Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

A dangerous religious fanatic, yesterday (Image Demotix/David Mbiyu)

Last weekend, I appeared on the BBC’s The Big Questions, the Sunday morning religion and ethics show that airs at precisely the time Christians should be at church services.

The Big Question I’d been hauled in to address was whether there were any topics that were too sacred for humour – a variation of the old “where do you draw the line?” which has been in the news quite a bit of late, with the Jesus and Mo cartoon controversy (which started with The Big Questions), the attempt in Northern Ireland to ban a Reduced Shakespeare Company play based on the Bible, and the banning of demagogic French comic Dieudonne from the UK.

As it turned out, we barely discussed any of these specific topics, but rather kept to what could now almost be called the traditional touchstones in these conversations: Motoons and The Life Of Brian.

The discussion was disappointingly calm, but I did, I think, manage to get one crucial point across, one I’d been meaning to bring up since discussing the RSC ban in Northern Ireland.

In the context of religion, censorship is increasingly, simply, about control. Specifically, who is in charge of the sacred text.

At the height of the Rushdie Affair, Christopher Hitchens noted that it represented a war between the ironic mind and the literal mind. This was particularly apparent when watching Free Presbyterian preacher David McIlveen discuss the Reduced Shakespeare Company’s abridged Bible spoof. McIlveen could not, and would not understand the idea that his interpretation of a text was not the only one. Speaking on the Nolan show, he repeatedly suggested that the RSC was presenting a false version of the “Word of God”. Of course, to an extent, they were, but McIlveen seemed to confuse interpretation with, well, lying.

I was reminded of this while reading an exchange between Alex Clark and Stephanie Merritt in the Observer last Sunday.

They were discussing JK Rowling’s view that in hindsight, she would not have had Hermione and Ron, two characters from her Harry Potter series, ending up romantically entangled. Merritt and Clark debated interestingly on authorship and ownership, particularly in the age of fan fiction.

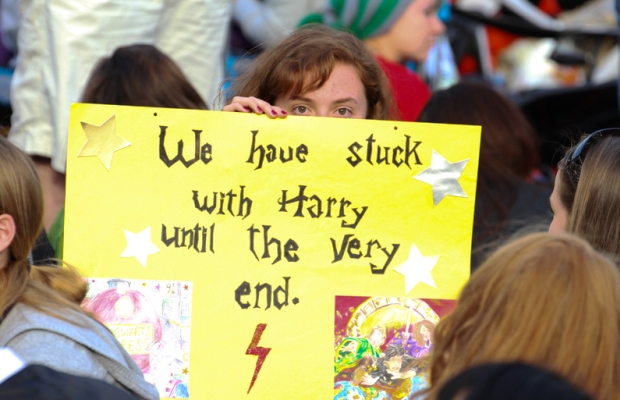

A lot of people are very emotionally attached to the Harry Potter stories, and no doubt some were genuinely unhappy with Rowling’s suggestion that well, the sacred text may be wrong after all. Even her position as creator of that particular universe did not leave her immune from criticism. As Merritt – a historical novelist whose own hero is heretic Giordano Bruno – notes: “I can see why fans felt insulted. They’ve made an emotional investment in those characters and in the storyline as it exists.”

It’s unlikely that Rowling will revise the tale of Hermione and Ron’s romance, but, considering it’s quite possible that at some point, Potterism will become a religion (if grown adults are playing Quidditch, we’re probably half way there), then it’s worrying that Rowling has already introduced a potential point of schism. Do you believe in the true text? Do Ron and Hermione belong together? Or do you believe what the great transcriber of Potterism, Ro-Ling said, that they weren’t suited and maybe split after a fling. Should Hermione even have ended up with Harry?

This could be worse than anything Northern Ireland has seen.

This article was published on 11 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Councillors in Glasgow have lifted an unofficial 30-year-old ban on the Monty Python film The Life of Brian. The council’s licensing and regulatory committee approved a request on Tuesday from Glasgow Film Theatre to show the biblical satire under a 15 certificate. Read more here