Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Freedom of Expression Awards 2016 from Index on Censorship on Vimeo.

A female journalist training reporters from within war-torn Syria, and a group busting online censorship in China are among this year’s Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards winners.

The winners, announced on Wednesday evening at a gala ceremony in London, also included a Yemen-based street artist and campaigners from Pakistan battling internet clampdowns.

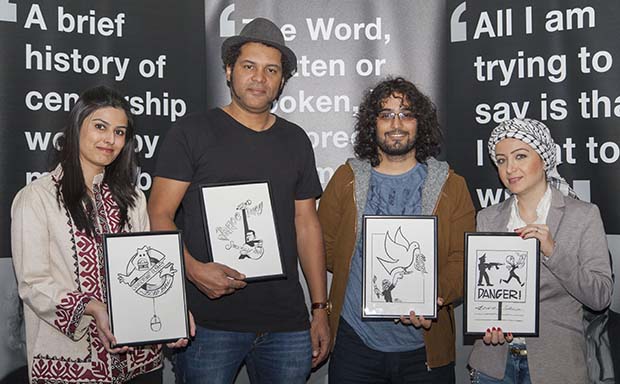

Awards are presented in four categories: arts, journalism, digital activism and campaigning. The winners were: Yemeni street artist Murad Subay (arts), Syrian journalist Zaina Erhaim (journalism), transparency advocates and circumventors of China’s “Great Firewall” GreatFire (digital activism) and the women-led digital rights campaigning group Bolo Bhi (campaigning).

“These winners are free speech heroes who deserve global recognition,” said Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg. “They, like all of those nominated, face huge personal and political hurdles in their fight to ensure that others can express themselves freely.”

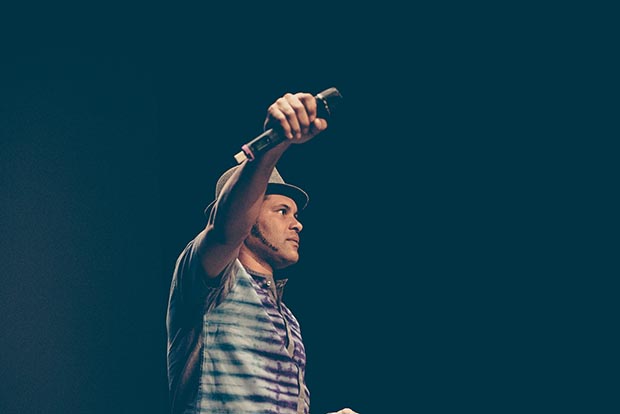

Drawn from a shortlist of 20, and more than 400 initial nominations, the winners were presented with their awards at a ceremony at The Unicorn Theatre, London, hosted by comedian Shazia Mirza. Music was provided by Serge Bambara – aka “Smockey” – a musician from Burkina Faso who won the inaugural Music in Exile Fellowship, presented in conjunction with the makers of award-winning documentary They Will Have to Kill Us First: Malian Music in Exile. The award was presented by Martyn Ware, founder member of the Human League and Heaven 17.

#IndexAwards2016: Shazia Mirza, Farieha Aziz, Murad Subay, Jake Hanrahan, Zaina Erhaim, Nadia Latif, Jodie Ginsberg, Bindi Karia, Anthony House, James Rhodes, Martyn Ware, Kirsty Brimelow, Ziyad Marar (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Actors, writers and musicians were among those celebrating with the winners. The guest list included actor Simon Callow, academic Kunle Olulode, and journalists Lindsey Hilsum, Matthew Parris and David Aaronovitch.

Winners were presented with a framed caricature of themselves created by Malaysian cartoonist Zulkiflee Anwar Haque (“Zunar”), who faces 43 years in jail on sedition charges for his cartoons lampooning the country’s prime minister and his wife.

Each of the award winners becomes part of the second cohort of Freedom of Expression Awards fellows. They join last year’s winners – Safa Al Ahmad (Journalism), Rafael Marques de Morais (Journalism), Amran Abdundi (Campaigning), Tamás Bodoky (Digital activism), Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat (Arts) – as part of a world-class network of campaigners, activists and artists sharing best practices on tackling censorship threats internationally.

Through the fellowship, Index works with the winners – both during an intensive week in London and the rest of the awarding year – to provide longer term, structured support. The goal is to help winners maximise their impact, broaden their support and ensure they can continue to excel at fighting free expression threats on the ground.

Judges included human rights barrister Kirsty Brimelow QC; Bahraini campaigner Nabeel Rajab, a former Index award winner; pianist James Rhodes, whose own memoir was nearly banned last year; Nobel prize-winning author Wole Soyinka; tech entrepreneur Bindi Karia; and journalist Maria Teresa Ronderos, director of the Open Society Foundation’s independent journalism programme.

Ziyad Marar, global publishing director of Sage Publications, said: “Through working with Index for many years both as publisher of the magazine and sponsors of the awards ceremony, we at Sage are proud to support a truly outstanding organisation as they defend free expression around the world. Our warmest congratulations to everyone recognised tonight for their achievements and the inspiring example they set for us all.”

This is the 16th year of the Freedom of Expression Awards. Former winners include activist Malala Yousafzai, cartoonist Ali Ferzat, journalists Anna Politkovskaya and Fergal Keane, and human rights organisation Bahrain Center for Human Rights.

Winners of the 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards: from left, Farieha Aziz of Bolo Bhi (campaigning), Serge Bambara — aka “Smockey” (Music in Exile), Murad Subay (arts), Zaina Erhaim (journalism). GreatFire (digital activism), not pictured, is an anonymous collective. (Photo: Sean Gallagher for Index on Censorship)

2016 Freedom of Expression Awards: The acceptance speeches

Bolo Bhi: “What’s important is the process, and that we keep at it”

Zaina Erhaim: “I want to give this award to the Syrians who are being terrorised”

GreatFire: “Technology has been used to censor online speech — and to circumvent this censorship”

Murad Subay: “I dedicate this award today to the unknown people who struggle to survive”

Smockey: “The people in Europe don’t know what the governments in Africa do.”

2016 Freedom of Expression Journalism Award winner Zaina Erhaim (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Zulkiflee Anwar Haque, aka “Zunar”, upper right, is saluted by the audience. (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Google’s Anthony House and tech entrepreneur Bindi Karia presented the 2016 Freedom of Expression Digital Activism Award to anonymous tech collective GreatFire (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

2016 Freedom of Expression Journalism Award winner Zaina Erhaim and Jake Hanrahan of Vice News (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Sage’s Ziyad Marar, Fareiah Aziz, director of the 2016 Freedom of Expression Campaigning Award Bolo Bhi and human rights barrister at Doughty Street Chambers London Kirsty Brimelow (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Theatre director Nadia Latif, 2016 Freedom of Expression Arts Award Murad Subay and pianist James Rhodes (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Music in Exile Fellowship Winner Serge Bambara, aka Smockey (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Music in Exile Fellowship Winner Serge Bambara, aka Smockey (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Music in Exile Fellowship Winner Serge Bambara, aka Smockey (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Musician Martyn Ware, founder of The Human League and Heaven 17 (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Pianist James Rhodes and 2016 Freedom of Expression Arts Award winner Murad Subay (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Farieha Aziz, director of 2016 Freedom of Expression Campaigning Award winner Bolo Bhi (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

2016 Freedom of Expression Journalism Award winner Zaina Erhaim (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian and 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards host Shazia Mirza (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

The 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards gala (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

When a repressive regime falls, there is a glorious moment when people are able to tell their stories for the first time. I was lucky enough to hit that moment last year when researching my book Sandstorm; Libya in the Time of Revolution.

When a repressive regime falls, there is a glorious moment when people are able to tell their stories for the first time. I was lucky enough to hit that moment last year when researching my book Sandstorm; Libya in the Time of Revolution.

For 42 years, Colonel Gaddafi’s Libya was pretty much closed to the outside world. Journalists got in occasionally, usually to interview the Brother Leader, but Libyans were banned from talking to foreigners. Media within the country were state controlled and severely restricted. So when Gaddafi was swept from power, Libyans were desperate to talk. In the Tripoli souk I came across 64 year old Mohammed Mustafa Saudi, crafting copper crescent moons to go on minarets. He told me how he loved Gaddafi when he came to power in 1969, but changed his mind in the 1970s when he saw people hanging from gibbets in the street, and when he was press-ganged into the army for 11 years. “All my life journalists have been asking me questions, because I’m the first guy you meet when you come into the metal-workers’ souk,” he said. “But I’ve never been able to tell my story before.” When I sat in the hotel lobby, people who had heard I was writing a book came up to ask if their stories could be included. “Do you want to hear my story of how MI6 and the CIA collaborated in my ‘extraordinary rendition’ back to Libya?” asked Sami al Saadi, one of two men who is suing the British government for delivering him into the hands of Gaddafi’s torturers.

Of course not everyone feels free. The dark-skinned Tawerga people, who fought for Gaddafi during the seige of the port of Misrata, have been driven from their village and now live in miserable camps. The Misrata brigades burnt down their homes, and they dare not rebuild not for fear of being merely silenced but of being killed. They talked to me, but only in the camp — there was no question of returning home. Many dark-skinned Libyans are accused by the militia who spear-headed the revolution of being mercenaries who fought for Gaddafi. Some have been detained and tortured, others are in hiding.

Yet this is nonetheless a time when most Libyans are talking as never before. Dozens of new newspapers and TV channels have started up. Some are the vanity projects of rich men, others are suspected of being a way of “image laundering”, enabling people who worked with Gaddafi to proclaim new, revolutionary credentials. Yet the fact that they are out there provides hope that freedom of speech may take hold in the new Libya.

In Sandstorm I quote a line from WH Auden: “They wept and quarrelled; freedom was so wild.” I think about that a lot. In Libya today they quarrel about everything — what kind of government they should have, the rules for political parties, whether the first elections can be held in June or not. It’s chaotic and dangerous. But it’s also glorious, because Libyans are speaking freely for the first time in 42 years.