011 book Blood Diamonds: Torture and Corruption in Angola. In it, he recounted 500 cases of torture and 100 murders of villagers living near diamond mines, carried out by private security companies and military officials. He filed charges of crimes against humanity against seven generals, holding them morally responsible for atrocities committed. After his case was dropped by the prosecutions, the generals retaliated with a series of libel lawsuits in Angola and Portugal.

“Despite major differences, there is a willingness to talk that is far more important than sticking to individual positions. But this cannot impede work on human rights, freedom of the press and freedom of expression,” Marques de Morais added.

This article was posted on 23 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Jul 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, Ireland, News and features

(Image: Quka/Shutterstock)

A recent court ruling in Ireland could have reintroduced the concept of criminal libel to the state, despite criminal defamation offences being abolished as recently as 2009.

The case itself was one of a particularly grim relationship break up. Names are not available as the people involved were also locked in a criminal case in which the male partner was accused of rape and false imprisonment, though he was acquitted of both.

But the details available are: couple breaks up in January 2011. They remain in touch. In April 2011, man goes to woman’s house to, according to the Irish Times’s report “confront her over a perceived infidelity”. Man later leaves woman’s house, but not before stealing her phone. Man goes through woman’s messages, which suggest she has started a new relationship. Man opens woman’s Facebook on phone and posts remarks from her account, making it appear that she is presenting herself as a “whore” who would take “any offers”. Drink was a factor, as the Irish court reporting phrase goes.

This action led to a charge under the Criminal Damage Act 1991, under which “A person who without lawful excuse damages any property belonging to another intending to damage any such property or being reckless as to whether any such property” can find themselves liable to a large fine and up to 10 years in prison.

In this case, the defendant was found guilty and fined €2,000.

The judge, Mr Justice Garrett Sheehan, is reported to have asked how to assess the “damage” when nothing had actually been broken. Prosecutors replied that the case was in fact more akin to harassment and that the “damage” had been “reputational rather than monetary”.

The first question here is obvious: if the facts of the case were more akin to harassment, then why were charges not brought under Section 10 of Ireland’s Non-Fatal Offences Against The Person Act, which would cover anyone who “by his or her acts intentionally or recklessly, seriously interferes with the other’s peace and privacy or causes alarm, distress or harm to the other”? Wouldn’t this be the obvious piece of legislation to use?

But after that, there are a few more: Who actually owns a Facebook profile? And does reputation count as property? And crucially, has Mr Justice Sheehan created a criminal libel law?

Ireland has a complicated relationship with social media. On the one hand, to be plain about it, the big online companies create a lot of employment in Ireland. Facebook, Twitter and Google all employ a lot of people in the country. On the other hand, it is susceptible to the same moral panics as anywhere else, and in a small, largely homogenous country, panics can be enormously amplified.

When government minister Shane McEntee committed suicide in Christmas 2012, the tragic story somehow became conflated with social media and online bullying. McEntee’s brother blamed the minister’s death on “people downright abusing him on the social networks and no names attached and they can say whatever they like because there’s no face and no name”. But his daughter later refuted that claim, saying: “Dad didn’t use Twitter and wasn’t a huge fan of Facebook. So I don’t think you can blame that and I’m not going to start a campaign on that.”

The subsequent debate on social media bullying was almost tragic in its simplicity, the undisputed highlight being Senator Fidelma Healy-Eames describing to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Transport and Communications how young people are “literally raped on Facebook”.

As ever in discussions that involve social media, a generation gap opens up, or is invoked, between younger “natives” who supposedly instinctively understand the web, and a political and judicial class who are apparently hopelessly out of touch. There is certainly an element of truth to this (I have sat in courts and watched judges express utter bafflement at the very concept of Twitter), but in general, what is actually happening is legislators, magistrates and the judiciary are desperately trying to apply existing, supposedly universal laws to phenomena to which they are simply not suited. This is where controversy usually arises, for example in the UK’s use of public order laws when the only threat to public order is a Twitter mob — as in the case of jailed student Liam Stacey; or use of laws against menacing communications in instances where it’s clear no menace was intended — such as Britain’s now infamous Twitter Joke Trial.

In the current Irish case, it seems obvious that harassment would have been the more relevant charge, but in this instance, that’s not what we have to worry about. The real concern is that by apparently putting reputation in the category of property which can suffer damage, the court has now created a precedent where damage to a person’s reputation, whether by “fraping”, tweeting, or even just the getting facts wrong in a news story, could lead to criminal sanction.

And the very worst thing is that no one seems to have noticed.

From the introduction of the new blasphemy law onward, Ireland has seen a slow, stealthy erosion of free speech. It’s not clear what will get people to start paying attention, but the country needs to be more vigilant.

This article was posted on July 10, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

21 Feb 2014 | Index Reports, Media Freedom, News and features, United Kingdom

Britain has always had a complicated relationship with the free press. On the one hand, Milton’s Apologia, Mill’s On Liberty, Orwell’s volleys at censorship and propaganda.

On the other hand, there is a sense that journalists, editors and proprietors are at best incompetent and at worst genuinely venal people whose sole interest is making others miserable.

This ambivalence carries over into the political debate about the media, and the laws and regulations governing the press and broader free speech issues. All British politicians pay lip service to free speech, but the records of successive governments have been far from perfect. For every success, there is a setback.

This paper will provide a brief overview of the state of media freedom in the UK today

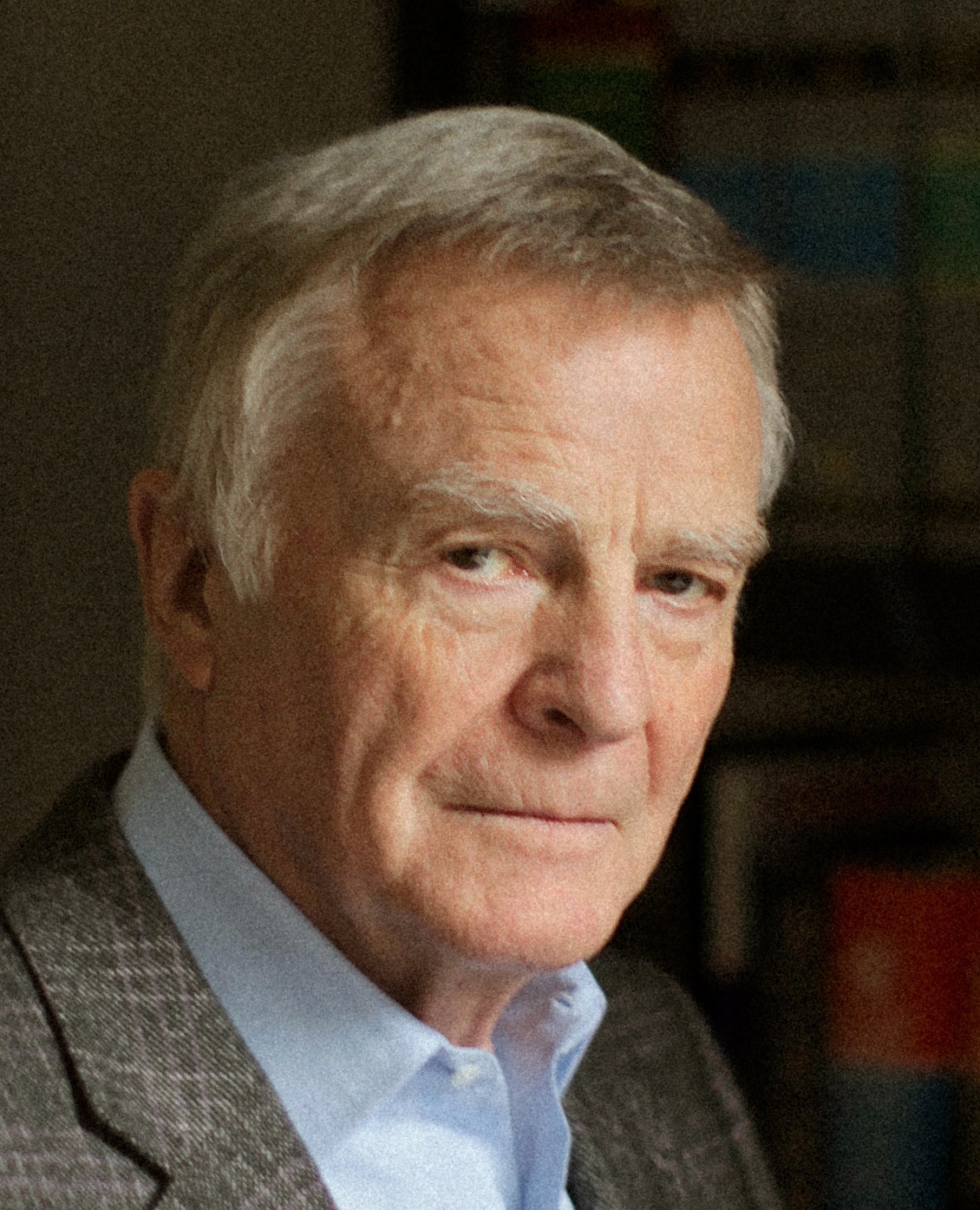

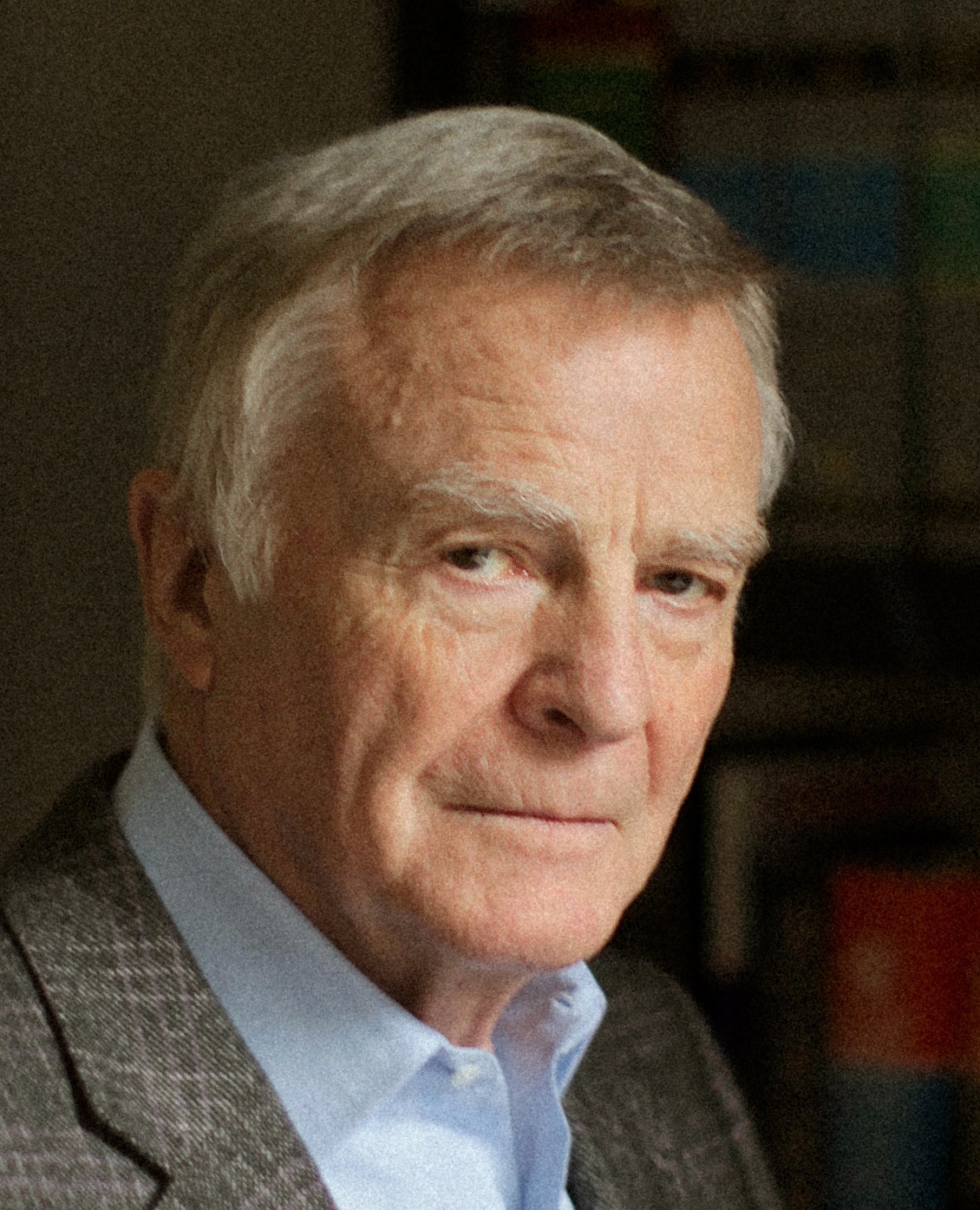

Press regulation and the Royal Charter

The Leveson Inquiry into the press reported in November 2012, with numerous recommendations on how press regulation should proceed. After months of negotiation led to deadlock over the issue of a “statutory backstop” to a regulator, in April 2013 the government attempted to resolve the issue, publishing a draft of a “Royal Charter” for the regulation of the press. In spite of the newspapers’ attempt to put forward their own competing royal charter, the Privy Council officially approved the government version in October 2013.

While the government and supporters claim that this is insulated from political interference, requiring consent of all three main parties in both houses (as well as a 2/3 majority) before the charter can be altered, critics say that royal charters, granted by the Privy Council, are essentially still political tools.

But how did we get to this point?

The Leveson Inquiry was called in response to the phone hacking scandal which gripped the country in 2010 and 2011. Journalists and contractors for News of the World, News International’s hugely successful Sunday tabloid, were alleged to have hacked the voice message of 100s of people, most notoriously murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler. Several criminal trials of senior News International figures continue at time of publication.

As allegations of dubious behaviour began to be made against other papers, judge Sir Brian Leveson was charged with leading an inquiry into the industry. The inquiry, which opened in late 2011, heard from a huge range of people, from celebrities to civil society activists.

An increasingly polarized debate has seen the newspapers lined up on one side, opposed to the current Royal Charter, and campaign group Hacked Off, as well as the major political parties, on the other. The newspapers plan to set up their own regulator, the Independent Press Standards Organisation, which may not seek recognition under the Royal Charter. It is claimed that IPSO will be operational by 1 May. This would be funded by the newspapers, with representation from the industry on its governing bodies.

Hacked Off and their supporters, who claim to represent the interests of victims of phone hacking and press intrusion, say that the newspapers cannot “mark their own homework”, and insist that any regulator must be “Leveson compliant” and recognised under the Royal Charter.

There have been confusing political signals. While Culture Secretary Maria Miller suggested that IPSO, if it functioned well, may not need to apply for recognition, the Prime Minister David Cameron told the Spectator magazine that he believed that the Royal Charter was the best deal the press would get, and that publishers should sign up lest a more authoritarian scheme be introduced.

Index on Censorship has opposed the Royal Charter and supporting legislation on several grounds.

– Changing the Royal Charter While supporters claim the Royal Charter cannot, practically, be changed by politicians, Index believes it would be possible to gain the two-thirds majority required in both houses to alter it, particularly if there were to be another hacking-style scandal. The Privy Council is essentially a political body, and recognition by royal charter a political tool.

– Exemplary damages The Crime and Courts Act sets out that an organisation which does not join the regulator but falls under its remit will potentially become subject to exemplary damages should they end up in court. In addition, even if they win, they could also be forced to pay the costs of their opponents. While it is claimed that membership of a regulator with statutory underpinning is voluntary, it is clear that there are severe, punitive consequences for those who remain outside the regulator. There is controversy over whether this is compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights.

The imposition of exemplary damages is likely to have a strongly chilling effect on freedom of expression – this could be particularly felt by already financially squeezed local publications and small magazines.

– Corrections The Royal Charter proposes the regulator will be able to “direct” the wording and placement of apologies and corrections. This is an effective transfer of editorial control. It represents a level of external interference with editorial procedures that would undermine editorial independence and undermine press freedom. A tougher new independent regulator could reasonably require corrections to be made, but directing content of newspapers is a dangerous idea.

– Scope The Royal Charter is designed, in its own words, to regulate “relevant” publishers of “news-related material”. It sets out a very broad definition of news publishers and of what news is (including in the definition celebrity gossip). Despite some subsequent attempts by politicians to establish some exclusions, such as for trade publications and charities for instance, the attempt to distinguish press from other organisations remains problematic. In a media industry undergoing rapid change, distinctions between platforms are increasingly blurred, and stories from unlikely sources can have every bit as much impact as those from the traditional media whose power pro-regulation activists seek to curb.

The next few months will be crucial as IPSO and alternatives, such as the IMPRESS project, take up positions. IPSO will be keen to recruit publications that have not already joined and present itself as fait accompli, pointing out that nowhere in the Leveson recommendations is there specific mention of a Royal Charter.

But at the core of the entire argument is the fundamental fact that the government has been willing to use coercive, punitive measures specifically directed at the press.

Libel – a free speech victory?

On 1 January, the Defamation Act 2014 became statute. The new law, represented a victory for the Libel Reform Campaign led by Index on Censorship, English PEN and Sense About Science. The LRC had its roots in two things – English Pen and Index on Censorship’s report “Free Speech Is Not For Sale” and Sense About Science’s campaign “Keep Libel Laws Out Of Science”.

That campaign identified key problems with England’s libel law, which was simply not fit for the internet age. Among the issues were the ease with which foreign claimants could bring cases in London courts, and the lack of a coherent statute of limitation on web publication.

The new act, while still far from perfect, is, at least on paper, an improvement on what has gone before. It should in theory provide greater protection for writers.

Among the changes are the introduction of a strong public interest defence, a one-year statute of limitation on online articles (where previously each new “download” counted as a new publication), and a “serious harm” test for corporations wishing to sue for defamation.

One major point of concern is the refusal of Northern Ireland’s government to update its statute books in line with that of England and Wales. Libel lawyer Paul Tweed, who practices in Belfast, Dublin and London, has pointed out that wealthy litigants hoping for a more claimant-friendly regime may now take cases to Belfast rather than London. It is imperative that pressure continues to be put on the political parties in Northern Ireland to introduce the new legislation.

Surveillance and protection of sources

There is little doubt about what was the biggest global story in 2013. The revelations about global surveillance carried out by the US’s National Security Agency, with the help of Britain’s GCHQ, dominated much of the global conversation. But while the US has made some noises about reviewing its surveillance procedures (though it has shown no intention of halting its pursuit of whistleblower Edward Snowden), the UK government managed a very special combination of burying its head in the sand and shooting the messenger.

The Prime Minister warned the Guardian that it should stop publishing revelations or face legal action. Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger was summoned before parliament and accused of deliberately endangering British security.

Security officials even visited the Guardian and demanded that hard drives containing leaked material be destroyed in front of them, in spite of the fact they were aware the data was also held elsewhere.

David Miranda, the partner of the Rio-based journalist Glenn Greenwald, was stopped at Heathrow airport under terror legislation. This was clearly done in order to confiscate source material.

That action was challenged in the courts by Miranda, with Index on Censorship entering evidence in support of the case. The legal challenge to the detention of Mr Miranda has been dismissed by the High Court, though there is the possibility of an appeal.

The case raises serious questions about protection of journalists’ materials and sources. There was also grave concern that terror legislation was used against a person carrying out journalistic activity.

Meanwhile, the government has proposed, as part of the deregulation bill, a new system which would make it easier for authorities to force journalists to hand over materials and information about sources. The Deregulation Bill could, if passed unamended, strip away safeguards for journalists faced with demands for their materials from police, removing the requirement for judicial scrutiny of such demands.

Conclusion

2014 will be a crucial year, not just for newspapers, but for free speech for everyone in the UK. For as the wall between publisher and consumer is rapidly being dismantled, it will become harder and harder to compartmentalise press freedom and general principles of free speech.

While the reform of our libel laws will, we hope, be of great benefit to to free expression in the UK and beyond, there are still several areas where this government can act to safeguard the free press and free speech more broadly in the coming year. Chief among these is that we must allow press self-regulation to proceed without coercion. No one should be forced to sign up to the press Royal Charter, and no one should be subjected to exemplary damages. In short, self-regulation should be just that.

Moreover, the government should state its commitment to protection of journalistic sources, a crucial cornerstone of the fourth estate which has come under severe threat as a result of the Miranda case.

Finally, the government should ensure that Belfast does not become a haven for libel tourism, by doing everything it can to support the extension of the new Defamation Act to Northern Ireland.

2 Jan 2014 | European Union, News and features, Politics and Society

The law of libel, privacy and national “insult” laws vary across the European Union. In a number of member states, criminal sanctions are still in place and public interest defences are inadequate, curtailing freedom of expression.

The European Union has limited competencies in this area, except in the field of data protection, where it is devising new regulations. Due to the impact on freedom of expression and the functioning of the internal market, the European Commisssion High Level Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism recommended that libel laws be harmonised across the European Union. It remains the case that the European Court of Human Rights is instrumental in defending freedom of expression where the laws of member states fail to do so. Far too often, archaic national laws have been left unreformed and therefore contain provisions that have the potential to chill freedom of expression.

Nearly all EU member states still have not repealed criminal sanctions for defamation – with only Croatia,[1] Cyprus, Ireland, Romania and the UK[2] having done so. The parliamentary assembly of the Council of Europe called on states to repeal criminal sanctions for libel in 2007, as did both the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and UN special rapporteurs on freedom of expression.[3] Criminal defamation laws chill free speech by making it possible for journalists to face jail or a criminal record (which will have a direct impact on their future careers), in connection with their work. Many EU member states have tougher sanctions for criminal libel against politicians than ordinary citizens, even though the European Court of Human Rights ruled in Lingens v. Austria (1986) that:

“The limits of acceptable criticism are accordingly wider as regards a politician as such than as regards a private individual.”

Of particular concern is the fact that insult laws remain in place in many EU member states and are enforced – particularly in Poland, Spain, and Greece – even though convictions are regularly overturned by the European Court of Human Rights. Insult to national symbols is also criminalised in Austria, Germany and Poland. Austria has the EU’s strictest laws in this regard, with the penal code criminalising the disparagement of the state and its symbols[4] if malicious insult is perceived by a broad section of the republic. This section of the code also covers the flag and the federal anthem of the state. In November 2013, Spain’s parliament passed draft legislation permitting fines of up to €30,000 for “insulting” the country’s flag. The Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights, Nils Muiznieks, criticised the proposals stating they were of “serious concern”.

There is a wide variance in the application of civil defamation laws across the EU – with significant differences in defences, costs and damages. Excessive costs and damages in civil defamation and privacy actions is known to chill free expression, as authors fear ruinous litigation, as recognised by the European Court of Human Rights in MGM vs UK.[5] In 2008, Oxford University found huge variants in the costs of defamation actions across the EU, from around €600 (constituting both claimants’ and defendants’ costs) in Cyprus and Bulgaria to in excess of €1,000,000 in Ireland and the UK. Defences for defendants vary widely too: truth as a defence is commonplace across the EU but a stand-alone public interest defence is more limited.

Italy and Germany’s codes provide for responsible journalism defences instead of using a general public interest defence. In contrast, the UK recently introduced a public interest defence that covers journalists, as well as all organisations or individuals that undertake public interest publications, including academics, NGOs, consumer protection groups and bloggers. The burden of proof is primarily on the claimant in many European jurisdictions including Germany, Italy and France, whereas in the UK and Ireland, the burden is more significantly on the defendant, who is required to prove they have not libelled the claimant.

Privacy

Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights protects the right to a private life throughout the European Union. [6] The right to freedom of expression and the right to a private right are often complementary rights, in particular in the online sphere. Privacy law is, on the whole, left to EU member states to decide. In a number of EU member states, the right to privacy can restrict the right to freedom of expression because there are limited protections for those who breach the right to privacy for reasons of public interest.

The media’s willingness to report and comment on aspects of people’s private lives, in particular where there is a legitimate public interest, has raised questions over the boundaries of what is public and what is private. In many EU member states, the media’s right to freedom of expression has been overly compromised by the lack of a serious public interest defence in privacy law. This is most clearly illustrated by the fact that some European Union member states offer protection for the private lives of politicians and the powerful, even when publication is in the public interest, in particular in France, Italy and Germany. In Italy, former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi used the country’s privacy laws to successfully sue the publisher of Italian magazine Oggi for breach of privacy after the magazine published photographs of the premier at parties where escort girls were allegedly in attendance. Publisher Pino Belleri received a suspended five-month sentence and a €10,000 fine. The set of photographs proved that the premier had used Italian state aircraft for his own private purposes, in breach of the law. Even though there was a clear public interest, the Italian Public Prosecutor’s Office brought charges. In Slovakia, courts also have a narrow interpretation of the public interest defence with regard to privacy. In February 2012, a District Court in Bratislava prohibited the distribution or publication of a book alleging corrupt links between Slovak politicians and the Penta financial group. One of the partners at Penta filed for a preliminary injunction to ban the publication for breach of privacy. It took three months for the decision to be overruled by a higher court and for the book to be published.

The European Court of Human Rights rejected former Federation Internationale de l’Automobile president Max Mosley’s attempt to force newspapers to give prior notification in instances where they may breach an individual’s right to a private life, noting that the requirement for prior notification would likely chill political and public interest matters. Yet prior notification and/or consent is currently a requirement in three EU member states: Latvia, Lithuania and Poland.

Other countries have clear public interest defences. The Swedish Personal Data Act (PDA), or personuppgiftslagen (PUL), was enacted in 1998 and provides strong protections for freedom of expression by stating that in cases where there is a conflict between personal data privacy and freedom of the press or freedom of expression, the latter will prevail. The Supreme Court of Sweden backed this principle in 2001 in a case where a website was sued for breach of privacy after it highlighted criticisms of Swedish bank officials.

When it comes to data retention, the European Union demonstrates clear competency. As noted in Index’s policy paper “Is the EU heading in the right direction on digital freedom?“, published in June 2013, the EU is currently debating data protection reforms that would strengthen existing privacy principles set out in 1995, as well as harmonise individual member states’ laws. The proposed EU General Data Protection Regulation, currently being debated by the European Parliament, aims to give users greater control of their personal data and hold companies more accountable when they access data. But the “right to be forgotten” clause of the proposed regulation has been the subject of controversy as it would allow internet users to remove content posted to social networks in the past. This limited right is not expected to require search engines to stop linking to articles, nor would it require news outlets to remove articles users found offensive from their sites. The Center for Democracy and Technology referred to the impact of these proposals as placing “unreasonable burdens” that could chill expression by leading to fewer online platforms for unrestricted speech. These concerns, among others, should be taken into consideration at the EU level. In the data protection debate, freedom of expression should not be compromised to enact stricter privacy policies.

This article was posted on Jan 2 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[1] Article 208 of the Criminal Code.

[2] Article 168(2) of the Criminal Code.

[3] Article 248 of the Criminal Code prohibits ‘disparagement of the State and its symbols, ibid, International PEN.

[4] Index on Censorship, ‘UK government abolishes seditious libel and criminal defamation’ (13 July 2009)

[5] More recent jurisprudence includes: Lopes Gomes da Silva v Portugal (2000); Oberschlick v Austria (no 2) (1997) and Schwabe v Austria (1992) which all cover the limits for legitimate criticism of politicians.

[6] Privacy is also protected by the Charter of Fundamental Rights through Article 7 (‘Respect for private and family life’) and Article 8 (‘Protection of personal data’).