Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Recent developments in a libel trial involving Uzebkistan’s first family have raised concerns about the EU’s involvement with the Karimov family. The claim was brought by President Karimov’s daughter, Lola, against French website Rue89 after one reporter branded her father a “dictator”. Documents produced in court last week, which were originally intended to establish the credibility of the family, have raised questions about why the EU was communicating with Lola Karimov-Tillyaeva about the allocation of $3.7m worth of charitable funding.

The British press loves to hate high court judge Sir David Eady for his judgments in privacy cases. He talks to Joshua Rozenberg about balancing rights

The British press loves to hate high court judge Sir David Eady for his judgments in privacy cases. He talks to Joshua Rozenberg about balancing rights

Where should we draw the line between personal privacy and freedom of expression? In England and Wales, such questions are left to the judges to decide. Parliament has chosen not to create a privacy law; no doubt because politicians of all parties have no wish to antagonise the media any more than is necessary. Even if there were legislation, it could not define all the subtle variants that occur in the real world. So it will always be up to judges to balance Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which requires respect for a person’s private and family life, against Article 10, which protects freedom of expression.

That’s certainly the view of Sir David Eady, and he should know. As the senior high court judge responsible for privacy and defamation work until recently and still a part of the specialist judicial team, Mr Justice Eady has decided several of the leading cases in this rapidly developing area of the law. Perhaps the best known of these is the claim that Max Mosley brought against the publishers of the News of the World, of which more anon.

Speaking to me over tea and cakes at the Royal Courts of Justice in London, Eady recalls that when Labour came to power in 1997 it had always intended the judges to develop a law of privacy. All that was needed was for the human rights convention to be incorporated into the domestic legal systems of the United Kingdom. Under the Human Rights Act 1998, which took effect in 2000, courts are required to “take into account” decisions of the human rights court in Strasbourg when interpreting the convention.

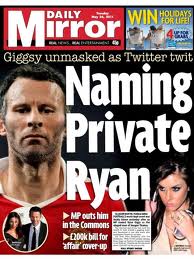

“It’s clear from Strasbourg jurisprudence that anything sexual — anything concerned with personal relationships — attracts protection under Article 8,” Eady says. “And that’s normally the subject matter we’re concerned with, because the press is normally interested in footballers, sex and so on. The big question comes when you have to balance Article 8 against Article 10.”

As a rule, he explains, courts must apply the test in the Princess Caroline case, von Hannover v Germany, decided by the human rights court in 2004: the decisive factor is whether the publication contributes to “a debate of general interest to society”. If the case is about a footballer having a fling, the answer is almost certainly that it doesn’t.

One case in which Eady did have to strike a balance was Lord Browne of Madingley v Associated Newspapers, decided in 2007. The then chief executive of BP tried to stop his former partner from speaking to the Mail on Sunday about their four-year homosexual relationship. Browne resigned from BP immediately after the court of appeal disclosed that he had lied in court about the circumstances in which the two had met.

“Some of the subject-matter of the case was private,” says Eady. “Some engaged the public interest or the interests of shareholders.” And so the media was permitted to report certain aspects of the case. “But in most cases, public interest is not even argued, particularly at the preliminary stage. And there haven’t been many trials.”

If there is a balance to be struck — perhaps because a claimant has forfeited his right to privacy — then the law demands what judges have described as an “intense focus” on the comparative importance of the rights being claimed. There may be room for debate over whether a relationship is already in the public domain: is the relationship known, for example, only to those in an individual’s workplace or more widely? It may be necessary to keep the claimant’s identity private to protect the privacy of his lover or his children. Perhaps an innocent party’s mental health might be jeopardised by disclosure. And circumstances may have changed between the granting of an injunction and the time the case comes to trial.

Privacy law by the back door?

“It’s not a precise art and you can’t legislate for a precise outcome,” Eady says. It’s inherent in a balancing exercise that different judges may reach different conclusions on whether the same couple are conducting their relationship in public or in private. You might say they have appeared together on so many occasions or at so many parties or public functions that this is no longer a private matter. But another judge might say: ‘Well, I think they’ve been fairly discreet about it’.”

“It’s not a precise art and you can’t legislate for a precise outcome,” Eady says. It’s inherent in a balancing exercise that different judges may reach different conclusions on whether the same couple are conducting their relationship in public or in private. You might say they have appeared together on so many occasions or at so many parties or public functions that this is no longer a private matter. But another judge might say: ‘Well, I think they’ve been fairly discreet about it’.”

But he insists that judges do not decide privacy cases on the basis of their religious views or some moral code. What they’re focusing on is the principles laid down in previous cases — in particular, the Strasbourg jurisprudence. If so much depends on a single judge’s intense focus on the case, then perhaps we should pay more attention to the individual judges themselves. There was some concern that Eady, as the judge in charge of the Queen’s Bench jury list until recently, was hearing too many privacy cases himself.

He points out that because privacy is derived from the law of confidence, which evolved as an equitable remedy, many privacy claims are brought in the Chancery division of the High Court — where Eady himself does not sit. The most recent example of this involves allegations of phone-tapping by the News of the World, a case being tried by Mr Justice Vos. Other important privacy issues are dealt with in the Family division.

But Eady acknowledges his own involvement in developing privacy law. “It so happened that I was judge in charge of the list for several years and the practice was in those days that I never did anything else but the Queen’s Bench list.” Although it’s a large division, most of its judges are assigned to other work — criminal trials and appeals, for example, or judicial review — and so it was inevitable that a high proportion of the privacy cases would come before Eady.

Mr Justice Tugendhat, who succeeded Eady as judge in charge of the jury list, is doing a broader range of work. But media cases generally — not just privacy claims — still tend to come before the specialist judges if they are available: Tugendhat, Eady and now Mrs Justice Sharp. “There’s an increasing tendency towards specialisation among the judiciary and the ‘customers’ like to get in front of a specialist judge if they can,” Eady explains. “That tends to be the fashion of the day.”

Can litigants actually choose their judge? “They make a request. And if it’s a reasonable request then the listing office tries to co-operate.” What’s not acceptable is to ask for a case not to be listed before a particular judge for no good reason.

Eady seems resigned to the fact that his decisions are going to be misunderstood and misreported in the press. In complicated cases, he may write a short summary of his decision for the benefit of reporters. But he would not wish to see judges or their communications office justifying decisions by way of a press release. He accepts that ill-informed media comment is something that goes with the territory. “I think it’s inevitable because the press are interested in the press’s own affairs. So privacy and libel get much more coverage than personal injury, commercial cases or even public law, all of which are just as important if not more important.

“There are lots of judgments that have been criticised where it’s quite apparent that people haven’t read them. But there’s nothing you can do about that: the press office aren’t going to give them a spoonful of sugar to make it easier. And if they want to criticise the judgment, they will – whatever it says. But I don’t really bother to read that stuff.”

He thinks again. “I couldn’t miss the Dacre stuff, obviously,” he adds, referring to a speech made by the editor of the Daily Mail to the Society of Editors conference in 2008. Paul Dacre had asserted that “while London boasts scores of eminent judges, one man is given a virtual monopoly of all cases against the media enabling him to bring in a privacy law by the back door”. There had been more of the same criticism subsequently, Eady recalls. “Essentially, the problem is that it misunderstands the function of a judge. It’s presuming that a judge has some kind of political or personal agenda when all that he or she is doing is applying or interpreting the law, rightly or wrongly.”

Surely, judges are human and they are bound to be influenced by their personal views?

“Judges are human and they make mistakes,” Eady replies. “But I think they make a pretty good fist at not being influenced by personal, political or religious views. So if you are saying that somebody should have their privacy maintained in relation to a certain type of lawful but unconventional conduct, that doesn’t mean you go along with it or behave in that way yourself — or necessarily approve of it or have a view about it. If it’s lawful conduct between consenting adults, that’s it: it doesn’t matter what your own personal views or inclinations may be.”

Mosley, privacy, the public interest — how things might have been different

Eady is clearly referring to the Max Mosley case, which he decided in 2008. At that time, Mosley was head of motor-sport’s governing body, the FIA. He established that the News of the World had breached his privacy by revealing that he enjoyed sado-masochistic sex sessions.

But the £60,000 damages Eady awarded Mosley was little consolation for the FIA boss. What Mosley would have preferred was a permanent injunction that prevented details of his sexual preferences from being revealed in the first place. Since he had kept them private, that application would almost certainly have been granted. But there was no application for such an order because Mosley had no idea that the News of the World was about to invade his privacy. The newspaper was not required to warn him in advance and it deliberately withheld the story from the edition that was available on the night before publication.

That’s the gap in the law that Mosley tried to fill. He asked the European Court of Human Rights to rule that the lack of any requirement to notify a potential claimant before writing about his private life amounted to a breach of Article 8. In May 2011, his claim was dismissed, partly because of the “chilling effect” that it would have had. But how significant would it be if Mosley had won and publishers had been required to warn people before writing about their private lives?

“I’m not sure it would be terribly significant”, Eady says, “because there are not that many cases where a newspaper is able to keep it that secret. I genuinely don’t have a personal view on whether it should or shouldn’t happen but I can understand why Mosley is so keen about it.”

Surely it would have an impact on the media? Every time we wanted to disclose personal information about an individual, we would have to give the person concerned an opportunity to seek a court order blocking publication.

An injunction is by no means automatic, Eady insists, although the claimant stands a good chance of being granted an order for a few days, pending a full hearing. But the sort of case we are talking about is not one where the claimant would rush off to court without notifying the defendant newspaper. Since the publisher would have alerted the claimant in the first place, there is no reason why the newspaper should not be represented at the initial court hearing. And if there was a public interest in publication — because, to take a hypothetical example, the mental capacity of a judge, a minister or a surgeon was affected by an undisclosed brain tumour — then an injunction would be refused.

Sex and health are clearly areas that the law will protect in the absence of any over-riding public interest in disclosure. So are personal financial affairs. But what about other areas that an individual in a responsible position may wish to keep private, such as extreme political or religious views? Would the law prevent such views from being made public by a spouse?

“That’s quite a difficult question to answer,” Eady admits. There may be no evidence that the individual’s private views had ever affected the holder’s public position. “On the other hand, you might say that it’s difficult to envisage how somebody who holds those views can be rational.”

Because the French burqa ban happens to be in the news on the day I am interviewing Eady, we discuss what would happen in the case of a strict Muslim who might not let his wife appear in public unless she wears a full veil.

“Does that necessarily mean that the person shouldn’t be allowed to be a judge, or a teacher or whatever it might be? To what extent has he allowed those views to intrude on his decisions or conduct? It all depends on the circumstances.”

At some point, he continues, an individual’s views may become so irrational that his judgment cannot be trusted on anything. “I’d have considerable doubts about a flat-earther being a teacher, or a judge or a doctor.”

So would it have made any difference if there had been a Nazi element to Mosley’s sado-masochistic activities?

“It might have done,” he admits. “I didn”t have to grapple with that in the end because I found that there wasn’t. But if he had been mocking Holocaust victims — which was one of the allegations made in the News of the World — there would have been quite a powerful argument for saying that should have been revealed. He had, at that time, a role in the FIA, which involved dealing impartially with people of all creeds, races, colours and so on.”

It would, of course, have been possible for Mosley to have brought a libel action over the article, which was headlined “F1 Boss has Sick Nazi Orgy with 5 Hookers”. If the newspaper had sought to justify its allegation that there was a Nazi element to Mosley’s role-play, that defence would have been dismissed by Eady on the facts that emerged at the privacy hearing.

“There is a close comparison between privacy and libel,” Eady tells me. “They interlink because they’re both part of the human personality — or, as they tend to call it in Strasbourg, human integrity. So one can see why Article 8 would have them both under its umbrella — although originally, of course, it didn’t. It’s a very recent development that libel has been brought in under Article 8 – not in the convention, obviously, but in case law.”

The frenzy of superinjunctions

And that poses problems. In English law, the same set of facts may give rise to claims in either privacy or libel. A claimant may then choose how to proceed. Much may depend on whether he is seeking an interlocutory injunction — one that prevents publication pending a full hearing.

And that poses problems. In English law, the same set of facts may give rise to claims in either privacy or libel. A claimant may then choose how to proceed. Much may depend on whether he is seeking an interlocutory injunction — one that prevents publication pending a full hearing.

In libel, all that a defendant need do to resist such an injunction is to say he will prove that what he published was true — a test that goes back 120 years to the case of Bonnard v Perryman. “That’s not an answer in privacy, obviously,” explains Eady. “The issue is not, ‘Is it true?’ but ‘Is it your business?'”

In deciding whether to grant an injunction in a privacy case, the court must consider whether the claimant is likely to succeed when the case comes to trial. “It’s a much easier burden for a claimant to discharge in a privacy case than in a libel case because injunctions in libel cases are almost never granted.” Having said that, Eady mentions a recent exception. In ZAM v CFW, decided in March 2011, the high court granted an injunction on the basis that the claimant could not be fully compensated in damages for the injury to his reputation if the threatened libel — which was held to be clearly false — was published.

“Since Strasbourg now regards both privacy and libel as coming under the Article 8 umbrella, the question arises: is it any longer feasible, or sensible, or justifiable, in principle for having separate tests for interlocutory injunctions, depending on whether it’s privacy or libel?”

Is that as far as it goes — or will we eventually see libel and privacy subsumed into one tort called protection of reputation or protection of personal integrity?

As the law now stands, there would be problems at the damages stage, Eady explains. “One of the things you have got to be careful about is not to give a claimant an award of damages which represents restoration of reputation, so that he or she gets the benefit of suing for libel without having done so.”

At the time we are speaking, there is something of a media frenzy over “super-injunctions” — court orders that ban reports of their own existence, at least temporarily. “The classic example of this is of a threatening blackmailer, which is surprisingly common: I’m dealing with one at the moment and I can think of three or four this year. People who know somebody who’s in the public eye and know something that they think is discreditable see the opportunity for making money. They”re in touch with journalists who are ready to pay it.”

At the time we are speaking, there is something of a media frenzy over “super-injunctions” — court orders that ban reports of their own existence, at least temporarily. “The classic example of this is of a threatening blackmailer, which is surprisingly common: I’m dealing with one at the moment and I can think of three or four this year. People who know somebody who’s in the public eye and know something that they think is discreditable see the opportunity for making money. They”re in touch with journalists who are ready to pay it.”

In those circumstances, the judge is likely to grant an injunction. But what happens if the potential blackmailer hears about it through the media before it is formally served on him? He would not be bound by it. “There is a risk he’ll go to the journalist, clinch the deal and then say, ‘You can’t touch me’.” Eady says those are “classic circumstances” for the grant of a superinjunction.

Once the court order has been served on the blackmailer, there is no reason why its existence should not be reported. Indeed, the judgment Eady is writing appears a few days after we speak. OPQ v BJM and CJM is unusual because Eady granted an order of general effect — “against the world” — banning publication of confidential information about the claimant on a permanent basis.

This is something of an innovation. But it has the same effect as a temporary injunction granted ahead of a full hearing. Under the so-called Spycatcher doctrine, such an order binds everyone who knows about it. But that restriction is thought to lapse once a case settles, as OPQ v BJM is about to do. Hence the need for a universal order — which is perfectly logical once you accept the fundamental principle that people are generally entitled to keep their private lives private.

“It’s surprising how many injunctions do hold and how many are settled on private terms, fairly quickly,” Eady tells me. That includes cases where the press are defendants — “because they recognise, on mature reflection, that there’s no public interest argument and they’re happy to get out of it”. For his part, Eady seems to be in no hurry to get out of a job he clearly enjoys. But those judges who were appointed after February 1995 — including Eady and most of his serving colleagues — must retire when they reach the age of 70. That leaves Eady with less than two years to go. Still, with privacy developing as quickly as it is, it will be fascinating to see how far he can develop the law before he leaves the public stage and tries to regain the personal privacy that has eluded him on the bench.

The interview with Sir David Eady took place on 11 April 2011. Find out more about the summer 2011 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, Privacy is dead! long live privacy.

Joshua Rozenberg is a leading commentator on the law and presents the popular BBC Radio 4 series Law in Action. His books include Privacy and the Press (Oxford University Press)

Richard Wilson asks: Why would a London primary school employ the services of a political lobbying firm — and libel lawyers Carter Ruck?

Richard Wilson asks: Why would a London primary school employ the services of a political lobbying firm — and libel lawyers Carter Ruck?

(more…)

A US-based billionaire is using English courts to force American online publishers to expose the identity of users. Judith Townend reports

A US-based billionaire is using English courts to force American online publishers to expose the identity of users. Judith Townend reports