Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The dangers of selling “the wrong” kind of book in Libya are many and varied and yet one chain of bookshops is still open for business. Charlotte Bailey speaks to a bookseller in Tripoli”][vc_column_text]

A street in Tripoli. Credit: David Stanley/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”2/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”We started selling books critical of Gaddafi. We published a book about democracy” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Forces loyal to Field Marshall Khalifa Haftar were accused of burning 6,000 books” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80561″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422014535686″][vc_custom_heading text=”Enemies of the people” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422014535686|||”][vc_column_text]June 2014

Writer Matthias Biskupek took part in demonstrations in East Germany as the Berlin Wall came down. He looks back at the attempts to censor books and theatre.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”92001″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/030642208701600510″][vc_custom_heading text=”The media under Gadaffi” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F030642208701600510|||”][vc_column_text]May 1987

An interview with Fadel Al-Messaoudi, who believes the media has been directly controlled by the government since the cultural revolution of 1973.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94326″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228108533267″][vc_custom_heading text=”Censorship and Col Gadaffi” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228108533267|||”][vc_column_text]October 1981

Libyan journalist exiled in Spain, F. el-Manssoury, reports on soldiers’ accounts of censorship in Libya from first-hand knowledge of the early President Gaddafi’s regime.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/09/free-to-air/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

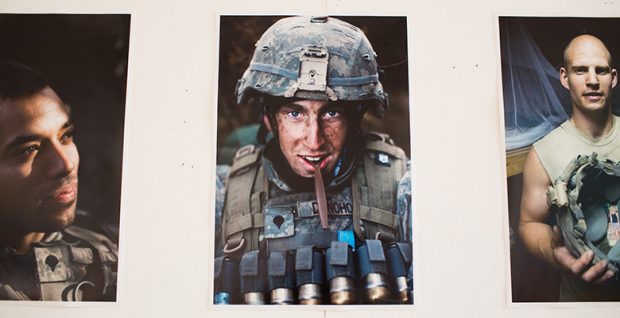

Photo: Liverpool John Moores University

Liverpool John Moores University officially opened its Infidel exhibition, a display of photographs by Tim Hetherington, on Wednesday night. The Liverpool-born photojournalist, who died in Libya under mortar fire in 2011, took the photos during the year he spent embedded with the US Army in Afghanistan’s Korangal Valley while shooting his 2010 Oscar-nominated documentary Restrepo.

Stephen Mayes, a personal friend of Hetherington’s and the director of the Tim Hetherington Trust, spoke at the launch, and highlighted three moments from Hetherington’s short film Diary, which he felt summed up the photographer’s feelings about dividing his time between west London and west Africa. Mayes also recalled a conversation he had with Hetherington around a month before his death, about how photography is great at portraying the “hardware” of war – the guns, the bombs, the carnage – but that Hetherington preferred to work with what he called the “software”, the young men who fight and the people caught in the middle.

The photographs in the Infidel exhibit are a perfect example of what was so impressive about Hetherington’s work. Despite having weathered a year of almost constant combat alongside a platoon of US soldiers, he took striking images that stepped back from the front line. His portraits featured men hugging, relaxing and playing games, highlighting their individual humanity and vulnerability in an environment that treats them as means to an end.

As the new recipient of the Tim Hetherington Fellowship, the result of Index on Censorship’s collaboration with the trust and LJMU (where I graduated in journalism), I’m inspired by the spirit of that work. I’m struck by the bravery and moral fortitude of a man who frequently put himself in harm’s way out of a sense of duty to the people around him. His determination to immerse himself in the lives of his subjects and portray the emotional truth of their experience has reminded me why I always wanted to be a journalist. Journalism is about letting people tell their stories.

Index on Censorship fights for the rights of people to be heard. Hetherington spent his life trying to tell untold stories. It’s an honour to be part of his legacy.

Infidel is open now at the John Lennon Art and Design Building, Duckinfield Street, Liverpool until Friday September 23. Admission is free, 10am to 5pm, Monday to Friday.

Jamal al-Hajji was convicted of defamation on 31 December 2013. (© Amnesty International)

After 42 years of political oppression in Libya, it was hoped that the apparatus of Gaddafi’s regime would be dismantled after he was swept from power. Vestiges of the despot’s suffocating grip on free speech still remain, and are still being used to suppress political expression.

Jamal al-Hajji, a writer and commentator from Tripoli, faces jail and a large fine after comments he made in a television interview in February 2013 sparked a defamation case by government figures. During an interview on al-Wataniya, a Libyan television channel, al-Hajji accused the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mohamed Abulaziz and five other politicians and public figures of conspiring against Libya and the “17 February Revolution”.

Four of them lodged a complaint against al-Hajji, resulting in a court sentencing him to eight months in prison and a 400,000 Libyan dinar fine (around £200,000). His case is being supported by Amnesty International, who say relics from Gaddafi’s punitive legal system are being used to obstruct free speech.

“No one should be sent to prison for expressing their views. Free expression is one of the rights Libyans took to the streets to reclaim during the 2011 uprising against Muammar al-Gaddafi,” said Hassiba Hadj Sahraoui, Deputy Director of the Middle East and North Africa Programme at Amnesty International, in a statement issued on Amnesty’s website.

The charity’s Libya researcher, Magdalena Mughrabi, told Index on Censorship: “The Penal Code which is currently in use is the same as under al-Gaddafi. The Libyan authorities should immediately amend or repeal all laws and articles of the Penal Code which impose arbitrary restrictions on freedom of expression.”

Al-Hajji, now aged 58, was arrested a number of times by the Gaddafi regime — the first time in 2007 for organizing a peaceful gathering to commemorate the deaths of 12 protesters at a 2005 demonstration in Tripoli.

He spent a year in jail without charge, and was then sentenced, by the State Security Court, to twelve years imprisonment. Luckily, he was released a year later and submitted a formal complaint to the authorities, criticising the justice system, maltreatment of prisoners, and the torture and arbitrary detention of Libyan citizens.

The authorities summoned him for questioning over the document and threw him in prison for a further four months.

In 2011, he was arrested once more by police officers, who accused him of hitting a man in his car. At the time he was advocating online for peaceful protests mirroring those which had been happening in Tunisia, Egypt and other states across the Middle East.

And now, even with a new transitional regime in place, al-Hajji has found himself in prison again.

When asked if he thought the revolution had been successful, al-Hajji told Index on Censorship: “It is still going on and will continue, it will not stop until we have freedom. The military are not ready to lead this country so we will fight to remove them until we get a proper, working democracy.”

“I wouldn’t call this a new regime, these people aren’t responsible enough to run a country and in any case, many are from the old Gaddafi regime. They don’t want the laws changed because they know any new laws could be used against them.”

The law used to convict al-Hajj was Article 439 of the Libyan Penal Code, which carries a punishment of up to two years in prison as well as a fine. Several other articles of this Code prescribe prison terms for activities that would commonly be understood as freedom of expression and freedom of association. In cases where someone criticises public officials or state institutions, the recommended punishment can be the death penalty.

The same laws were used in September 2013 to charge Moad al-Hnesh, a Libyan engineer aged 34, who had campaigned against Western intervention into Libya in 2011. While living in the UK, he participated in a Stop the War Coalition demonstration outside the House of Commons in London, during which he was photographed holding a photo of a purported victim of a NATO bombing.

Following his return to Libya, he was arrested on 3rd April 2012 by a militia from Zawiya, after a group of Libyan students who had met him at Coventry University lodged a complaint against him with the Zawiya Military Council. He now faces a life sentence for criticising Libya while abroad, or a reduced sentence of fifteen years for “publically insulting the Libyan people.”

Amara Abdalla al-Khattabi, a journalist aged 67, was arrested in December 2012, a month after his newspaper had published the names of 84 allegedly corrupt judges. He was charged with “insulting constitutional or popular authorities” and also faces up to 15 years in prison. Article 195 of the Penal code was frequently used in the al-Gaddafi era to repress freedom of expression.

Al-Hajji is currently on bail and has an appeal hearing scheduled for 13th February.

This article was posted on 27 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

A pro-democracy protest in Bahrain, where activists have been jailed for inciting protests through their online activities (Photo: Moh’d Saeed / Demotix)

One hundred and forty characters are all it takes.

Twitter users from Marrakech to Manama know—call for political reforms, joke about a sensitive topic, or expose government abuse and you could end up in jail. Following the overthrow of Muammar Qaddafi and Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, authorities in Libya and Tunisia unblocked hundreds of websites and dismantled the state surveillance apparatus. But overall, internet freedom in the region has only declined in the three years since the Arab Spring as authoritarian leaders continue to crack down on any and all threats to their ever-tenuous legitimacy.

As the online world has become a fundamental part of Arab and Iranian societies, leaders are waking up to the “dangers” of social media and placing new restrictions on what can be read or posted online. This shift has been most marked in Bahrain, one of the most digitally-connected countries in the world. After a grassroots opposition group took to the streets to demand democratic reforms, authorities detained dozens of users for Twitter and Facebook posts deemed sympathetic to the cause. Similarly, several prominent activists were jailed on charges of inciting protests, belonging to a terrorist organization, or plotting to overthrow the government through their online activities.

Conditions in Egypt—where social media played a fundamental role in mobilising protesters and documenting police brutality—continued to decline over the past year. In only the first six months of Mohammad Morsi’s term, more citizens were prosecuted for “insulting the office of the president” than under Hosni Mubarak’s entire 30-year reign. Cases have now been brought against the same bloggers and activists that were instrumental in rallying the masses to protest against Mubarak (and later Morsi) in Tahrir Square, while countless others were tortured by Muslim Brotherhood thugs or state security forces.

Even in the moderate kingdoms of Morocco and Jordan, state officials are looking to extend their existing controls over newspapers and TV channels to the sphere of online media. Ali Anouzla, a website editor in Morocco, faces terrorism charges in the latest attempt by the state to silence him and his popular online newspaper, Lakome. Access to independent journalism is even worse in Jordan, where over 200 news sites have been blocked for failing to obtain a press license. The government instituted burdensome requirements in a bid to deter any views that counter the state-sponsored narrative.

If governments are beginning to pay attention, it is because online tools for social mobilisation and individual expression are having a profound impact. Social media accounts were set up for every candidate in Iran’s 2013 presidential elections, despite the fact that Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube are all blocked within the country. In Saudi Arabia – which now boasts the highest Twitter and YouTube usage per capita of any country in the world – social media has been used to promote campaigns for women’s right to drive, to highlight the mistreatment of migrant workers, and to debate sensitive subjects such as child molestation. Citizen journalism was vital in documenting chemical weapons use in Syria, and a new online platform alerts local residents of incoming scud missiles. Nonetheless, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Syria rank as some of the least free countries in the world in terms of internet freedom according to Freedom House’s Freedom on the Net study.

Remarkably, the country that has made the most positive strides over the past three years, was once among the most repressive online environments in the region – Tunisia. Protest videos from the town of Sidi Bouzid led to an intense crackdown on online dissidents by the Ben Ali regime. Digital activists even enlisted the help of Anonymous, the hacktivist group, to rally international media attention, provide digital security tools, and bring down government websites. Since then, Tunisian authorities have ceased internet censorship, reformed the regulatory environment, and ceded control of the state-owned internet backbone. Tunisia is now the only country in the region to have joined intergovernmental group the Freedom Online Coalition.

So while the snowball effect of social media contributed to the overthrow of several despots, many of the region’s internet users conversely find themselves in more restrictive online environments than in January 2011. Authoritarian governments now know exactly what the face of revolution looks like and, over the past three years, have shown their commitment to counter the internet’s potential to empower citizens and mobilise opposition. Users in liberal democracies may joke about the insignificance of “liking” a post on Facebook or uploading a video to YouTube, but in a region where your social media activity can make you an enemy of the state, 140 characters can lead to serious repercussions.

This article was posted on 21 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org